See Part III to learn about how the Bee Line and other Midwest railroads reset, and sought to accomplish, their goal – to reach St. Louis.

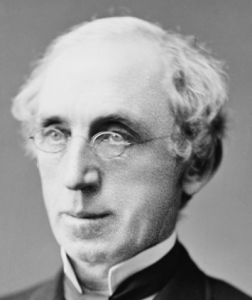

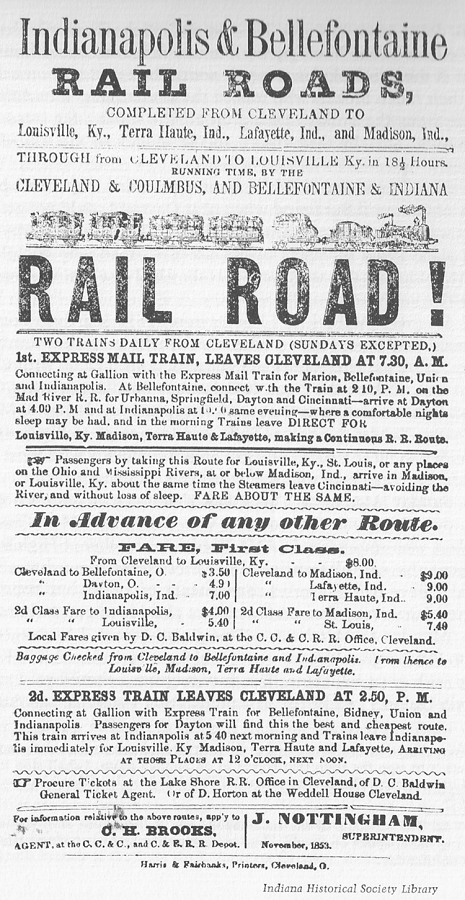

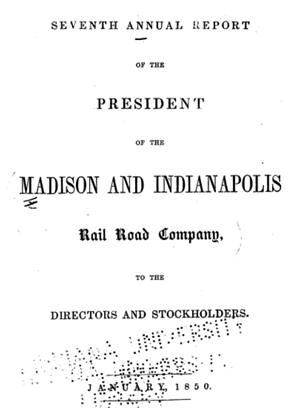

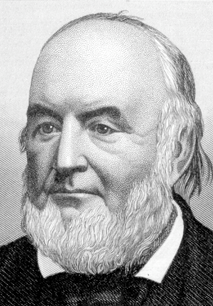

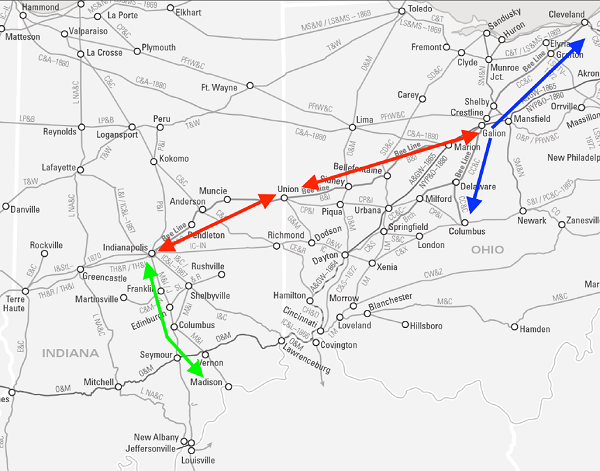

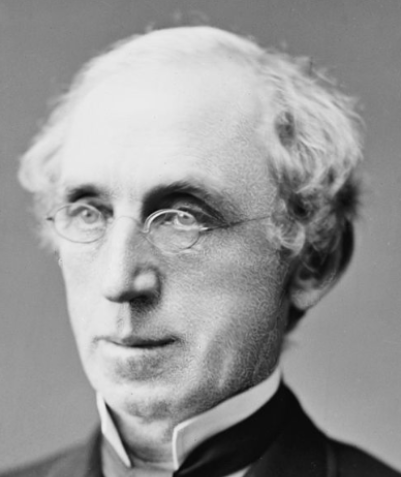

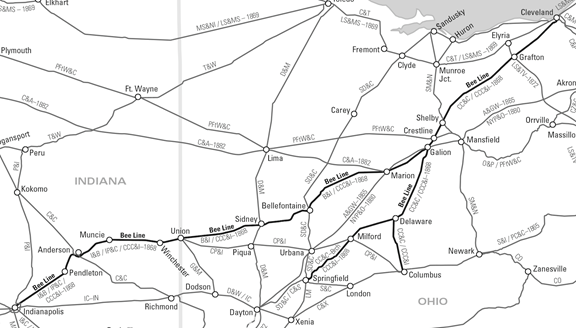

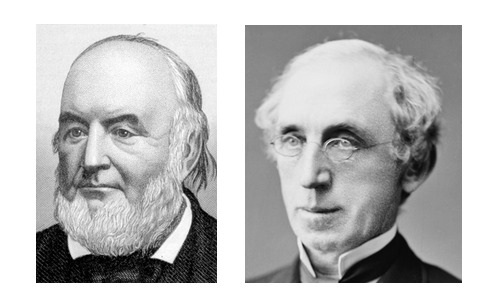

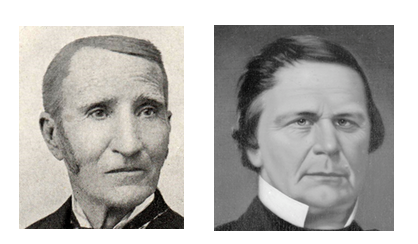

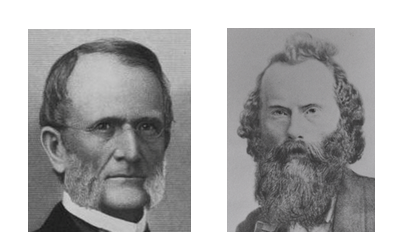

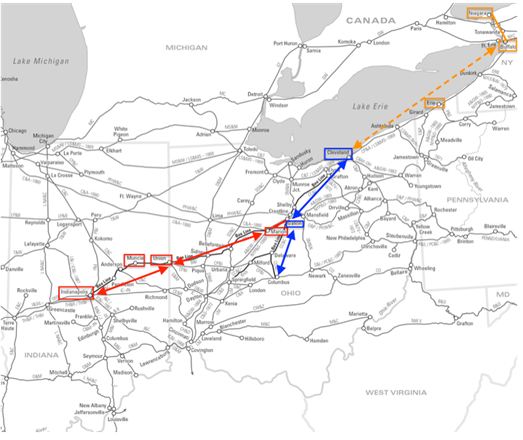

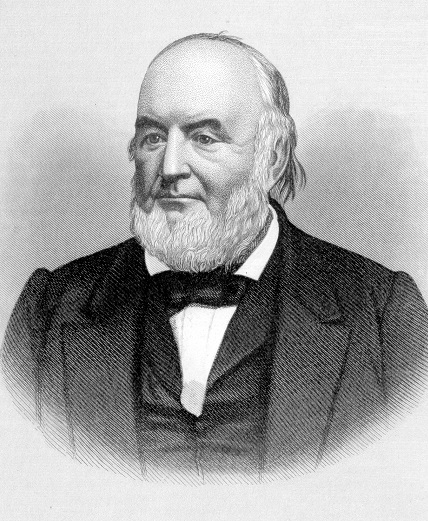

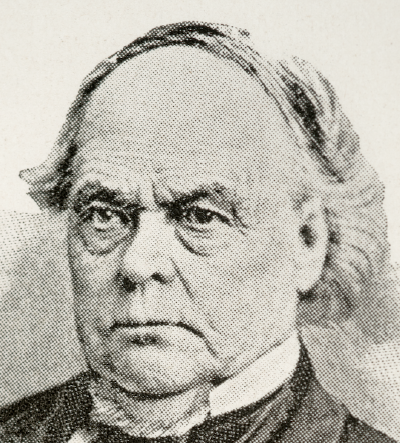

With John Brough’s elevation to the presidency of the Bee Line’s Indianapolis and Bellefontaine Railroad [I&B] segment – between Indianapolis and Union – on June 30, 1853, the Cleveland Clique was understandably euphoric. Brough’s newly arranged presidential authority there and at the Mississippi and Atlantic Railroad [M&A], about to begin construction between Terre Haute and St. Louis, personified the Clique’s growing regional dominance. By all appearances they, through the Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati Railroad (CC&C) and president Henry B. Payne, would soon control the key Midwest rail corridor linking the East Coast and the West.

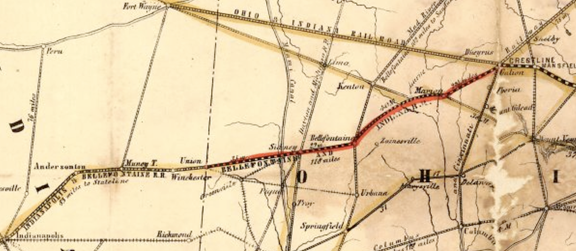

At the same time, the closer-to-home Bellefontaine and Indiana [B&I] – linking the I&B at Union with the Clique’s marquee railway, the CC&C, at Galion OH – had already found itself under the financial sway of the Cleveland band. Incredibly, the strategy to command a string of railroads tying St. Louis to the Eastern truck lines then breaching Ohio’s eastern boundary had been orchestrated by the CC&C’s Henry Payne in little more than two years.

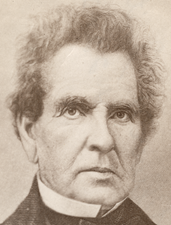

In the almost giddy atmosphere that prevailed following John Brough’s coronation, an impromptu trip was arranged. Why not visit Terre Haute, and the Illinois state line for that matter, and then travel in a single day from Terre Haute to Cleveland? It would underscore what the Clique had accomplished, provide an on-the-ground view of the new western terminus of the coordinated lines, and draw them closer to the independently minded stockholder/management team at the controls of the Terre Haute and Richmond Railroad [TH&R] – the only gap in the Clique’s string of pearls between Cleveland and St. Louis.

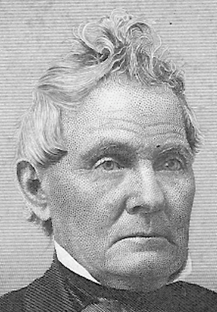

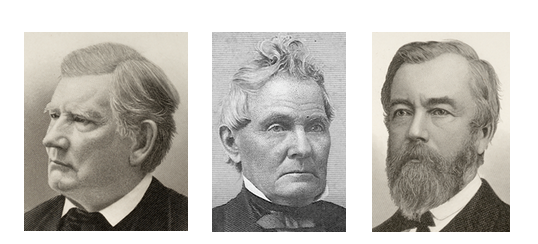

Members of the Cleveland Clique along with president James H. Godman of the B&I, newly minted I&B president John Brough as well as board member Calvin Fletcher and secretary Douglass Maguire boarded a special train destined for Terre Haute on July 1st. It had been less than twenty-four hours since the Clique’s I&B annual meeting coup. None of the original I&B Hoosier board members went along for the ride.

In one respect the trip was a success. They drank brandy and wine with Samuel Crawford, president of the TH&R, supped together and made it to a symbolic bridge spanning the Wabash—peering across wide stretches of western Indiana farmland toward Illinois. Truman P. Handy and William Case, board members of the Cleveland Clique’s cornerstone CC&C railroad, continued on to the Illinois line by horse and returned to Terre Haute by 3 a.m. Now they could boast of having made it from the Illinois line to Cleveland in a single day.

A private train left Terre Haute before dawn on July 2nd. It ran at a blistering thirty miles per hour until hitting a cow near Belleville—knocking the engine and car off the track. It was a near-death experience, as Calvin Fletcher recounted. Still, they were in Indianapolis by 6:30 a.m.

Fletcher did not record whether they accomplished the lofty goal of making it to Cleveland that day, as he remained in Indianapolis. All the same, except for the lack of participation by original I&B board members, it had been a notable start to John Brough’s presidency – and provided a glimpse of the Clique’s mechanism for expansion. The Hoosier Partisan’s absence would prove to be a telling sign of issues looming ahead.

Two weeks later Calvin Fletcher was among a sizable number of Indiana business and political nobility who, along with their spouses, received an invitation from the Cleveland Clique. The request was to join them for an all-paid junket to Niagara Falls. “I had an invitation with our citizens, those of Lafayette, Crawfordsville, Terre Haute, Dayton, Cleveland, Bellefontaine &c…a number have an invitation here.”

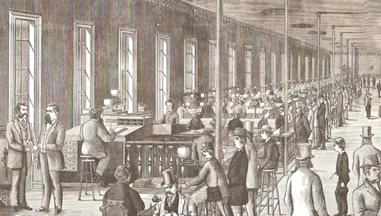

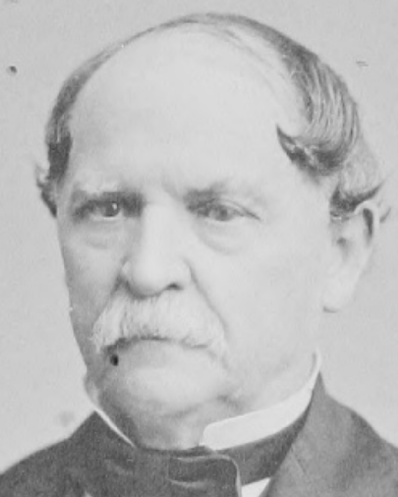

Hoosier Partisans Alfred Harrison, Daniel Yandes and David Kilgore as well as ubiquitous Indiana railroad construction engineer and soon to be I&B board member Thomas A. Morris were among the throng. They all boarded a special train awaiting them in Indianapolis on the morning of July 20th. In his diary, Calvin Fletcher would capture both the spectacle of the excursion and the travails of travel during this era.

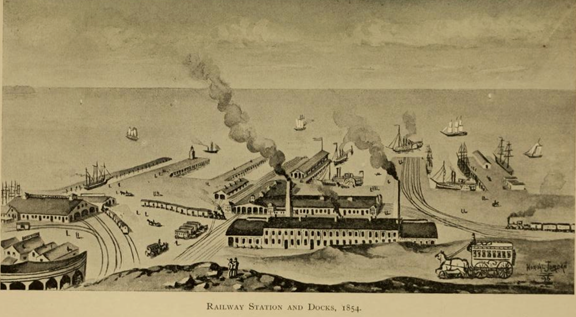

The conductor to Union was none other than Fletcher’s recently hired son Stoughton Jr., who helped the party around a derailed freight train along the way. They arrived at Union about 10:30 a.m. Connection delays added to a tardiness that precluded the Hoosier contingent from stopping at Marion, Ohio, for a B&I board–arranged dinner. Instead, they raced on to Galion to connect with CC&C cars coming from Columbus. The crowd reached Cleveland at 7:30 p.m., only to find the boat hired to take the assembled masses to Buffalo had broken down.

Because the politicians of Erie, Pennsylvania had made smooth rail travel between Cleveland and Buffalo nearly impossible during the early 1850s, going by this route was not a viable option. To force passengers and freight to overnight in Erie, city fathers had mandated different track ‘gauges’ (the lateral distance between iron rails) for railways entering/leaving the city from the east and west. The Erie “war of the gauges”, in combination with intentionally and poorly synchronized railroad schedules, wreaked havoc on passengers and shippers alike. Erie thrived on this senselessness until 1855, during which time near-riots by local merchants and warehouse workers nearly scuttled a move to finally synchronize schedules and re-lay rails to a uniform gauge.

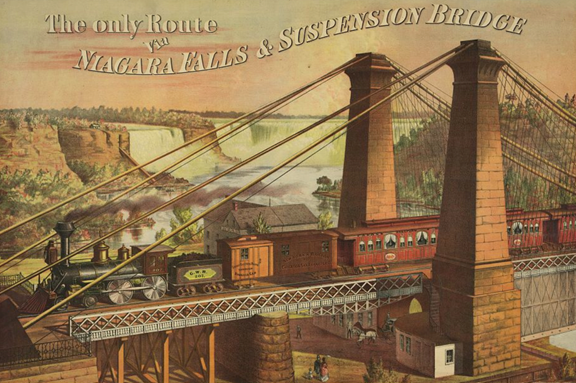

It was midnight before more than 750 passengers stranded in Cleveland boarded a replacement vessel to Buffalo – arriving the next day at noon. There, a train of nearly fifteen cars met the ship and whisked its guests the final miles to Niagara Falls. They took in the falls and were awestruck by the engineering feat of the recently completed railway suspension bridge traversing the Niagara River. The revelers were then ferried behind the tumultuous sheets of water before dinner and a moonlit trip to Goat Island. The excursion lasted less than twenty-four hours. On the return boat trip to Cleveland the assembled guests lunched, ironically, at Erie, Pennsylvania.

That evening Cleveland’s mayor hosted what Fletcher referred to as a “soirée” of dinner, music, and speeches. He called it “a most splendid affair that I ever witnessed.” As might have been expected, newspaper editors and writers had been invited gratis. They clearly earned their passage by publishing effusive articles in the regional and national press.

The editor of the Indianapolis-based Locomotive gushed: “We have never taken an excursion with which we were so well pleased. Every arrangement was made in princely style for the accommodation of the invited guests; and everything free as air, from our railroad bills down to our omnibus bills, including hotels and everything necessary.” It had proved to be the most incredible public relations feat of its day.

Finally, on the return leg from Cleveland to Indianapolis, the B&I board hosted the earlier-deferred dinner party at Marion, Ohio. Toasts were exchanged, a “three cheers” shouted, and the Hoosiers were off to Union the next morning. There they waited an hour for connecting passengers coming from Cincinnati. Exhausted, the entourage supped at Muncie and finally arrived back in Indianapolis by 11 p.m.

Still, for the people of the era, it had been both an awe-inspiring event and a technological marvel. To the parochial Hoosier Partisans, it brought home the sobering reality that the Cleveland Clique outgunned them financially and politically. The sheer number of interconnected board, business, banking, and government relationships represented at the Cleveland festivities was astounding. And they had gathered with a single purpose: to focus their wide-ranging powers on dominating the Midwest rail corridor between Cleveland and St. Louis.

The I&B, basking in the afterglow of this landmark event, which drew investor attention to its pivotal role as a funnel for traffic from Ohio to Indianapolis, saw its stock and bond prices jump. Nonetheless, Calvin Fletcher decided to sell all but $5,000 of his stock in August. He found a ready market: “I distributed among my friends who seemed to want it & one demanded, as a matter of right as I had offered to others, that he should have a portion. The stock soon fell & it was fortunate I let it go.”

Fletcher’s unemotional view was sprinkled with a candid and ominous reality, however: “Brough the president has failed to establish his right to go through to St. Louis straight. This I think will effect [sic] the road materially.” And he was right.

Whatever the reason for the I&B’s price bounce, it did not reflect the financial or business reality with which John Brough and the Cleveland Clique were faced. Brough’s usefulness to the Cleveland Clique appeared, for the moment, to be in question.

Check back for Part V to learn more about how the Cleveland Clique turned their attention to binding the various component parts of the Bee Line together both physically and legally – to the irritation of the Hoosier Partisans.

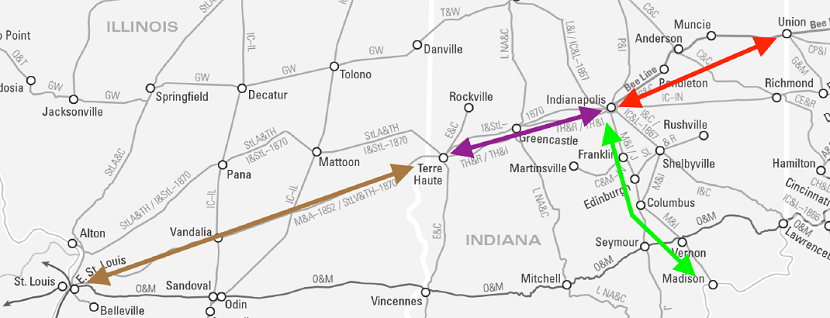

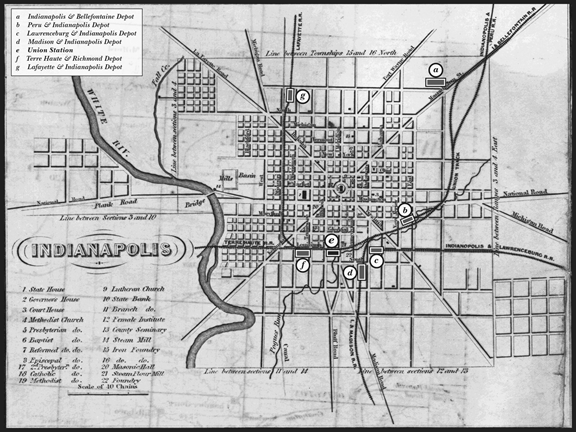

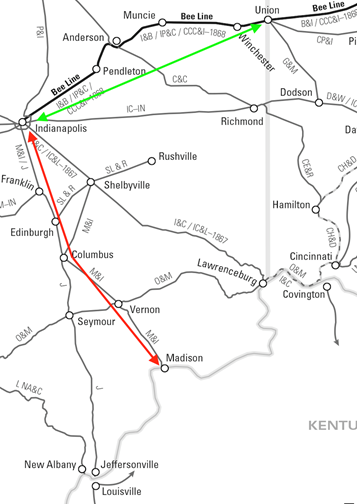

![Midwest Railroads Map, circa 1860, showing the Madison and Indianapolis [M&I], Terre Haute and Richmond [TH&R], and component roads of the Bee Line: Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati [CC&C]; Bellefontaine and Indiana [B&I]; Indianapolis and Bellefontaine](http://blog.history.in.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Midwest-Railroads-Map-c1860.png)

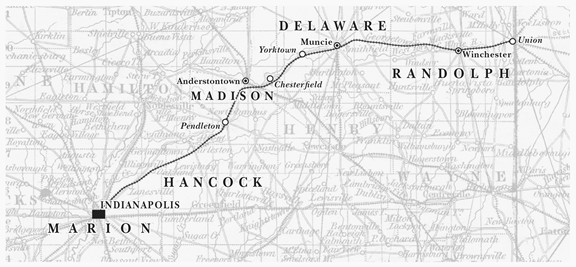

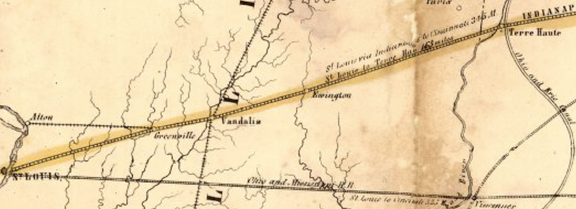

![Railroads west from Indiana, including the Terre Haute and Richmond [TH&R], Ohio and Mississippi [O&M], Mississippi and Atlantic [M&A], and St. Louis, Alton and Terre Haute [StLA&TH]](http://blog.history.in.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Railroads-West.png)

![image of The Madison and Indianapolis Railroad [M&I] and involved roads: the Peru and Indianapolis Railroad [P&I], extending north from Indianapolis, and the Mississippi and Atlantic Railroad [M&A], extending west to St. Louis. Terre Haute and Richmond [TH&R]](http://blog.history.in.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/MI.png)