As a researcher, few things are more disheartening than coming across that blemish on an otherwise inspiring legacy. But it happens more often than not in the messiness of human history. Events and actors often occupy an ambiguous position between right and wrong, progressive and stagnant, heroic and indifferent. We wish the loose ends of the stories could be tied up into one neat moral bow, but often it’s more complex. In wrestling with this phenomenon, I concluded two things: that context is everything and that we must remember that the historical figures we idolize—and sometimes demonize—were, in fact, evolving humans. The visionary and controversial leadership of Indianapolis Rev. Oscar McCulloch and Gary, Indiana Rep. Katie Hall inspired these conclusions.

In the early 20th century, Oscar McCulloch’s misguided attempt to ease societal ills was utilized to strip Americans of their reproductive rights. Born in Fremont, Ohio in 1843, McCulloch studied at the Chicago Theological Seminary before assuming a pastorship at a church in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. He moved to Indianapolis in 1877 to serve as pastor of Plymouth Congregational Church, situated on Monument Circle. On the heels of economic depression triggered by the Panic of 1873, he implemented his Social Gospel mission. He sought to ease financial hardship by applying the biblical principles of generosity and altruism. To the capital city, Brent Ruswick stated in his Indiana Magazine of History article, McCulloch “brought a blend of social and theological liberalism and scientific enthusiasm to his work in Indianapolis.”[1] He also brought a deep sense of empathy for the impoverished and soon coordinated and founded the city’s charitable institutions, like the Indianapolis Benevolent Society, Flower Mission Society, and the Indianapolis Benevolent Society.

In 1878, McCulloch encountered the Ishmael family, living in abject poverty. He described them in his diary [2]:

composed of a man, half-blind, a woman, and two children, the woman’s sister and child, the man’s mother, blind, all in one room six feet square. . . . When found they had no coal, no food. Dirty, filthy because of no fire, no soap, no towels.

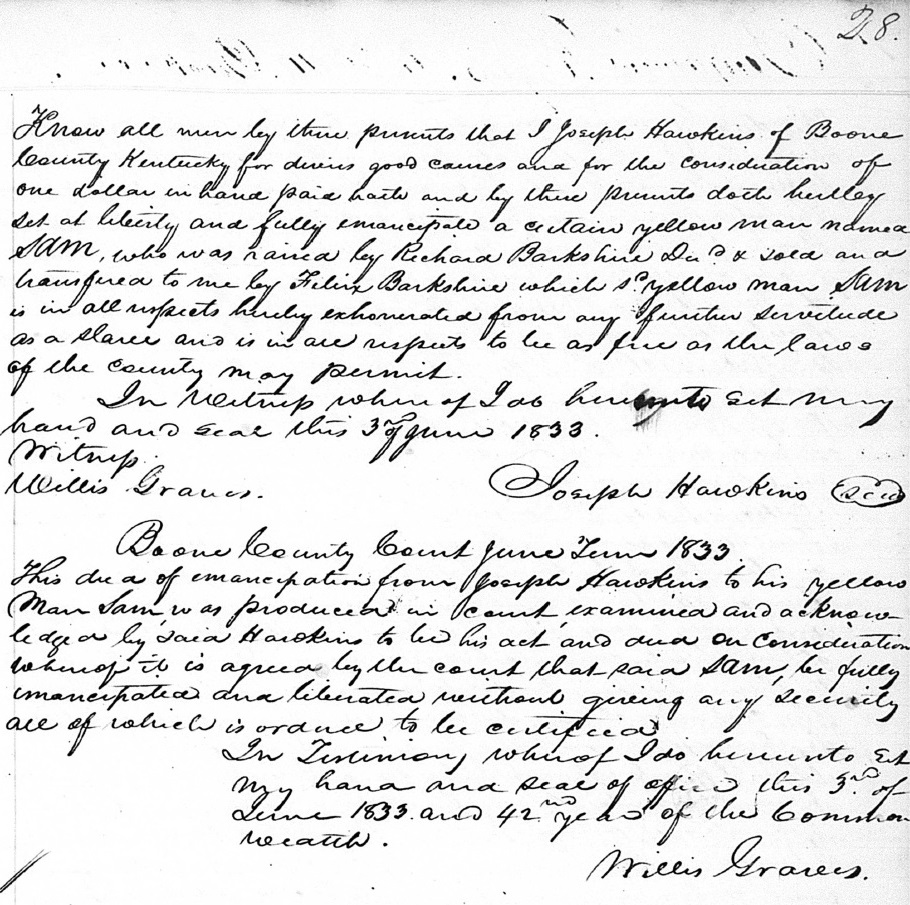

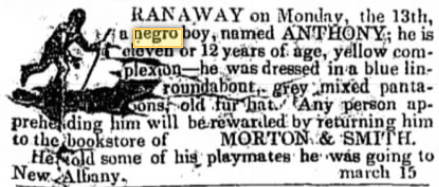

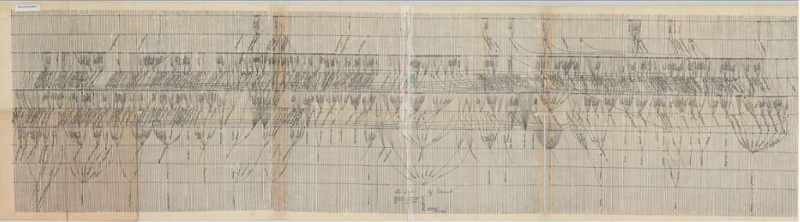

Disturbed by the encounter, McCulloch headed to the township trustee’s office to research the Indianapolis family, who lived on land known as “Dumptown” along the White River, as well as in predominantly African American areas like Indiana Avenue, Possum Hollow, Bucktown, and Sleigho.[3] He discovered that generations of Ishmaels had depended upon public relief. According to Ruswick, McCulloch came to believe that the Ishmaels, “suffering from the full gamut of social dysfunctions,” were not “worthy people suffering ordinary poverty but paupers living wanton and debased lives.”[4] Over the course of ten years, the pastor sought to discover why pauperism reoccurred generationally, examining 1,789 ancestors of the Ishmaels, beginning with their 1840 arrival in Indiana.

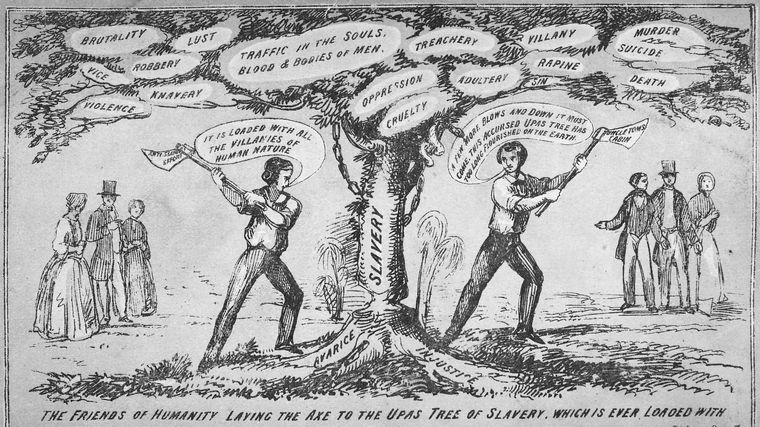

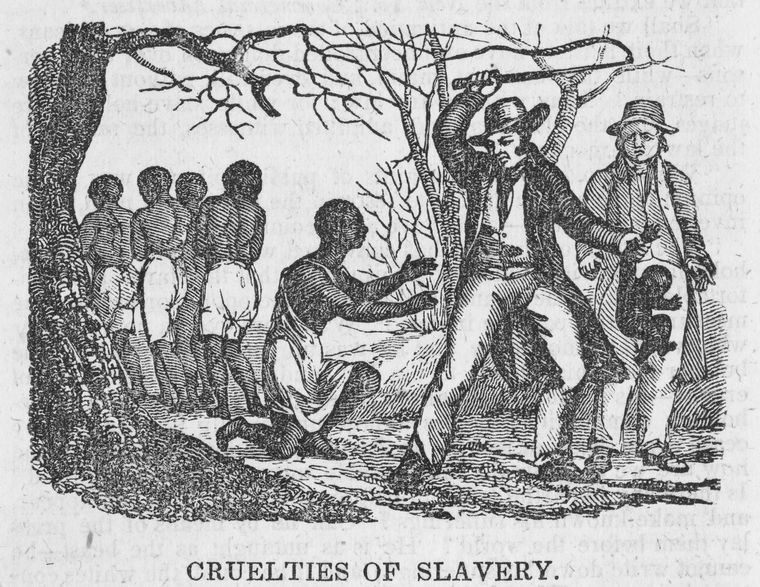

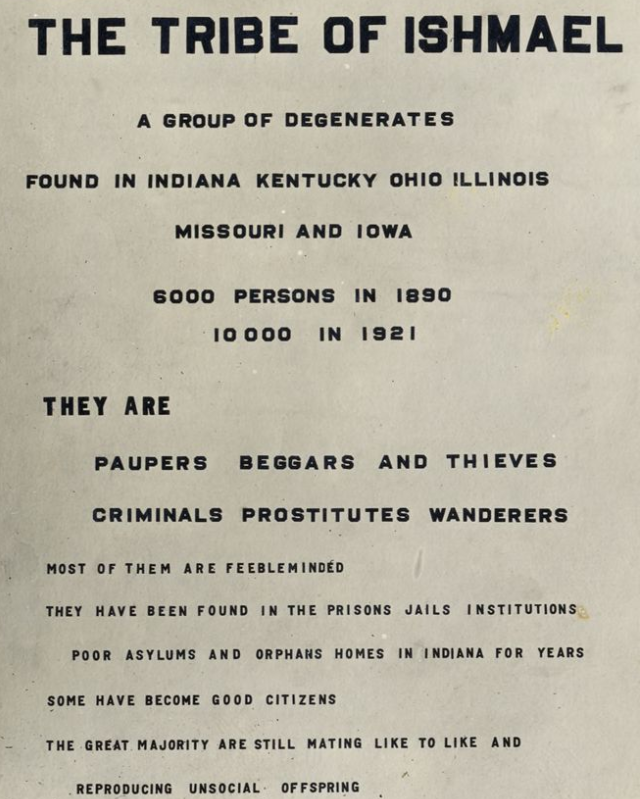

The blemish. McCulloch’s nationally renowned 1888 “Tribe of Ishmael: A Study in Social Degradation” concluded that heredity and environment were responsible for social dependence.[5] He noted that the Ishmaels “so intermarried with others as to form a pauper ganglion of several hundreds,” that they were comprised of “murderers, a large number of illegitimacies and of prostitutes. They are generally diseased. The children die young.” In order to survive, the Ishmaels stole, begged, “gypsied” East and West, and relied on aid from almshouses, the Woman’s Reformatory, House of Refuge and the township. Assistance, he reasoned, only encouraged paupers like the Ishmaels to remain idle, to wander, and to propagate “similarly disposed children.” In fact, those benevolent souls who gave to “begging children and women with baskets,” he alleged, had a “vast sin to answer for.” McCulloch’s sentiment echoes modern arguments about who is entitled to public assistance.

In addition to revoking aid, McCulloch believed the drain on private and public resources in future generations could be stymied by removing biologically-doomed children from the environment of poverty. Ruswick noted that McCulloch, in the era of Darwin’s Natural Selection, believed “pauperism was so strongly rooted in a person’s biology that it could not be cured, once activated” and that charities should work to prevent paupers from either having or raising children. This line of thought foreshadowed Indiana’s late-1890s sterilization efforts and 1907 Eugenics Law. The Charity Organization Society, consulting McCulloch‘s “scientific proof,” decided to remove children from families with a history of pauperism and vagrancy, essentially trampling on human rights for the perceived good of society.

But McCulloch had a change of heart. He began to rethink the causes of poverty, believing environmental and social factors were to blame rather than biological determinism. Ruswick notes that “Witnessing the rise of labor unrest in the mid-1880s, both within Indianapolis and nationwide, McCulloch began to issue calls for economic and social justice for all poor.”* To the ire of many of his Indianapolis congregants, the pastor defended union demonstrations and pro-labor parties. He no longer traced poverty to DNA, but to an unjust socioeconomic system that locked generations in hardship. McCulloch believed that these hardships could be reversed through legislative reform and organized protest. To his dismay, McCulloch’s new ideology reportedly resulted in his church being “‘broken up.'”

In a nearly complete reversal of his stance on pauperism, McCulloch wrote a statement titled “The True Spirit of Charity Organization” in 1891, just prior to his death. He opined [6]:

I see no terrible army of pauperism, but a sorrowful crowd of men, women and children. I propose to speak of the spirit of charity organization. It is not a war against anybody. . . . It is the spirit of love entertaining this world with the eye of pity and the voice of hope. . . . It is, then, simply a question of organization, of the best method for method for the restoration of every one.

But after McCulloch’s death, Arthur H. Estabrook, a biologist at the Carnegie Institution’s Eugenics Research Office, repurposed McCulloch’s social study (notably lacking scientific methodology) into the scientific basis for eugenics. Historian Elsa F. Kramer wrote that Estabrook revised McCulloch’s “casual observations of individual feeblemindedness” into support for reforms that “included the institutionalization of adult vagrants, the prevention of any possibility of their future reproduction, and the segregation of their existing children—all to protect the integrity of well-born society’s germ-plasm.”[7] McCulloch had unwittingly provided a basis for preventing those with “inferior” genetics from having children in the name of improving the human race. Kramer notes that co-opting the Ishmael studies for this purpose reflected “the changing social context in which the notes were written.”[8] In fact, Estabrook resumed the Ishmael studies in 1915 because “of their perceived value to eugenic arguments on racial integrity.”[9]

McCulloch’s work influenced Charles B. Davenport’s report to the American Breeders Association and Dr. Harry C. Sharp’s “Indiana Plan,” an experimental program that utilized sterilization to curtail unwanted behaviors of imprisoned Indiana men. Sharp also promoted Indiana’s 1907 Eugenics Law, the first in the U.S., which authorized a forced sterilization program “to prevent procreation of confirmed criminals, idiots, imbeciles and rapists” in state institutions. Twelve states enacted similar laws by 1913 and approximately 2,500 Hoosiers were sterilized before the practice ceased in 1974.[10] Even though McCulloch moved away from his problematic beliefs, for decades they were utilized to rob Americans of the ability to have a family. His legacy proved to be out of his hands.

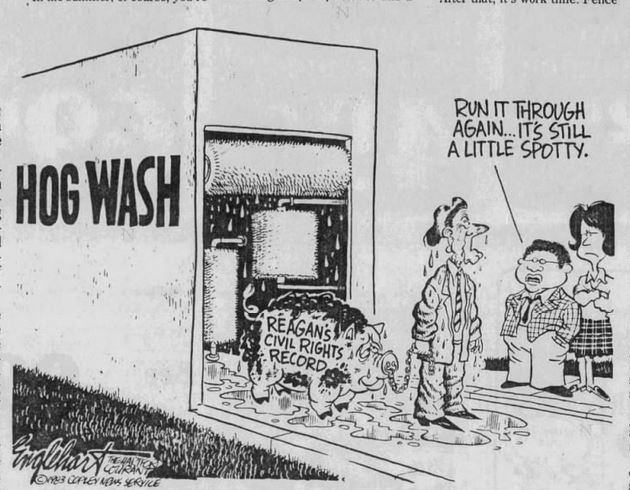

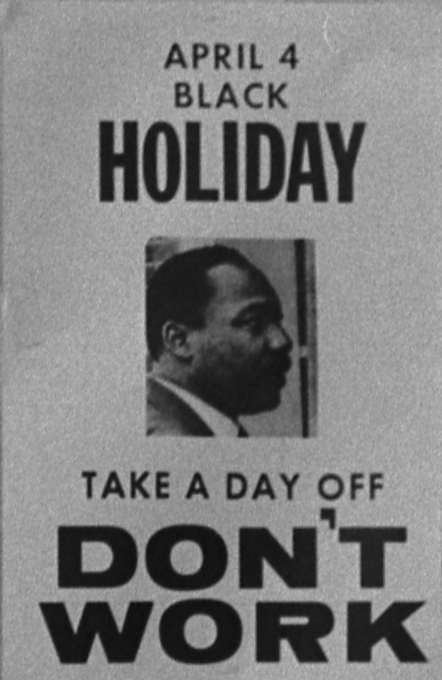

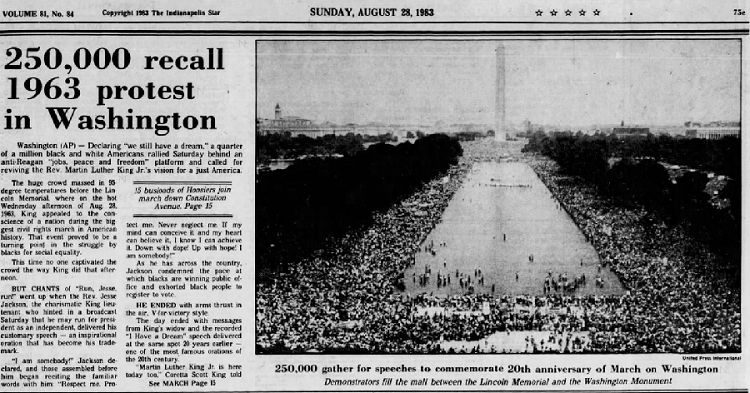

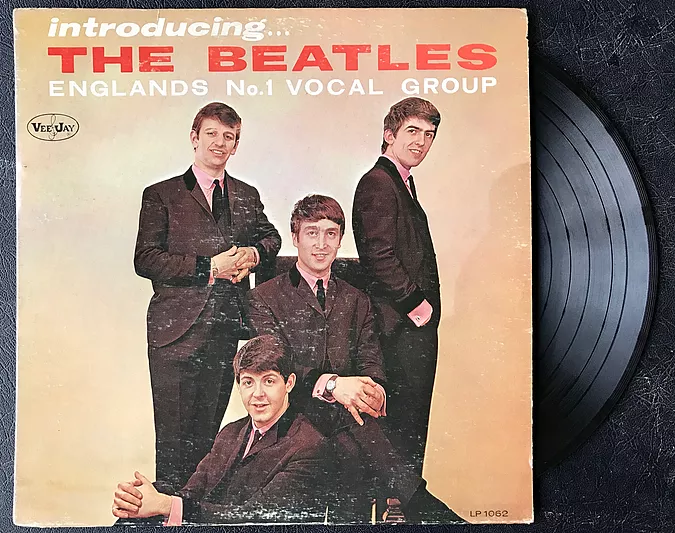

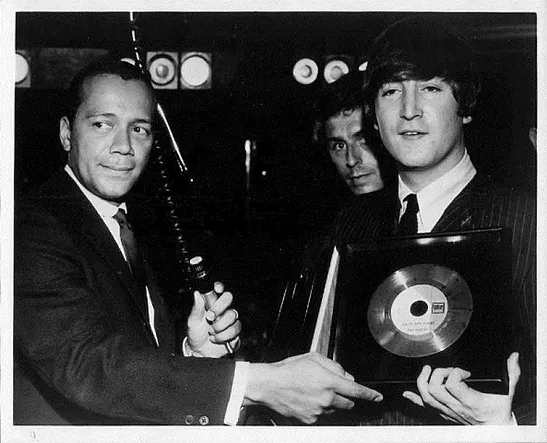

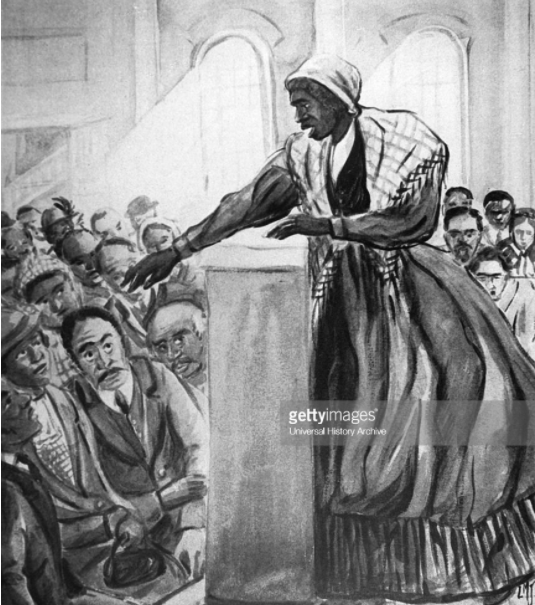

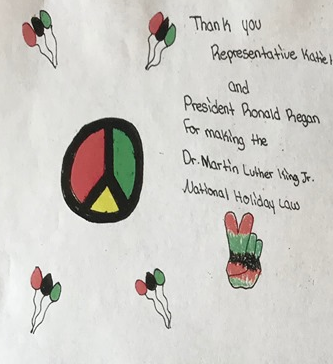

The complexities of African American Rep. Katie Hall’s legacy could not be more different. In 1983, Rep. Hall, built on a years-long struggle to create a federal holiday honoring the civil rights legacy of the late Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on his birthday. Each year since Dr. King’s assassination in 1968, U.S. Representative John Conyers had introduced a bill to make Dr. King’s January 15 birthday a national holiday. Many became involved in the growing push to commemorate Dr. King with a holiday, including musician Stevie Wonder and Coretta Scott King, Dr. King’s widow. But it was the Gary, Indiana leader who spent the summer of 1983 on the phone with legislators to whip votes and successfully led several hearings called to measure Americans’ support of a holiday in memory of King’s legacy. Hall was quoted in the Indianapolis News about her motivation:

‘The time is before us to show what we believe— that justice and equality must continue to prevail, not only as individuals, but as the greatest nation in this world.’

Representative Hall knew the value of the Civil Rights Movement first hand. In 1938, she was born in Mississippi, where Jim Crow laws barred her from voting. Hall moved her family to Gary in 1960, seeking better opportunities. Hall trained as a school teacher at Indiana University, and she taught social studies in Gary public schools. As a politically engaged citizen, Hall campaigned to elect Gary’s first Black Mayor, Richard Hatcher. She broke barriers herself when, in 1974, she became the first Black Hoosier to represent Indiana in Congress. Two years later, she ran for the Indiana Senate and won. While in the Indiana General Assembly, Hall supported education measures, healthcare reform, labor interests, and protections for women, such as sponsoring a measure to “fund emergency hospital treatment for rape victims,” including those who could not afford to pay.

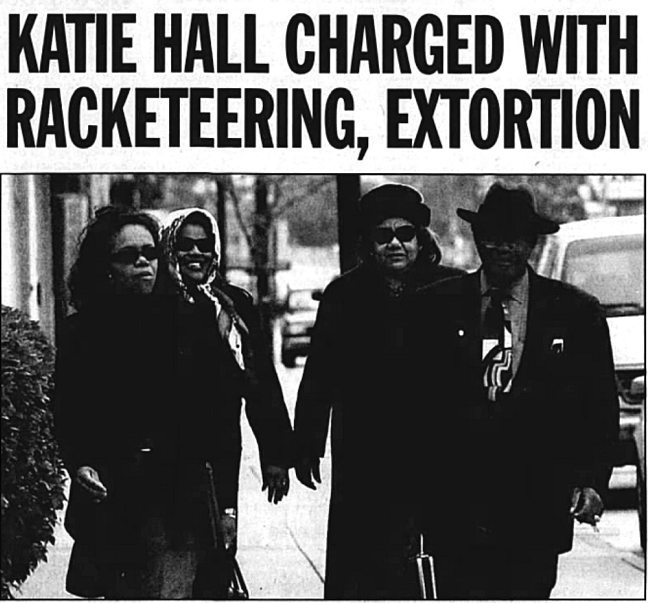

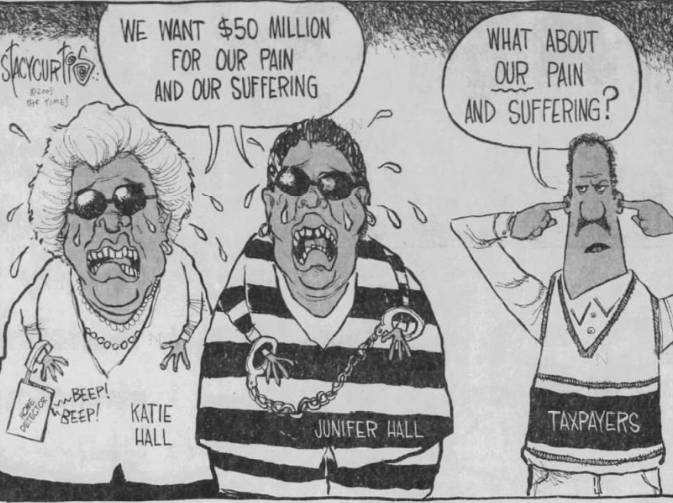

The blemish. In 1987, voters elected Hall Gary city clerk, and it was in this position that her career became mired in scandal. In 2001, suspended city clerk employees alleged that Hall and her daughter and chief deputy, Junifer Hall, pressured them to donate to Katie’s political campaign or face termination. Dionna Drinkard and Charmaine Singleton said they were suspended after not selling tickets at a fundraiser for Hall’s reelection campaign. Although suspended, the Halls continued to list them as active employees, which meant Drinkard was unable to collect unemployment. The U.S. District Court charged the Halls with racketeering and perjury, as well as more than a dozen other charges. At trial, a federal grand jury heard testimony from employees who stated that the Halls forced them to sell candy and staff fundraisers to maintain employment. Allegedly, the Halls added pressure by scheduling fundraisers just before pay day. Investigators discovered cases of ghost-employment, noting that employees listed on the office’s 2002 budget included a former intern who was killed in 1999, a student who worked for the clerk part time one summer two years previously, and Indiana’s Miss Perfect Teen, who was listed as a “maintenance man.”

According to the Munster Times, the Halls alleged their arrest was racially motivated and their lawyers (one of whom was Katie’s husband, John) claimed that “the Halls only did what white politicians have done for decades.” Josie Collins countered in an editorial for the Times that “if they do the crime, they should do the time. This is not an issue of racial discrimination. It is an issue of illegal use of the taxpayers’ money.” Whether or not the Halls’ allegation held water, it is clear from phone recordings between Junifer and an employee, as well as the “parade of employees past and present” who testified against the Halls, that they broke the law.

In 2003, the Halls pled guilty to a federal mail fraud charge that they extorted thousands of dollars from employees. By doing so, their other charges were dropped. They also admitted to providing Katie’s other daughter, Jacqueline, with an income and benefits, despite the fact that she did not actually work for the city clerk. The Halls immediately resigned from office. In 2004, they seemed to resist taking accountability for their criminal actions and filed a countersuit, in which they claimed that Gary Mayor Scott King and the Common Council refused to provide them with a competent lawyer regarding “the office’s operation.” The Munster Times noted “The Halls said they wouldn’t have broken the law if the city of Gary had provided them sound advice.” Instead, they lost their jobs and claimed to suffer from “‘extreme mental stress, anxiety, depression, humiliation and embarrassment by the negative publication of over 500 news articles.'” For this, they asked the court to award them $21 million.

The City of Gary deemed the Halls’ Hail Mary pass “frivolous,” and a “‘form of harassment,'” arguing that “the Halls had no one to blame for their troubles but themselves.” The countersuit was dismissed. Junifer served a 16-month sentence at the Pekin Federal Correctional Institution in Pekin, Illinois. Katie Hall was placed on probation for five years. According to the Munster Times, one observer at her trial noted:

‘We are seeing the destruction of an icon.’

Thus ended Katie Hall’s illustrious political career, in which she worked so hard to break racial barriers and honor the legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. This leads to the perhaps unanswerable question: “Why?” Maybe in the early 2000s no one was immune from being swept into Gary’s notoriously corrupt political system. This system arose from the city’s segregated design, one which afforded white residents significantly more opportunities than Black residents. Possibly, the Halls sought to create their own advantages, at the expense of others. Either way, it is understandable that some Gary residents opposed the installation of a historical marker commemorating her life and work.

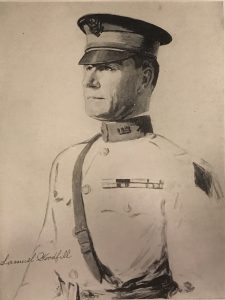

In many ways, McCulloch’s and Hall’s stories are not unique. It seems almost inevitable that with such prolific careers, one will make morally or ethically questionable decisions or at least be accused of doing so. Take African American physician Dr. Joseph Ward, who established a sanitarium in Indianapolis to treat Black patients after being barred from practicing in City Hospital. He forged professional opportunities for aspiring African American nurses in an era when Black women were often relegated to domestic service and manual labor. In 1924, Dr. Ward became the first African American commander of the segregated Veterans Hospital No. 91 at Tuskegee, Alabama. With his appointment, the hospital’s staff was composed entirely of Black personnel. Ward’s decision to accept the position was itself an act of bravery, coming on the heels of hostility from white residents, politicians, and the Ku Klux Klan. The blemish. In 1937, before a Federal grand jury he pled guilty to “conspiracy to defraud the Government through diversion of hospital supplies.” The esteemed leader was dismissed “under a cloud” after over eleven years of service. However, African American newspapers attributed his fall from grace to political and racial factors. According to The New York Age, Black Republicans viewed the “wholesale indictment of the Negro personnel” at Veterans Hospital No. 91 as an attempt by Southern Democrats to replace Black staff with white, to “rob Negroes of lucrative jobs.” Again, context comes into play when making sense of blemishes.

If nothing else, these complex legacies are compelling and tell us something about the period in which the figures lived. Much like our favorite fictional characters—Walter White, Don Draper, Daenerys Targaryen—controversial figures like Katie Hall and Oscar McCulloch captivate us not because they were perfect or aspirational, but because they took risks and were complex, flawed, and impactful. They were human.

*Text italicized by the author.

SOURCES USED:

Katie Hall, Untold Indiana.

Elsa F. Kramer, “Recasting the Tribe of Ishmael: The Role of Indianapolis’s Nineteeth-Century Poor in Twentieth Century Eugenics,” Indiana Magazine of History 104 (March 2008), 54.

Origin of Dr. MLK Day Law historical marker notes.

Brent Ruswick, “The Measure of Worthiness: The Rev. Oscar McCulloch and the Pauper Problem, 1877-1891,” Indiana Magazine of History 104 (March 2008), 9.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Ruswick, 9.

[2] Ibid., 10.

[3] Kramer, 54.

[4] Ruswick, 10.

[5] Oscar C. McCulloch, “The Tribe of Ishmael: A Study in Social Degradation,” (1891), accessed Archive.org.

[6] Quotation from Ruswick, 31.

[7] Kramer, 39.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid., 61.

[10] Learn more about the 1907 Indiana Eugenics Law and Indiana Plan with IHB’s historical marker notes.