There’s no better place to learn about family stories than old newspapers. I learned this lesson as a child when I tagged along with my maternal grandmother, LeNore Hoard Enz. Four families in her line bought land patents in Whitley County before 1840. In her pursuit for more information, Grammy traveled to courthouses for deeds and wills, and libraries for city directories, historical history books, and periodicals. She visited state and local historical societies and centuries-old cemeteries.

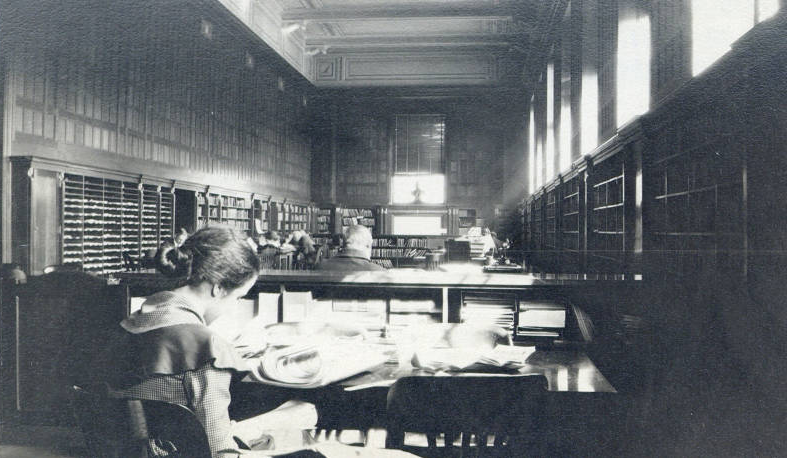

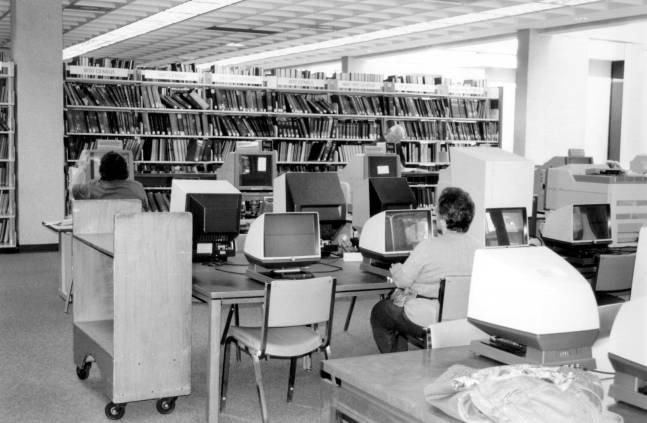

I loved to visit the South Whitley Community Public Library basement. With Grammy’s encouragement, I spent hours reading bound volumes of historical weekly broadsheets. Even at age ten, I knew these old newspapers were important. After retirement, it was my turn to make sense of and preserve the family treasures. Today there are many options to save family history, from Snapfish books to NPR’s Storyworth. Some people, like me, author a book or two about their family, such as Centennial Farm Family: Cultivating Land and Community 1837-1937 and Always Carl: Letters from the Heartland.

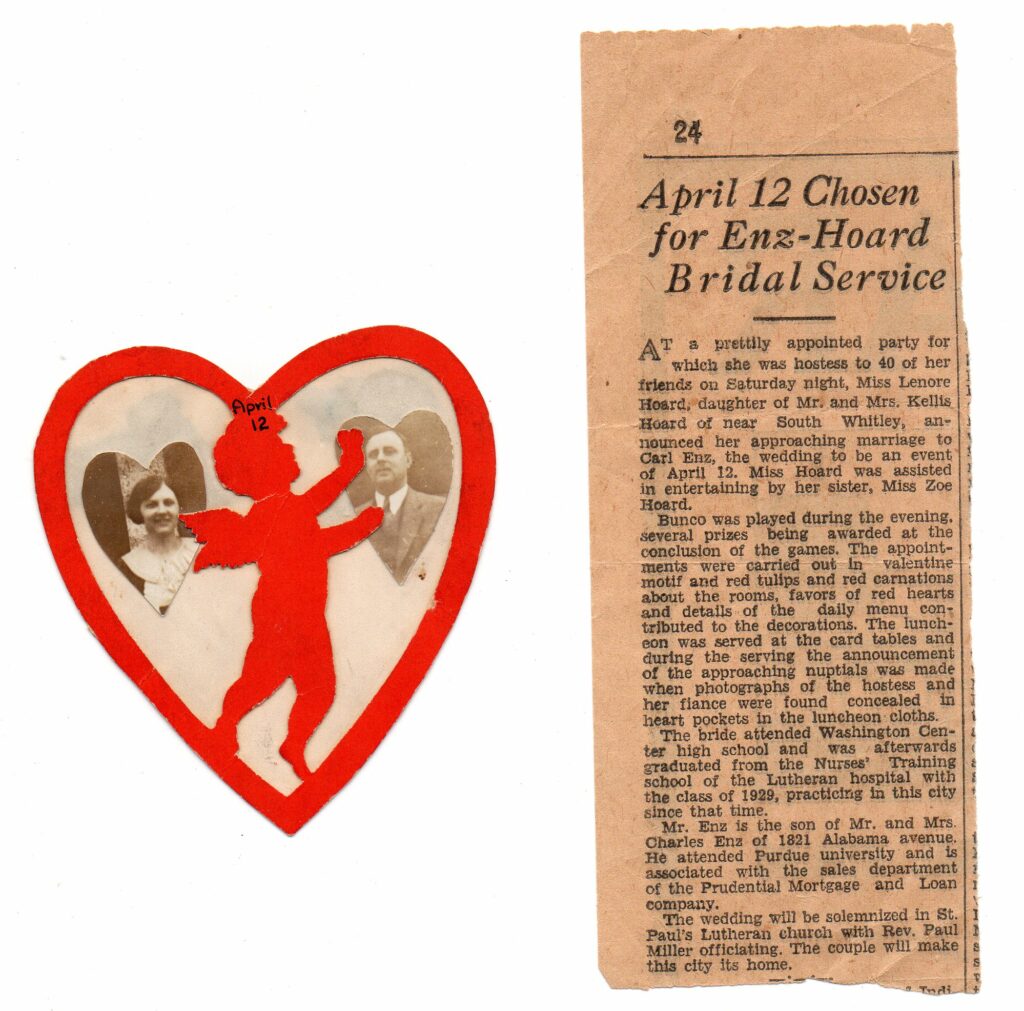

No matter your chosen medium, facts can lack meaning without sensory details or context. I interviewed and kept notes with my grandmother, aunt, and father. But it wasn’t enough for my books, so I turned to historical newspapers. While I had legal documents, letters, pictures, charts, and family treasures, newspaper stories could corroborate or invalidate my research. Historical newspapers, now widely available online, supplement records and family stories with color and detail. Newspapers helped me identify the meaning behind a Valentine I found featuring my grandparents’ pictures. An article about my maternal grandparent’s engagement party noted that the found item was a party favor.

In 1922, my grandmother’s sister died in a car accident. As a child in the library basement, I discovered stories about Great Aunt Mae’s sudden death. The old-fashioned, over-the-top descriptive writing noted that the yellow roadster turned “turtle” into a ditch. But I forgot about this story until fifty years later, when I uncovered more newspaper stories, including a front-page piece with a large, dramatic headline from the Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette. The level of detail in the articles about this accident was overwhelming. My grandmother was just fourteen when her sister was killed. I can now more fully appreciate the trauma she and her parents must have suffered at this horrendous loss of a young, lovely schoolteacher.

Philip Graham, the late publisher of the Washington Post said, “Journalism is the first draft of history.” Without historical newspapers, I could not have completed my family projects. Details from multiple newspapers gave me the threads to weave disparate stories into my factual narrative.

Network with like-minded researchers

Historical newspapers are abundant (see below). In order to identify and access them, consult with librarians, genealogists, and like-minded friends who may know of resources you don’t. They may also belong to proprietary sites and can search for you. For example, a friend knew I had difficulty connecting the dots on an ancestor. Why did Reuben Long leave Dayton, Ohio, an established community for uninhabited Northeastern Indiana in the 1830s? My friend found an 1836 real estate ad in a Dayton newspaper using the location and date I suggested.

FARM FOR SALE—The subscribers will offer for sale on the premises, on Saturday, the 18th, at 10 a.m., a farm on which Reuben Long now resides, containing 80 acres six miles west of Dayton on Eaton Road. About one-half is improved. There is a dwelling house on the farm and a well of good water. Also—an apple orchard through which the National Road will undoubtedly pass—terms made known at the time of sale.

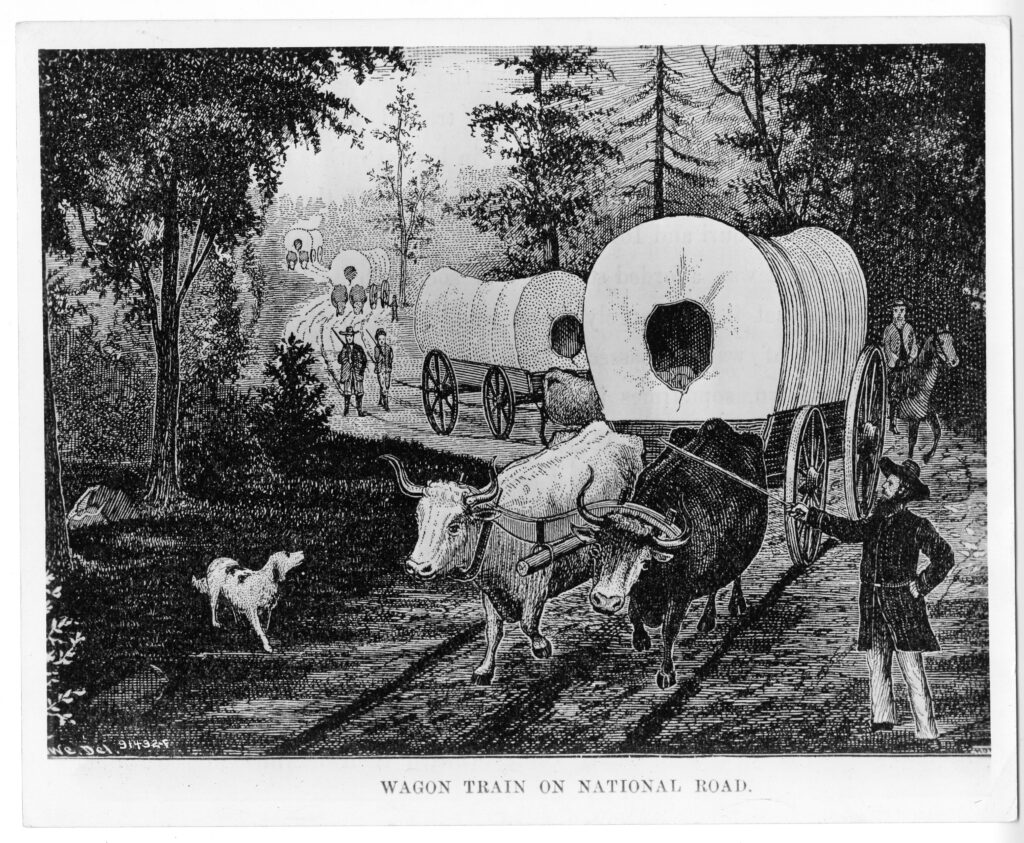

What I didn’t know, and was crucial for my book’s narrative arc, is why Reuben left Ohio. The new National Road would cut through his apple orchard, which could be financially detrimental. The National Road was the new nation’s first sizeable federal highway project, and it ran from Cumberland, Maryland to Vandalia, Illinois. I learned that the price of land in Indiana was half the price of land near Dayton. Thanks to a tiny 1836 classified in The Democratic Herald, I learned that Reuben sold his land and left for northeastern Indiana.

Indexes are your best friend.

Only some newspapers are indexed or even digitized. Some are available via microfilm and others via intact print copies at libraries and historical societies. When lucky enough to find an index, squeeze it for everything you can get by changing the way you search. I wanted to learn about my third great grandfather Jonas Baker. While his name was included in documents my grandmother shared, I never once heard her mention him. I looked in old newspapers for the answers to my questions: Did he have siblings? Was he a successful farmer? What happened to his children? Was he religious or civic-minded? How did he die?

I soon discovered why my grandmother never mentioned her great-grandfather’s name, though he passed 18 years before her birth. Details quickly spilled from the pages. Baker’s life was nuanced. He struggled with alcohol use disorder and shot himself in front of his family. An Indianapolis newspaper printed a blurb about his death in an afternoon edition later that same day, complete with macabre details.

There was more to his tragic life and death, of course. His obituary revealed important dates, names, and other nuances of his life. Jonas walked barefoot—his pockets full of gold coins—to Indiana from Ohio in the 1830s, where he bought 320 acres of land. Based on a grandson’s written account via a national genealogy site, I learned that he exhibited unusual behavior, like burying a cow, which had been struck by lightning, with the family Bible. However, he also demonstrated care for the community, taking baskets of food to needy neighbors.

Go beyond your hometown.

While I have fond memories of reading newspapers on microfilm reels in my hometown, unfortunately, I now live three hundred miles away. With the librarians’ help, I obtained obituaries, as well as information about weddings and school activities. I also searched for other local newspapers available digitally. Surprisingly, I found multiple articles about my ancestors and their community in newspapers. Sometimes I found news items that were relevant on a larger scale. For example, an 1862 article in The Indiana Herald discussed the Union’s big push for volunteers on the Western Front. My great-great-great-uncle Lewis Long volunteered at that time and died of dysentery after participating in the Battle of Vicksburg. His early death changed the trajectory of farm ownership.[i]

Could you check the small columns?

In 1971, my first job was at my hometown’s weekly newspaper, the South Whitley Tribune, the same paper I had read in the library basement. Besides learning to count em and en spaces for ads and running the string machine to bundle the papers, I gathered information from local villages for news columns.

These long-running columns noted anything you could imagine, from wedding showers to hospital admissions and discharges (long before HIPPA). And most small newspapers printed a version of these columns: Mr. Carl Enz, Tunker [my maternal grandfather], was admitted to Fort Wayne’s Lutheran Hospital on Tuesday for gall bladder surgery. I knew from my late mother that she, age ten, was admitted to the same hospital the next day and shared a room with her father. I have a picture of them in their side-by-side hospital beds. Now I knew the exact date.

Some newspapers featured columns called “Fifty Years Ago” and “Twenty-Five Years Ago.” If there is an index of the document you are searching, these columns are easily found. These articles—and I read dozens—often provided context for a particular date and time. One “Fifty Years Ago” column solved a family mystery. My grandmother had given me a picture of my great-grandfather Washington Long and his son standing beside a giant saguaro cactus. On the back of the photo, in my late mother’s handwriting, was the word “Tampa.” Great-Grandpa Long also went to Tampa every winter during the 1920s. I lived in Tampa during my husband’s graduate school years and didn’t remember seeing one saguaro cactus. This picture vexed me for many years until I found a tiny note in one of these columns, from November 1918, in a 1968 “Fifty Years Ago” column, reporting that Washington Long and his son Calvin had taken the train to Tempe, Arizona, where Calvin visited a tuberculosis sanitarium. Bingo! Tempe, not Tampa.

Although I used many sources in researching my articles and books, old newspapers elicited the most intriguing information, beyond what my grandmother had already discovered. Bringing the naïve reader into writing a family story, a magazine piece, or a novel means making it accessible. Readers must experience the lives of the people in their stories. Historical newspapers are a fantastic resource to find details to bring your narrative to life. What a gift for researchers to see, hear, smell, touch, and taste the world as those did in another time.

Where to find newspapers:

All Digitized Newspapers « Chronicling America « Library of Congress (loc.gov)

Don’t forget your county historical society and Indiana State Library. Indiana has two excellent genealogical libraries of national renown, the Fort Wayne-Allen County Public Library and the Willard Library in Evansville.

[i] Reuben’s son Washington Long, my great-great-grandfather, was given the farm from his remaining siblings in 1873. In his will, he divided his acreage between his children Anna and Calvin. Anna Long Hoard was the mother of my grandmother, LeNore Hoard Enz who gave it in life estate to my mother.