From June 12-14, scholars from all corners of the globe—including Cape Town, New Delhi, Toronto, Berlin, Peru, and Amsterdam—convened at San Francisco State University. Among them were Indianapolis historians Sam Opsahl (he/him), Jordan Ryan (they/them), and myself (she/her). The reason for this meeting of the minds?: the second ever Queer History Conference (QHC). Amidst the surreal beauty of the campus, lined by Muir Woods’s iconic redwood trees, we discussed universal research questions, learned about novel methodologies, and shared valuable resources. Considering how new the field of queer history is, I would be remiss not to discuss the insights gleaned at the QHC, many of which could be applied to various historical projects.

QHC attendees were a uniquely welcoming and curious bunch, although we were slightly intimidated by the number of people who decided to forgo compelling sessions like “Queering Women, Sex, and Youth in Colonial Settings” and “Legal Consciousness in Mid-Twentieth Century Queer and Trans History” in order to attend our panel. However, we felt immediately at ease presenting about those living on the margins of Indianapolis’s queer community, especially because our moderator Dr. Eric Gonzaba gave credence to Kurt Vonnegut’s observation that “wherever you go there is always a Hoosier doing something important there.”* Now an Assistant Professor of American Studies at California State University-Fullerton, Dr. Gonzaba grew up in rural southern Indiana and earned his BA from Indiana University. In his introduction, Dr. Gonzaba aptly noted that Indiana’s place in American queer history has been cemented both by the groundbreaking work of the Kinsey Institute and the controversial passage of the 2015 Religious Freedom Restoration Act.

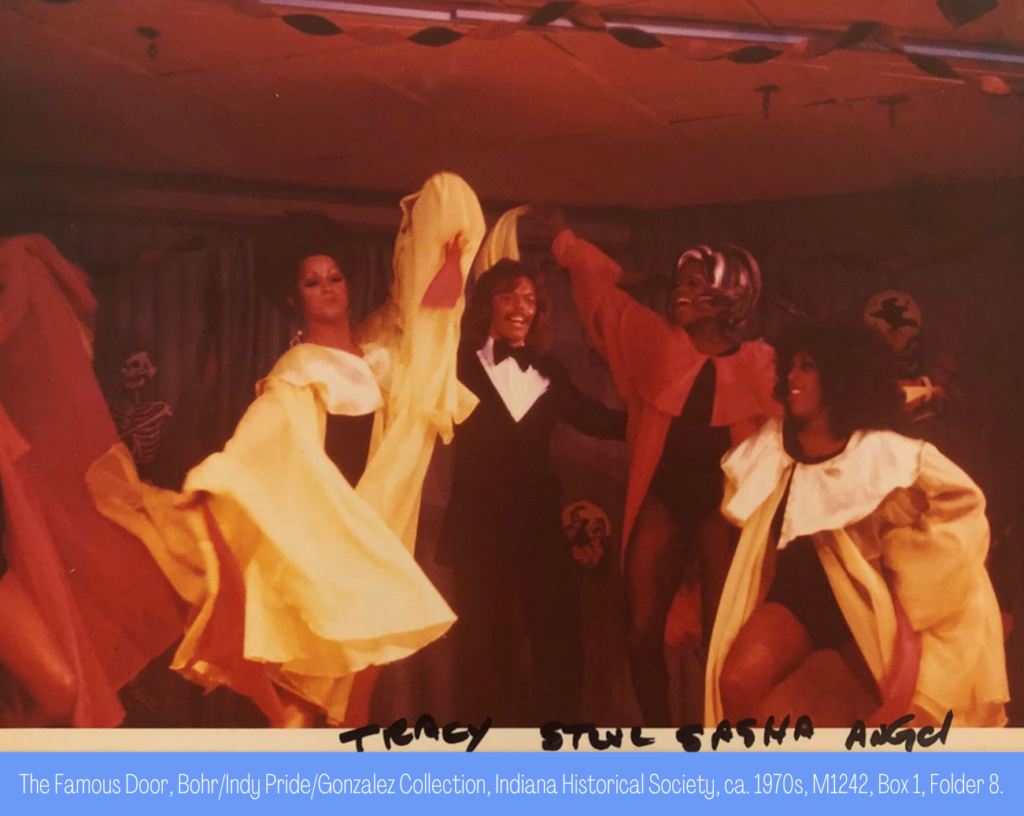

Jordan Ryan, architectural historian, activist-scholar, and founder of The History Concierge, kicked off our session. Ryan adapted their presentation from their paper, co-authored with Dr. Paul Mullins for the Journal for the Anthropology of North America, entitled “Imagining Musical Place: Race, Heritage, and African American Musical Landscapes.” Ryan focused on the erasure of Black cultural sites along Indiana Avenue, including venues like the Pink Poodle (later the Famous Door) and Log Cabin, which hosted popular drag shows in the first half of the 20th century. Ryan noted that although female impersonators were popular in vaudeville revues, “moral ideologues sometimes resisted openly queer drag performances.” This was reflected in one Indianapolis Recorder editorial about a show at the Paradise that attracted an audience of 2,000. The opiner wrote that “‘fairy’ (fag) (pansy) public stage show and dance . . . was a disgrace to this community.” Ryan concluded that:

Like much of the complex expressive culture that flourished on Indiana Avenue, female impersonators have not found a place in the public memory that has been crafted by ideologues whose representations of jazz have revolved around a very narrow dimension of the Indiana Avenue musical experience.

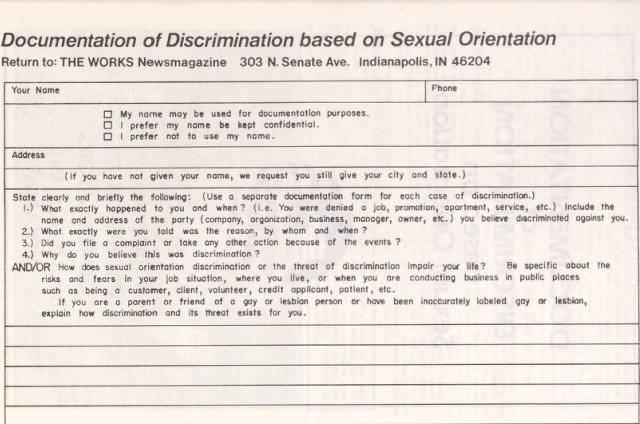

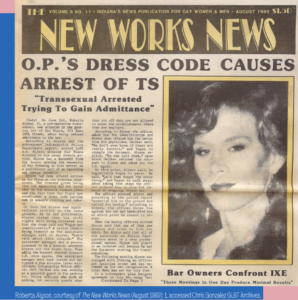

Following Ryan’s analysis of the built environment and public memory, I presented my work about the exclusion of gender non-conforming individuals at Indianapolis gay bars and the queer community’s effort to grapple with this discrimination. (A draft of my paper can be read here). On separate occasions in 1989, Our Place refused to serve patrons Kerry Gean and Roberta Alyson, resulting in public humiliation and, in Alyson’s case, arrest. Bar employees refused service on the grounds that Gean and Alyson—members of the Indiana Crossdresser Society (IXE)—did not meet dress code and their identification did not match their female-presenting appearance. Our Place was by no means the only Indianapolis gay bar to implement these policies and soon the pages of gay newsletter The Works teemed with editorials about the conflict. The majority of them condemned this discrimination, likening it to the prohibition of Black individuals at Riverside Park, while some agreed that such policies were necessary to preserve the bars’ masculine atmosphere.

Perhaps ironically, it was Indianapolis police officer and community liaison Shirley Purvitis who facilitated a meeting to try to resolve issues between “certain segments of the gay community.” Bar owners, IXE members, IPD vice officers, and members of the Indiana Civil Liberties Union and Justice, Inc. shared their experiences and discussed excise law. Although contentious, such meetings, coverage in The Works, and one-on-one meetings between IXE members and bar owners, led to the reversal of policies at many bars. The conflict illuminated the value of forums and facilitators and demonstrated how amplifying multiple perspectives resulted in greater inclusion.

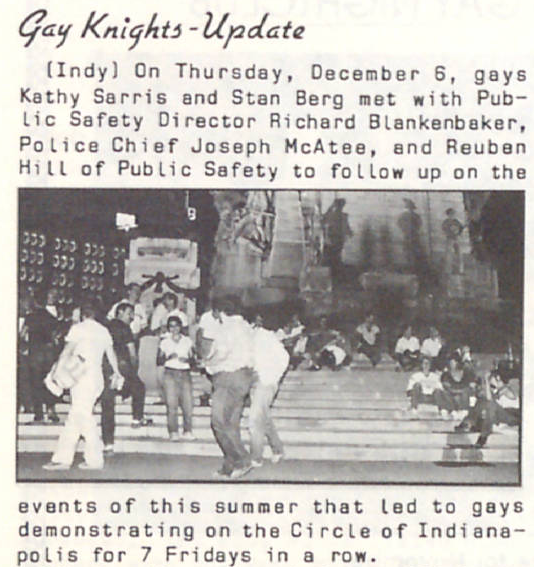

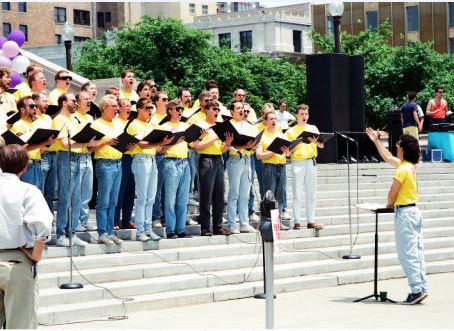

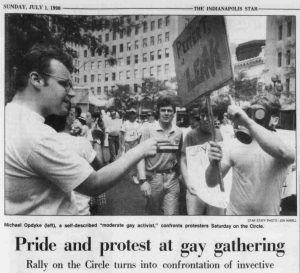

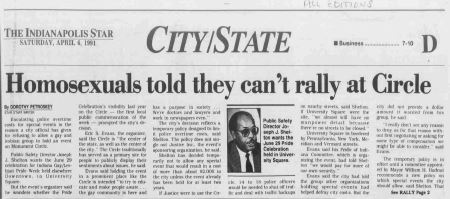

Sam Opsahl, program coordinator for Indiana Humanities, concluded our panel, presenting a paper adapted from his 2020 thesis, “Circle City Strife: Gay and Lesbian Activism during the Hudnut Era.” He highlighted the work of Justice, Inc. leader Kathy Sarris, noting that she “worked to insert the queer community’s narrative into public spaces by celebrating the gay and lesbian minority in public.” Opsahl positioned Sarris at the center of the local rights movement, ensuring that she will not be forgotten, unlike many lesbian activists whose work has been overshadowed by that of white, male leaders belonging to the middle class.

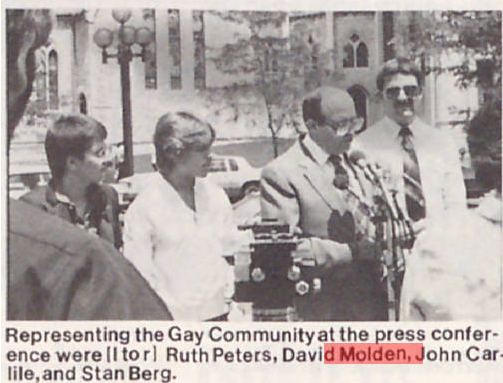

In 1983, through the Indianapolis Gay/Lesbian Coalition (IGLC), Berg and Sarris secured a meeting with Mayor William Hudnut, where they presented a list of seven recommendations. This marked the first time an Indianapolis mayor met with gay individuals to discuss issues facing the greater community. While the closed door meeting did not produce the results they hoped for, Berg and Sarris left feeling that “at least a dialogue had been initiated that they would continue to pursue should Hudnut be re-elected.” Opsahl contended that:

Mayor Hudnut, Berg, and Sarris contested the space on Monument Circle via protests and community celebrations, which rendered Indianapolis’ queer community impossible to ignore. Hudnut’s visions of an entrepreneurial city were endangered by the public debacles on Monument Circle, police discrimination, and the HIV crisis. Activists established their own dreams for citywide recognition that conflicted with Hudnut’s.

In listening to my colleagues’ presentations, fielding thoughtful audience questions, and receiving feedback from Dr. Gonzaba, I gained insight about Indianapolis’s queer past in real-time. It occurred to me that each of the individuals we studied had had to navigate the internalization of white, cisgender, heteronormative ideals by the LGBTQ community. We were left to ponder questions, like “What makes Indianapolis’s community unique?” and “How do we best document and memorialize queer history in a conservative region, in which anonymity provides safety?” The examination of intersectionality, as it relates to queer history, is relatively new and we hope our panel contributed to this field of study.

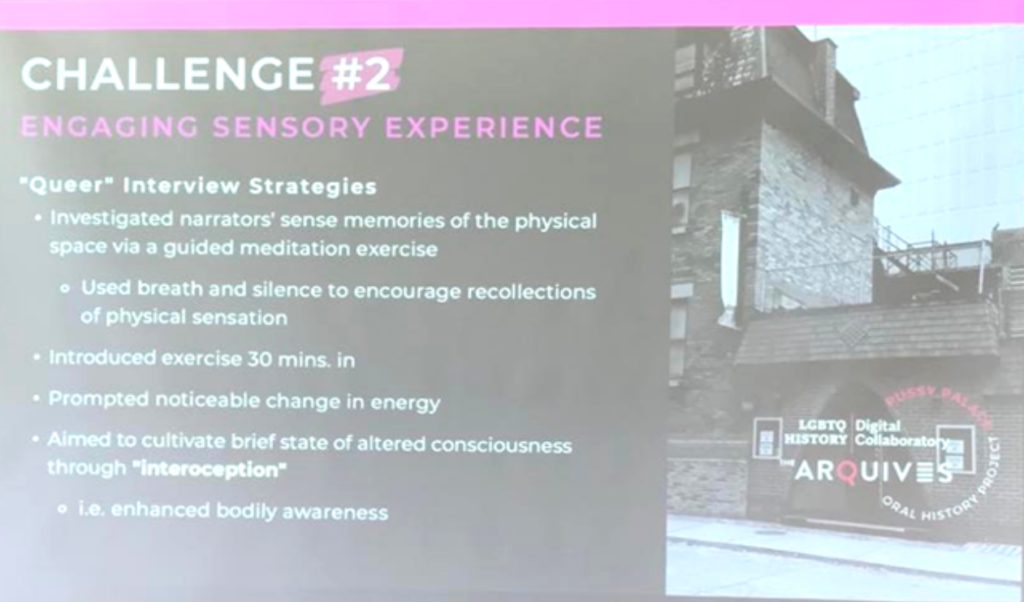

With our session mercifully scheduled for the first day, I was anxious to learn about others’ research findings and methodologies for the duration of the conference. I found the “Strategies for Documenting and Memorializing Queer History” panel to be particularly enlightening, as University of Toronto Professor Elspeth Brown’s presentation made me rethink how we conduct and use oral history interviews. Dr. Brown spoke about implementing novel interview strategies, such as utilizing guided meditation in order to engage interviewee’s senses. She found that this practice allowed subjects to both reinhabit and meaningfully relay the past.

Dr. Brown and her team have also given much thought to the question of utility, asking themselves: “Is the main purpose of conducting interviews to create a primary source for future historians to draw upon? Or is their value entrenched in telling relevant stories to modern audiences?” Regarding the latter, Dr. Brown is mindful of a study that found people listen to only half of an oral history interview, regardless of whether it is one minute or three hours long. Therefore, her team tried to think creatively about how to capture listeners’ attention. They hired an illustrator and sound engineer to recreate settings described by interview subjects. Pairing the animated sequences with two minute interview segments provided a multisensory experience. Dr. Brown played one such clip for the audience and I think we were all stunned by how immersed we were in the story.

Slide from Professor Elspeth Brown’s presentation about novel oral history interviewing techniques.

While attention has certainly been paid to illuminating history through social media, San Francisco State University Master’s student Jesse Ataide’s presentation “Imagining the Queer Past on Instagram” probed issues unique to queer history. Ataide initially created his account @queer_modernisms to share interesting images he came across in his research, which focused on the period between 1890 and 1969. However, when the account rapidly grew in followers (it is now up to 26,000), he realized he needed to be more intentional about how he curated content. He became ever-mindful of the question “who and what is queer?,” noting that many images circulated online appear queer to the “contemporary eye,” but can easily be misinterpreted. These include fascist/Nazi images that glorify the male body and “same sex intimacy across different eras and cultures.” Ataide noted that the subjects of such images may have actively resisted the “queer” designation and that “unambiguous self-identification” is certainly the exception, not the norm. So, in order to avoid outing or misinterpreting someone’s sexual identity, he tries to “find mention or evidence of queerness in academic, published, or other authoritative sources before posting.”

He also discussed the importance of representation. Images of white, masculine, middleclass male subjects garner the highest rates of engagement, so he is currently strategizing how to amplify diverse content without losing his platform. Ataide left us with many insightful questions to ponder, especially about how best to create a “useable past.”

My time at SFSU concluded with a roundtable comprised of both academic press editors and scholars whose work has been published by such presses. Larin McLaughlin, Editor in Chief at the University of Washington Press, emphasized the importance of vision when crafting and pitching a book idea. It is not enough that your topic has never been written about before, but you should able to articulate to a publisher how your work moves the field forward. Finding an editor that shares your set of goals is also crucial in executing your vision. McLaughlin encouraged writers to focus on interdisciplinary topics, as they appeal to audiences outside of history. Dominique J. Moore, Acquisitions Editor for the University of Illinois Press, noted that a well-executed introduction chapter goes a long way in convincing an editor to publish your work. She also advised crafting a table of contents that contains a summary of each chapter’s arguments and sources, as well as how the chapters relate to one another. When considering your audience, ask yourself, “What conference do I want to see my book at?” Write for those attendees.

Panelists also articulated the differences between trade and university presses. They noted that whereas trade presses typically have much bigger marketing budgets that can be used to quickly advertise your book to a broad network, academic presses provide longevity, as they continue to publish books long after the first printing. Similarly, trade presses sometimes present more obstacles to publication, as aspiring authors have to convince an agent who then needs to convince an editor about your work. For the self-doubting historian, their reassurance about the peer review process was liberating: ultimately, you can and should push back against critiques that you vehemently disagree with. You are the expert, after all.

In a field dominated by stories of stigma, violence, and oppression, the 2022 QHC provided a much needed opportunity to learn about LGBTQ individuals who thrived, helped build community, and furthered human rights. It was invigorating to be around scholars equally humbled and excited to be part of this nascent field. The conference also provided reassurance that I am on the right track in terms of respectfully telling balanced, accurate histories about LGBTQ Hoosiers. Likewise, it revealed to me that people genuinely are curious about queer life in the Midwest. But before delving back into the pages of The Works, this midwestern historian is closing her eyes and revisiting San Francisco’s winding roads, dotted with colorful condominiums and flanked by glimmering beaches.

* IUPUI anthropology professor Paul Mullins was originally slated to moderate our session. Although Dr. Mullins was unable to make it, he was with us in spirit and scholarship.