[This post is adapted from a footnoted research paper created to support the text of the Edwin Way Teale state historical marker.]

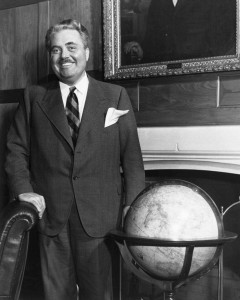

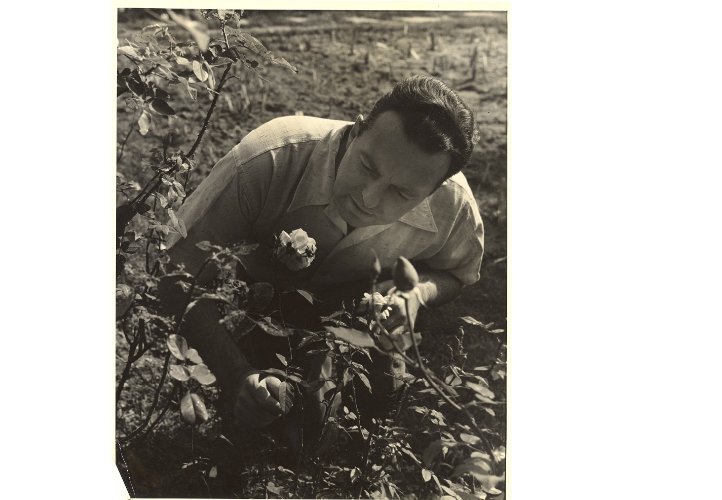

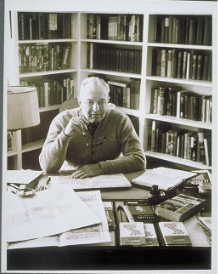

American naturalists have been cited for combining philosophy and writing in ways that affect how concerned citizens value and care for their environment. Edwin Way Teale is considered one of the twentieth century’s most influential naturalists, stemming from his ability to combine the artistic, philosophical, and scientific in his writing. According to the extensive Biographical Dictionary of American and Canadian Naturalists and Environmentalists, “Through his popular books [Teale] convinced Americans they had a personal stake in the preservation of ecological zones [and] convinced them to support national parks and conservation movements.” Teale credited his renowned career to his rich childhood spent in the Indiana Dunes, where he developed a love for nature, an eye for photography, and an accessible writing style.

He immortalized his boyhood adventures in Dune Boy and later works, including Wandering through Winter, for which he became the first naturalist to win a Pulitzer Prize. Teale is included in the “heyday of dunes art and literature begun and perpetuated” by a group of artists of the “Chicago Renaissance” movement, according to J. Ronald Engel’s Sacred Sands: The Struggle for Community in the Indiana Dunes. Naturalists, conservationists, writers, and critics have ranked Teale among the renowned American naturalists, including John Muir, John Burroughs, and Henry David Thoreau.

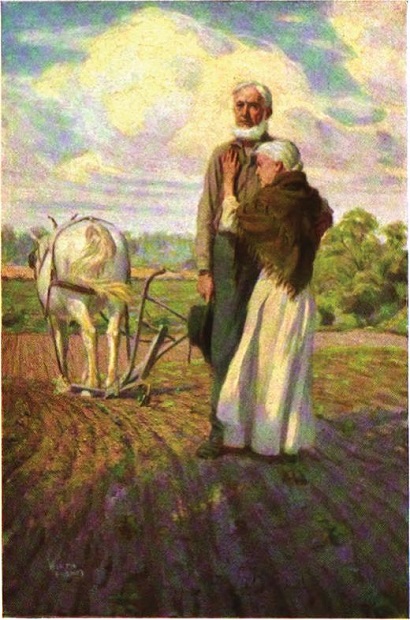

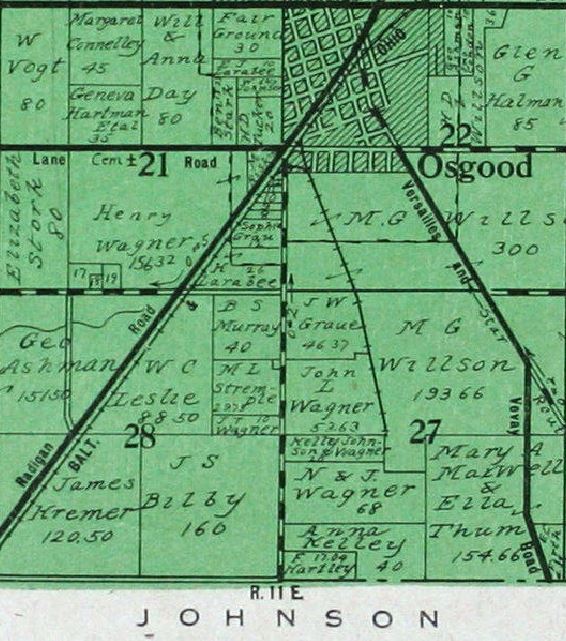

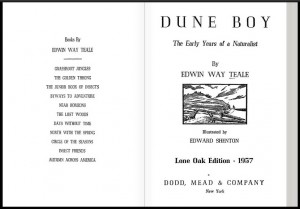

Born Edwin AlfredTeale on June 2, 1899 in Joliet, Illinois. He later wrote of his disdain for the dismal industrial landscape of his parents’ home. Instead, Teale favored the holidays and summers he spent with “Gram and Gramp” exploring their Lone Oak farm in the Indiana Dunes. In Dune Boy (1943), Teale wrote that “to a boy alive to the natural harvest of birds and animals and insects, [Lone Oak] offered boundless returns.”

As he grew up, Teale’s interest in nature grew as well. At the age of seven or eight Teale looked through his first microscope, and at nine he declared himself a naturalist. By the age of ten he finished his twenty-five chapter “Tails [sic] of Lone Oak,” and at twelve he changed his name to “the more distinguished” Edwin Way Teale.

In 1918, Teale enrolled at Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana; he graduated with a bachelor’s degree in English literature in 1922. On August 1, 1923, Teale married his college sweetheart Nellie Imogene Donovan, who would become his “partner naturalist.”

The Teales moved to New York City in 1924, where Edwin attended Columbia University, and continued writing. After a period of rejection, he obtained regular work assisting Frank Crane, a popular religious writer, with his daily editorial column. The Teales’ only child, David, was born in 1925. In 1926, Teale received his M.A. from Columbia in English literature. In July of that year, he also took possession of his grandparents’ property in the Indiana Dunes, where he and his family built a brick cottage. They maintained the property until selling it in 1937.

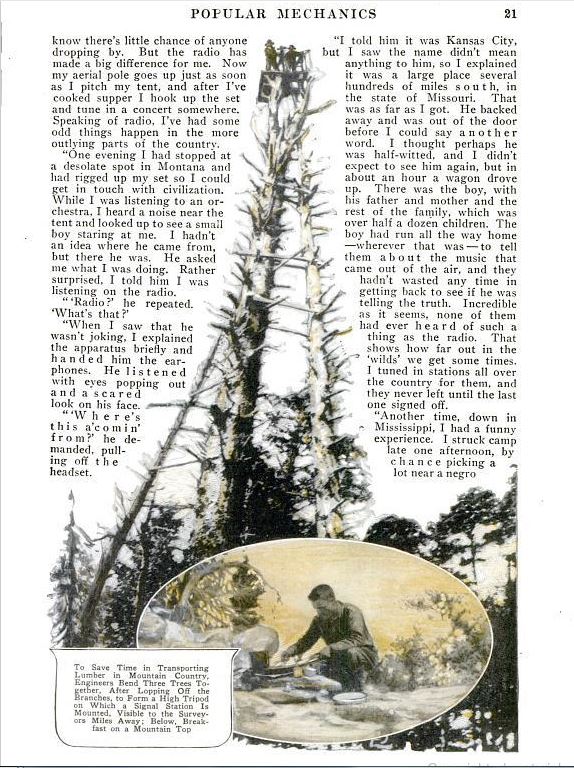

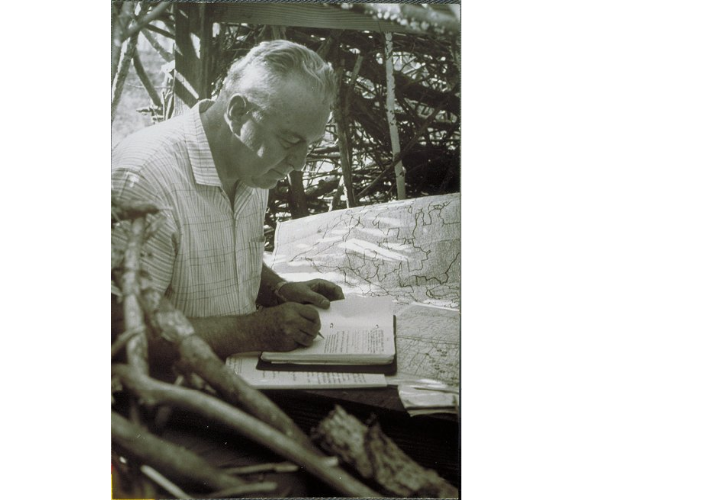

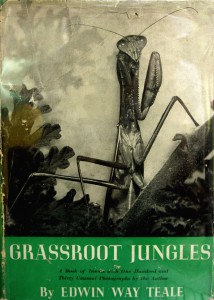

In 1928, Popular Science hired Teale as a staff writer. Over the next thirteen years, he perfected his photography skills at the magazine, which led his pioneering technique for photographing insects and launched his career. Teale used an icebox to immobilize his insect subjects, placed them in a natural surrounding, set up a camera with magnifying lens, and waited for the subject to reanimate. Using this technique, he represented insects in a novel way – up close and larger than life. After successfully exhibiting his photos around New York City, they were published in nature magazines. His first critically acclaimed book, Grassroot Jungles, displayed a collection of over one hundred of these photos.

In January 1941, Teale’s The Golden Throng was published, receiving praise for the photographs of bees. On October 15 of that year, Teale left his job at Popular Science to become a freelance writer and photographer. He called that day his “own personal Independence Day.”

Teale’s decision to undertake freelance writing and photography also gave him time to work in his insect garden. For several years, Teale paid ten dollars a year for “insect rights” for a plot of land near his Long Island home. He planted “sunflowers, hollyhocks, spice bush and milkweed,” as well as “troughs offering honey and syrup to bees and butterflies (and) hidden pie pans with putrid meat to attract carrion beetles” to his garden. Teale’s biographer and publisher, Edward H. Dodd, wrote that “this small plot of land, undesirable for real-estate purposes, even in Long Island became his outdoor laboratory, his photography studio, his wilderness to explore.”

In October 1942, Dodd, Mead & Company published the result of these photography experiments, Near Horizons: The Story of an Insect Garden. Prominent publications praised the book, including the New York Times, Scientific Monthly, and The Scientific American, which proclaimed Teale one of few scientists “heavily gifted with literary charm.” In this latest book, Teale described himself as “an explorer who stayed at home, a traveler in little realms, a voyager within the near horizons of a hillside.”

In October 1943, Teale published Dune Boy: The Early Years of a Naturalist. In this work, Teale recollected the years he spent among the natural wonders of the Indiana Dunes, surveying his surroundings from the roof of the farm house, the shores of Lake Michigan, and the floor of the surrounding woods. In the book, he credits his grandparents for giving him freedom to develop his interest in nature. “At Lone Oak there was room to explore and time for adventure. A new world opened up around me. During my formative years, from earliest childhood to the age of fifteen, I spent my most memorable months here, on the borderland of the dunes.”

Dune Boy received a long and glowing review in the New York Times. The reviewer alluded to the book and Teale’s childhood, as representative of something inherently American. The reviewer stated that “Dune Boy is not only the record of a naturalist’s beginnings but one of our many-sided American way of life.”

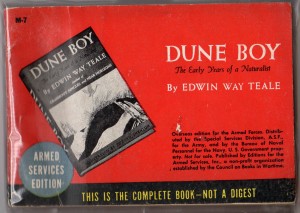

Indicative of the book’s popularity, the army distributed more than 100,000 copies of Dune Boy during World War II. These “armed service editions” were printed by the Council on Books in Wartime.” Their slogan was “books are weapons in the war on ideas.”Teale commented that “he heard from many who had read it while engaged in battle for freedom in all parts of the world” and some scholars have suggested that the book presents “a timeless model of the democratic common life, for many . . . an image of their real American homeland.” The Teales’ son, David, served as part of an assault team under General George Patton during the war. After a period of considering him missing in action, in March 1945 the Teales’ received word that their nineteen-year-old son had been killed. The Teales claimed that only their love of nature got them through this difficult time.

Despite the personal tragedy, Teale’s career flourished. On November 19, 1945, The Lost Woods: Adventures of a Naturalist was published with critical acclaim and, beginning in January 1946, newspapers across the country began running Teale’s Nature in Action column. That November, Dodd, Mead & Company released a version of Henry David Thoreau’s Walden, “lovingly prepared” by Teale, who wrote an introduction and provided 142 of his own photographs.

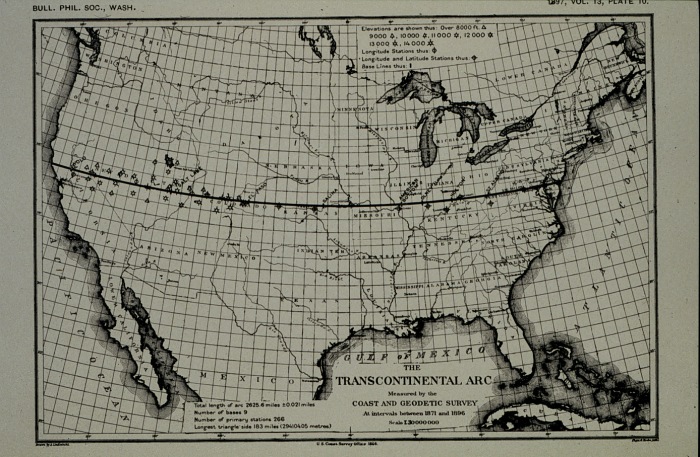

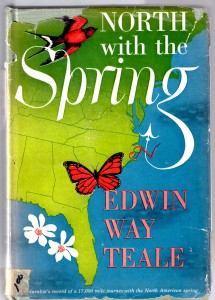

In November 1951, Dodd, Mead & Company released North with the Spring, the account of the Teales’ 17,000-mile, four month long pursuit of spring across America. According to one New York Times reviewer, the book was “packed with solid learning” about the plants, animals, and weather they encountered, but it was also a “warm and moving” story of husband and wife naturalists. Contemporary environmentalists, such as Rachel Carson, embraced North with the Spring‘s environmentally conscious message.

On December 16, 1951, Teale began writing for the New York Times, producing the first of many nature articles and book reviews. In his first article, Teale wrote of the efforts to protect the wildlife areas and lamented the increasing urbanization and encroaching suburbs. Teale also wrote about the importance of contact with nature “to restore mental tone and health,” a common concern among conservationists during this time period.

Over the next few years, Teale produced compilations of selected nature writing, including Green Treasury: A Journey through the World’s Great Nature Writing (1952) and The Wilderness World of John Muir (1954), which made the New York Times “outstanding books of the year” list. [Buy it at the IHB Book Shop.] Reviewers called Teale “one of our most sensitive and observant naturalists” and among the “best of Americans writing about nature,” comparing him to Thoreau and Burroughs. Teale attended conservation fundraisers and entomological meetings. As his popularity grew, his earlier books were reprinted and adapted into children’s versions.

In August 1956, Teale published Autumn Across America, the second book in the American Seasons series. This time, the Teales followed fall through twenty-six states from Cape Cod to California over three months. Autumn Across America received even greater acclaim than North with the Spring. It was presented to the White House Library and described as a “revelation of the seasonal wonders that lie around us and the reflections they caused in the searching mind and genial soul of the author.”

In 1959, the Teales left their Long Island home, due to increased population and suburbanization, and moved to a 130-acre estate in Hampton, Connecticut, which they named Trail Wood.

In fall 1965, Teale published Wandering through Winter, the most celebrated of all his works. Teale covered a wide range of topics from beetles to whales to sunsets. The New York Times ran a laudatory review of Wandering through Winter, praising Teale’s work as without fault and his writing as combining the best of Thoreau, Hudson, and Muir. In May 1966, Teale became the first naturalist to win a Pulitzer Prize (for general nonfiction) for Wandering through Winter.

Although he continued to contribute introductions and chapters to colleagues’ books, and have his own books reprinted and adapted as children’s stories, his publishing slowed somewhat over the next decade. On October 10, 1970, Indiana University presented Teale with an honorary degree. In 1978, Teale produced his last work, A Walk through the Year. The book summarized a year with his wife Nellie at Trail Wood, highlighting the memorable experiences they shared.

On October 18, 1980, Teale died at the age of 81. On May 17, 1981, the Connecticut Audubon Society dedicated Trail Wood as the Edwin Way Teale Memorial Sanctuary, and it became steward of the property. Nellie remained at the farm until her death in 1993. In 1998, the University of Connecticut initiated the Edwin Way Teale Lecture Series. Visitors come to hike the grounds to see Teale’s landscape of “woods, open fields, swamps, two good-sized brooks and a waterfall.” Teale’s works continue to be reprinted, including a reissue of Dune Boy in 2002.

In 2009, the Indiana Historical Bureau, with the support of the Musette Lewry Trust, installed a state historical marker at the “Lone Oak” site where the brick cottage built by Teale still stands.