Last Sunday I went for a walk . . . I did not walk alone.

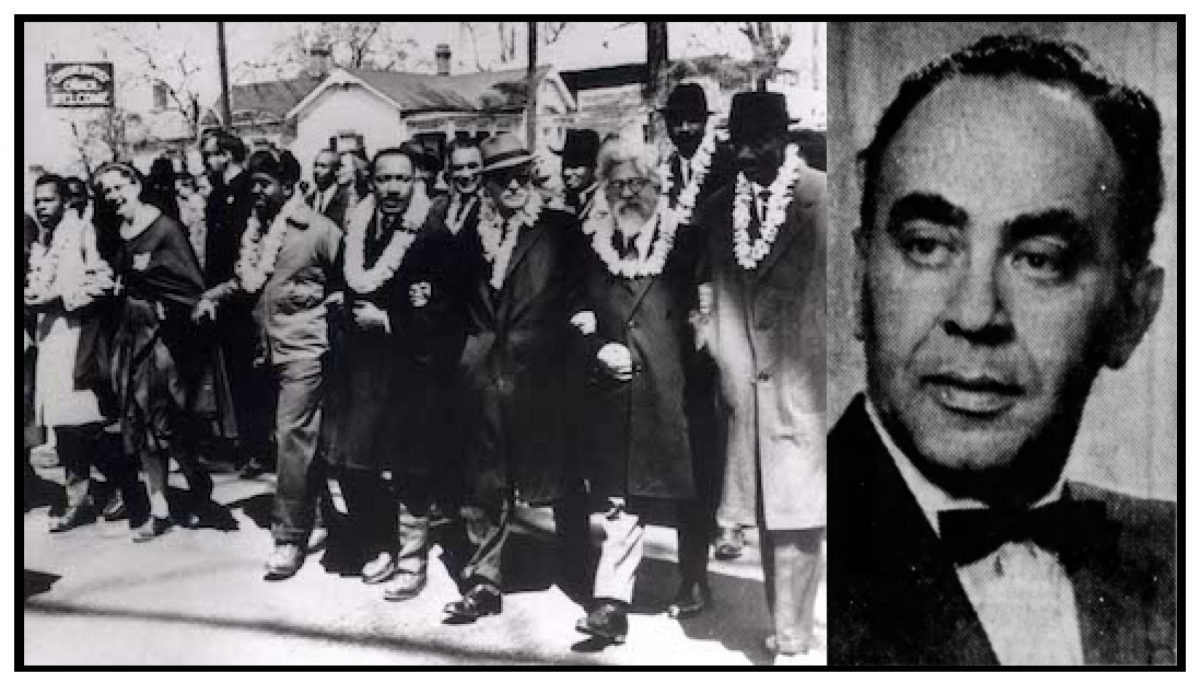

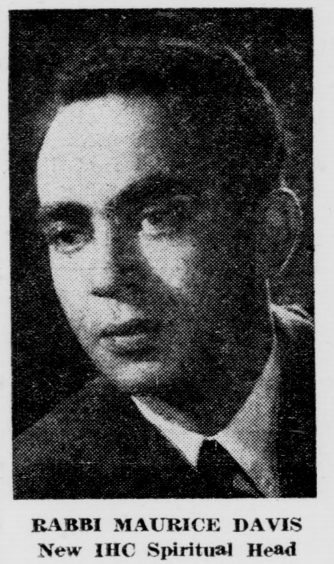

With these simple words Rabbi Maurice Davis described his 1965 trip to Selma to the readers of the (Indianapolis) Jewish Post. Rabbi Davis’s “walk” was a protest led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. against institutional racism, voter suppression, and violence against African Americans. When King asked civil rights leaders from around the country to join him in Alabama, Davis had no question that it was his duty to join the demonstration of solidarity. Davis had long worked for civil rights through both secular and faith-based channels. He advocated for community action in his sermons to the Indianapolis Hebrew Congregation. He led several civic action councils that combated segregation, racist policies, and poverty. And he extended his appeal for civil rights to the entire city through a regular newspaper column and a television show. Mostly, however, Rabbi Davis marched at Selma “because it was right.”

“You Were a Spark for Us”

Maurice Davis was born in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1921. Census records show that his Russian-born father Jacob managed a garage while his mother Sadie cared for five children. They did well for themselves and were able to send Maurice first to Brown University in 1939 and then to the University of Cincinnati where he received his B.A. in 1945. He then received his Master of Hebrew Letters from the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. After serving several different congregations as a student rabbi, he became rabbi of Adath Israel in Lexington, Kentucky in 1951. By this point he was already active in the local civil rights movement and joined the Kentucky Commission Against Segregation.

Maurice Davis was born in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1921. Census records show that his Russian-born father Jacob managed a garage while his mother Sadie cared for five children. They did well for themselves and were able to send Maurice first to Brown University in 1939 and then to the University of Cincinnati where he received his B.A. in 1945. He then received his Master of Hebrew Letters from the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. After serving several different congregations as a student rabbi, he became rabbi of Adath Israel in Lexington, Kentucky in 1951. By this point he was already active in the local civil rights movement and joined the Kentucky Commission Against Segregation.

Rabbi Maurice Davis became the spiritual leader of the Indianapolis Hebrew Congregation (IHC) in March 1956, in time to celebrate the centennial of its founding in 1856. Over 600 families made up the large congregation which was in the process of planning their new temple at 64th and Meridian, which still houses the IHC today (a move from their earlier location at the Market Street Temple.) As the ninth Rabbi serving the IHC, Davis continued to advance the forward-thinking Reform Judaism of his predecessors, according to the Jewish Post. In his first year, he attracted eighty new congregants, and temple brotherhood president Herman Logan wrote in the congregational bulletin:

Rabbi Maurice Davis became the spiritual leader of the Indianapolis Hebrew Congregation (IHC) in March 1956, in time to celebrate the centennial of its founding in 1856. Over 600 families made up the large congregation which was in the process of planning their new temple at 64th and Meridian, which still houses the IHC today (a move from their earlier location at the Market Street Temple.) As the ninth Rabbi serving the IHC, Davis continued to advance the forward-thinking Reform Judaism of his predecessors, according to the Jewish Post. In his first year, he attracted eighty new congregants, and temple brotherhood president Herman Logan wrote in the congregational bulletin:

You were a spark for us which turned into a flame when a new brotherhood was beginning.

It was an auspicious start for the young rabbi.

“Something Less Than Welcome”

While the IHC welcomed Rabbi Davis, his wife Marion, and their sons Jay and Michael, some other Hoosiers made the Davis family feel “something less than welcome.” In 1959, the Jewish Post reported that Rabbi Davis’s son Jay was denied entry to the Riviera Club‘s swimming pool at 5640 North Illinois Street. The Rabbi told his congregation that Jay unfortunately learned first about the club’s “wonderful slide” and then its anti-Semitic policies. Jay summarized the situation as only a child could, stating: “Gee whiz, dad, it isn’t fair.” The Rabbi then had to explain the difference between legal segregation and social segregation to his son. The rabbi told his congregation that while many people think segregation in the private sphere “has no meaning” and should be tolerated, it does have meaning to the people it affects. And in this case, the meaning was that a nine-year-old boy was made to feel inferior to his peers.

The Jewish Post pursued the story, reporting on a survey of five “exclusive” Indianapolis clubs. Each club, including the Riviera Club, claimed not to discriminate against Jews. Some of the club chairmen and presidents even claimed they had Jewish members. However, when the Jewish Post interviewed the club managers, they reported that they knew of no Jewish members. Others in the club leadership claimed no Jews had applied for membership or that they did not keep track of religious affiliation. From the perspective of the Post, none gave a straight answer.

Rabbi Davis did not only respond to discrimination when it was personal. He believed that it was his responsibility, and that of all religious leaders, to work for moral justice. Not all of his Jewish colleagues agreed. In response to a 1960 Indianapolis Times poll of religious leaders (reported by the Jewish Post), two of Indianapolis’s leading rabbis (Congregation B’nai Torah and Shara Tefila) reported that clergy should keep out of politics. Rabbi Davis, on the other hand, said it was the responsibility of the synagogue to help inform members on political issues, to encourage them to be active participants in government, and “to speak up whenever morality or ethics are involved in politics.”

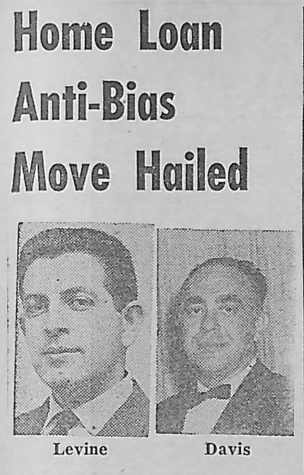

Rabbi Davis not only advocated for equality for Jews, but all people facing oppression. He encouraged Jews to look beyond their own community and work to end discrimination everywhere. He stated, “A decent and sensitive America is good for all Americans and we must help her be so” (more here). Indianapolis’s African American community took note. In 1960, the Indianapolis branch of the NAACP named Davis its “honorary chairman” and the Indianapolis Recorder reported regularly on his efforts to fight segregation and inequality. As president of the Indianapolis Human Relations Council, Davis worked to end racist mortgage and loan policies that denied fair housing to African Americans and created segregated neighborhoods (more here). He conducted personal investigations of restaurants and other establishments which had reputations for discriminating against African Americans and reported his findings in the Jewish Post (more here). By 1962, he had a regular column giving his views on issues of the day and often advocating for civil rights.

Rabbi Davis not only advocated for equality for Jews, but all people facing oppression. He encouraged Jews to look beyond their own community and work to end discrimination everywhere. He stated, “A decent and sensitive America is good for all Americans and we must help her be so” (more here). Indianapolis’s African American community took note. In 1960, the Indianapolis branch of the NAACP named Davis its “honorary chairman” and the Indianapolis Recorder reported regularly on his efforts to fight segregation and inequality. As president of the Indianapolis Human Relations Council, Davis worked to end racist mortgage and loan policies that denied fair housing to African Americans and created segregated neighborhoods (more here). He conducted personal investigations of restaurants and other establishments which had reputations for discriminating against African Americans and reported his findings in the Jewish Post (more here). By 1962, he had a regular column giving his views on issues of the day and often advocating for civil rights.

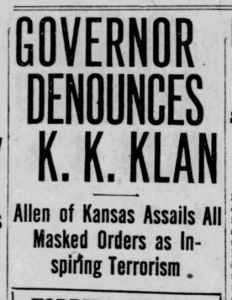

His columns were often fiery calls to action. For example, in September 1963, he responded to the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Alabama where four African American children were killed “while putting on their choir robes.” Rabbi Davis, however, blamed not just the bomber and not just the racism and negligence of the governor and police chief, but “every American citizen who participates in prejudice or fails to oppose it.” His powerful arguments against injustice were often shaped by the legacy of the holocaust. He continued:

His columns were often fiery calls to action. For example, in September 1963, he responded to the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Alabama where four African American children were killed “while putting on their choir robes.” Rabbi Davis, however, blamed not just the bomber and not just the racism and negligence of the governor and police chief, but “every American citizen who participates in prejudice or fails to oppose it.” His powerful arguments against injustice were often shaped by the legacy of the holocaust. He continued:

Segregation and discrimination, lead to bombing and lynching as surely as anti-Semitism leads to Auschwitz and Buchenwald. And any man who walks that path, has not the right to be amazed where it leads. We who know the end of the road, must say this openly, and believe this implicitly, and practice it publicly. And privately. And always.

Not long after his article on the bombing, Rabbi Maurice Davis received a bomb threat of his own.

“My Name Was One of Them”

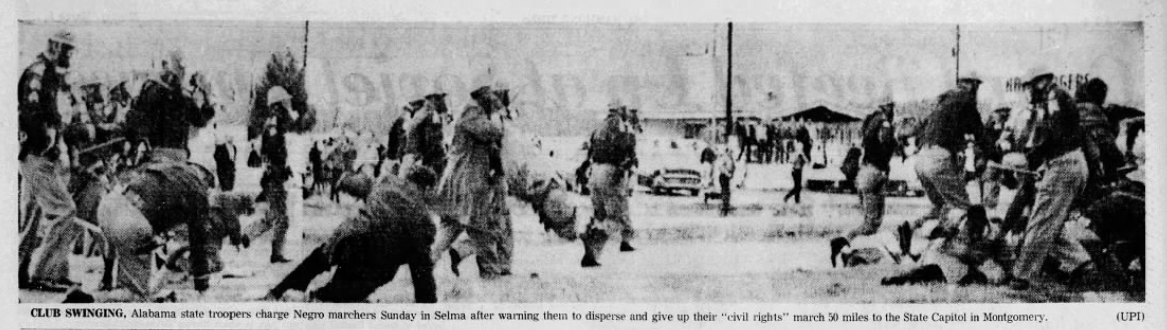

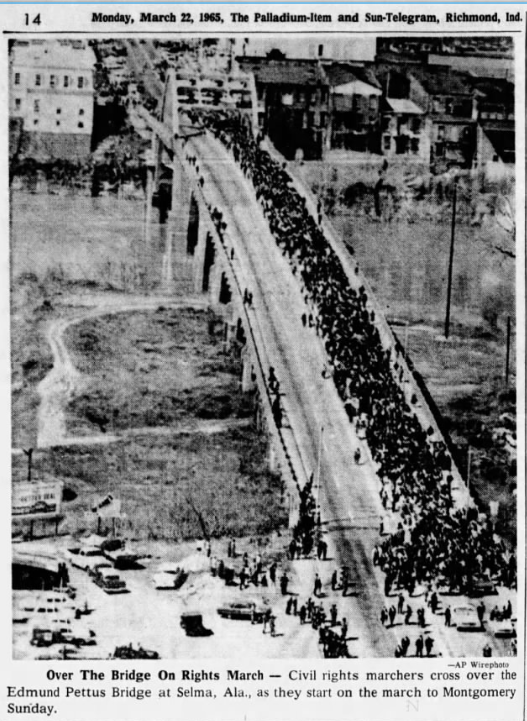

By 1965, the civil rights movement had reached its “political and emotional peak” with three marches from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, to protest the suppression of African American votes and the recent killing of activist Jimmie Lee Jackson (more here: International Civil Rights Center and Museum). On March 7, the protesters led by John Lewis began a peaceful march, but were soon stopped at the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma by state troopers and Dallas County police who were waiting for them. In an incident remembered as “Bloody Sunday,” police violently attacked the unarmed demonstrators with clubs and tear gas. Police beat Lewis unconscious. On March 9, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. flew to Selma and called for others to join him. That day, a larger group followed King back to the bridge to kneel in prayer, but dared go no further as a federal judge had issued a restraining order against the march. Many were disappointed that King did not attempt to march on toward Montgomery. Others, however, credit his concession with expediting the passage of the Voting Rights Act.*

The night of the second march to the bridge a group of white men killed Unitarian minister James Reeb who had traveled to Selma from Boston to join King. Related protests erupted across the country and King called for a third march. On Sunday, March 21, civil rights leaders and supporters from around the country arrived in Selma to march over the infamous bridge to Montgomery. Rabbi Maurice Davis would march in the front lines.

When the Indianapolis Star reported that Rabbi Davis and David H. Goldstein (of the Indianapolis Jewish Community Relations Council) had left for Selma, the newspaper estimated that these Hoosiers would join around 300 people. Instead, Davis reported that they joined thousands at Brown Chapel Methodist Church for a ceremony before the march. Davis described their arrival at the church:

As we approached Selma we saw the Army begin to position itself. Jeeps and trucks filled with soldiers, hospital units, and communications experts clustered along the way . . . The road leading to the church was lined with National Guardsmen, recently federalized.

While President Johnson ordered National Guard protection for the marchers to avoid a repeat of “Bloody Sunday” and its ensuing protests, the atmosphere was still tense. Davis and Goldstein met with some other rabbis after the service who had arrived before them. These rabbis told them that they were unable to buy a meal or place to stay, the reason being the Selma residents insisted on giving the activists whatever they needed.

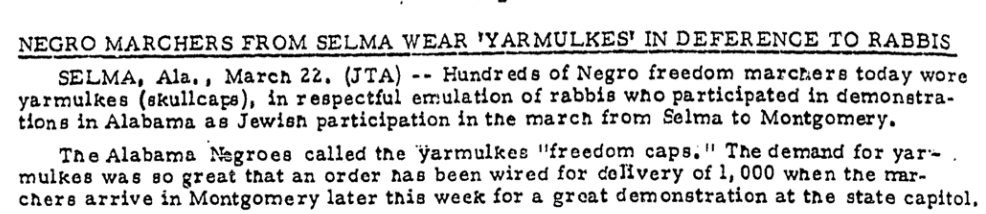

Davis and Goldstein also looked to find out from the other rabbis where they could get yarmulkes, as a shipment was supposed to have recently arrived. Organizers wanted Jewish demonstrators from all branches of the faith to be as clearly visible as those of other faiths to show their support and numbers. They told Davis, “It is our answer to the clerical collar.” However, Davis and Goldstein had trouble finding one. They soon learned why.

Two days earlier, five rabbis were jailed for taking part in demonstrations. After holding Sabbath behind bars Friday, they announced they would hold a service in front of the Brown Chapel after their release on Saturday. According to the Jewish Post, “Over 600 Negroes and whites, Jewish and non-Jews joined in the impromptu havdalah services for one of the most unique of its kind in history.” According to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, those in attendance, regardless of their faith, donned yarmulkes “in respectful emulation of rabbis who participated in demonstrations.” In Selma, they became known as “freedom caps.” Davis reported that “all the Civil Rights workers wanted to wear them . . . That is where all the yarmelkes went!”

Dr. King entered the chapel at 10:45 a.m. Sunday. Davis was asked if he would represent the Union of American Hebrew Congregations. When he agreed, he was pulled up onto the platform next to King during the latter’s “magic” sermon. Davis explained:

Nothing but the word “magic” can quite describe what it is he does to so many. When King speaks, you are not an audience. You are participants. And when he finished we were ready to march.

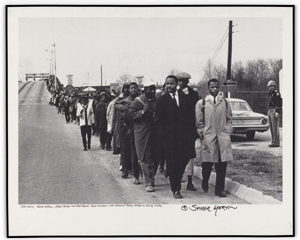

The thousands of demonstrators were organized into rows with the first three rows chosen by Dr. King. Davis stated:

Before the march began a list of 20 names were read to accompany Rev. King in the first three rows, and my name was one of them. I marched proudly at the front . . .

He continued:

On the street we formed three rows of 8, locked our arms together, and started to march. Behind us the thousands began to follow.

When they arrived at the infamous bridge they paused to remember those who came before them and were attacked. They continued onto the highway. The road was lined with armed National Guardsmen and five helicopters circled the group. State troopers were taking pictures of the marchers. Davis explained:

This is an Alabama form of intimidation. I kept remembering that these were the same state troopers who two weeks earlier had ridden mercilessly into a defenseless mass of people . . . We kept on marching.

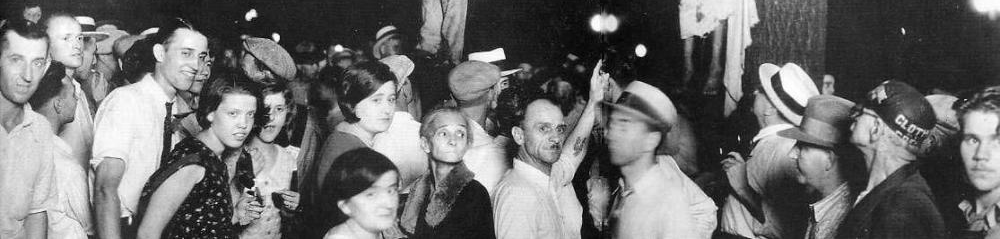

The marchers passed people who “waved, wept, prayed, and shouted out words of encouragement” and others, “whites who taunted, jeered, cursed” or “stood with stark amazement at this incredible sight.” At one point they passed a car painted with hateful signs “taunting even the death of Reverend Reed.” Other signs read “Dirty communist clergy go home” and “integrationist scum stay away.”

Rabbi Davis marched for twelve hours without sitting down or eating. Unfortunately, Davis did not get to finish the march. Instead, he was called to fly to Cincinnati that night to be with his father-in-law who had been admitted to the hospital with a serious illness. When Daivs finally returned to Indianapolis, he was welcomed with a threatening phone call.

“It’ll be too late when it goes off.”

When Rabbi Davis answered his phone Monday night at 11:00, an anonymous man asked if he was “the rabbi who went to Selma.” When Davis answered affirmatively, the voice continued: “Let me check this list again . . . You are No. 2 in Indianapolis.” The implication was that Davis was the second on a hit list of activists. Davis told the caller he was calling the police, but the man replied: “It won’t do any good to call the police . . . it’ll be too late when it goes off.”

Police searched the house and found nothing. But the calls continued. On Tuesday, Davis took the phone off the hook at 2 A.M. so the family could sleep. Letters arrived as well full of “unbelievable filth, ugly statements,” and intimate knowledge of his larger civil rights work.

Davis stated vaguely that he was required to take “protective measures” to protect his family. The rabbi did not expound at the time, but later his children recalled that they had a “babysitter” who carried a .45-caliber revolver under his jacket. From his statements to the press, it seems the rabbi was most hurt that the threats were possibly coming from fellow Hoosiers. He told the Jewish Post:

Monday night my life was threatened. Not in Selma. Not in Montgomery. Not in Atlanta. In Indianapolis.

“The Time Has Come to Worship with Our Lives”

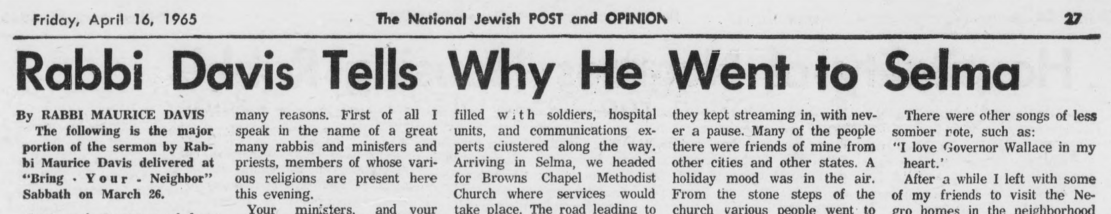

Like King, Davis did not dwell on the darkness of humanity but used it as a chance to shine a light of hope on the potential of his fellow man. Just days after the threats on his family, the Jewish Post published a section of a sermon in which Davis explained why he felt called to join King in Selma. Davis stated that many people had asked him why he went. And he had trouble at first finding the right words. He liked the Christian term of “witnessing,” that is, seeing God in an event. He also liked the Hebrew term that Rabbi Abraham Herschel, who was also at Selma used: “kiddush ha-Shem,” that is, sanctifying God’s name. But in his personable manner, he ended up giving a simpler explanation to the Post:

I know now what I was doing in Selma, Alabama. I was worshiping God. I was doing it on U.S. 80, along with 6,000 others who were doing precisely the same thing, in 6,000 different ways.

He called others to join him. He referred to injustices that needed to still be overcome in order to unite all of humanity as a “brotherhood postponed” and tasked his followers with making sure that while such unity is delayed, it is not destroyed. The way to achieve justice was not only to pray in the traditional way, but also with actions. He wrote:

Brotherhood postponed. The time has come, and it has been a long time coming. The time has come to worship with our lives as with our lips, in the streets as in the sanctuaries. And we who dare to call God, God, must begin to learn the challenge which that word contains. “One God over all” has to mean “one brotherhood over all.”

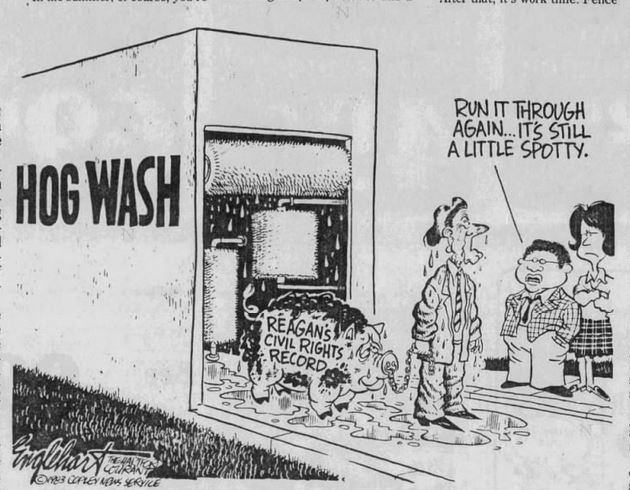

Rabbi Davis continued to work for civil rights in Indianapolis. He was again named honorary chairman of the NAACP. He served as a member of the Mayor’s Commission on Human Rights and on the board of the United Negro College Fund. He was president of the Indianapolis Council of Human Relations and organized the Community Action Against Poverty (sponsored by the City of Indianapolis and the President’s Commission on Equal Opportunity).

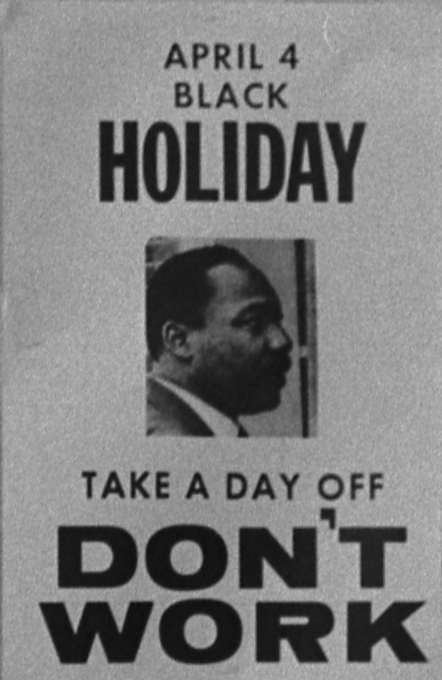

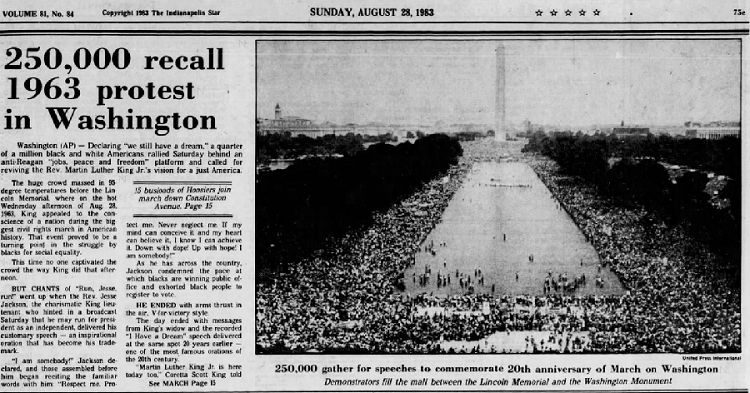

He never forgot his march with King. In 1986, he reflected in the pages of the Jewish Post about a first for the country:

You hear a song, or sniff an aroma, and all of a sudden you are miles and years away . . . It happens, too, with birthdays. January 20 was a very special day. The first national observance of the birthday of Martin Luther King, Jr. I hear them say the words, pronounce the name, and in the twinkling of an eye I am suddenly in Selma, Alabama with some 80,000 other people; Jews, and Protestants, and Catholics, and atheists, and agnostics . . . We were there because of a man whom we admired as much as we loved, and whom he loved as much as we admired. We were there because he was there. And he was there because it was right.

Notes:

The impetus for this story came from Jennie Cohen, Publisher, Jewish Post & Opinion.

Sources for Davis’s report of the march:

Rabbi Maurice Davis, “Rabbi Heschel Finds The Right Word For It,” (Indianapolis) Jewish Post, April 2, 1965, 8, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

Rabbi Maurice Davis, “Rabbi Davis Tells Why He Went to Selma,”(Indianapolis) Jewish Post, April 16, 1965, 22, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

Other sources are linked within the text.

*For more on the disappointment of some civil rights activists with King’s role in the Selma to Montgomery marches see: Deborah Gray White, Mia Bay, and Waldo E. Martin, Jr., eds., Freedom on My Mind: A HIstory of African Americans with Documents (Boston and New York: Bedford/St.Martin’s 2013), 675-6.