See Part IV to learn how the Cleveland Clique leveraged on John Brough to solidify its control of the Bee Line and a route to St. Louis.

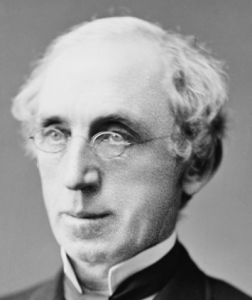

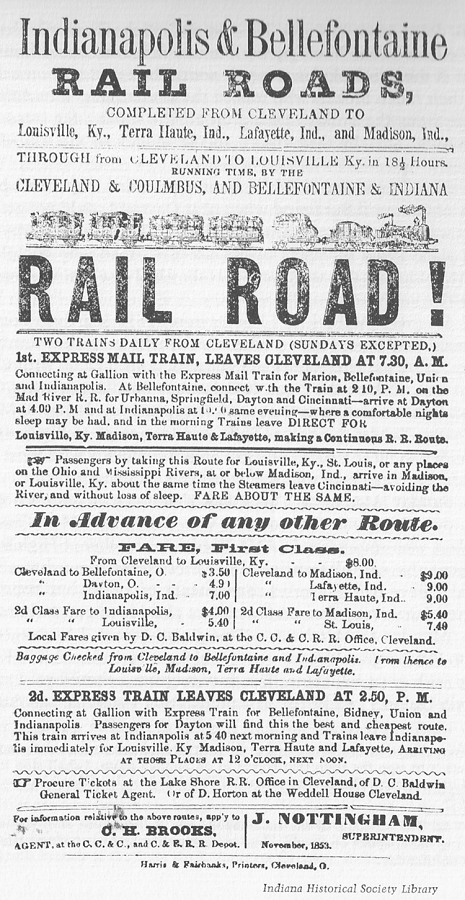

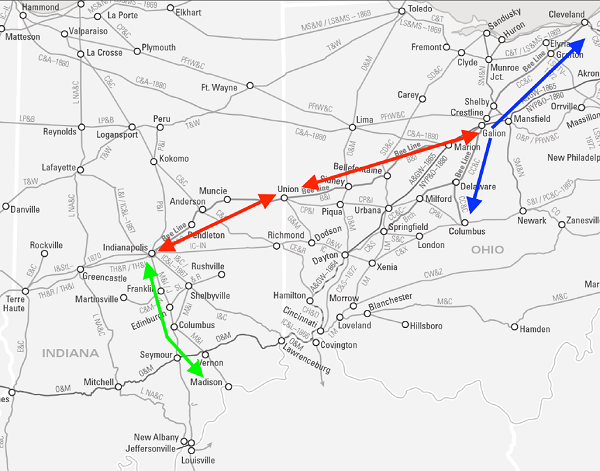

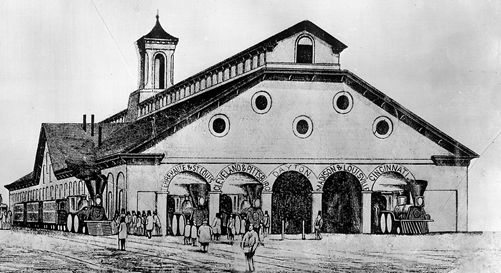

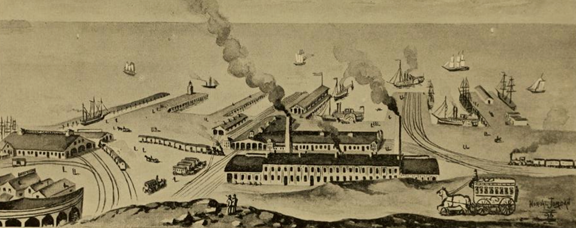

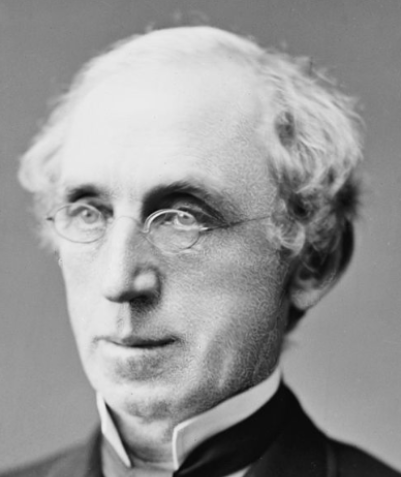

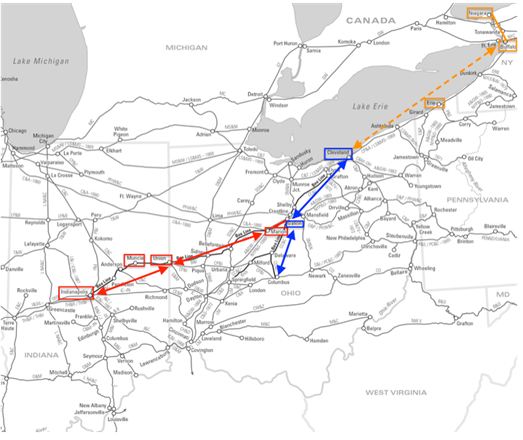

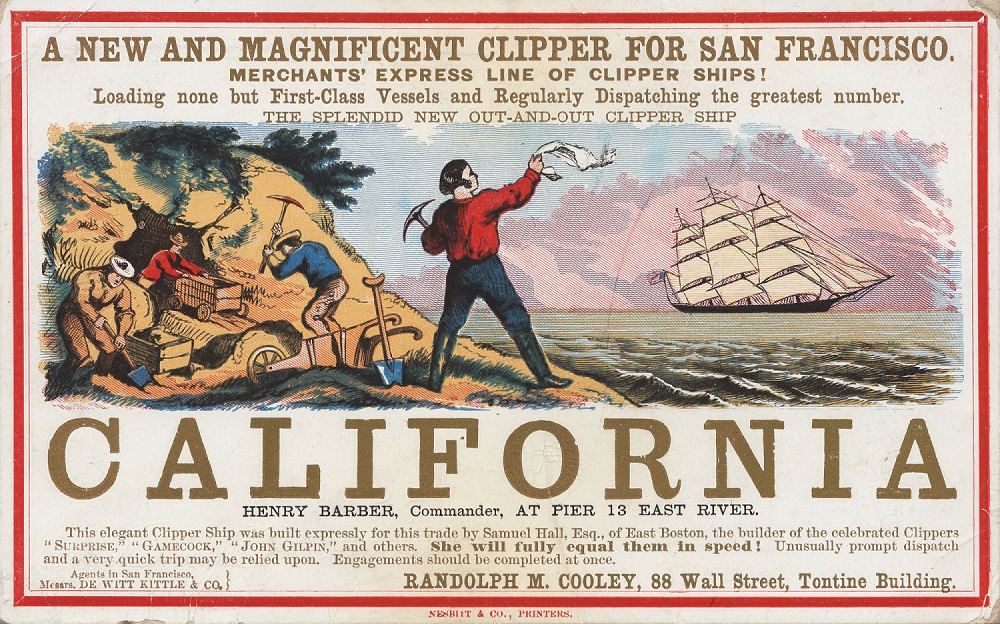

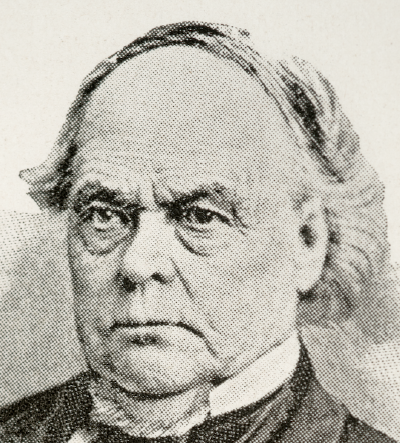

With John Brough’s election to president of the Indianapolis and Bellefontiane Railroad [I&B] on June 30, 1853, the Cleveland Clique cemented its position as the Midwest’s dominant railway cabal. Brough’s dual roles, both there and as president of the Mississippi and Atlantic Railroad (about to initiate construction between Terre Haute and St. Louis), personified the Clique’s reach.

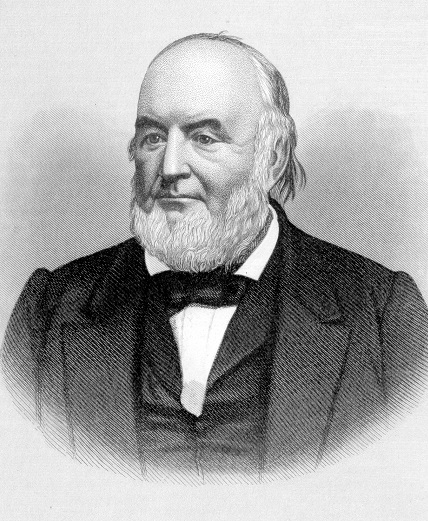

It was also a visible sign of president Henry B Payne’s effectiveness crafting and implementing the Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati Railroad’s [CC&C’s] growth strategy. Now his attention turned to commanding the Bee Line component railroads and a line to St. Louis, both physically and legally. But, the Cleveland Clique’s grasp for control of the Bee Line Railroad would be elusive at best.

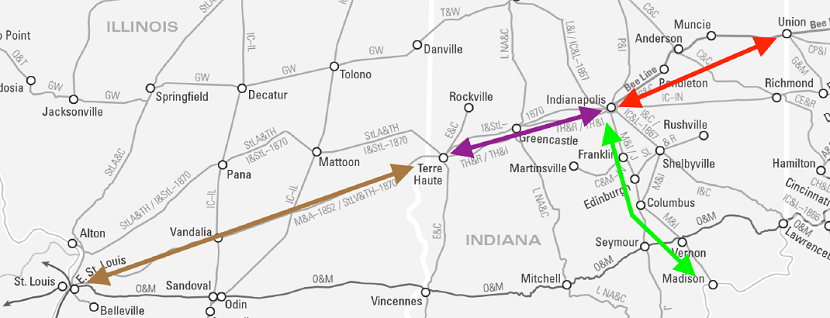

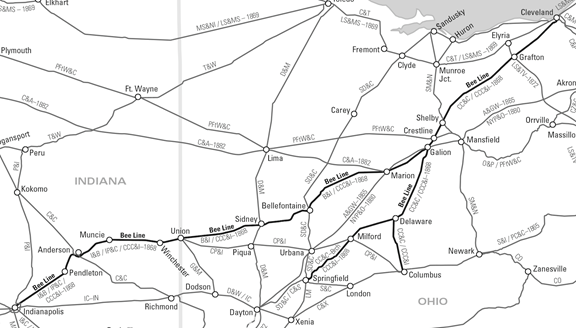

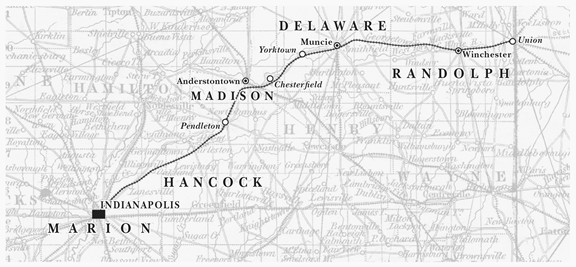

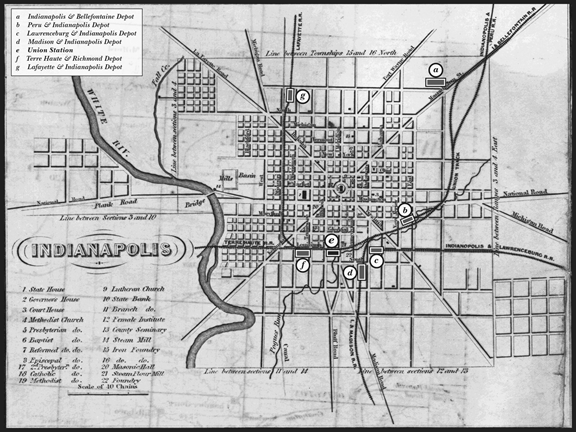

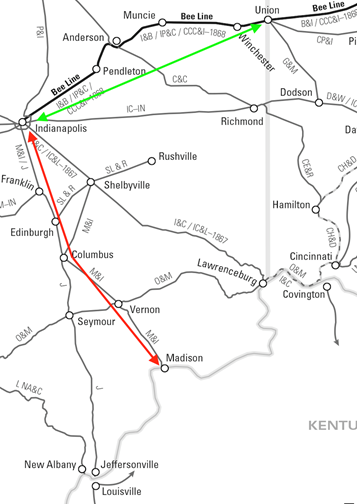

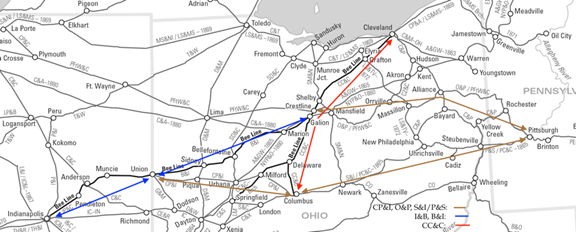

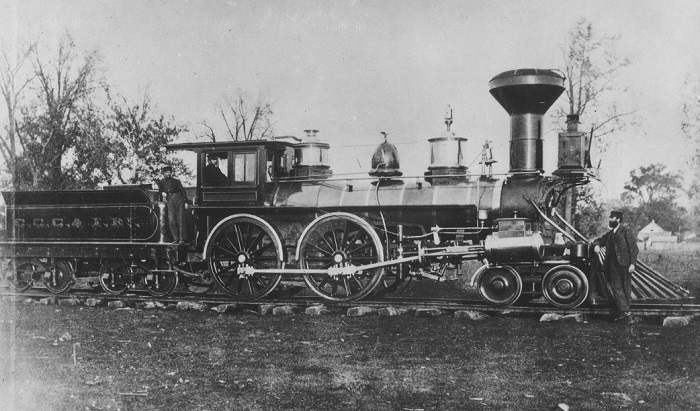

Just prior to Brough’s promotion, the I&B’s Clique-influenced board had resolved to convert its 4’ 8½” ‘standard gauge’ track (lateral dimension between rails) to the 4’ 10” ‘Ohio gauge.’ By law, the Ohio legislature had mandated that all railroads chartered there must be constructed to this dimension. As a result both Ohio legs of the Bee Line, the Bellefontaine and Indiana [B&I] and CC&C, had been built to this dictated standard. The Indiana-chartered I&B’s non-conforming gauge, however, prevented uninterrupted service between Cleveland and Indianapolis.

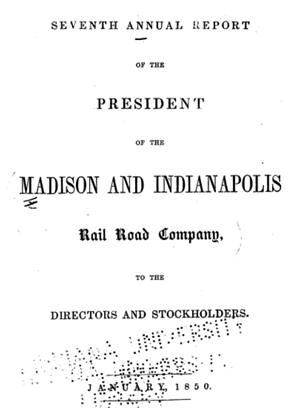

The I&B moved carefully to implement its gauge-change resolution. This was because, in early 1852, former president Oliver H. Smith had come to terms on a through-line agreement with a rail line being built between Columbus OH and Union IN – the Columbus, Piqua and Indiana Railroad [CP&I]. When completed, this important link would provide a connection to lines extending toward Pittsburgh, and on to Philadelphia over one of the growing trunk line giants: the Pennsylvania Railroad.

As part of through-line negotiations to coordinate schedules and share facilities, the CP&I had acceded to Smith’s demand that it petition Ohio’s legislature to build to the I&B’s ‘standard’ gauge. It soon received a legislative exemption and began building. However, the CP&I met financial headwinds almost immediately – most notably from the Pennsylvania Railroad, which failed to meet its guarantee commitment when the company defaulted on construction bonds. Unfortunately, following bankruptcy reorganization, the CP&I would not complete construction to Union until 1859.

From the I&B’s perspective, the CP&I’s financial problems and construction delays seemed insurmountable. In contrast, the temptation to avail itself of lucrative east-west business across the combination of Ohio gauge B&I and CC&C lines proved irresistible. Under cover of a finely crafted resolution to skirt its through-line agreement with the CP&I, the I&B board resolved to lay track using the Ohio gauge as “other circumstances and relations for the welfare of the Road may require.” Under this guise, by the summer of 1853, it had re-laid track between Union and Muncie to the “Ohio gauge”.

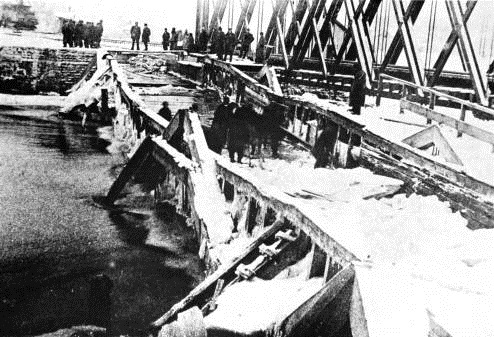

Given this developing situation, the CP&I felt compelled to act. It successfully sought a preliminary injunction to block further track/gauge conversion. The Bee Line was effectively stymied in its effort to achieve a uniform gauge run from Cleveland to Indianapolis. Although the I&B argued the 1852 through-line agreement was silent on the CP&I’s track conversion accord, Smith’s apparent sidebar pact proved compelling to the court. I&B president John Brough, backed by a new board replete with Clique members, was directed to move decisively to resolve the problem in late summer 1853. It proved to be a particularly costly settlement.

Together, all component roads of the Bee Line agreed to guarantee the CP&I’s performance on $400,000 of bonds issued to complete the road to Union. Beyond eventually finding themselves on the hook for this issue, the Bee Line roads would provide another, and then another tranche of funding by the time the CP&I limped into Union in 1859. At least the I&B could now finish its Ohio gauge track conversion between Muncie and Indianapolis. And, under terms of the settlement, the CP&I also re-laid its track to the Ohio gauge.

Winding up the CP&I lawsuit had been a prerequisite to inking a Cleveland Clique-initiated through-line agreement among all Bee Line component roads. The day after securing the CP&I settlement, the Bee Line’s through-line agreement was signed. There were two telling provisions that spoke to the different vantage point of the Cleveland Clique and Hoosier Partisans.

On the one hand, the agreement allowed the B&I and I&B to make “fair and eligible connections and business arrangements . . . to secure . . . their legitimate share of the business between the cities of Philadelphia, Pittsburgh and Indianapolis.” While this clause provided a degree of freedom for the Hoosier Partisans and their Ohio counterpart to step away from their CC&C overseer, the other clause was engineered to reign in these independently minded stepchildren: “The B&I and I&B shall be consolidated at the earliest practicable moment.”

As to the latter clause, it would be easier for the Cleveland Clique to do its bidding if the Hoosier Partisans’ influence was diluted in a newly constituted board. At the same time, combining the two lines could prevent the Partisans from cutting their own agreement with the CP&I to carry traffic back and forth to Columbus and toward Pittsburgh via Union – totally avoiding carriage over the B&I and CC&C. And there was also a second option to reach Pittsburgh, via the Ohio and Pennsylvania Railroad (O&P) – passing near the B&I’s eastern terminus at Galion OH. Still, at the time, the Clique’s consolidation mandate only served to draw the two smaller lines more closely together in their common struggle for independent decision-making. As unfolded for the Cleveland Clique, however, its consolidation directive would not be accomplished easily or quickly.

Squirming under the Clique’s dictate, and recognizing its strategic position as the funnel for rail traffic to and from Indianapolis to either Cleveland (and New York) or Pittsburgh (and Philadelphia), the I&B board served up its own subtle message. Essentially touting its option to bypass Cleveland through separate links to Pittsburgh, Hoosier Partisan David Kilgore proposed a name change “from and after the first day of February 1855. . . . The said Corporation shall be known by the name and style of the ‘Indianapolis, Pittsburgh and Cleveland Railroad Company’ [IP&C].” It was overwhelmingly adopted.

The name change really symbolized much more. The locally controlled and focused I&B railroad era was gone. The newly rechristened road would now test its wings as a regional player—hoping, like a teenager seeking freedom from parental control, to stand apart from the clearly parental CC&C.

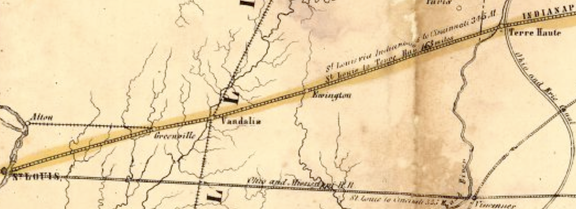

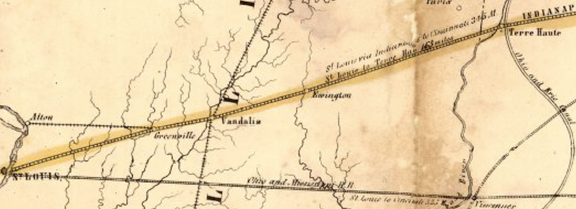

Separately, in 1854, John Brough was ramping up his Mississippi and Atlantic Railroad [M&A] – destined to link Terre Haute and St. Louis. After an arduous legal effort to validate its claim to an Illinois charter, the M&A had prevailed against Chicago and Mississippi River town political interests earlier in the year. However, it would soon be faced with another trumped-up legal challenge and a concerted public relations effort to undermine its viability and management capabilities. Such obstacles were having a detrimental effect on Wall Street investors.

In March 1854 a legal opinion by Abraham Lincoln’s Illinois law office asserted the illegality of the M&A’s corporate existence. Then, a New York newspaper article questioned Brough’s managerial track record at the Madison and Indianapolis Railroad. The investor community was beginning to shy away from the M&A.

Nonetheless, with short-term funding secured, Brough pressed on with the M&A’s building phase. He issued a marketing circular and let contracts for the whole line by May, announcing the line would be completed by the summer of 1856. Brough would spend an increasing amount of time on this effort as 1854 wound down.

By the beginning of 1855 it was becoming clear Brough had the M&A on his mind. At the very least, the M&A’s pivotal role in the Cleveland Clique’s Midwest control strategy virtually mandated Brough’s full-time attention. Rumblings of his imminent departure reached IP&C board members by early February. He resigned as IP&C president on February 15, noting “experience has demonstrated to me that in this event my entire time and attention will be required on that [M&A] line.”

Former I&B director (1852-53) Calvin Fletcher, among Indianapolis’ most prominent civic and business leaders, was elected president in Brough’s stead. Reluctantly thrust into the role, Fletcher noted, upon hearing of his election: “I learned to my regret I was appointed President of the Bellefontaine R.R. Co.”

Fletcher’s reticence to assume the post was understandable, based on his close familiarity with the affairs of the I&B. “I fear their affairs are desperate . . . It needed my character & acquaintance to unravel the mischief of the finances. . . . The president Brouff [Brough] has no influence on the road. All employees eschew his authority & claim that the Superintendent is the man to look to & not the President. The road & its business is [sic] in great confusion.”

Even though Brough was dealing with M&A matters full time beginning in mid-February 1855, the concerted efforts of powerful Chicago and Mississippi River town political interests had swept away investor confidence. James F. D. Lanier, the M&A’s financier through the Wall Street firm that bore his name – Winslow, Lanier & Co. – decided to take desperate action.

On May 20th the M&A board, controlled by Lanier, demoted Brough to Vice President in favor of Chauncey Rose. Rose, founder of the Terre Haute and Richmond Railroad linking Indianapolis with Terre Haute, assumed the presidential mantle. In spite of his impeccable reputation as a railroad executive, Rose’s presence failed to sway the investor community.

John Brough would not live to see the Mississippi and Atlantic Railroad completed to St. Louis. And, more to the point, how would the Cleveland Clique view Brough as their pawn in its broader Midwest railroad control strategy?

Check back for Part VI to learn more about the Hoosier Partisans move for autonomy as the Cleveland Clique tightened its grip on the Bee Line Railroad.

Continue reading “The Cleveland Clique’s Elusive Grasp for Control of the Bee Line Railroad”

![Midwest Railroads Map, circa 1860, showing the Madison and Indianapolis [M&I], Terre Haute and Richmond [TH&R], and component roads of the Bee Line: Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati [CC&C]; Bellefontaine and Indiana [B&I]; Indianapolis and Bellefontaine](http://blog.history.in.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Midwest-Railroads-Map-c1860.png)

![Railroads west from Indiana, including the Terre Haute and Richmond [TH&R], Ohio and Mississippi [O&M], Mississippi and Atlantic [M&A], and St. Louis, Alton and Terre Haute [StLA&TH]](http://blog.history.in.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Railroads-West.png)

![image of The Madison and Indianapolis Railroad [M&I] and involved roads: the Peru and Indianapolis Railroad [P&I], extending north from Indianapolis, and the Mississippi and Atlantic Railroad [M&A], extending west to St. Louis. Terre Haute and Richmond [TH&R]](http://blog.history.in.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/MI.png)