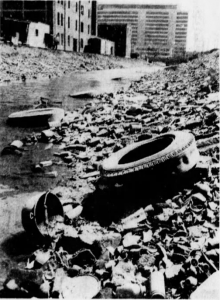

Indianapolis Mayor Richard Lugar proclaimed April 22, 1970 as “a day for contemplation, conversation, and action to halt and reverse the impending crisis of the decay of man’s environment.” Throughout Indiana, Hoosiers acted to raise awareness about the imminent pollution crisis. In addition to general clean up campaigns, panel discussions, and seminars, students built monuments made of trash and participated in marches. Some even donned gas masks or abandoned their cars, all to dramatize the need for citizens to “Give Earth a Chance.”

This was the first Earth Day. Historian Adam Rome describes the day as “the most famous little-known event in modern U.S. history.” He notes it was “bigger by far than any civil rights march or antiwar demonstration or woman’s liberation protest in the 1960s.” A whopping 22 million Americans took part in the first Earth Day. About 1,500 colleges and 10,000 schools, in addition to numerous churches, temples, city parks, and lawns in front of various government and corporate buildings hosted Earth Day activities. The event was so popular that Congress even shut down on Earth Day. About two-thirds of congressmen, both Democrats and Republicans, returned home to speak to their constituents at Earth Day rallies. President Richard Nixon, one of the only major politicians not to make a public speech on Earth Day, even admitted in a press release that he felt “the activities show the concern of people of all walks of life over the dangers to our environment.”

Senator Gaylord Nelson, a Democrat from Wisconsin, conceived Earth Day in 1969. After the Santa Barbara oil spill in January and February of that year, Nelson decided to ignite a mass protest in support of increased environmental action. He had crafted environmental legislation throughout the 1960s, including efforts to ban harmful chemical products, like the pesticide DDT and non-biodegradable detergents. He found few supporters for his initiatives in Congress. However, he surmised many citizens, worried about radioactive fallout, suburban sprawl, and smog, would care. Inspired by anti-war teach-ins in the 1960s, Nelson envisioned a nationwide teach-in event to educate people about pollution and encourage them to take action. If constituents supported environmental regulation, it was reasoned, politicians would follow.

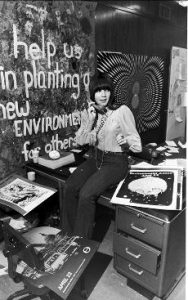

Though Nelson came up with the general premise of Earth Day, he knew the movement would not flourish if he dictated the event. Instead, he announced plans for the teach-in in September 1969 and enlisted the help of Pete McCloskey, a Republican, as co-chair. Soon, individuals all over the country called Nelson’s office, asking for more information. To handle all the activity, Nelson set up a separate organization, Environmental Teach-In Inc., in December 1969. A small staff of twenty-somethings ran the organization. Though Nelson originally created the organization to help local organizers implement ideas and make contacts, Environmental Teach-In mainly became a publicity hub. Community organizers, which often included housewives, students, and scientists started planning Earth Day events before the organization opened.

Thus, the national office spent most of their time fielding calls from journalists to inform them about Earth Day plans in locales across the nation. Organizers planned programs to explore a variety of topics including population growth, pesticide use, nuclear fallout, waste disposal, suburban sprawl, in addition to mainstays like air, water, and land pollution.

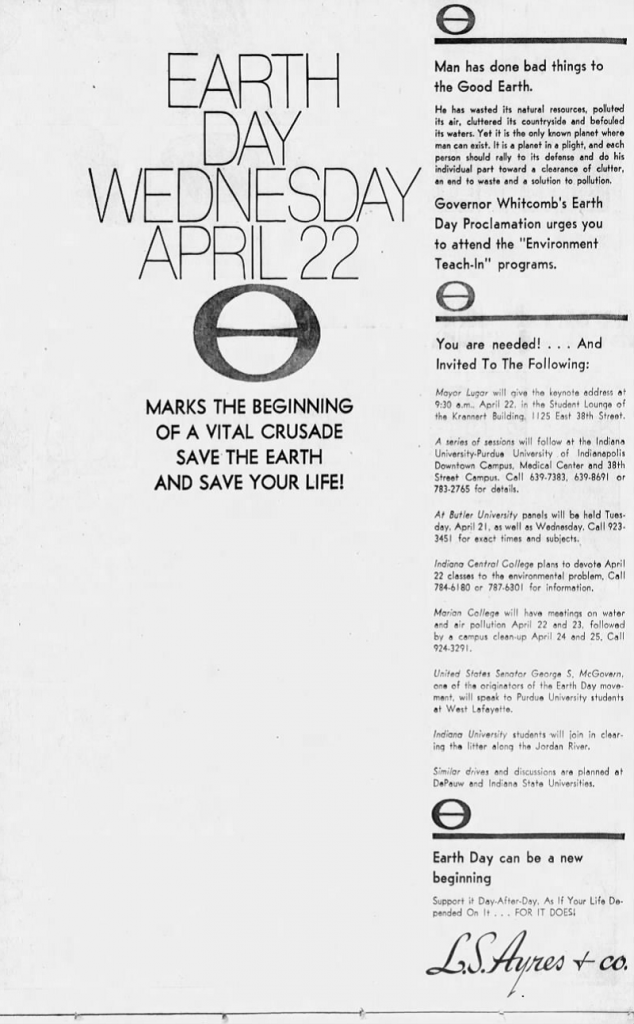

Back in the Hoosier state, Governor Whitcomb issued an executive order endorsing Earth Day activities in Indiana. He wrote “I urge all of our citizens to act responsibly to alleviate the pollution menace to the environment.” In particular, Whitcomb noted:

Our educational institutions have the expertise and capability both to inform us of present dangers resulting from the ways we use our natural resources and to define and develop new technologies and systems needed to abate the pollution problem.

Whitcomb’s emphasis on educational institutions highlighted the primary role students played in Indiana Earth Day. Most of these activities took place at universities, colleges, and schools, which were all open to broader community members. However, it was mostly students, rather than faculty that organized the day’s events. Elizabeth Young, a sophomore at St.-Mary-of-the-Woods College near Terre Haute summarized why young Hoosiers rallied around Earth Day. She told the Indianapolis Star “if the kids our age don’t do something, we won’t live to be the age of our professors.”

Though most activities took place on April 22, students and community members often could attend ecological events at their local university or college throughout the week. Almost all the major secondary education institutions in Indiana sponsored panels, lectures and discussions featuring a variety of speakers, including politicians, scientists, and industry representatives. Senator Nelson even spoke at rallies at IU Bloomington and Notre Dame. Most of the Indiana congressional delegation returned from Washington, D.C. to speak to their constituents. At Purdue, industry representatives from Inland Steel, Eli Lilly, and General Motors participated in a panel discussion. Each talked about the measures their company was taking to abate pollution and answered questions from audience members. Many universities organized tree planting ceremonies or litter clean-up operations along Indiana waterways.

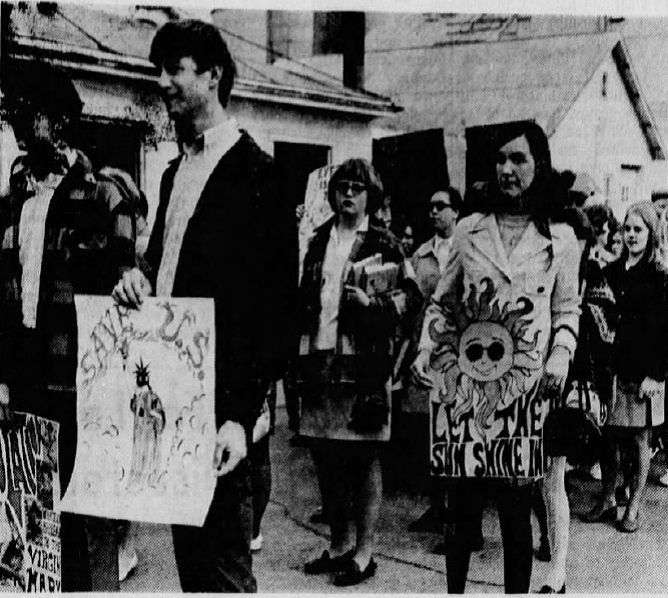

A few students staged more dramatic events to draw attention to environmentalism. At Ball State University, students constructed a pile of cans and bottles they collected from Muncie residents and created a “non-disposable, non-returnable monument” on the terrace of the Art Building. The monument symbolized junk, which students perceived as one of America’s primary pollution problems. At Purdue, students picked up litter along the Wabash River and displayed it all in front of the Lafayette courthouse for the public and local government representatives to see. DePauw students sponsored bus tours for community members to take throughout Greencastle, which would showcase Putnam County’s dirtiest and cleanest spots, including a junkyard, a pig feed next to a stream, homes designed specially to preserve the terrain, and an industrial plant featuring the latest pollution control measures. Others specifically tackled air pollution issues. Tri-State College in Angola (now Trine University), initiated a campaign urging students and faculty to leave their cars at home and walk to campus. One DePauw student rode a horse to campus bearing the sign “Ban the automobile.” DePauw also put an electric car on display.

Numerous younger students participated as well. Schools received packets detailing available speakers, films, materials, and suggested programs and activities to coordinate for Earth Day activities. Elementary school students picked up litter and participated in art and essay contests about environmental issues. In Portland, elementary students started a “Be a Pollution Policeman” campaign and created posters advising community members to report polluters that they later put up all over town.

North Central High School students in Indianapolis hosted an Earth Day program filled with speakers, seminars, and films. Students created a pollution themed skit and a collage made with all the litter they collected in the area. Several student musicians played music alongside a slide show of photographs of local pollution. At Southport High School, a group of students all wore gasmasks to class to highlight air pollution. Logansport physics students marched through town sporting posters and signs. At Edinburgh, high school students even produced a television program “Project Earth Day,” aired on a Columbus news station that examined water, air, and land pollution in the area.

Despite the major successes of Earth Day, a lot of issues remained unsolved. Whitney M. Young Jr. addressed the major deficit of the Earth Day celebration and of the ensuing environmental movement, in the Indianapolis Recorder in 1970: Earth Day programs often failed to incorporate race or class into the problem of pollution. Though pollution was finally spreading to the suburbs, people of color had often been forced to live and work in places containing dangerous pollutants for years through zoning ordinances and prejudiced real estate practices. He noted, “I get the uneasy feeling that some people who have suddenly discovered the pollution issue embrace it because its basic concern is improving middle class life.” He concluded:

The choice isn’t between the physical environment and the human. Both go hand in hand, and the widespread concern with pollution must be joined by a similar concern for wiping out the pollutants of racism and poverty.

Earth Day did, however, inspire landmark legislation and institutions to address pollution. In later years, some environmental justice organizations tackled the issues Young brought up. Adam Rome notes Earth Day “inspired the formation of lobbying groups, recycling centers, and environmental studies programs. Earth Day also turned thousands of participants into committed environmentalists.” Before Earth Day, Americans addressed environmental issues in disjointed ways. Old conservation groups from the Progressive era focused mainly on wilderness preservation. Other groups focused on single issue campaigns, like air pollution. Earth Day pushed numerous related environmental concerns into one platform and provided a space for concerned citizens to come together and decide how America should fight the environmental crisis of the 1970s. The constituent support Earth Day garnered encouraged Congress to enact a swell of landmark environmental legislation after Earth Day, including the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency in December 1970, the Clean Air Act amendments of 1970, the Clean Water Act in 1972, and the Endangered Species Act in 1973.

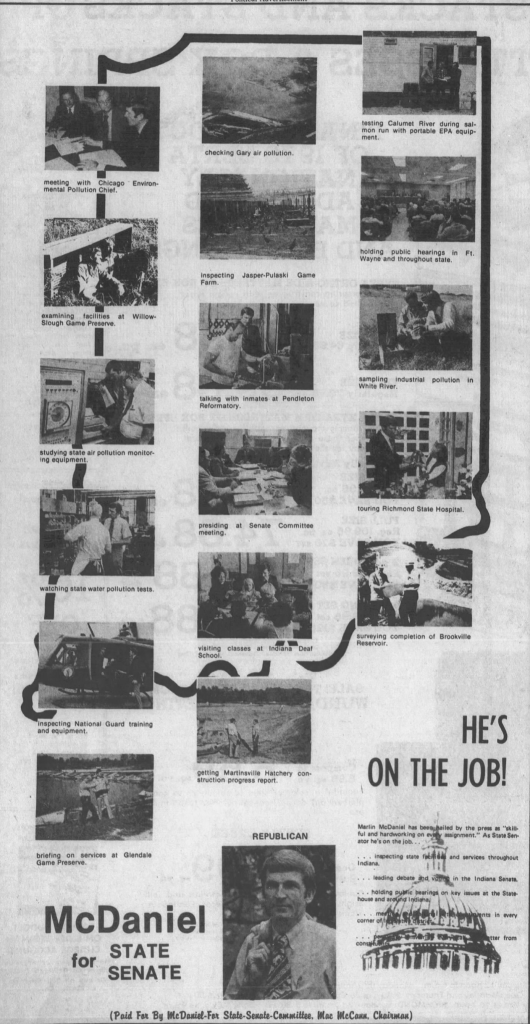

Indiana politicians also dedicated more of their time to environmental issues after Earth Day. Governor Whitcomb started “Operation Cleansweep” in May 1970, a massive campaign to clean up polluted and littered landscapes across the state. On the first anniversary of Earth Day in 1971, Mayor Lugar launched Indianapolis’s first recycling program to collect cardboard and metal. Indiana also became the first state in the nation to ban phosphate detergents, which scientists discovered as a major polluter of waterways, in 1971. Additionally, more Hoosiers joined or formed environmental organizations to make sure the state government stayed on top of environmental regulation. For example, the Indiana Eco-Coalition formed in 1971 to serve as an umbrella organization to represent the majority of Indiana’s environmental activist groups and provide information on impending environmental legislation.

Clearly, when people shouted “Give Earth a Chance,” it worked.