A Royal Lunch

Moy Kee was undoubtedly “One of the happiest persons in Indianapolis,” according to The Indianapolis News on May 26, 1904. It appears he was also one of the busiest. Moy Kee and his wife, Chin Fung, were preparing to host royalty. Chinese Prince Pu Lun, rumored heir to the Qing Dynasty imperial throne, was visiting America and agreed to have lunch at Moy Kee’s chop suey restaurant in Indianapolis before he departed from the city. According to news reports, Moy Kee’s house was “thrown into raptures over the honor,” as he, his wife, and servants frantically cleaned the restaurant, prepared their best ingredients, and laid out the finest decorations they had for the prince.

On May 27 at 1 o’clock the prince, Indianapolis Mayor John Holtzman, business tycoon and future Senator William Fortune, esteemed poet James Whitcomb Riley, and other notable guests bore witness to Moy Kee’s late night labors. Outside of the restaurant, traditional Chinese lamps were strung with brightly colored ribbons. The American and Chinese flag flew side by side. A May 28 Indianapolis News article described the interior of the building as:

Oriental rugs were spread from the street to a teakwood table, where were placed two beautiful inlaid chairs covered with crimson satin draperies. The carved table stood on beautiful rugs, and upon it were placed burning incense, chop suey, and Chinese wine.

The first course consisted of the restaurant’s signature chop suey paired with American beer. Ice cream and tea were served for the second course, and the luncheon ended with traditional Chinese wine. Upon departing, Chin Fung presented the prince with a hand-knitted scarf and Moy Kee gifted him a bouquet of flowers. The prince gave the Moy family a silk scarf bearing his name and, upon leaving, informed Moy Kee that he would elevate him to Mandarin of the Fifth Rank, a prestigious Chinese status that would allow Moy to entertain and be entertained by royalty, wear special regalia, and hold a certificate denoting his prestige. This honor was monumental for a Chinese immigrant like Moy and a status that many of the wealthiest men in China failed to achieve.

As discussed in part one of this series, Moy Kee was granted an American citizenship in 1897 and then rose to prominence in Indianapolis by becoming the unofficial leader for the small Chinese community in the city. Part two follows the rest of Moy’s life as he entertained Prince Pu Lun, achieved even more wealth and status in both China and America, and then struggled to retain that prominence later in life.

Prince Pu Lun and the St. Louis World Exposition

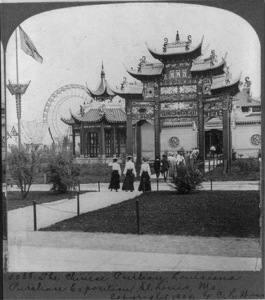

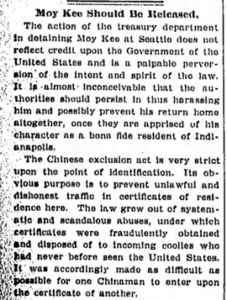

During the early 1900s the Qing dynasty’s isolationist policies started thawing, and the nation began entering foreign affairs. This new administrative goal was evident when the government opted to not only participate in the St. Louis World’s Fair (China had declined to participate in the Chicago World Fair eleven years prior) but to appoint the nephew of the emperor, Prince Pu Lun, as the official fair commissioner. Pu Lun’s visit generated positive media coverage that helped warm American attitudes towards the Chinese. Domestically, Americans were fearful of “The Yellow Peril” of Chinese immigrants, whom many believed were impossible to assimilate into “The American Melting Pot.” Some accused the Chinese of flooding the labor market and stealing jobs from white Americans. Abroad, Americans believed the Chinese Empire was backwards and culturally stagnant. Rising racist attitudes towards the Chinese culminated in President Chester A. Arthur signing the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882.

Prince Pu Lun in Indianapolis

Prince Pu Lun arrived at Union Station in Indianapolis on May 18 for a ten-day tour of the Hoosier State. His schedule moved at a breakneck pace, with the press breathlessly reporting on his every move. Some highlights of the visit include the prince visiting the Columbia Club, meeting James Whitcomb Riley, touring Purdue University, and attending a commencement at May Wright Sewall’s Classical School for Girls. Moy Kee had been anticipating Pu Lun’s visit for months now and tried to be as involved as possible. He was among the crowd of Chinese gathered to welcome the prince at Union Station. Afterwards, Moy attended a welcome reception held at the Statehouse where he presented the prince with a bouquet. Moy Kee and Chin Fung again met with the prince two days later, this time at the Local Council of Women’s reception. Technically, only Chin Fung was invited to this reception, but Moy Kee insisted on going, stating his wife needed an “escort.” Afterwards, Moy was granted a short audience with the Pu Lun at his hotel. While the specifics of the meeting were not discussed, the prince was likely interested in seeing how Moy Kee and other immigrants were faring in Indianapolis and may have developed a business relationship with Moy Kee.

The next few days there seems to have been little interaction between Moy and Prince Pu Lun as he traveled to Lafayette to tour the campus of Purdue University. During that time, Moy lobbied for the opportunity to host Prince Pu Lun one last time before his departure. He begged William Fortune that the prince grant him one more audience and “that he might stay for five minutes, a minute, or the least fraction of a minute.” Upon hearing the request, the prince decided to not only call upon Moy but to visit his chop suey restaurant and lunch with the Moy family.

The lunch was brief but pleasant and provided Moy with a critical opportunity to leave a lasting impression on Prince Pu Lun and his Hoosier hosts. The three-course meal combined American cuisine such as ice cream and beer with traditional Chinese chop suey and freshly brewed tea. This interesting fusion of food and drink reflected Moy’s unique background as both a Chinese and American citizen and ensured all the guests received a dish or drink that they enjoyed. When the Prince recommended Moy Kee for the fifth rank, it seems that Moy was genuinely surprised and delighted. He profusely thanked the prince for the honor and bowed multiple times to show his appreciation. After exchanging gifts and pleasantries, Prince Pu Lun departed the restaurant. He climbed the Soldiers and Sailors monument and said his goodbyes to his hosts Mayor Holtzman and William Fortune before traveling to Union Station and departing for Buffalo, New York.

Moy Kee is Named Mayor of Indianapolis’s Chinatown

While the prince’s visit lasted only ten days, it had a great impact on the Indianapolis’ Chinese community and Moy Kee. On the prince’s return trip from New York, he briefly stopped at Union Station. Moy Kee waited for his arrival and presented him with a handcrafted emblem he had commissioned as a thank you for granting him an audience. The emblem was a jeweled American flag with a Chinese dragon styled on its face. In the dragons’ fangs, it held a three-carat diamond. All in all, the emblem was rumored to cost 700 dollars, the equivalent of nearly $20,000 today. Newspapers reported that the prince and Moy chatted like “old friends” at the station. According to the Indianapolis News, in late July, Prince Pu Lun fulfilled his promise of elevating Moy Kee to fifth rank. Moy received a blue-bordered certificate embossed with the imperial seal that read:

This is to certify that, by the order of his imperial highness, Prince Pu Lun, Moy Kee, Indianapolis, ind., U. S. A., is hereby appointed mayor of Chinese. He is directed to attend to all the business of our people truthfully, honorably and honestly. To Moy Kee is hereby given the fifth rank and right to wear the crystal button.

The certificate is the first time Moy Kee is referred to as “Mayor” of the Chinese population in Indianapolis. While the term “Mayor of the Chinese” was an unofficial title that held no political power, the Chinese government often named a prominent leader of an immigrant community as the mayor. These leaders were expected to represent the Chinese people and act as an informal liaison between the Chinese government and American government. For the Chinese people itself, it also solidified the social hierarchy to be followed. For Moy, the title “Mayor” recognized his leadership within the American community while the fifth rank designation solidified his significance within Chinese society.

From that point onward, Moy constantly referenced his ties to Prince Pu Lun and his fifth rank designation. Later that fall, Moy attended the St. Louis Fair and spoke at the China Pavilion while publicly donning the robes and regalia that denoted him as fifth rank. At home, Moy conducted pricy home renovations and began ordering lavish items to decorate his home in a fashion that “befit his gentleman rank.” In 1906, Moy Kee traveled to Washington, D.C. where he met with Indiana Senator Charles Fairbanks. He even had an audience with President Theodore Roosevelt. Without a doubt, in the immediate years after Prince Pu Lun’s visit, Moy had reached the zenith of his power. He had successfully clawed his way up the social ladder of both Chinese and American society. Now, a much more difficult task presented itself to Moy Kee, retaining his hard-earned influence and social standing.

Moy Kee’s Fall from Prominence

Moy Kee once again received an imperial letter in October of 1907, but, unlike the last imperial letter Moy received, this one contained unwelcome news. It informed Moy that he had been stripped of his rank as Mandarin of the Fifth Degree and his status as the mayor of Indianapolis’ Chinese had been revoked. The succinct announcement refused to elaborate on why Moy’s statuses had been rescinded and led to widespread speculation. Moy believed fellow Chinese in Indianapolis engineered his downfall. This paranoia stemmed from his role in 1902 as an interpreter in the murder trial of Doc Lung, a local Chinese laundryman. Some accused Moy of siding with the police and courts over the Chinese community. Newspapers speculated that the revocation was caused by accusations that Moy had raised relief funds for Chinese earthquake victims but had never donated them. It may have also been a result of shifting political powers in an increasingly unstable Chinese royal dynasty, which would collapse in 1911. Regardless of the reason, Moy was unable to protest the Chinese delegation’s decision. He and his wife had already arranged to set sail for Canton, China on October 21st to visit family and friends in a year-long visit. They decided to proceed with their trip, but Moy publicly expressed his disappointment that he would not be returning to China with his fifth rank status.

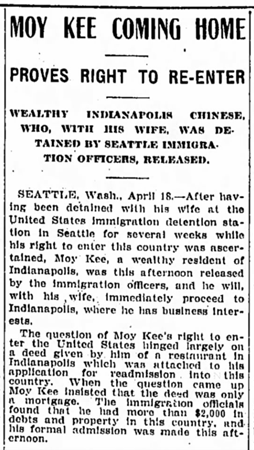

A year later, in March of 1909, Moy Kee and Chin Fung returned to America. However, after landing in Tacoma, Washington Moy’s citizenship papers were not accepted, and the couple was taken into custody. The Moy family was arrested because the Chinese Exclusion Act forbade Chinese from entering the country and officers believed Moy’s citizenship papers were not legitimate. During questioning by immigration officers, Moy allegedly declared himself to be a “citizen of Indianapolis, the best city in the country.” The couple was detained for over a month in deplorable conditions. Several times, it seemed that they were going to be deported back to China. Multiple figures in the Indianapolis community vouched for the Moy family’s right to reenter and the Indianapolis Star published several scathing stories criticizing the Seattle immigration office for detaining him despite his citizenship. Finally, on April 18, Moy was released and allowed to return to Indiana where he resumed operation of his chop suey restaurant. The month they spent in detention was a bleak reminder that outside of Indianapolis, their family and other Chinese were not welcome in America.

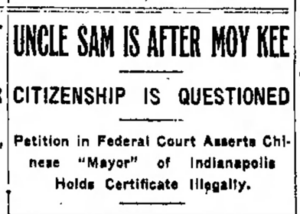

More trials awaited the Moy family in 1911. This time the bearer of bad news was the federal government. On August 4, Moy was informed that a petition asking for his citizenship to be revoked by the federal courts had been filed on the basis of his naturalization being awarded “wrongfully and without right,” fourteen years prior. According to an August 5 Indianapolis Star when Moy heard this news in his restaurant, he:

Dropped a dish which he had had in his hand and stared for several moments in silence. A look of anguish clouded his customarily smiling countenance. It was one of the saddest moments of his life. It was with difficulty that he spoke. ‘It’s no use to buck Uncle Sam… I’ll not fight it. If they don’t want me to be an American… it’s no use to fight them- I haven’t enough money to do that, even if I wanted to. It’s too bad.’ Then Moy fell silent. He would say no more.

Moy Kee was over sixty-three years old and the dogged vigor and determination to retain his citizenship, something he had lobbied tirelessly for as a young man, had faded. However, the Indianapolis community still stood by the former Chinese mayor, with local newspapers universally criticizing the investigation. Mayor Samuel L. Shank even wrote a letter to President Taft imploring him to allow Moy to retain his citizenship, calling him one of Indianapolis’s finest citizens. The letter fell on deaf ears and on October 9, 1911, Moy lost his beloved American citizenship.

Moy was not deported by the federal government and allowed to live and work in Indianapolis. While he was generally treated the same by Indianapolis residents, he now could no longer claim equal footing with Americans and was at constant risk for deportation. Symbolically, the federal courts had sent a message that there would be no exceptions to the Chinese Exclusion Act and, subsequently, that all Chinese remained unwelcome in America. For the next three years, Moy lived his life in Indianapolis much the same as he had lived before. He operated his restaurant, threw Chinese New Year parties, and remained a cornerstone of Indianapolis’ Chinese community. Newspapers noted that Moy still viewed himself as an American and outside his restaurant still hung a Chinese and an American flag, flying side by side.

In January of 1914, while eating dinner, Moy Ah Kee suffered a sudden heart attack and died on the floor of his Washington Street restaurant, the same place where he had hosted Prince Pu Lun seven years earlier. After putting the family’s affairs in order, the widowed Chin Fung set sail to China with Moy’s body, where she intended to bury him with his ancestors and live the remainder of her life. In his obituary, The Indianapolis Star recounted his life story and noted that he was one of the most prominent businessmen in the state with an estimated fortune of $25,000 (over $722,000 in today’s currency). The Star ended a two-decade partnership with the Chinese businessman by stating: “He was regarded as the prominent local source of information on questions relating to Chinese affairs and often was consulted by officials and newspaper writers of the city, among whom he had many friends.”

Conclusion

In 1943, twenty-six years after Moy Kee’s death, the United States repealed the Chinese Exclusion Act to signify diplomatic ties between the US and China during World War Two. However, the new immigration quota enacted allowed only 105 Chinese immigrants per year. The strict immigration quotas remained in place for Chinese until 1965, when the United States enacted the Immigration and Nationality Act that ended ethnic quotas. Instead, the United States began admitting immigrants based on education, employable skill, or the need for asylum. While this prevents blanket bans against entire ethnic groups or nationalities, these new admission standards create significant barriers for working-class immigrants, and American immigration policy remains hotly debated today.

This revised protocol led to an influx of highly educated and skilled Asians and, with this new population, the stereotype of Asians as the “model minority” arose. This characterization of East Asians, which generalizes them as smart, affluent, and hard-working, would have been unrecognizable to Moy Kee and other Chinese immigrants in the 1800s. While on the surface this stereotype is complimentary, it is still a negative and egregious overgeneralization of a diverse ethnic group and masks the sordid history of discrimination against Chinese people by the United States. After a series of Asian hate crimes in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the nation is once again grappling with the impact of both modern and historical discrimination against people of Asian and Pacific Islander descent.

Moy Kee’s life serves as a staunch reminder of some of those inequities and how they consumed the entirety of America, not just the bio-coastal states, for well over a century. An entrepreneur and businessman, Moy rose to prominence socially and fiscally in a way that was unimaginable to most immigrants. His life reached its zenith when he was granted the Chinese title of the fifth rank while also maintaining dual Chinese American citizenship. However, as Moy Kee put it himself, there was no use “fighting Uncle Sam” and he was stripped of both his fifth rank and citizenship late in life, a sad reflection of America’s political and social landscape during his life.

Ultimately, Moy Kee’s life provides an insightful window into the lives of Chinese immigrants in the Indianapolis community and showcases a story of resilience and fortitude in the face of insurmountable odds. As America continues to confront its tragic past and conflicted present regarding its treatment of Asian Americans and immigrants as whole, hopefully the national dialogue remembers the story of Moy Kee and thousands of other Chinese immigrants who were wrongly barred entry to America and denied citizenship due to their race and the prejudiced stereotypes that were perpetuated about their people.