A Disturbing Question

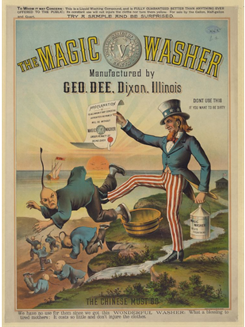

In 1901, The San Francisco Call urged the renewal of The Chinese Exclusion Act, the only legislation in American history that wholly banned the immigration of a specific ethnic group. The Call emphatically supported this renewal stating that America ought to be doing everything in its power to “prevent the threatened invasion of Mongol hordes.” Sentiments like this were not uncommon. Racist cartoons, articles calling for Congress to defend America from the “Yellow Peril,” and state conventions or resolutions urging the renewal of the Exclusion Act were a dime a dozen in 1901. That same year, The Indianapolis News ran a very different story. This article criticized the Exclusion Act and threw its support behind Moy Kee, a Chinese immigrant and resident of Indianapolis, as he sought a federal government job, from which Chinese immigrants had been barred. The Indianapolis News noted on March 8, 1901:

Moy Jin Kee, Chinese Merchant and caterer at 211 Indiana avenue, is about to renew with the Government a disturbing question as to the effect of the Garry alien law passed by Congress . . . He has lived in this country over forty years, speaks excellent English . . . he was brought to this country from Canton when a mere child . . . Mr. Moy is an earnest seeker after appointment.

While Moy Kee never received a federal appointment, the Indianapolis community would prove to be staunch supporters of Moy Kee. The Marion County Circuit Court granted Moy his citizenship when federal law forbade it. Newspapers sold Moy ad space for his chop suey restaurant and frequently approached him for interviews. Later, when his citizenship was challenged by the federal government, Indianapolis Mayor Samuel L. Shank personally wrote a letter to President Taft defending Moy as “universally regarded as being one of the city’s best citizens.” These actions across the Indianapolis community demonstrate the level of prominence Moy Kee had attained in Indianapolis during a time when anti-Chinese attitudes in America were at an all-time high. This blog will outline the arduous path Moy traveled to obtain his American citizenship and how he used his personal assets to carve out a place in both the Chinese immigrant and Indianapolis community.

Moy Kee Seeks American Citizenship

Moy Kee immigrated to the United States in the 1850’s as a young boy from Guangdong Province in China. Like many Chinese immigrants of the time, his family came to America seeking work and an escape from the political turmoil plaguing China. However, rather than wishing to build wealth and return to China in calmer times like most Chinese immigrants, Moy wanted to stay in America for the rest of his life. Not only that, but he also wanted to become an American citizen. To better assimilate with his new home, Moy converted to Christianity and attained fluency in English. In 1878 he moved to New York and ran a business selling imported Chinese goods. He also became involved in Christian ministry and began proselytizing the New York Chinese community. However, Moy was accused of stealing from one of his employers and jailed. While there are no records of a trial, Moy decided to shed his tarnished reputation by seeking a fresh start in Chicago. Critically, before Moy left New York he filed a declaration of intent to become an American citizen, the first step of the naturalization process. This would prove to be a watershed moment in Moy’s quest for citizenship because two years later the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was signed into law by President Chester A. Arthur.

The Chinese Exclusion Act is notably the only legislation in American history that provides an absolute ban on immigration against a specific ethnic group. It instated a ten-year ban on Chinese immigration, enacted severe restrictions on current immigrants – now at constant risk for deportation – and effectively blocked all Chinese from American citizenship. In 1892 the Exclusion Act was renewed for another decade via the Geary Act and then in 1902 it would become permanent legislation.

The Chinese Exclusion Act and the anti-Chinese sentiments that spurred it would become a constant source of disruption and conflict in Moy Kee and thousands of other Chinese immigrants’ lives. In Chicago, Moy Kee opened a Chinese tea shop and began his protracted battle for his citizenship. In the community, he helped organize the Chicago Chinese Club, a political group aimed at bettering the lives of the Chicago Chinese and protesting the Chinese Exclusion Act. Individually, Moy spent years lobbying the local courts, arguing that because he filed his intent to become a citizen two years before the ratification of the Exclusion Act, the law did not apply to him, and therefore he was eligible for citizenship. Year after year the Chicago courts rejected his argument and Moy remained, legally at least, a stranger in his own home.

Moy’s legal luck changed in 1897 when he and his wife moved to Indianapolis, setting up a litmus test of Indiana’s proverbial “Hoosier Hospitality.” In Moy’s case at least, Hoosier Hospitality rang true and on October 18th, 1897, eighteen years after Moy had begun the naturalization process (By comparison, the naturalization process today lasts on average 12-16 months), the Marion County Court granted him his coveted American citizenship.

Moy Kee Climbs the Social Ladder in Indianapolis

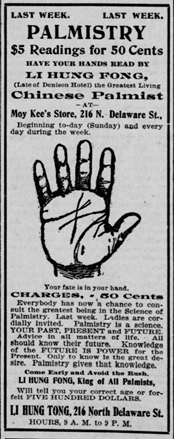

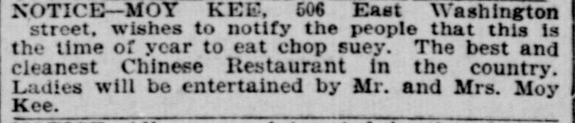

While Moy Kee may have obtained his citizenship, his work to be accepted by the Indianapolis community was far from complete. Moy settled down in Indy and eventually opened a Chop Suey and Chinese restaurant at 506 East Washington Street. A sign hung outside his restaurant advertising it as “Moy Kee & Co. Chinese Restaurant,” though the papers frequently referred to it as “Mr. Moy’s Chop Suey House.” He intentionally began inserting himself into as many community functions as possible. There are news articles of Moy hosting large Chinese New Year’s parties, playing Chinese instruments at school functions, inviting local politicians to dine at his restaurant, and selling Chinese palm readings for fifty cents. He even planned to open a Chinese language school, though his idea never came to fruition. Entrepreneurial and outgoing, it seems Moy was willing to try everything at least once.

However, as diverse his activities may have seemed they always shared one common thread. All his actions served to further integrate himself into the Indianapolis community and they all hearkened back to his Chinese roots. In this way, Moy used his heritage as a source of novelty and entertainment for the community. Rather than divorce himself from his culture to “mix in” with the great American Melting Pot, he successfully mobilized his Chinese heritage as a vehicle for his accumulation of wealth and social standing in Indianapolis.

Compared to coastal states like Californian, Indianapolis had a small Chinese immigrant population. The 1910 Census estimates that only 273 Chinese lived in Indiana and, in Indianapolis specifically, the Indianapolis News, reported that the Chinese had a “local colony” of about 40 or so immigrants including Moy Kee. The miniscule population of Chinese immigrants in Indianapolis may have contributed to the city’s relative receptivity to the Chinese when compared to states with significant Chinese communities. Furthermore, the low population explains why Indianapolis never developed a centralized locale or “Chinatown” like New York or Chicago did. There simply were not enough Chinese to do so. Instead, the Chinese immigrants clustered around Indiana Avenue, a historic strip of downtown Indianapolis that was known primarily for housing a vibrant African American community. The decentralized nature of the Chinese community provided Moy Kee with the perfect opportunity to rise to power as the Chinese representative to the city and, in doing so, ensure his place in Indianapolis.

Moy Kee both stood for and apart from the Indianapolis Chinese community. This allowed him to rise to prominence in a fashion unfathomable for the average immigrant. For one, the census records list his wife Chin Fung as being the only Chinese woman to live in Indianapolis in the late 1890’s. Compared to other Chinese men who had to balance both work and domestic duties alone, Moy Kee’s wife helped him around the restaurant, entertaining guests and managing the house when Moy was away. Chin Fung’s extra support allowed Moy to be more experimental as he could divert attention to other tasks besides running his restaurant and house. Furthermore, as the only Chinese woman in the city, Chin Fung received attention from the news media, who described her as a graceful and poised woman and were fascinated by her traditionally bound feet, which caused a peculiar gait.

Second, Moy Kee separated himself from other Chinese in the community by owning a successful restaurant. He was wealthier than the average Hoosier and even employed his own servants to help run the household and restaurant. This contrasted with most Chinese men, who were stymied by language barriers and Sinophobia and, as a result, toiled in stagnant, low-level service industries such as laundry, cleaning, or construction. With paltry salaries that almost all were sent back to impoverished family in China, this left little wealth for the average Chinese immigrant and, as a result, they often lived hovering just above the poverty line. In contrast, Moy’s wealth allowed him to return home to China fairly frequently and keep in touch with relatives. He even was able to travel to China to marry Chin Fung before bringing her back to America. Moy’s wealth also enabled him to import several Chinese goods for his restaurant including traditional decorations, ebony wood, ivory China table sets, and unusual foods that attracted both Chinese and non-Chinese customers alike.

Moy’s most valuable asset in his rise to prominence was his ability to speak fluent English. This fluency cemented him as the unofficial spokesperson of the Indianapolis Chinese community, and he took full advantage of it. He spent years cultivating a positive relationship with the local newspapers by buying ad space for his restaurant and happily providing interviews and engaging stories about his many endeavors. When reporters wanted to cover a story about the Chinese community, they contacted Moy. This working relationship was a major factor in the divergent coverage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in Indianapolis compared to other cities. Most articles about Moy or the community positively portray the Chinese and avoid fear-mongering headlines about “the oriental wave,” or “yellow peril.” Indianapolis was not immune to xenophobic sentiments (Among other questionable coverage, The Indianapolis Morning Star accused Chinese royalty of visiting America to recruit American soldiers for the imperial army and The Indianapolis Journal often referred to the Chinese as “coolies”) but, compared to newspapers in California or other states, negative rhetoric was relatively muted.

Moy Kee Struggles to Balance His Ambition and the Chinese Community

In 1902, Moy Kee’s ambition to integrate with the Indianapolis community would put him at odds with the city’s Chinese population. In May, the small community would be rocked by the gruesome murder of Doc Lung, a local Chinese laundryman. The police immediately arrested Chin Hee, an immigrant who had just moved from Chicago and was employed by Doc Lung. This caused a major rift within the Chinese community, and they fragmented into two groups: Those who protested Chin Hee’s innocence and those who believed Chin Hee committed the murder. Moy Kee found himself in the crossfire of this rift when he began translating for the police and later grand jury and courts in the murder case. Many in the community felt that Moy Kee was betraying them by working as the government’s translator, the same institution that denied them citizenship and deported their people on a regular basis. The situation escalated to the point that Moy started receiving death threats attempting to coerce him into ending his translations for the government.

Despite the threats to his life, Moy Kee persisted, and the Grand Jury ultimately convicted three perpetrators, none of them Chinese, for the crime. The role he played in the court trial benefitted his relationships with the local government and police. He also received more media attention than he ever had before, further elevating his position in Indianapolis. However, this acceptance by local institutions came at the expense of Moy’s relationships with his fellow Chinese. Already separated from them due to his affluence and privileged status as an American citizen, working with the police led to some in community questioning whether Moy was loyal to the Chinese or the Americans. Rumors swirled and some whispered that E. Lung, the leader of the faction that defended Chin Hee, might be a better fit as the Chinese people’s representative. Subsequently, Moy would become increasingly paranoid about being ousted by the Chinese community as their unnamed leader. Later in life, when he was stripped of his high Chinese rank, he would immediately accuse fellow Chinese of engineering his social downfall.

Conclusion

By 1904, Moy Kee was undoubtedly the most prominent Chinese figure in Indianapolis and, despite a factionalized Chinese community, he was still recognized as the de facto leader. Better yet, Moy Kee had a home in Indianapolis that accepted him as both an American citizen and Hoosier. For a Chinese man to achieve this position was an incredible feat. Moy had hopscotched across the country, testified in multiple courts, accumulated a massive amount of wealth, and overcame duplicitous stereotypes to earn his citizenship and social standing. In many ways, it felt like Moy and his wife had achieved everything an immigrant to the United States could dream of.

However, no one could have predicted the actions of the Qing dynasty in the early 1900’s. A royal family infamous for their strict isolationism and rejection of Western diplomacy, they shocked the world by announcing that they would be participating in the 1904 St. Louis World Fair. Not only that, but they were appointing Prince Pu Lun, nephew of the emperor, as head of the Chinese fair commission. Critically for Moy, the Prince announced he would spend months before and after the fair touring America, including a ten-day visit to Indianapolis.

In the next installment, follow Prince Pu Lun’s royal visit to Indianapolis where he caused much fanfare. Additionally, we explore Moy Kee’s role in Pu Lun’s visit as he vies for an audience with the prince and eventually precipitates his “coronation” as the official Mayor of Indianapolis’ Chinese.

For further reading, see:

“Chinese,” The Polis Center, accessed May 2022, courtesy of IUPUI.edu.

Paul Mullins, “The Landscapes of Chinese Immigration in the Circle City,” October 16, 2016, accessed Invisible Indianapolis.

Scott D. Seligman, “The Hoosier of Mandarin,” Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History 23, no. 4 (Fall 2011): 48-55, accessed Digital Images Collection, Indiana Historical Society.

“Wants a Federal Place: Moy Jin Kee Raises a Disturbing Question,” Indianapolis News, March 8, 1901, 7, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.