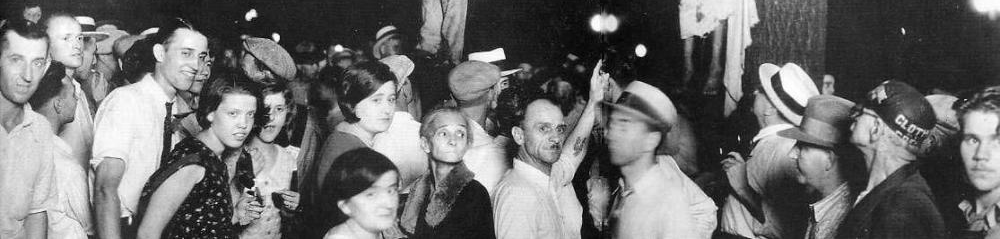

As they awaited the fate of Minor Moon, a legion of anxious men spilled down the stairs of the municipal courtroom, prodded by a “double chain” of Indianapolis patrolmen. Judge Paul C. Wetter had decided: Moon, a Black resident, would pay $50 for trespassing—an almost unfathomable fine for November 25, 1930, especially for a man recently evicted from his home at 409 West North Street. With this sentencing, Theodore Luesse—a white strike-leader in his mid-20s—cried from the front of the court room, “Comrades are we going to stand for this miscarriage of justice?”[1]

His comrades, still lining the stairs, responded, “We want justice!” They rushed back into the courtroom, where they exchanged blows with police officers. The Lafayette Journal and Courier reported, “The raging fighters smashed through the doorways into the corridors. Clubs rose and fell and fists were swung. Everyone was yelling.”[2] Luesse’s comrades, unemployed men attracted by the promise of Communism, eventually fled, leaving Luesse and organizer R.M. Spillman among the “avalanche of blue coats.” Police swiftly escorted Luesse and Spillman to jail, where, from their cells, they cried “injustice!” and “downtrodden proletariat!”

This would be one of dozens of arrests of Luesse for his role in agitating for better living and working conditions during the Great Depression. His actions would eventually culminate in a sentence at the notorious State Penal Farm in Putnamville, known as the “Black Hole of Indiana.” From this bleak environment, Luesse ran for governor on the Communist ticket. While the gubernatorial campaign inevitably failed, calls for Luesse’s release from imprisonment, for what many decried as simply exercising his “freedom of speech,” endeared widespread public support, including from Indianapolis businessmen like Franklin Vonnegut and clergy like Dr. Frank S. C. Wicks, as well as non-partisan groups like the ACLU.[3] His sentence also, to the dismay of judicial and government officials, increased Hoosiers’ interest in Communist ideals and ignited a series of social protests.

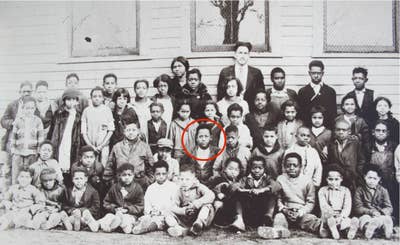

Much of Luesse’s inimitable life can be pieced together by pairing his 1995 recollections How I Got Out of Jail and Ran for Governor of Indiana: The Jim Moore Story* with U.S. Census records and newspaper articles, which typically corroborate his memories. The future firebrand, born in 1905 in Batesville to German immigrants, experienced hardship nearly from birth. When his mother died shortly after his first birthday, his father, likely grief-stricken and needing to provide for the family, moved to Indianapolis, where he varnished furniture in a factory. Theodore’s sisters were sent to an orphanage, and Theodore moved in with his aunt on a Batesville farm.[4] The family reunited a few years later, when his father brought his children to the capital city. There, Theodore recalled his father returning from work “full of sweat,” having undertaken grueling labor for pennies. Young Theodore tried to supplement this income with various jobs, like delivering newspapers and selling errant pieces of iron and rags.

This struggle likely informed Luesse’s later work as an organizer, as did attending local political meetings with his father. His experiences certainly cultivated in him a deep empathy for the disenfranchised, which manifested in middle school, when he protested the landing of U.S. Marines in Honduras.[5] Having exploited Honduran plantations for years, the U.S. sought to protect its profits after Hondurans denied access to them. Luesse was taught that the Marines were sent under the guise of protecting locals from “gangsters and guerrillas.” However, he challenged this narrative, telling teachers at his Catholic school that Hondurans were “fathers and mothers just like our fathers and mothers.” He recalled the nuns ridiculing his protestations. This incident, combined with their corporeal punishment, caused him to drop out of school.

In his early-teen years, Luesse found work as a messenger. He hauled boxes from “five and tens” and department stores, recalling, “Oh it was a big wagon with big horses and I was so proud of being able to drive that thing right in the heart of Indianapolis just going down the streets and hearing the automobiles and trucks and everything.”[6] According to Luesse, he then got a job at Western Union, where he led his first strike, demanding “equal work for equal pay, although we didn’t call it that.” He led fellow employees under the age of 16 to demand wages equal to that of older teenagers. Here, he demonstrated his signature mixture of intimidation and organizational prowess, threatening and sometimes employing physical harm against anyone who refused to strike. The tactic proved successful in raising wages.

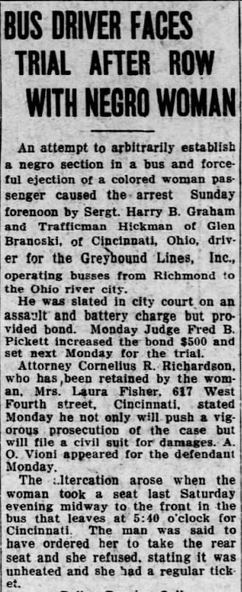

He then leveraged his job as a newsboy to work for social justice in the 1920s. He and some coworkers obtained an anti-Ku Klux Klan paper published in Chicago called The Intolerance.[7] They distributed copies at Jewish synagogues, Catholic churches, and churches in Black neighborhoods in Indianapolis, hoping to combat the rhetoric and ideals espoused in the Klan’s Fiery Cross paper. According to Luesse, publicizing information about the hate group helped pressure public officials into stemming the Klan’s influence in government.

Around 1930, Luesse joined the Communist Party, learning about local cases of unemployment and evictions through the party’s paper. Giving up a house-painting job, Luesse focused solely on combatting the deprivations wrought by the early months of the Great Depression.[8] He organized “flying squadrons,” groups of men who traveled to welfare and unemployment offices to ensure that the agencies were meeting people’s needs. He and his comrades also distributed copies of the communist paper and delivered speeches at Indianapolis factories. On Mondays and Tuesdays, Luesse visited the Kingan meat packing plant, informing workers about evictions around the city, arguing that, “If they can throw her out, they’ll throw us out tomorrow.” Such speeches attracted a crowd of onlookers, some of whom joined organizers in a parade to houses from which residents were being evicted. They hauled furniture back into renters’ homes, relying on a “security squad” comprised of military veterans, to intimidate police if they tried to intervene.

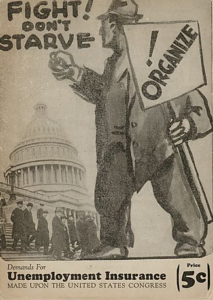

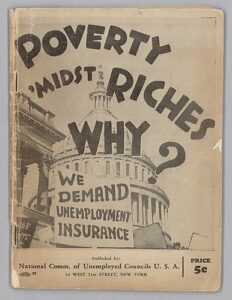

Luesse helped organize the Communist-based Unemployment Council of Indianapolis because the jobless had received “very little help from these organizations like the Socialist Party, the Workman’s Circle, and the Death Benefit Society. They were evolutionary and we were revolutionary. The Socialist Party believed that you could get everything on a ballot.”[9] The Unemployment Council, however, embraced public demonstrations and confrontations with public officials. Luesse contended that these were necessary in early 1931, as the socioeconomic privilege of lawyers, judges, and lawmakers shielded them from the realities of daily life for the unemployed. He noted, “They didn’t know about people having to pull things out of swill cans to eat, how people had to steal food to eat or things to live, how they had to burn up furniture in order to keep warm.”[10]

According to Bradford Sample’s 2001 Indiana Magazine of History article, Hoosiers received minimal help from local and state government, relying instead on aid from civic and charitable organizations during the early years of the Depression. Espousing traditional Hoosier principles of small government and self-sufficiency, Governor Harry G. Leslie and Indianapolis Mayor Reginald Sullivan refused to authorize relief bonds.[11] In fact, the Republican governor balked at requests to call a special legislative session in March 1932, fearing an unemployment relief bill would be introduced and that it would “‘be hard for any legislator not to vote for it.'”[12] Gov. Leslie opined that “such a procedure would demoralize the relief work now being done in committees. People now giving to unemployment relief would assume that their help was not needed if the state began making donations.'” He also refused to accept federal relief funds, viewing them as “direct threats to the tradition of local autonomy for relief in Indiana,” according to preeminent Indiana historian James H. Madison.[13]

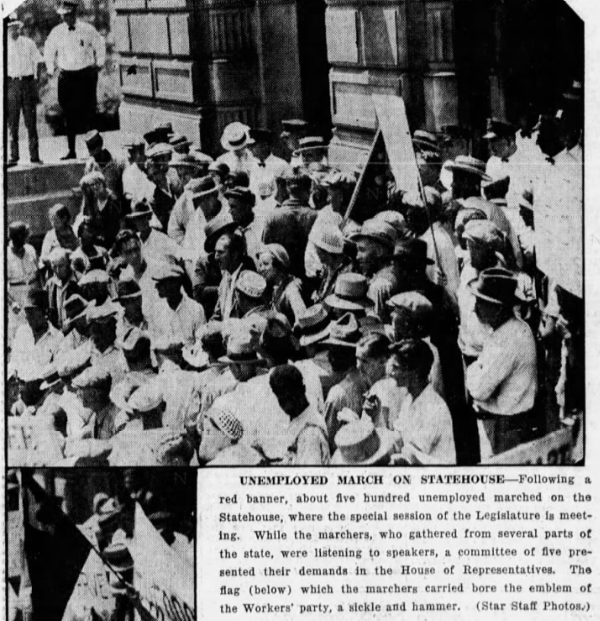

As inaction pitched Hoosiers further into destitution, their public protestations intensified. On January 6, 1931, the Indianapolis Times reported that Luesse and Council members led hundreds of unemployed men, about 60% of whom were Black, to the statehouse.[14] They failed in their attempt to meet Governor Leslie, whom they’d hoped would reconsider his stance on relief and housing. After this, Luesse led the men, desperately in need of warmth, to Tomlinson Hall. The group hoped that they could possibly find work there, as Tomlinson housed the Office of the Unemployed. Leading the delegation with Luesse was J.C. Moon (possibly a relative of Minor), dressed “fantastically in a dark blue uniform resembling that of hotel bellboys, and his head was topped by a scarlet fez hat with a flowing tassel.”[15]

As the marchers approached the building, they sustained momentum by chanting “When we see a cop we use him for a mop.”[16] They immediately encountered a police squadron at Tomlinson Hall, which culminated in a clash like that in the municipal courtroom. Banners bearing slogans like “Deliver Us From Starvation” and “To Hell With Your Lousy Charities” soon littered Delaware and Market Streets as some marchers fled and others attempted to occupy Tomlinson.[17] According to Luesse, police officers threw him on top of the gatherers and “motioned for the streetcars and automobiles to cut through the crowd.” After sustaining a blow to the nose, police again hauled him to jail. “My twenty-eighth ride!” he proclaimed.

Such conflicts demonstrated the painful dichotomy between the urgency of citizens’ needs and the inadequacy or unwillingness of governmental and societal structures to meet them. The fraught circumstances are likely why some lawyers continued to aid Luesse and why Judge Paul Wetter was fairly lenient in his punishment of him. In a serendipitous twist, Luesse had dated Wetter’s sister, establishing a friendly rapport with the future judge.[18] During their many courtroom encounters, Luesse and Judge Wetter exchanged perspectives, both seemingly perplexed by the other’s stance. Judge Wetter wanted to know why Luesse engaged in such provocation, and Luesse asked why Judge Wetter sentenced Hoosiers the way he did. Luesse recalled telling the judge:

‘There was this here old man that stole a pig and you put him one hundred and thirty days on the rock pile [penal farm]. You didn’t ask him why he stole the pig. You didn’t ask him about anything, but because of the fact that the law says that he should go to jail for one hundred and thirty days for stealing a pig you sent him. . . Now he’s got four breadsnappers at home. . . . he stole that pig in order to feed those children.’ (p. 47)

Luesse added, “You live in a world of hypocrisy. You go to church. . . . I’m up to here with all your bullsh*t, all your people’s bullsh*t, the priest’s and bishop’s and pope’s and everybody else.'” Apparently he earned Judge Wetter’s begrudging respect because, according to Luesse, Wetter ordered the turnkey to release him.[19] Just one month later, Luesse came again before Judge Wetter for having made “inflammatory speeches to a crowd assembled at a soup kitchen.”[20] Rather than fining or sentencing Luesse, Judge Wetter ordered him to report to City Hall for work digging ditches the following day.

Luesse employed another tactic to draw attention to the plight of Hoosier families. In How I Got Out of Jail, he described a “Mrs. Allen,” whose husband was unable to work due to tuberculosis. Having four children to care for, Mrs. Allen walked two to three miles to the welfare office for “gold soup,” so called because of the carrots that floated to the top of the broth.[21] She supplemented this paltry meal with rotten vegetables gathered from around the city. Luesse noted:

She was a fighter in every capacity and I loved that. So she was being evicted from her place and I convinced her that we were gonna get her a house. . . . We’re gonna have a big demonstration on the state house lawn and we’re going to have a house built there.

After Mrs. Allen agreed to this plan, Luesse and his comrades transported a dilapidated house to the statehouse grounds and distributed leaflets encouraging people to come “see how the unemployed has to live.” Two sides of the shanty were without walls, so for four days people observed Mrs. Allen care for her children and complete routine tasks with meager resources. Based on the publicity generated by the demonstration, Luesse was able to secure permanent housing for the Allen family.[22]

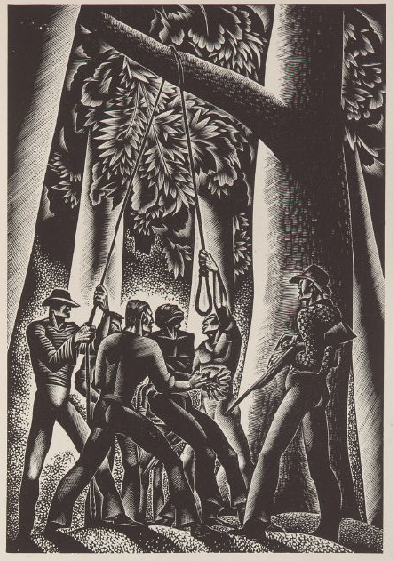

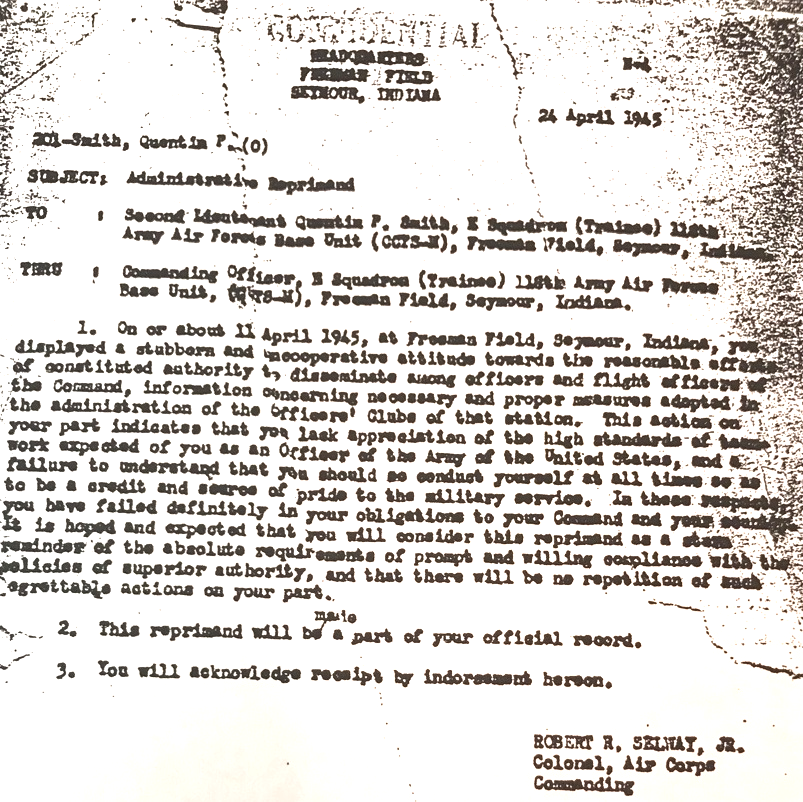

Throughout the spring, Luesse returned to jail several times for halting evictions and leading public demonstrations. His luck ran out after his thirty-fourth arrest, for which he interfered with the “eviction of a destitute Negro family,” and finally faced legal consequences. [23] Judge Frank P. Baker sentenced Luesse to one year at a penal farm in Putnamville, stating “‘no man has the right to take the law into his own hands. Any such man is a menace to society. I believe this man has tried to stir up resistance against the law and create disrespect for it, which in turn might lead to dangerous riots.'”[24]

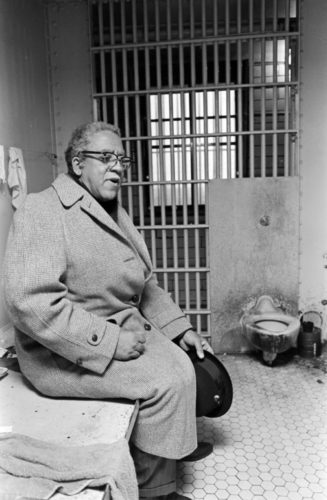

“Oh, Goddman, that was a hell of a place,” Luesse recalled about the jail.[25] In a sweltering quarry, he worked alongside men incarcerated for a spectrum of transgressions, including drunkenness, theft, and “social crimes”—meaning imprisonment for the crime of simply being a person of color. One man reportedly died because of the brutal work environment, a tragedy Luesse tried to expose by tying a letter to a kite.[26] For this attempt, he was placed in “the hole” for twenty days, where guards handcuffed and hung him out on a door for hours. Such allegations were confirmed by former prisoners, who presented Governor Leslie with affidavits testifying to such treatment.[27] Glenn Emmett Mulford wrote that after Luesse was released from solitary confinement, he “‘looked sick, worn-out and was bleeding from the nose.'” According to the Garrett Clipper, Governor Leslie dismissed the claims, declaring that Luesse was treated with “‘exceptional kindness.'”

The support Luesse engendered via his activism endured throughout his incarceration, as downtrodden Hoosiers continually demanded his release. In fact, the Evansville Press noted that his “case caused nationwide protests.”[28] At the end of November 1931, hunger marchers en route to Washington, D.C. stopped at the Putnamville prison farm, demanding to see Luesse.[29] Rebuffed, the automobile detachment continued on to Indianapolis, where they attempted to confront Governor Leslie about Luesse’s release and about authorizing war funds for the unemployed. By the spring of 1932, prominent Indianapolis clergymen and business leaders signed a petition for the Hoosier Communist’s release.[30] Indianapolis citizen Samuel Nathanson appealed to the governor after Luesse—who happened to be born with the unique “No. 1 count”—donated pints of blood to his sick daughter in an attempt to save her life.[31] Although Nathanson “was not in sympathy with Luesse’s political and economic beliefs,” he felt that Luesse’s punishment did not fit the crime, and that his generosity demonstrated his fitness as a citizen. He went so far as to offer Luesse a job at The Store Without a Name, for which he was manager.

After these efforts failed, local women led the charge to free Luesse. In April, they organized a protest of about one hundred supporters at the statehouse and defied police orders to relocate to Military Park. The Lake County Times reported that police had to forcefully remove a number of women “after they had climbed to the top of ornamental urns and had harangued their male companions to remain.”[32] Among the three arrested and charged with “inciting to riot and resisting arrest,” was a “Mrs. Fay Allen.” Described by the Indianapolis Star as a “mother of four children,” she was likely the same woman aided by the home demonstration organized on the statehouse grounds.[33] She appeared to take up the mantle for Luesse while he was behind bars, as she was arrested again the following month for “inciting a riot and interfering with legal process” during an eviction.[34] In July, a similar protest materialized at the statehouse, this time organized by unemployed men from The Region, who sought relief measures and the release of Luesse.[35] Hammond spokesman Wenzel Stocker told legislators that “‘mass starvation and suicide'” would occur in Gary if relief funds were not issued.

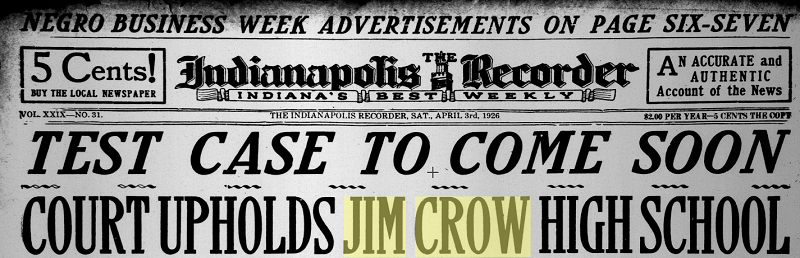

Given the apparent futility of such demonstrations, organizers hoped to effect change through electoral politics. In 1932, the Communist Party nominated Fay Allen for Secretary of State, Stocker for Lieutenant Governor, and Theodore Luesse, still serving time at the penal farm, for governor.[36] Luesse reported that some guards were sympathetic to his ideology and even supported his gubernatorial run. The candidates earned the public’s sympathy and respect, but not their electoral support, as born out by the 1932 returns. All three Communist candidates came in sixth out of seventh place, earning just over ninety votes each.[37]

Despite the loss, Luesse and his comrades increased interest among Hoosiers in the Communist Party, which as editorialist Paul B. Sallee noted in 1935, “could not develop a membership sufficient to muster a corporal’s guard.”[38] However, Luesse’s imprisonment—a veritable “miscarriage of law”—and the suppression of free speech wrought by his incarceration helped the Party grow by “leaps and bounds.” Sallee alleged that if the two major parties denied Hoosiers their “political rights and civil liberties . . . it is clear to any intelligent person that the people will throw off such restraint by any method.” While Hoosier voters did not forsake the two major parties, they did signal the desire for change by electing the state’s first Democratic governor in twenty years, Paul V. McNutt. Indiana’s new head of state had apparently been sympathetic to Luesse’s plight and in March of 1933 released him from Putnamville.[39]

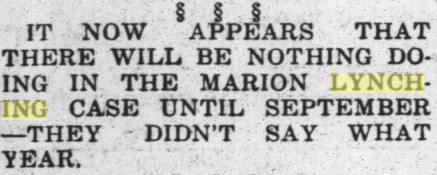

“Assured that Luesse would leave the state” upon his release, Gov. McNutt likely breathed a sigh of relief. Although progressive in his politics, McNutt surely preferred not having to contend with Luesse’s agitation.[40] But Luesse, dogmatic as ever, returned to Indianapolis the day after he left the penal farm. He stood on the courthouse steps before an audience of 200 women and men, most of whom the paper noted were African Americans, and “urged concentrated action of his followers against governmental officials to force them to favor demands of workers and the unemployed.”[41] Upon request, he made similar speeches in cities like Evansville, Munster, and Hammond in the following months.[42] According to Luesse, after his incarceration he worked with Indiana volunteers to organize a C.I.O. branch, made possible by passage of the National Industrial Recovery Act.[43] In August of 1933, while preparing to speak to a crowd of unemployed residents in Marion, he was arrested and transported to the Grant County jail, where a mob forcibly removed and lynched two young Black men in 1930.[44]

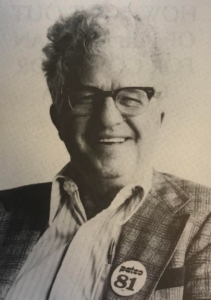

It appears that Governor McNutt could breathe a bit easier by 1935, as Luesse had transferred his organizational talent to other midwestern cities, like Belleville, Illinois.[45] Some time after leaving Indiana, Luesse assumed the alias “Jim Moore” and worked as a machinist. Shedding his association with the Hoosier state, he resided in St. Louis for a time, channeling his revolutionary spirit into protesting the Vietnam War.[46] After decades of activism, Moore joined his son, Stan, in San Francisco around 1967. They circulated 50,000 leaflets throughout the Bay Area, “telling the workers to organize stoppage of work for five minutes, ten minutes or any amount as a memorial to the people that died” in the war. After permanently relocating to the West Coast, Moore fought for equal representation in law enforcement and county government.[47] In the late 1980s, he served as a U.S. delegate to the World Peace Convention in Denmark, relying on young peers to help him travel to Copenhagen, as a lifetime of activism had worn down his body.[48]

Moore appeared to have tempered his radical impulses later in life, telling interviewer Claire Burch in 1995, “We’ve got enough anarchy! We don’t need no more anarchy. We need organization. We need discipline. We need to be moved to do things in order to be able to get legislation passed.”[49] Despite a philosophical shift, the nonagenarian continued to work for societal change. An average weekend for Moore meant rising at 7 o’clock, getting in some light exercise (mindful of his pacemaker), and walking over to the local hospital cafeteria for breakfast before folding copies of The People’s World. He then distributed them at the University of California, Berkley and in boxes throughout the city. Some Saturdays he breakfasted with college students to “talk over what is necessary for them to do” and on Sundays attended Humanist meetings or American-Soviet Friendship Society gatherings.[50] He ran a petition drive to convince the Montgomery Ward Company to donate one of its buildings to the City of Oakland, so it could be repurposed as a trade skill training center or housing for those experiencing homelessness.[51] Moore distributed leaflets at local welfare and unemployment offices and attended Bay Area demonstrations almost until his death.[52]

With characteristic resolve, Moore achieved his goal to reach the age of 100, passing away in 2005 just two weeks after the milestone birthday. Despite playing a large role in Indiana’s labor tradition and making an indelible impact on his native state during the Depression, he has largely been forgotten. Crusaders such as himself helped centralize Indiana government and cultivate a new generation of organizers, who demanded more from their government during those tumultuous years.

While some Hoosier leaders disapproved of Luesse’s resistance, it helped catalyze necessary change during unprecedented circumstances. After all, the New Deal was not a foregone conclusion and many state lawmakers were slow to recognize the scope of constituents’ needs. Luesse’s many public protests and his vociferous criticism of Governor Leslie’s inaction infused some Hoosiers with the spirit of reform. Primed for change, voters decided not to elect Gov. Leslie to a second term, instead electing progressive candidate Paul V. McNutt in 1933. According to historian Linda C. Gugin, Gov. McNutt’s “liberal social-welfare programs . . . marked a significant shift in the direction of assistance to those in need” and created a “more centralized, modernized, and professional welfare system.”[53]

Luesse’s unflinching demand for accountability and relief measures may resonate with modern Americans, as they grapple with the current spike in inflation, swelling gas prices, the mounting student loan debt crisis, and pandemic-related housing displacement. Certainly, those who support a social safety net relate to Theodore Luesse’s belief that:

Everybody has the right to live just because they are alive, and in order to live, a person has to have food, clothing and shelter, health and education. When he doesn’t receive that by his own ingenuity it is necessary for the government to help him. That is why we have governments—to help those people who cannot help themselves, not just to make rules and regulations.[54]

* According to this publication, he eventually went by the alias “Jim Moore,” but it is unclear when or why he did so. It appears he employed this moniker after leaving Indiana, so he will be referred to as “Theodore Luesse” during the time he lived there.

Notes:

[1] “Indianapolis Police Battle Riotous Crowd of Radicals,” (Lafayette) Journal and Courier, November 25, 1930, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[2] Ibid.

[3] “Governor Believes Luesse Not Ready to Obey State Laws,” (Richmond) Palladium-Item, April 7, 1932, 7, accessed Newspapers.com; “Liberties Union to Champion Prisoner,” Evansville Press, June 23, 1932, 5, accessed Newspapers.com.

[4] “Theodore Luesse,” 1910 United States Federal Census, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; How I Got Out of Jail and Ran for Governor of Indiana: The Jim Moore Story (Oakland, CA: Regent Press, 1995), p. 5-6.

[5] How I Got Out of Jail, p. 5-6; Obituary, “Jim Moore, Press Builder, Dies at 100,” People’s World, January 7, 2005, accessed Peoplesworld.org.

[6] “Theodore Luesse,” Indianapolis, Indiana City Directory, 1920, U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; “Hayes Body Strike Ends in Wage Pact,” Indianapolis Times, April 18, 1930, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; How I Got Out of Jail, p. 10-11, 13, 26-34.

[7] How I Got Out of Jail, p. 106-107.

[8] How I Got Out of Jail, p. 32-34.

[9] “To Protest Eviction of Tenants,” Indianapolis News, January 5, 1931, 23, accessed Newspapers.com; Quote from How I Got Out of Jail, p. 109.

[10] How I Got Out of Jail, p. 52.

[11] Bradford Sample, “A Truly Midwestern City: Indianapolis on the Eve of the Great Depression,” Indiana Magazine of History 97, iss. 2 (June 2001), accessed IUScholarWorks Journal.

[12] United Press, “Leslie Again Blocks Session: Refuses Plea that He Call Legislature,” Evansville Press, March 26, 1932, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[13] James H. Madison, Indiana Through Tradition and Change: A History of the Hoosier State and Its People, 1920-1945 (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society, 1982), p. 109.

[14] Quote from “City Police Use Clubs to Halt Rioters,” Indianapolis Times, January 6, 1931, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Communist Agitators Arrested,” Late County Times, January 6, 1931, 17, accessed Newspapers.com.

[15] “City Police Use Clubs to Halt Rioters,” Indianapolis Times, 1.

[16] How I Got Out of Jail, p. 43-44.

[17] “City Police Use Clubs to Halt Rioters,” Indianapolis Times, 1.

[18] How I Got Out of Jail, p. 45.

[19] Ibid., p. 47.

[20] “Court Provides Jobs for Orators,” (Lafayette, IN) Journal and Courier, February 6, 1931, 13, accessed Newspapers.com.

[21] How I Got Out of Jail, p. 41-42, 156.

[22] Ibid., p. 41-42.

[23] “Alleged Red Held Again,” Indianapolis News, April 24, 1931, 37, accessed Newspapers.com; “Hunger Marchers are Home Bound,” Late County Times, May 5, 1931, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; “Trio Arrested at Capital Released,” (Richmond, IN) Palladium-Item, May 5, 1931, 8, accessed Newspapers.com; Quote from “Liberties Union to Champion Prisoner,” Evansville Press, June 23, 1932, 5, accessed Newspapers.com.

[24] “Radical Chief Gets Sentence on State Farm,” Kokomo Tribune, May 23, 1931, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[25] How I Got Out of Jail, p. 48.

[26] Ibid., p. 50-51.

[27] “Leslie Denies ‘Red’ Has Been Abused at Penal Farm,” Garrett Clipper, May 26, 1932, 5, accessed Newspapers.com.

[28] “Theodore Luesse Will Speak Here,” Evansville Press, March 12, 1933, 5, accessed Newspapers.com.

[29] “Marchers Denied Visit with Luesse at State Penal Farm by Warden,” Kokomo Tribune, November 30, 1931, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[30] “Governor Believes Luesse Not Ready to Obey State Laws,” (Richmond, IN) Palladium-Item, April 7, 1932, 7, accessed Newspapers.com; “Governor Refuses to Release Luesse,” Palladium-Item, October 4, 1932, 3, accessed Newspapers.com; How I Got Out of Jail, p. 57.

[31] “Luesse Gave Blood for Little Girl; Father Asks Release, Promises Job,” Indianapolis Star, April 15, 1932, 10, accessed Newspapers.com.

[32] Quote from “Mob of Reds are Led by Women,” Late County Times, April 25, 1932, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[33] “2 Women, 1 Man Held as Rioters,” Indianapolis Star, April 26, 1932, 11, accessed Newspapers.com.

[34] “Two Held at Eviction,” Indianapolis News, May 13, 1932, 25, accessed Newspapers.com.

[35] “Jobless Army Asks Indiana Legislature for Relief Funds,” Chicago Tribune, July 20, 1932, 2, accessed Newspapers.com.

[36] “May Day is Celebrated at Two Meetings Here,” Indianapolis Star, May 2, 1932, 11, accessed Newspapers.com; “Hammond Man is Named for State Office,” Late County Times, September 21, 1932, 3, accessed Newspapers.com; “Townsend for Senate,” Indianapolis Star, September 21, 1932, 12, accessed Newspapers.com; How I Got Out of Jail, p. 52.

[37] South Bend Tribune, November 10, 1932, 13, accessed Newspapers.com.

[38] Paul B. Sallee, “The Message Center: ‘Red Scare’ Law Held Communist Aid,” Indianapolis Times, March 15, 1935, 32, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[39] “Back from State Farm, Luesse Speaks to 200,” Indianapolis Star, March 5, 1933, 9, accessed Newspapers.com; “Theodore Luesse Held at Marion,” Indianapolis News, August 5, 1933, 17, accessed Newspapers.com; How I Got Out of Jail, p. 56-57.

[40] “Theodore Luesse Held at Marion,” Indianapolis News, August 5, 1933, 17, accessed Newspapers.com; How I Got Out of Jail, p. 56-57.

[41] “Back from State Farm, Luesse Speaks to 200,” Indianapolis Star, 9.

[42] “Theodore Luesse Will Speak Here,” Evansville Press, March 12, 1933, 5, accessed Newspapers.com; “Prepare for Luesse Meeting,” Late County Times, March 20, 1933, 10, accessed Newspapers.com.

[43] How I Got Out of Jail, p. 62.

[44] “Theodore Luesse Held at Marion,” Indianapolis News, August 5, 1933, 17, accessed Newspapers.com; “Theodore Luesse Freed from Grant County Jail,” Indianapolis Star, August 8, 1933, 18, accessed Newspapers.com.

[45] “Sewage Plant and Richland Creek Project Placed on List,” Belleville [Illinois] Daily News-Democrat, February 5, 1935, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; How I Got Out of Jail, p. 72, 85.

[46] How I Got Out of Jail, p. 85, 190.

[47] Ibid., p. 151, 182.

[48] Ibid., p. 129-130.

[49] Ibid., p. 184.

[50] Ibid., p. 185.

[51] Ibid., p. 180.

[52] “Jim Moore, Press Builder, Dies at 100,” People’s World, 2005.

[53] Linda C. Gugin, “Paul V. McNutt: January 9, 1933-January 11, 1937,” in eds., Linda C. Gugin and James E. St. Clair, The Governors of Indiana (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press, 2006), p. 296.

[54] How I Got Out of Jail, p. 146.