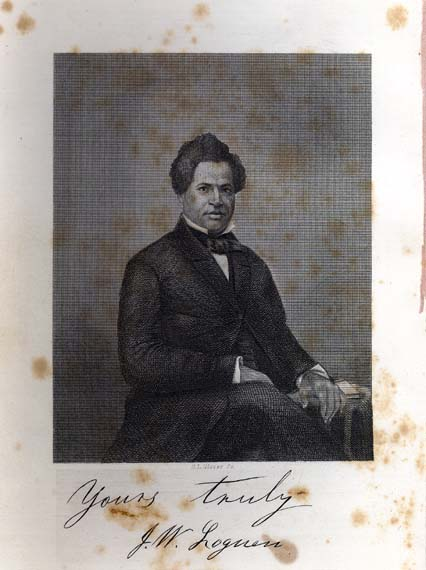

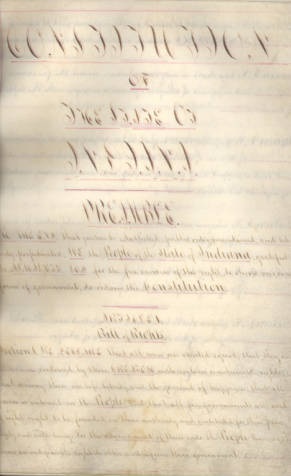

The release of the new Ben-Hur movie this summer reminded us of the story’s Hoosier origins. This latest production from Mark Burnett and Roma Downey is the fifth time that film producers have interpreted Crawfordsville native Lew Wallace’s best-selling novel for the screen. Many are familiar with the 11 Academy Award winning adaptation starring Charlton Heston in 1959 and most film buffs know that there were two earlier versions in 1907 and 1925. The 1907 film prompted a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision that protected copyrighted works from unauthorized motion picture adaptation. The 1925 film arguably has a better chariot race than the 1959 movie. There was also a forgettable and regrettable Canadian mini-series reboot of Ben-Hur in 2010.

In a world of constant movie reboots, one ponders: if Lew Wallace were alive today and re-wrote Ben-Hur in a contemporary setting, would he have Ben-Hur racing in the Indianapolis 500?

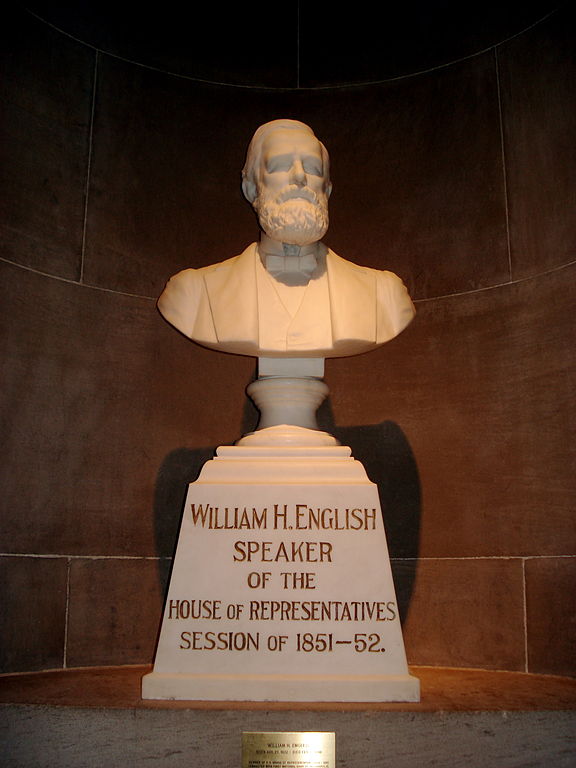

What if we told you that Ben-Hur did, in fact, race at Indianapolis? Of course, the race did not take place at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway; instead it took place in 1902 at English’s Theater during the Ben–Hur stage play’s first visit to Indianapolis.

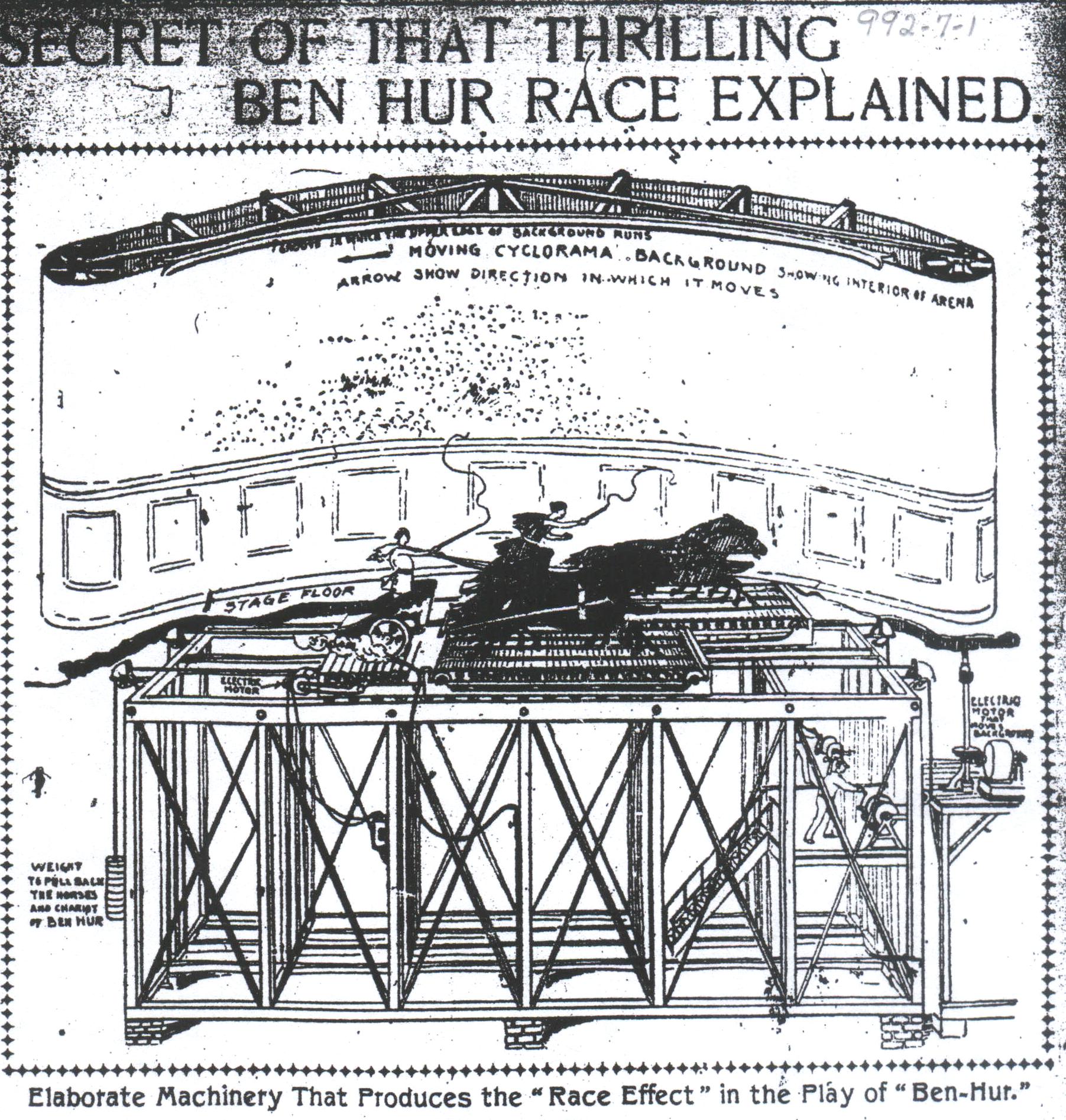

On November 13, 1902, the Indianapolis News reported “J.J. Brady is here in advance of ‘Ben-Hur,’” and “brings with him a corps of stage carpenters and mechanics, who have practically to reconstruct the stage . . . so that the play may be given properly.” Although English’s stage was new, crews needed to rebuild it in order to accommodate the chariot race. Producing that scene called for eight live horses running at full gallop on treadmills, cycloramic scenery and, other apparatus. All this equipment and animals imposed an estimated weight of over 50 tons on the stage, which required pouring a special cement foundation. The public was anxious to see the spectacle, even if it meant staking out a place in line many hours in advance. The Indianapolis News reporter observed:

“A few individuals sat and shivered all night in the lobby of English’s waiting in patience and with an unwonted supply of cash in their pockets for the box office to open. They were men who had been hired to buy seats for some of the performances of ‘Ben-Hur.’”

Ticket prices ranged from fifty cents to two dollars. Even at that rate, a day after the tickets went on sale, the English Theater reported “over $10,000 was taken in at the box office window” and representatives for the producers of the play (Marc Klaw and Abraham Erlanger) announced that the sales “beat all records for the play in advance sales.” The Supreme Tribe of Ben-Hur, a national benevolent society headquartered in Wallace’s hometown of Crawfordsville, nearly bought out one performance by itself. The Tribe planned to run an excursion via train for its members from Crawfordsville to see the play.

However, a few members of the Hoosier public were dubious about purchasing tickets. In particular, one woman was of the opinion that the play was to take two weeks to complete. When the box office manager informed her that the entire play was presented every night, she remained quite suspicious that anyone “could put all that book into a one-night drama.”

Production managers sought to cast extras from Indianapolis’s denizens, advertising a salary of $4.25/week. That was enough to encourage a crowd of men, women, and children to stand outside in a late Indiana autumn for an hour and a half waiting for their opportunity at show business. An assistant stage director eventually made an appearance and sorted through the crowd. One “gray beard” was turned away because the assistant director believed him not to be “nimble afoot.” The rejected man futilely protested to the assistant director and argued “he could get around faster than two-thirds of the younger fellows that had been accepted.”

With the extras cast, the production opened on Monday, November 25, 1902. After witnessing opening night, an Indianapolis reporter wrote, “There [will] be critics who see nothing good in the American stage or in the works of American dramatist: if the American stage had done absolutely nothing worthy in its long career but this, had its fame to rest solely on this production of ‘Ben-Hur’ it has justified its existence.”

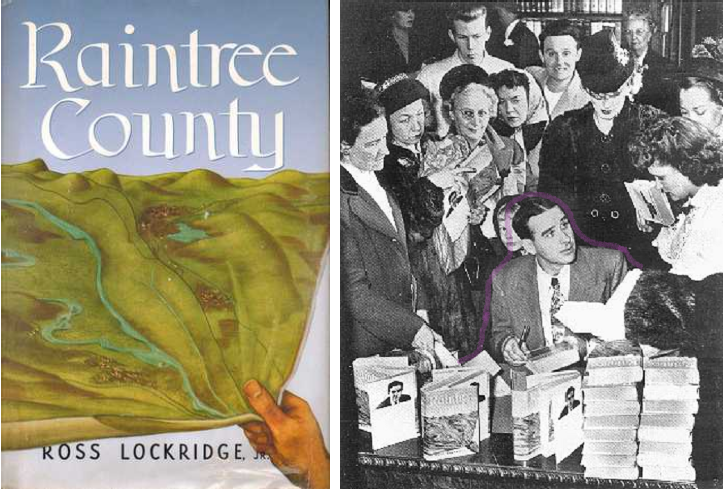

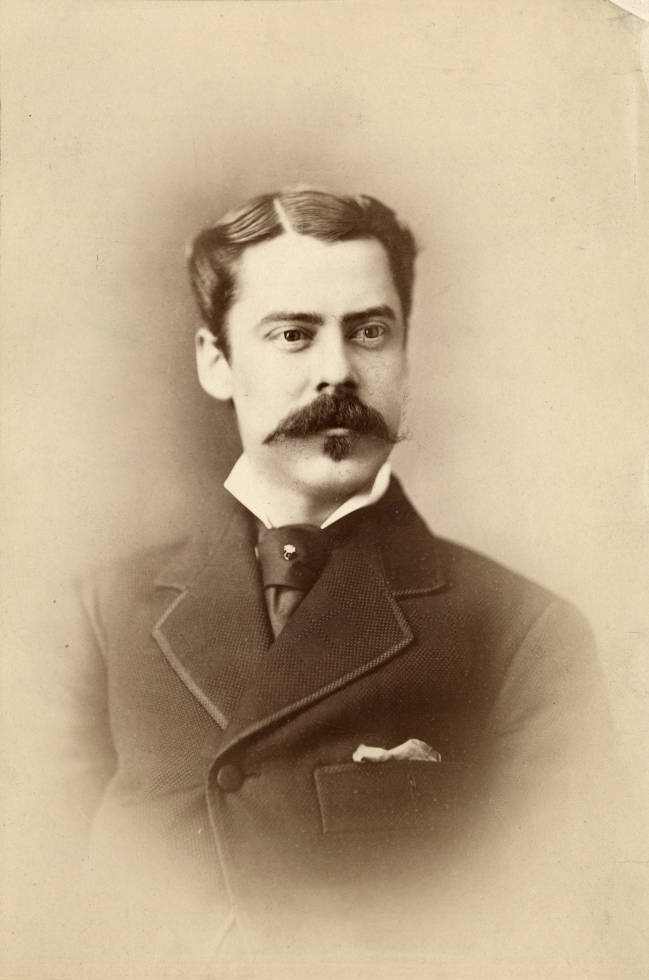

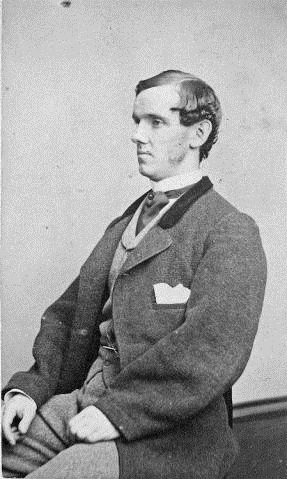

The cast, as it appeared in Indianapolis, included William Farnum as Ben-Hur and Basil Gill as Messala. Farnum’s performance was described as realizing the part to the fullest degree. Among the other actors and actresses in the production, Mabel Bert’s portrayal as the mother of Hur is worth noting because she was the only cast member with a major role to be with the company continuously since the production opened on November 29, 1899 in New York City. Mrs. Bert told a reporter,

“I have always been the mother of Ben-Hur – various Ben-Hurs, however, for Mr. Farnum is the third I have mothered on the stage…It does make me a trifle lonely sometimes to lose my stage children and stage friends that way. But then, too, it affords a certain amount of variety that is interesting and keeps my work from becoming at all monotonous.”

The public certainly found nothing monotonous about the play. In fact, the production was originally slated to run for two weeks in Indianapolis, but four days after opening night the Indianapolis News reported that the high demand for tickets had prompted producers to extend the play for another week. Box office receipts for the first two weeks alone were estimated in excess of $35,000. That figure broke all box office records for Indianapolis and was the highest figure for all productions of Ben-Hur to that date.

The Indianapolis News attempted to describe the sales phenomenon in Indianapolis:

“‘Ben-Hur’ occupies a unique position on the native stage, since it appeals alike to habitual theater patrons and those who seldom find enjoyment in offerings of the stage. While the elaborate scenic equipment and realistic chariot race command the admiration of the spectators, the rare beauty and force of ‘Ben-Hur’ as a drama give a lasting distinction to this most uplifting, inspiring and soul-stirring play.”

This description of the popularity of Ben-Hur, while no doubt true, neglects that a major reason for the large turnouts was because the author of Ben-Hur was a native Hoosier son. Some Indiana cities, such as Covington, Franklin, and Noblesville, brought large numbers of their population and sold out individual performances. In fact, Covington could not secure as many tickets as they had citizens who wanted to attend; the Indianapolis Sentinel reported that a small riot broke out as a result.

While various Indiana cities were hoping to witness the performance, Crawfordsville was no exception, as it was Ben-Hur’s birthplace. A contingent of Athenians and Montgomery county residents had the theater to themselves for a performance on December 2. Among those in attendance at that performance was James Buchanan Elmore, aka the Bard of Alamo. After witnessing the arrest of the Hur family, Buchanan leaned over to a newspaper reporter and said, “Seems to me if I was bossing that show I would make the actors speak softer and not so rough, it don’t seem like Scripture voices.”

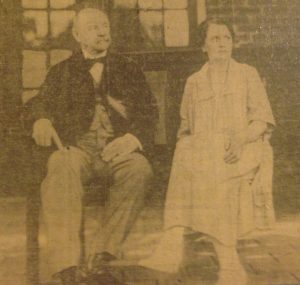

Although the December 2 performance hosted one Montgomery County literary celebrity, another one was conspicuously absent, that being General Lew Wallace, the author of Ben-Hur. Wallace was recovering from an illness during the Crawfordsville excursion. However, he was sufficiently recovered to attend a matinee with his son, daughter-in-law, and his two grandsons on December 12. Wallace watched most of the play from a private box and tried to remain as inconspicuous as possible, lest he be called upon to deliver a speech. Wallace and his party were invited behind the stage so that they could witness how some of the scenes were produced, especially the chariot race. Wallace took special interest in watching the race and all of the mechanization that was involved. While backstage, Wallace met the starring members of the cast and reportedly chatted for several minutes with the actor incarnating his literary creation. Before returning to his box Wallace remarked to a stage manager that the production had reached a state of perfection. Ben-Hur ended its stay in Indianapolis the day after Wallace’s visit, before moving to Milwaukee for a two-week engagement.

Eleven years later, when Ben-Hur was making another visit to Indianapolis, Hector Fuller aptly noted in the Indianapolis Sunday Star,

“If Indiana had contributed nothing else, save this one play to the American stage it might be counted that the Hoosier state had done its part. For ‘Ben-Hur’ is the dramatic marvel of the age. It has held the stage now for fourteen years, and in that time over 10,000,000 people have seen it.”

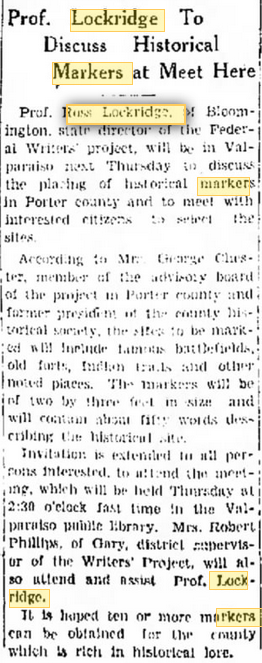

Learn more about Lew Wallace, his father David Wallace, his stepmother Zerelda Wallace, and his mother Esther Test Wallace with other IHB historical resources.

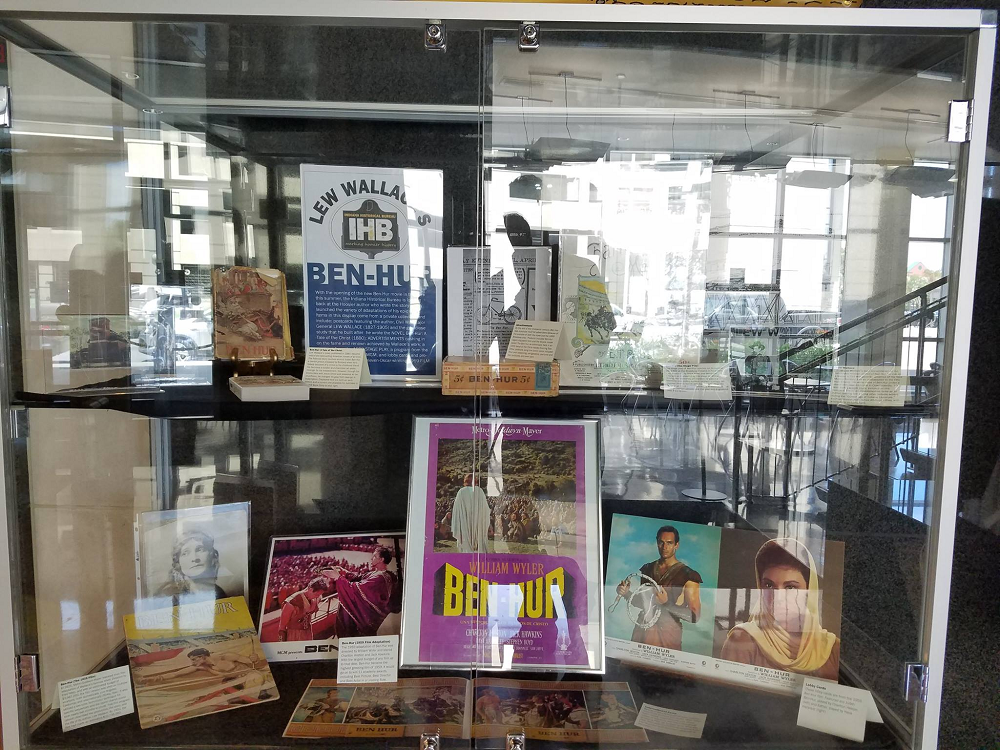

Stop by our exhibit in the Indiana State Library to see memorabilia from productions of Ben-Hur.

Learn about the history of public health in Indiana and Wiley’s contributions with our publication

Learn about the history of public health in Indiana and Wiley’s contributions with our publication