Indiana’s state flag waves from all corners of the state, from the Statehouse to a farmhouse in Selma. It has so proliferated the state’s landscape that it’s easy to assume it has flown since Indiana’s birth. However, it was not until 100 years after statehood that Indiana got a flag representative of the Hoosier people; and it was decades after that before the public recognized the design. We’ll examine why so much time elapsed before Hoosiers proudly hoisted blue and gold from their flagpoles.

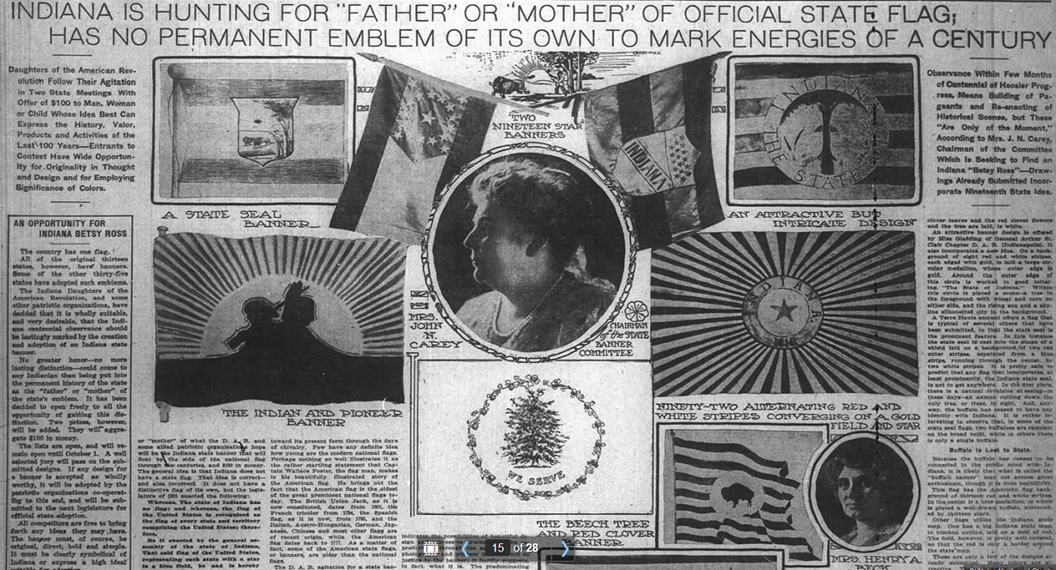

We were surprised to learn that the U.S. flag was made Indiana’s official state flag by the Indiana General Assembly in 1901. This changed when, in 1914, Indiana Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) delegates Mary Stewart Carey, of Indianapolis, and Mrs. William Gaar, of Richmond, attended the 23rd Continental Congress of the National Society, DAR in Washington, D.C. At the conference they observed that the Memorial Continental Hall was decorated with state flags, but that Indiana was one of few states missing representation. The women returned to Indiana with the goal of obtaining a state banner that was representative and unique to Indiana, particularly in light of Indiana’s upcoming centennial of statehood. The Indianapolis News reported on March 11, 1916 that:

The Indiana Daughters of the American Revolution, and some other patriotic organizations, have decided that it is wholly suitable, and very desirable that the Indiana centennial observance should be lastingly marked by the creation and adoption of an Indiana state banner.

The Indiana DAR established a State Flag Committee, headed by Carey, and hosted a public competition for the design of a state banner. The Indianapolis News reported in 1916 that the DAR chapter was careful not to infringe on the existing state flag, reporting that the group:

[I]s not proposing the creation or adoption of a state flag. There is no disposition to try to share the place of the one flag, but there is a feeling that it is wholly appropriate to adopt an individual standard or banner. Other states—all of them thoroughly patriotic and loyal—have done so.

The committee offered a $100 award for the winning entry and received over 200 submissions from Hoosier men and women, as well as applicants from other states. Carey contended in a report of the State Flag Committee:

It is difficult to find a motive to be expressed on our banner, as Indiana has no mountain peak, no great lake or river exclusively its own—but it is possible to find some symbol expressive of its high character and noble history.

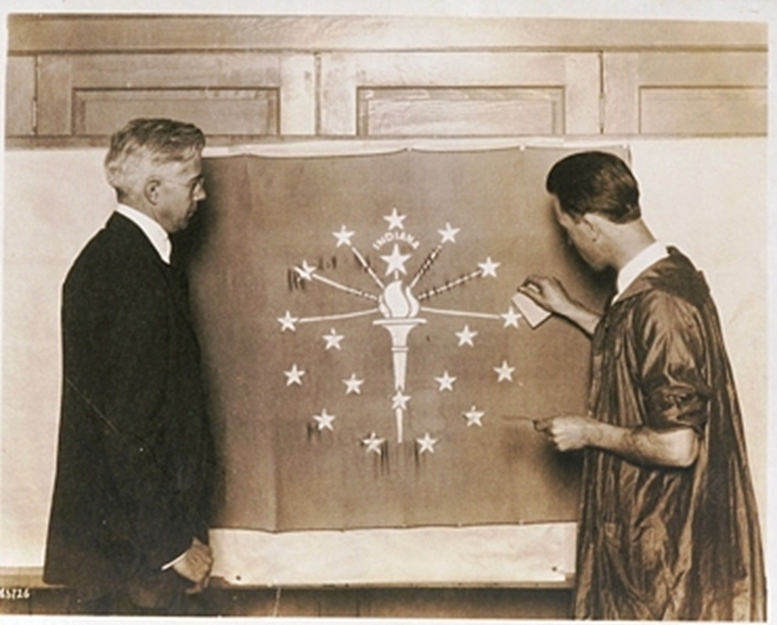

As the banner competition progressed, Carey urged contestants to submit simpler designs that could be “recognized at a distance, and simple enough to be printed on a small flag or stamped on a button.” She encouraged applicants to design banners “striking in symbolism” and utilize colors differing from those of the U.S. flag. Hadley’s submission met these suggestions, featuring a gold torch representing liberty atop a blue background. Radiating from the torch were thirteen stars on the outer circle to represent the thirteen original states, five stars in the inner circle to represent the states admitted before Indiana, and a larger star symbolizing the State of Indiana.

(In 1976, David Mannweiler of the Indianapolis News reported that Hadley’s additional submissions in 1916 won prizes for first, second, third and all honorable mention awards. Mannweiler noted that one of the entries included a tulip tree leaf and blossom and another featured an ear of corn with an Indian arrowhead).

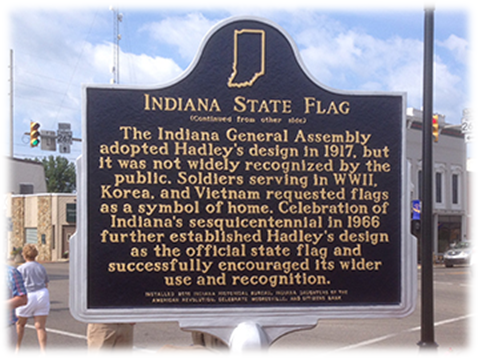

After Hadley’s design was selected, it was submitted to the Indiana General Assembly in 1917 for approval and adoption as Indiana’s official state banner. The legislature ordered that the word “Indiana” be added above the star representing the state. The enacted law stated that the banner “shall be regulation, in addition to the American flag, with all of the militia forces of the State of Indiana, and in all public functions in which the state may or shall officially appear.” So as not to conflict with the 1901 legislation, the U.S. flag remained Indiana’s official state flag and Hadley’s design was referred to as the Indiana state banner. In 1955, the General Assembly approved an act making Hadley’s design the state flag of Indiana.

***

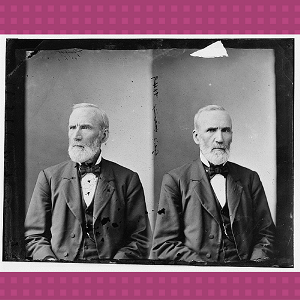

The flag’s designer was born August 5, 1880 in Indianapolis, but spent much of his life in Mooresville, Indiana. Hadley initially attended Indianapolis High School (later renamed Shortridge High School), but transferred to Manual Training High School to study under “Hoosier Group” artist Otto Stark. According to fine arts curator Rachel Berenson Perry, in the fall of 1900 Hadley enrolled in the Pennsylvania Museum and Industrial School of Arts in Philadelphia and studied interior decorating for two years, afterwards working as an interior decorator in Chicago.

Hadley returned to Mooresville and primarily painted watercolors of local landscapes, Some of the subjects he commonly depicted included cabins, streams, woods, outhouses, farmhouses and shrubbery. Perry reported that in 1921 Hadley’s studio in the Union Trust building in Indianapolis had become “well known among art enthusiasts.” The Indianapolis Star noted in December of that year that Hadley traveled through Italy, Switzerland, France, England and Belgium, painting water colors that he later exhibited at the Woman’s Department Club in Indianapolis. The Star article described the water colors:

Of charming quality and lovely color, a veritable delight as to design and pattern, likewise expressive of poetic feeling and an imaginative faculty that bespeaks the true artist, these pictures form an important series in the beautiful work coming from Mr. Hadley’s brush within the last few years that is indeed distinctive.

Hadley gained a reputation for his watercolors and frequently exhibited his work in Indianapolis. He participated in Indiana Artist Club exhibitions and belonged to the prestigious Portfolio Club. The Indianapolis Star Magazine and a Hoosier Salon booklet reported that Hadley received awards for his watercolors at the annual Hoosier Art Salon and Indiana State Fair. A 1922 Indianapolis Star article asserted that the winning Indiana State Fair pieces conveyed “freshness of outlook, evidence of fine color sense and a feeling for harmony and balance. His creative ability and versatility are evident in the handling of various subjects in different mediums.” That same year Hadley was invited to teach at the John Herron Art Institute, where Art Association of Indianapolis bulletins show he frequently exhibited watercolors.

Hadley joined the faculty of the John Herron Art Institute in the fall of 1922 as an interior decorating instructor. The Indianapolis Star reported in November of that year that he taught topics relating to “color design and arrangement of furniture in home interiors.”

In 1929, Hadley’s job at Herron transitioned to water-color instructor. According to The American Magazine of Art, a change in school administration in 1933 led to the dismissal of Hadley along with seven other professors, including “dean of Indiana painters” William Forsyth. Hadley transferred to the Art Institute’s museum in 1932, working as assistant curator.

An Indianapolis Star Magazine article, published in 1951, highlighted the prevalence of his work, stating that “there is a Hadley water color in most of the Indianapolis high schools, and a large one is in the John Herron Art Institute.” The article added that Hadley’s “products are in demand everywhere. Many established artists regard him as a great teacher, partially responsible for their own successes. He is regarded as one of the best water color technicians of the Middle West.” David Mannweiler noted similarly in his 1976 Indianapolis News article that Hadley is regarded as “dean of Hoosier watercolor painters.”

***

Hadley’s banner submission was met with some apathy, as the Attica Ledger noted in 1917 that:

there were several of the lawmakers that were not enthusiastic over the proposition for a state flag and Gov[ernor James P.] Goodrich himself thought so little of the proposition that he allowed it to become a law without his signature.

Similarly, the Hoosier public remained largely unaware of the emblem. The Ledger suggested that same year that most readers would not recognize the banner if they passed it. The Indianapolis News reported at the end of 1917 that the banner had yet to be publicly displayed (having only been exhibited at a DAR convention) until Carey presented it to the crew of the U.S.S. Indiana. Perry noted that after Carey’s gesture the banner “virtually disappeared from public consciousness for several years.” Indianapolis newspapers reported in 1920 that the public remained generally unaware of the banner’s existence. The Indianapolis News asserted that “probably not one person in a thousand knows what the state flag is.” An Indianapolis Star article lamented the banner’s lack of visibility, stating:

[I]n the four years that have elapsed since the centennial celebration, this flag has never been displayed at a public gathering with the exception of the celebration of the centennial of Indiana [U]niversity, and then, through the instrumentality of a pageant master from another state. It was not seen during the Indianapolis centennial celebration, nor during the recent encampment of the Grand Army of the Republic. . . The flag is not to be found in the Statehouse . . . some one in authority should see that this flag should be manufactured and should be displayed on all suitable occasions together with the flag of the United States.

The Indianapolis News reported in 1931 that members of the Mooresville Delta Iota Chapter of Tri Kappa made state banners to sell through their sorority. Member M.E. Carlisle stated “‘We have felt that the state banner has not been receiving the proper attention in the state’” and that “‘many people do not know that we have one and some that do would not recognize it if they saw it. Our idea is to acquaint the state with its banner.’”

Visibility of the banner increased somewhat when American soldiers serving overseas in World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War requested it as a symbol of home and solidarity. The Indianapolis Star reported in 1942 that:

When Hoosier soldiers gather in USO headquarters or other recreation spots, the Indiana flag of blue and gold is a symbol of home, displayed much more widely now than it was during World War No. 1. Viewing the banner prompts handclasps which are the beginning of friendships, stories of people at home, and singing of ‘On the Banks of the Wabash.’

The banner was sent to Hoosier soldier Private First Class Edman R. Camomile, serving in the Korean War, who flew it from a hilltop on the war front. He stated “‘It is the most wonderful thing that could happen to me. Just knowing the United States flag and all 48 state flags are flying high over different areas of Korea shows that they all stand for peace to all mankind.’” According to the News, an unofficial query showed that the state did not mass produce the flag and that they were made only when ordered, speaking to the continuing lack of demand for the emblem. Marine Corporal Tony Fisher, fighting in the Vietnam War, requested an Indiana flag. He flew it over his gun pit, returning it “tattered and torn and perhaps bullet nicked.”

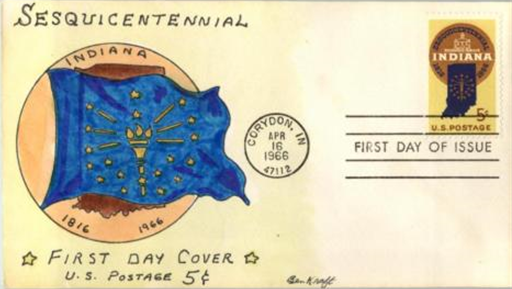

By 1966, many Hoosiers recognized Hadley’s design because of concerted efforts by the Indiana legislature to encourage celebration of the state’s sesquicentennial. On February 24, 1965, the Indiana House of Representatives approved a resolution stating observance of the sesquicentennial “should include widespread display of the State Flag of Indiana throughout the State.” The resolution directed state-funded institutions and schools to purchase and display the flag. Additionally, the Indiana Senate approved a resolution honoring Hadley for his design, stating “in connection with the observation of the Sesquicentennial Celebration in 1966, [the Senate] does hereby honor and commend Mr. Paul Hadley, an octogenarian citizen of the State of Indiana, for his brilliant and perceptive work in designing the official flag of the State of Indiana.”

The measures were largely successful in bringing awareness to the flag. A June 2, 1966 Indianapolis News article reported “almost any school child can recite the significance of the present official flag” and that “today it is known by all public-spirited Hoosiers of all ages.” The Delphi Journal noted that the state flag, purchased by the “Sesqui” group, was on display and would be exhibited at the REMC auditorium. The Tipton Tribune informed readers that the Sesquicentennial Queen would be delivering a tribute to Hadley. The anniversary of statehood was commemorated on a national scale at the Tournament of Roses Parade in Pasadena, California with a float depicting the state flag and other symbols of Indiana. The flag continues to be used publicly to represent and celebrate the Hoosier state, such as its display at the 2015 Statehood Day, an event that kicked off Indiana’s bicentennial celebration.

Check out IHB’s new historical marker and corresponding notes to learn more about the flag and its designer.

10.

10.