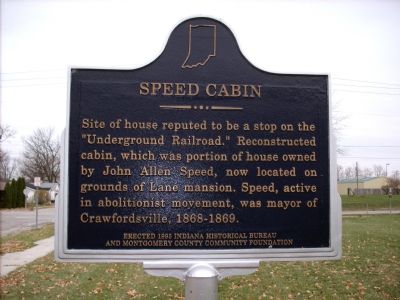

Researching the Underground Railroad (UGRR) is a difficult task. One must remember that the activities of UGRR participants was illegal according to Section 7 of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Consequently, primary source evidence of UGRRs is often scarce. In rare instances, someone like prominent Hoosier abolitionist Levi Coffin might leave a record of their involvement. Some times there may be court cases that document UGRR activity. Yet, in most cases, knowledge of UGRR participation passes into memory and tradition, which is less reliable than contemporary documentary records.

In 1958, Wabash College history professor and Montgomery County, Indiana historian Theodore G. Gronert made the following assessment of the historical records:

The Wabash Valley members of the Underground left no detailed records such as those made by . . . the Whitewater Valley antislavery group. When participants and observers, some years after the event, told the story of the Underground Railroad, there was a natural tendency to embroider the story with fanciful details or even to recall events that never happened. . . . Unfortunately our source material for the contribution of Montgomery County to the Underground Railroad is limited. Only a few scattered reminiscences, some vague references in contemporary newspapers . . . are available to those who desire a record of the county’s part in this dramatic episode in the nation’s history.

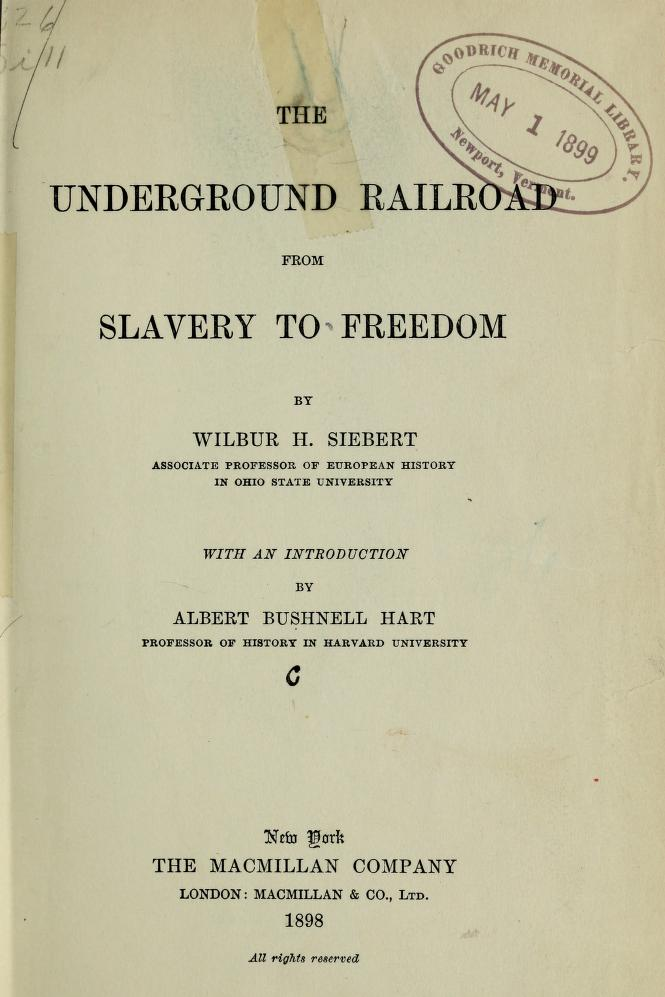

In the late nineteenth century, Ohio State University professor Wilbur H. Siebert embarked on a remarkable project to collect reminiscences of UGRR activity from a decreasing pool of living participants and their descendants. He wrote to residents all over the county in an attempt to document UGRR routes, participants, and incidents. When he identified informants who could give him first or second-hand information, he mailed questionnaires asking seven basic questions regarding: 1) the route through the area; 2) the years of activity; 3) the system of communication between conductors; 4) memorable incidents; 5) the informant’s personal connection with the UGRR; 6) names and addresses of any potential additional informants; 7) a biographical sketch of the correspondent or the chief UGRR participant in the area.

Siebert’s research culminated in The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom published in 1898. Among the thousands of letters he collected, he deemed one incident that occurred in Montgomery County, Indiana to be especially noteworthy, and he included an extract of the letter in his book. The critical reader is always interested in an author’s sources. Fortunately, Siebert’s research archive survives today at the Ohio History Connection. Within that archive is a typescript of the entire letter that Siebert quoted in his book. Written by Sidney Speed in 1896, the letter is the most interesting, detailed, and closest thing to an extant primary source concerning UGRR activity in Montgomery County. A transcript of the letter with added annotations and commentary is below.

EDITOR’S NOTE: As a word of caution to readers, Speed uses a racial slur to describe African Americans several times in his letter. While the Indiana Historical Bureau does not condone the use of this word, it is part of the historical record.

Letter from Sidney Speed[1] to Wilbur H. Siebert

Crawfordsville, Ind. March 6, 1896

W. H. Siebert

Cambridge, Mass.

Dear Sir:

Replying to your circular[2] of March 1. The old time abolitionists of this section are now all, or nearly all, dead. Twenty years ago it would have been easy to gather the information you want, but now I am afraid you are everlastingly too late. I was only a boy and do not remember much of interest.

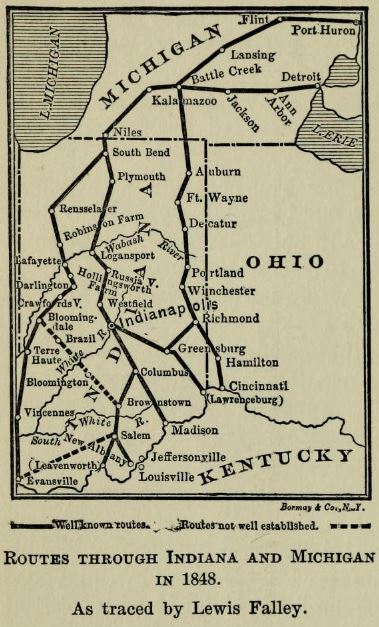

The route traveled by the fugitive slaves and those conducting them was from Annapolis (now Bloomingdale), a Quaker settlement in the north western part of Parke Co. to this place and for sometime [sic] this place was the terminus of the Underground proper, as at this place the fugitives were supplied with money, and put on board the car of the old L. N.A. & C. road[3] (now the “Monon”)[4] whose Management was then friendly, and were safely run through to Detroit,[5] and over the river.[6] Afterward however the conditions were much changed on account of the great number of spies and nigger catchers that sprung up for the rewards to be earned. Then the line of the Underground railroad was extended from this place through the Quaker settlement near Thorntown, Boone Co., and had its terminus at or near Noblesville in Hamilton Co. and it may have been extended farther than that afterward.[7] But of that I do not know.

The main men connected with the road here [in Crawfordsville] was Mr. Fisher Doherty,[8] and my father John Speed.[9] They were often assisted financially and personally by others who were never known as abolitionists. Notable among these was Major I. C. Elston[10] a banker of this place and a staunch and life long democrat who always contributed something and would say “I don’t want to know what you are doing” “go away.” An old Virginia slave named Patterson[11] was also of great service. His wife[12] had bought him in Virginia. She was born free, and I remember that when she would become angry at “old Pat” as we all called him, she would threaten to take him back south and sell him. Calling him at the same time her “old pumpkin colored nigger.” She was black herself. [13] I think he was used as a guide, and watchman.

Sometimes the fugitive negroes were brought to this place, in the night generally, by a man named Elmore, who lived between this place and Annapolis – (near Alamo this county) [14] and sometimes Mr. Doherty or my father would go and bring them. Sometimes Mr. Doherty or my father would go on from here to the next stopping place with them, but often an old Quaker named Emmons[15] who lived six or eight miles north east of here would come after them. I remember yet his kind old solemn face, and his old farm wagon covered with black oil cloth with some old hickory bottomed chairs, and pots tied on the feed box behind, and a brindle bull dog under the wagon, just behind the driver’s seat a sheet was drawn across and in the interior was seats down the sides that would accommodate [sic] ten or twelve nicely. He usually came to our house soon after dark, and at once taking in his cargo sometimes from the house, and sometimes from the cornfields or woods, he would start out for the next station. Somewhere near Thorntown, which he would reach and return to his own home before daylight.[16]

- My recollections of the period of activity of the road was from about 1854, when I was eight years old to 1863,[18] when I was sixteen years old, and enlisted in the 18th Ind. Battery.[19]

- I have no knowledge of the system of communication between members.[20]

- At one time in 1858, or 1859, a mulatto girl, about eighteen or twenty years old, and very good looking and with some education had reached our house, when the nigger catcher became so watchful that she could not be moved for several days.[21] In fact for some days some of them were nearly always at the house either on some pretended business or making social visits. I do not think that the house was searched, or they would surely have found her, as during all this time she remained in the garret over the old log kitchen, where the fugitives were usually kept, if there

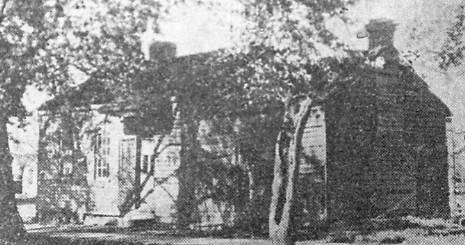

The Speed’s home was located on the southwest corner lot of North Street and West Street (today Grant Street) in Crawfordsville. Although the home no longer stands, the log kitchen that Sidney Speed describes is on the right end of the photo. The Speed Cabin, as the kitchen portion is known today in Crawfordsville, is preserved on the grounds of the Montgomery County Historical Society’s Lane Place. Image from Crawfordsville District Public Library Reference Department Image Database. was danger. Her owner, a man from New Orleans, had just bought her in Louisville, and he had traced her surely to this place she had not struck the Underground before, but had made her way alone this far, and as they got no trace of her beyond here they returned here and doubled the watches on Doherty and my father, but at length a day came, or a night rather, when she was gotten safely and through the gardens to Nigger Patterson. Then she was rigged out in as fine a costume of silk and ribbons as it was possible to procure at that time, and was furnished with a white baby borrowed for the occasion, and accompanied by one of the Patterson girls (Mariah I think was her name)[22] as a servant and nurse, she boldly boarded the train at the station and got safely through to Detroit. But what must her feeling have been when she board the train to find that her master or owner had already got on the same car. However she kept her courage and [he] did not discover her identity until the gang plank of the ferry boat at Detroit was being hauled aboard, and the Patterson girl with the borrowed baby had returned to the shore when she removed her veil that he might see her and bade her owner goodbye. That this parting was affecting you can imagine. He tried to wreck his vengeance on the Patterson girl, but was restrained by strong hands. There were usually plenty at Detroit.

- My own connection with the Underground Railroad consisted in trying in common with the other members of the family to get enough victuals into the house to feed the hungry without creating suspicion.[23]

Indiana Centennial Celebration Pageant in 1916 in Montgomery County where the citizens re-enacted the incident with Allred the butcher. Photo from Crawfordsville District Public Library Reference Department. - Mr. T. D. Brown[24] of this place, who was a contributor to the cause can tell you a good story of how the Allens of Browns Valley,[25] once caught a fugitive slave and brought him to town for identification, and stopping in front of the hotel, they went in to examine the “runaway nigger notices” leaving the negro holding the horse, and how old man Alred,[26] who had a butcher shop next door, picked up a dornick[27] or two from the street and ordered the nigger to “git.” (and he got, and to a place of safety too) and how Alred threw a rock into the hotel after the Allens and following it in himself was soon in a fine quarrel with them, which continued only until the nigger was safe.[28] (Make Brown tell you the story.)

Mr. Doherty’s wife Isabel Doherty is living,[29] and could likely help you [with more information].

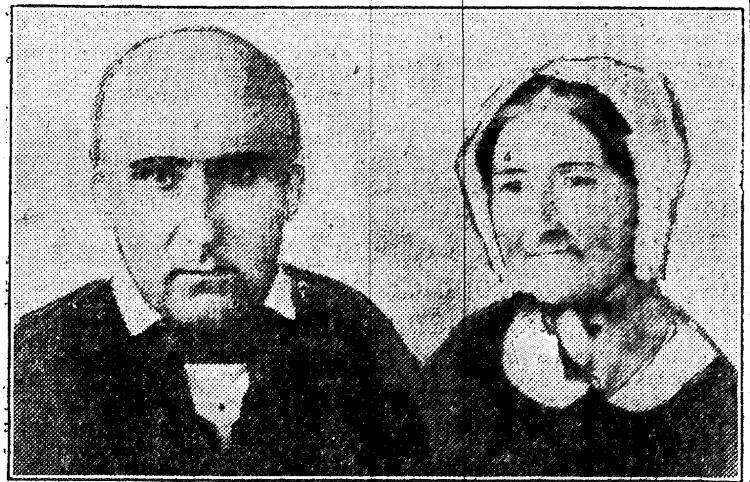

- My father John Speed was born in 1801. He was the twelfth and youngest child of his father’s family who was a small land owner and miller in Perthshire, Scotland. My father came to America in 1823, and was employed at his trade, Stone cutter and Mason in building dry docks, and other government work at or near Washington D. C. He came to Indiana with a contract to build the first state house at Indianapolis, Ind.,[30] but subsequently threw up the contract because the commissioners would not use stone that he thought suitable, but persisted in using a species of shale, which is abundant there, and which soon giving way caused no end of trouble[31] until the building was finally replaced by our present Magnificent structure.[32] He shortly after this contracted to build the part of the National Wagon road from Indianapolis to St. Louis.[33] During the building of the road [P]resident Jackson “busted the banks”[34] and the contract fell through, and “busted father” because the government had no money with which to either pay or continue. He then returned to the east on foot, going by the way of Cumberland Gap – leaving his family here. He built the present State House at Raleigh North Carolina[35] – returning here he ended his days living true to his conception of right. He was elected twice Mayor of this place,[36] and died in 1873 universally respected for his honesty and integrity.

Hoping that you may find something in this that may assist you, but fearing that it will all be useless I am.

Yours Very Truly

Sidney Speed.

[1] Sidney Allen Speed (1846-1923) was the son of John and Margaret Speed. He attended Wabash College for a few years before the Civil War, served in the 18th Indiana Artillery, and later became a stone mason. Some of his stonework includes Lew Wallace’s grave obelisk, which measures 30 feet in height, located in Oak Hill Cemetery North in Crawfordsville, Indiana.

[2] The circular is in reference to Siebert’s seven-question survey.

[3] The Louisville, New Albany, & Chicago Railroad originally started as the New Albany and Salem in 1847. By 1854, the line extended from the Ohio River to Lake Michigan and Chicago.

[4] The railway became popularly known as the Monon after the L. N. A. & C. consolidated with Chicago and Indianapolis Airline Railroad Company in 1881. The junction of these two routes in White County was near two creeks named the Big Monon and the Little Monon. The extant town at the junction, New Bradford or Bradford, was renamed Monon.

[5] The Monon did not run to Detroit, so freedom seekers would need to transfer at some point in northern Indiana or go into southern Michigan.

[6] The Detroit River which is part of the border between the United States and Canada.

[7] The map published in Siebert’s Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom differs from Speed’s recollection the Wabash Valley route heading northwest from Thorntown to Lafayette and northerly from there. The map traces a central route through Indiana from Madison to Columbus to Indianapolis through Westfield in Hamilton County, and through Noblesville and points north.

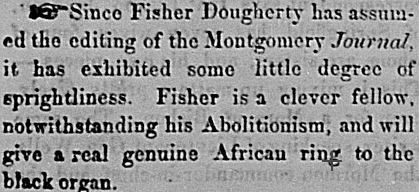

[8] Fisher Doherty (1817-1890) according to his obituary in the Crawfordsville Weekly Journal settled in Crawfordsville in 1844. He is listed in the 1850 U.S. Census as a carpenter, and in the censuses thereafter as a wagon or carriage maker. His obituary stated, “He was one of the original and most uncompromising Abolitionists all over the State. Crawfordsville became one of the main stations of the underground railway and Mr. Daugherty’s [sic] house was the stopping place of all runaway slaves struggling toward Canada. He is said to have assisted hundreds on their way and spent much time and money most cheerfully in this manner.”

[9] John Speed (1801-1873) was a native of Scotland and a stone mason by profession. He served as mayor of Crawfordsville from 1868-1870. Sidney Speed gives a fuller biography of his father later in this letter.

[10] Isaac Compton Elston (1794-1867) was a merchant and banker. He was by most accounts the wealthiest man in Crawfordsville. He had a large family, and his daughter Joanna and Susan were married to U.S. Senator Henry S. Lane and Ben-Hur author Lew Wallace, respectively.

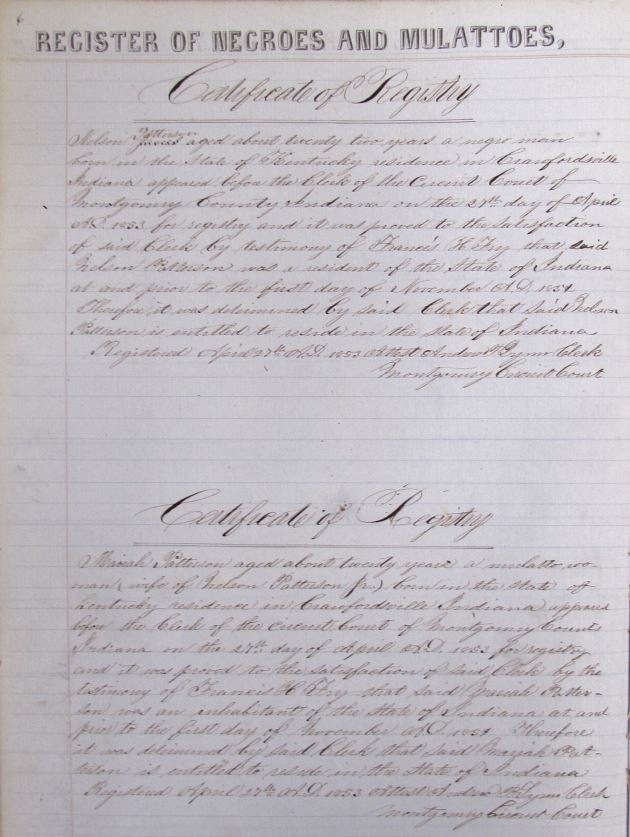

[11] Based upon Speed’s description, this was Nelson Patterson, senior. Patterson (1786/90-?) was born in Virginia. The 1850 U.S. Census recorded him as a laborer, and the 1860 census listed him as a brewer. The Patterson family is listed in the 1850 census as living next to the Speeds. Among the seven children listed with him in the 1850 U.S. Census was a son also named Nelson (circa 1828-1873). The son served in the 28th U.S. Colored Troops during the Civil War.

[12] Martha Patterson is listed in the 1850 and 1860 censuses as being born in either 1797 or 1790. Her place of birth is recorded as Virginia.

[13] Both the 1850 and 1860 censuses described Nelson Patterson as a mulatto. Martha Patterson is described as black in the 1850 census.

[14] According to the 1903 book, Twenty-five Years in Jackville: A Romance in the Days of the Golden Circle by James Buchanan Elmore, the author identifies Thomas Elmore as being involved in Underground Railroad activities in and around Alamo. Thomas was the uncle of the book’s author. Thomas Elmore (1816-1879) was an Ohio-born farmer. In 1856, he served on a Ripley Township Republican committee in Alamo that called slavery “the greatest evil of the nation.” The committee also resolved to make no compromises with the South on the slavery question.

Although Twenty-five Years in Jackville contains some historical and factual errors, James B. Elmore does list several other UGRR operatives in and around Alamo and Ripley Township. Among the names he associates with UGRR activity are: Hiram Powell, Joab Elliott, William Gilkey, Dr. Iral Brown, and Abijah O’Neall at Yountsville.

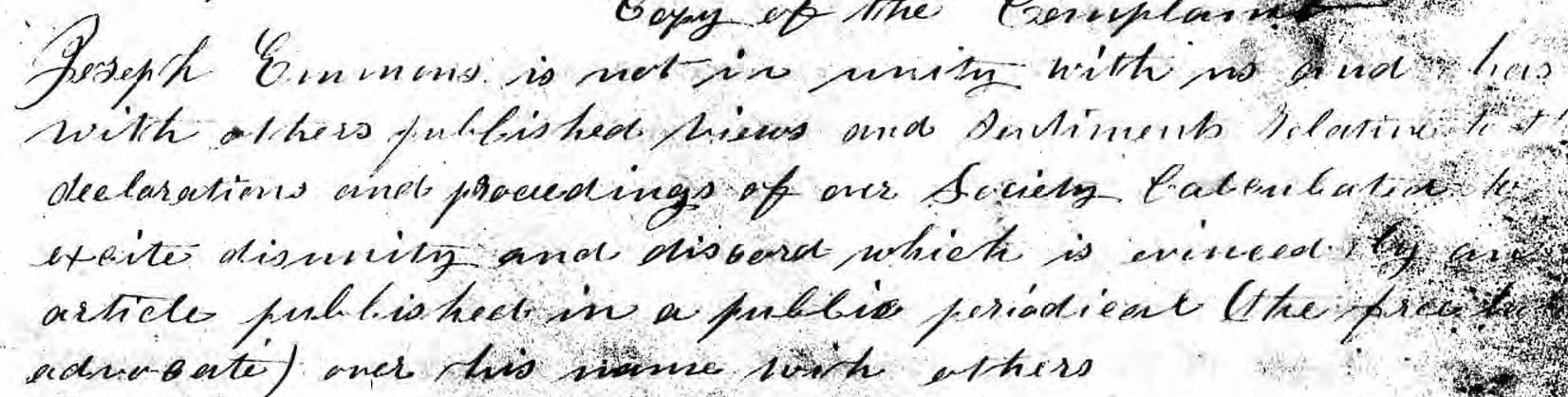

[15] Joseph Emmons (1812-1880) was a physician, and an active member of the Sugar River Monthly Friends Meeting. He lived in rural Montgomery County near Binford, which is currently the unincorporated community of Garfield.

Emmons’ involvement in the UGRR was also attested to by Siebert correspondents in Bloomingdale and Darlington, which were on both ends of the line through Montgomery County. Because Emmons’ involvement in the UGRR was so widely acknowledged by Siebert’s informants in the area, it suggests that he was a central actor in ferrying African Americans through Montgomery County.

[16] In 1896, long-time Darlington physician Isaac E. G. Naylor wrote to Siebert that “Alexander Hoover a Methodist, Joseph Emmons and Hudson Middleton – Quakers” were the principal “superintendents” along the branch passing through Franklin Township area including Binford, Darlington, and through to Thorntown.

Emmons’ medical profession could have presumably given him a plausible pretense for traveling at dusk or night if stopped by authorities or bounty hunters.

[17] As for contemporary evidence of African American freedom seekers traveling through the county solo: On August 16, 1855, the Crawfordsville Journal reported on an incident when a couple of hunters stumbled across a black man along a creek in the southern part of the county. After questioning the man, the hunters threatened to apprehend him as a fugitive. The man tried to escape, but ended up drowning.

[18] This statement is in response to Siebert’s second question on the questionnaire regarding the period of activity.

[19] The 18th Indiana Battery of Light Artillery was also known as Lilly’s Battery after their commanding officer Eli Lilly, who later founded a pharmaceutical company. The battery participated in battles at Hoover’s Gap, Chickamauga, and General William T. Sherman’s campaign against Atlanta.

[20] This statement is in response to Siebert’s third question about how Underground Railroad conductors communicated with each other.

[21] Here Speed related this memorable incident in response to another Siebert query.

[22] Mariah is likely one of two people. The Pattersons’ daughter, Almira, would have been in her late-teens or early twenties around this time. Another possibility is Mariah Patterson, who was married to Nelson Patterson, junior. Mariah would have been about twenty-seven or twenty-eight at the time, but she also had several young children, which makes her participation in the escape less likely.

[23] In a biographical sketch about John Speed, presumably provided by Sidney or another child, printed in Hiram Beckwith’s History of Montgomery County offers a few more details regarding this activity: “At one time the garret [of the house] was so full [of freedom seekers] that to prevent suspicion that he [John Speed] was harboring anyone he bought twenty-five cents’ worth of bread, then required his children to purchase a like amount each, until he obtained sufficient food for his attic visitors.”

[24] Theodore Darwin Brown (1830-1916), according to his obituary, settled in Crawfordsville in 1844, and worked for decades as a druggist. He also served as county clerk. Also according to his obituary, Brown was “an uncompromising Republican” who inherited his political views from his father, Dr. Ryland T. Brown, “one of the early abolition leaders of the state.”

[25] Enough information is not given to conclusively identify the Allens. According to the U.S. censuses, there were several Allen families residing in Brown Township in the 1850s.

[26] This probably refers to James Allred or Alred (1784-?). Allred, a native of North Carolina, appears in the 1840 and 1850 censuses as residing in Montgomery County. In the 1860 census, he is listed in Marion County.

[27] “Dornick” is an arcane word meaning a small pebble or stone.

[28] According to an 1898 article in the Crawfordsville Review the incident described took place in 1848. The article also offers some other particulars, like Allred’s first name.

[29] Whether Speed wrote the name wrong, or Siebert transcribed it incorrectly, Fisher Doherty’s wife was Sarah Owen Doherty (1820-1901). Her obituary notes Fisher Doherty as “a prominent promoter of the underground railroad, harboring many a runaway negro in his home. Mrs. Doherty was devoted to him thoroughly in his work and was a woman liberally endowed by nature of a great force of character.”

[30] Indiana’s first state house in Indianapolis opened in 1835.

[31] The construction of the building was problematic, and included the collapse of the House Chamber ceiling in 1867. A legislative committee began studying replacing the building in 1873, with a plan finalized in 1878.

[32] Construction on a new state house began in 1878, and continued until 1887/88. This building still serves the Indiana State Capitol.

[33] The National Road was the first interstate highway built with federal funds. Construction began in Cumberland, Maryland in 1811. Federal funds for the road ended in 1838 while construction was still being done in Indiana.

[34] President Andrew Jackson vetoed a bill in 1832 to re-charter the First Bank of the United States. Jackson reasoned that the Bank was not authorized by the Constitution, and “subversive to the rights of States, and dangerous to the liberties of the people.” Jackson took further steps to weaken the Bank when he decided to place federal funds on deposit in state banks. The Bank’s charter expired in 1836, and contributed to a major economic recession (some sources say depression) that lasted until the mid-1840s.

[35] The North Carolina State Capitol was completed in 1840.

[36] Speed was Crawfordsville’s second mayor. He served from 1868-1870.