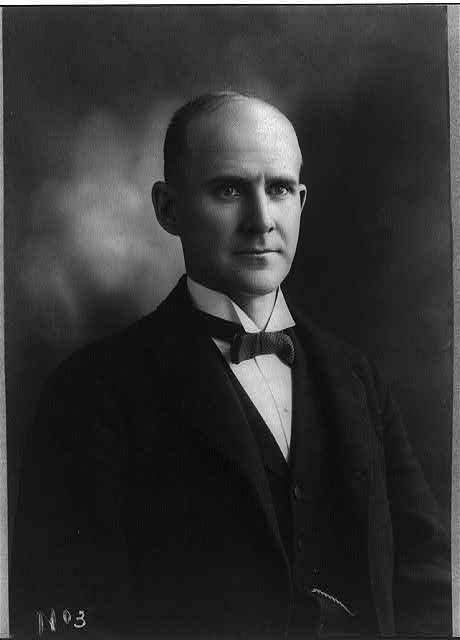

During his long and storied career, Indianapolis-based investigative journalist William H. “Billy” Blodgett exhibited a penchant for exposing local corruption and unlawful business practices. One not entirely aboveboard business in particular caught his attention in the 1890s.

During the Gilded Age, bicycles became a national phenomenon. With ever-changing designs and the lowering of costs, bicycles spurred social clubs, faced religious blow back, and even influenced clothing trends. As such, the need for bicycles exploded, with hundreds of different companies competing for their share of the marketplace. There were dozens of companies in Indiana alone.

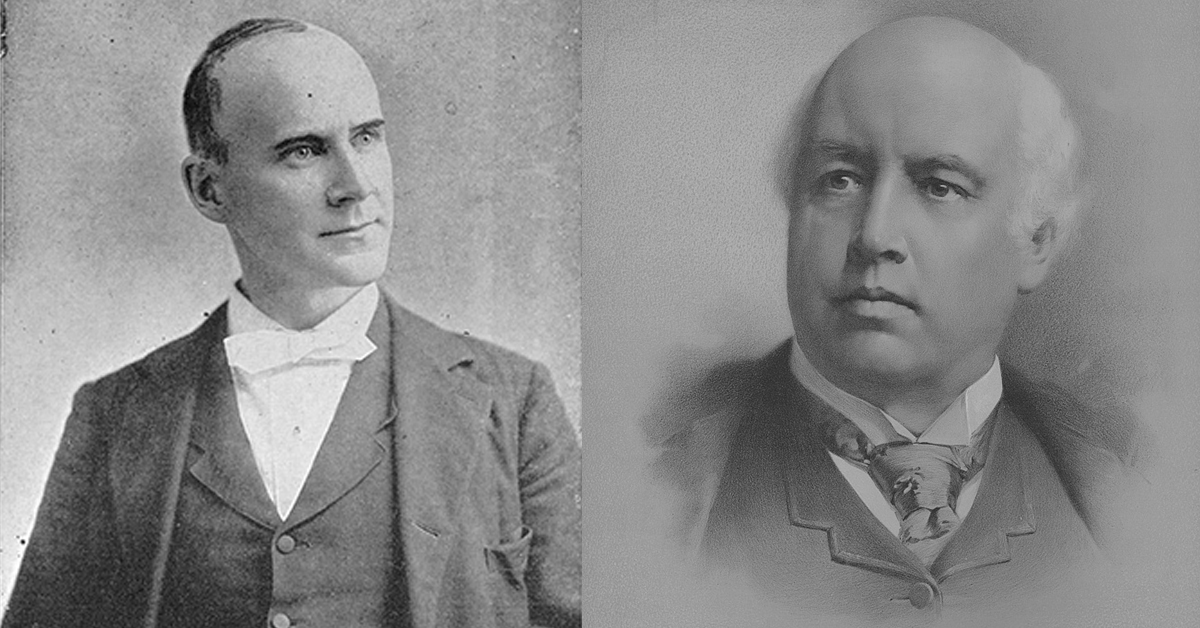

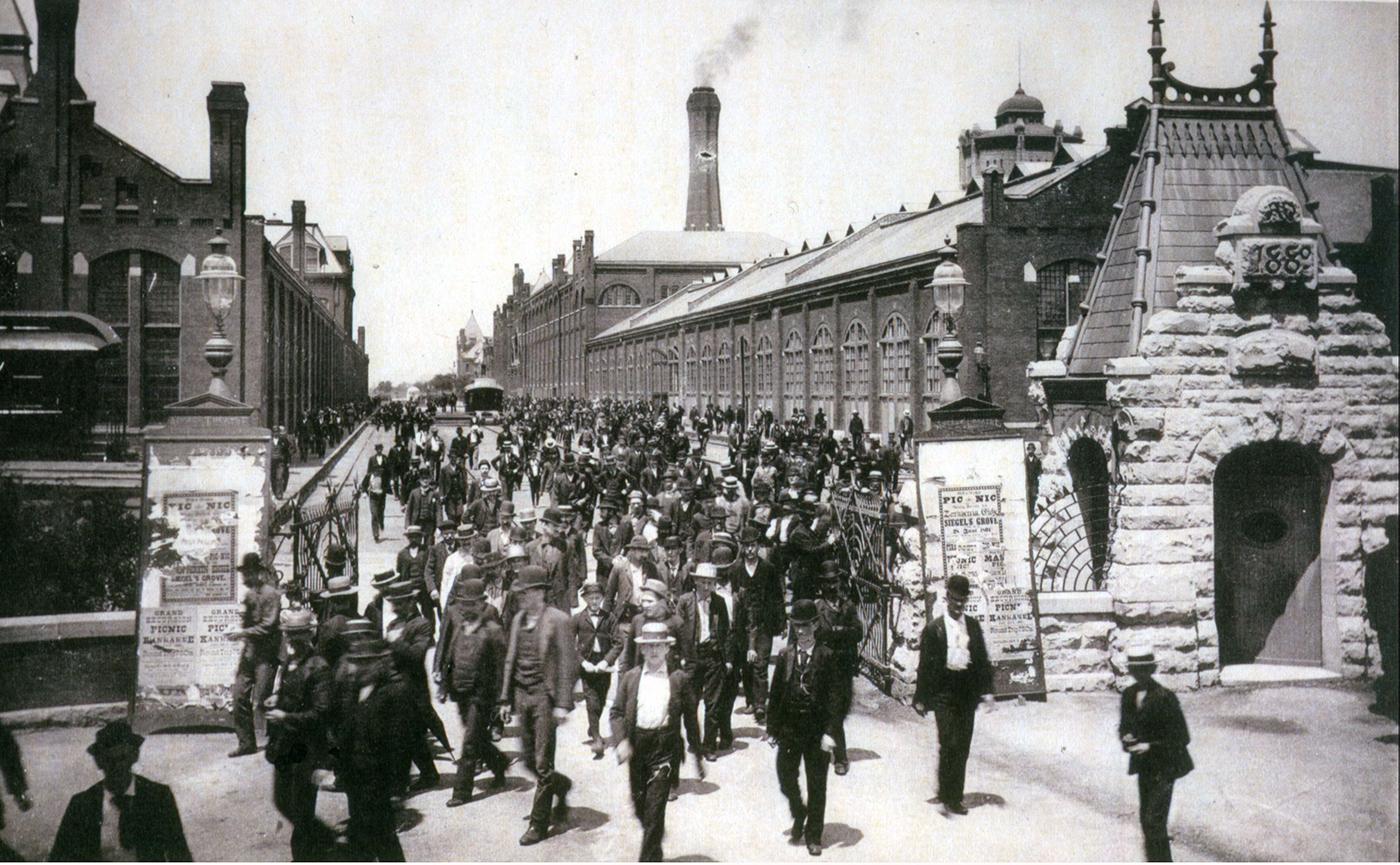

Of these companies, the Allen Manufacturing Company garnered moderate success but attracted controversy. Founded in 1894 and later incorporated in 1895 by David F. Allen, David A. Coulter, James Murdock, and William B. Hutchinson, Allen Manufacturing maintained a peculiar corporate structure and political affiliation with the Democratic party. In some respects, you could have called the company a “Government-Sponsored Enterprise,” wherein the products made were sold in the marketplace but the labor and capital costs were funneled through government institutions. This is especially true of its labor force, comprised exclusively of prisoners from the State prison north in Michigan City. As reported by the Indianapolis News, “the convicts who work in the factory are to be paid 42 cents a day. Mr. French [the prison’s warden] says that 150 men will be employed in the factory.”

Before Blodgett’s investigative reporting on the company, the Indianapolis Journal published a pointed critique of Allen Manufacturing’s labor force. The piece referred to the venture as a “blow to honest labor” and argued that the lack of skilled bicycle makers will “glut the market with cheap wheels.” The article emphasized this point in a further passage:

At the price paid [for labor] the company will have a great advantage over the manufacturers of Indiana, and their employees will, of course, share in the loss by reason, if not through cheapened wages, then of less opportunity for work. The new venture is not likely to decrease their hostility to the prison labor system and the Democratic party of Indiana.

Another piece in the Indianapolis News, possibly written by Blodgett, also criticized the company’s deep ties to political operatives, and in particular, founder David F. Allen. Allen was serving on the State Board of Tax Commissioners when the company was founded (but not incorporated), and if he didn’t leave the Board, he would be violating section 2,049 of the Indiana legal code. In other words, Allen and his business partners kept the public existence of the company private for nearly a year, incorporating on March 14, 1895, so as to avoid potential conflicts of interest.

While Allen Manufacturing was still an unincorporated entity, it struck a deal with the Indiana prison north in October 1894 to employ 150 prisoners at forty cents a day (lower than forty-two cents, as mentioned in the papers) for the next five years. The agreement was then amended in 1896 to remove twenty-five workers from the contract for another project. Again, this is a private consortium of well-connected political operatives setting up a business to take advantage of the state’s prison labor system .

At least the prisoners made a quality product. While I couldn’t find photographs of the bicycles, they were apparently made well enough to appear in a state-wide bicycle exhibition on January 28, 1896 at the Indianapolis Y.M.C.A. According to the Indianapolis Journal, the Allen Manufacturing Company displayed its bicycles with 14 other firms and the show also displayed artwork by T.C. Steele, among others. Allen Manufacturing also acquired the Meteor Bicycle Company, a nationally recognized firm located in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and began manufacturing bikes under the name from 1896 to 1898. While the public face of their company seemed bright, its internal workings quickly began to unravel.

By 1897, Allen Manufacturing’s financial problems began bubbling to the surface. After the release of twenty-five prisoners from their contract at Indiana state prison north, its labor force wasn’t big enough to keep up with an order for 2,000 bicycles wheels. From there, the company ran up debts that were nearly impossible to reverse, taking out a mortgage to offset their losses. As reported by the Indianapolis News:

Edward Hawkins, of this city [Indianapolis], who has been appointed trustee under the mortgage, returned to-day from a meeting of the officers and directors of the company at Michigan City. The company, he says, found itself unable to pay its paper due, and executed a mortgage on the plant for the benefit of the banks that hold the paper.

Even though it paid off $6,500 owed to the state in October of 1897, Allen’s troubles continued. Hawkins was removed as mortgage trustee, more and more creditors were filing claims, and two court-appointed receivers stepped in to try to clean up the mess.

This is where Billy Blodgett’s articles began to shed light on the corruption. In January of 1898, Blodgett began a series of hard-hitting exposes in the Indianapolis News against Allen Manufacturing, writing of alleged abuses of state power, graft, and fraud. His first article, published on January 13, 1898, alleged that whole train-cars of bicycles were purchased by individual owners of the company, such as D. F. Allen and D. A. Coulter, and then shuffled around the assets for accounting purposes. Specifically, Allen purchased “$4,000 worth of bicycles,” transferred ownership to his son, and then “applied [the amount] on notes given to the Merchants’ National Bank of Lafayette.” The article also reaffirmed what many had suggested since the company’s founding. Namely, its public incorporation was made after key leaders removed themselves from conflicts of interest yet acted as an incorporated entity when it negotiated its labor contract with the prison.

The next day, Blodgett published the next installment, writing of the company’s alleged fraud in connection to its stocks. The Chicago firm Morgan & Wright, who purchased the company’s manufacturing plant during its initial financial woes, alleged that Allen Manufacturing had used backdoor loans from the Merchant’s National Bank of Lafayette in order to inflate its asset value. “In other words,” Blodgett wrote, “Morgan & Wright will try to show [in court] that the total amount of money paid for the stock was $300,” rather than the $4,000 or $5,000 the company claimed.

Blodgett also reported another fascinating case of company misdirection. On October 15, 1897, LaPorte County Judge William B. Biddle ordered the company to stop selling any products and hand the reins over to receiver Alonzo Nichols. This order was ignored by Henry Schwager, another receiver appointed to the company in Michigan City. Biddle retaliated on November 23, issuing an order against the company at large and reaffirmed his previous decision. What came next is shocking:

. . . Sheriff McCormick went to Michigan City to take possession of the property. When he got there, he found the building of the Allen Manufacturing Company locked up, and he could not get in to make the levy, without using force. He was warned not to do this, so the sheriff and his deputies stood around on the outside of the prison, and as the carloads of property came out they seized them. He found the property at different points, and turned it all over to Nichols as receiver.

In other words, Sheriff N. D. McCormick and his deputies had to wait until the company didn’t think the authorities were looking before they could seize the goods. Even in the face of court orders, the Allen Manufacturing Company still tried to do things its own way, to disastrous results.

Billy Blodgett’s final big piece on Allen Manufacturing appeared in the Indianapolis News on January 15, 1898. In it, Blodgett tries to track down and interview company big-wigs David Coulter and David Allen. Blodgett wrote of Coulter that, “He is pleasant and affable, courteous and polite, but I might as well have talked to the Sphynx in Egypt, so far as getting any information from him.” Over the course of a short, frosty conversation between Blodgett and Coulter, the businessman declined to speak about any of the charges leveled against him and maintained his innocence. When Blodgett pressed him on some of the specific charges of defrauding investors, his “demeanor demonstrated that the interview was at an end. . . .”

As for Allen, he was unable to interview the man directly but spoke to one of his colleagues. Blodgett chronicled the exchange:

A few weeks ago Mr. Allen met this friend and said to him:

“You remember the evening you asked me to dinner with you in Chicago?”

“Yes, I remember.it distinctly.”

“Well, that failure to take dinner with you has cost me $5,000, and may cost me more.”

The friend understood from this that if Allen had not gone to the meeting at which the company was formed he would have been money ahead. This friend gives it as his opinion that every member of the Allen Manufacturing Company lost from $3,000 to $5,000 each.

In one corner, you have Coulter trying to hold things together and denying changes against him and Allen in the other allegedly remarking on how he and many others lost money. This inconsistency in the press didn’t help to make the public or the company’s shareholders feel any better about the situation.

By 1898, the company was defunct in all but name. Bicycles manufactured under the “Meteor” brand ceased and the company’s remains were being settled in numerous court cases. In 1900, a Louisville, Kentucky court ruled that Allen Manufacturing had in fact defrauded Morgan & Wright out of at least one payment for a shipment of product. Another lawsuit, clearing Sherriff Nathan McCormick of any wrongdoing against court-appointed receivers, was settled in 1901 in U.S. Court and upheld in the U.S. Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals in 1902.

Blodgett did write a follow up article in 1901, noting that Indiana state prison north Warden Shideler resigned over allegations that he was a stockholder in the company at the time he was serving as Warden. It also indicated that labor contract developed by Allen, Coulter and others in 1894 was binding until 1904, with other companies stepping in to fill the void left by the demise of the Allen Manufacturing Company. Newspaper evidence suggests that Allen, Coulter, and many of the other big players never faced serious charges and that the company’s multiple lawsuits distracted from the other allegations leveled against them. Allen himself would eventually pursue other political offices, including Indiana Secretary of State, as well as serve in the Spanish-American War. He died in 1911, with the failure of his company firmly behind him.

So what do we make of the Allen Manufacturing Company? In some ways, you can look at it as a quasi-private, quasi-public boondoggle, destined to fail. In other ways, you can look at it as a company created to enrich its leadership by taking advantage of sub-contracted labor. However, these may be the symptoms of a larger malady. The major take-away from this episode was that a rapidly changing industrial economy and a national fad in bicycles spurred a slapdash attempt to create a company that benefited from public connections. Furthermore, the episode highlights how determined and detailed journalism helps to keep the public and private sectors of society accountable, both to citizens and shareholders. While some of the key players never faced accountability, Blodgett’s success in investigating Allen Manufacturing’s corruption nevertheless exemplified how an individual citizen, and a free press, can check some of our more abject motivations.

![Instep-arch support patent [marketed as Foot-Eazer], Publication date April 25, 1911, accessed Google Patents](http://blog.newspapers.library.in.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/1911-Instep-Patent.png)

![Elevated Railroad Station at East Madison Boulevard and Wells Street [near Scholl's building] November 1, 1913, Chicago Daily News Photograph, Chicago History Museum, accessed Explore Chicago Collections, explore.chicagocollections.org/image/chicagohistory/71/qr4p14f/](http://blog.newspapers.library.in.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/train-station-at-Wells-and-Madison-CHicaho-History-Museum-300x243.png)