At the Indiana Historical Bureau, we routinely get requests from researchers for assistance. Some of these are fairly simple, like helping with someone’s family history or determining the age of an antique they just bought. However, every once in a while, we get queries so interesting that they require a whole lot more research, and you never know what you might turn up.

Back in March, I received an email from a gentleman in California who recently found a unique item while metal-detecting on the beach. He needed help figuring out what it was and how old it might be. It was a weathered, rusted emblem with two elephants on the front and a name, “Rub-No-More.” On the back, it said, “some worry about wash day; others use Rub-No-More.” He also knew it had an Indiana connection, as a quick internet search determined that the Rub-No-More brand was based out of Fort Wayne.

It turns out that the item he found was a Rub-No-More watch fob, likely made sometime between 1905-1920. A watch fob was a decorative piece that accompanied a pocket watch, and helped keep the watch in a wearer’s pocket. A fob exactly like this one was recently sold at auction. Chicago’s F.H. Noble & Company, whose long history includes making trophies and urns for cremated remains, manufactured the fob. But what about the history of the company who commissioned it, the Rub-No-More Company? In learning more about this small, weathered piece of advertising, I discovered a history of one of Indiana’s most successful businesses at the turn of the twentieth century.

While its origins go back at least to 1880, the Summit City Soap Works of Fort Wayne (the Rub-No-More Company’s original name) was formally incorporated in May of 1885, with a capital stock of $25,000 for “manufactur[ing] laundry and other soaps,” according to the Indianapolis Sentinel. Their penchant for lavishing gifts on customers goes back almost to its founding. As the Wabash Express reported on May 27, 1886, Harry Mayel of the Summit City Soap Works came to Terre Haute and provided “over one hundred and fifty thousand dollars in beautiful and valuable presents” to purchasers of the company’s Ceylon Red Letter Soap. While this was a great deal for consumers, it appears it wasn’t as good for the company. By 1888, the Summit City Soap Works was insolvent, with $18,000 in debt and only $14,000 in assets, and a court-ordered receiver came in to clean up the mess. The difficulties didn’t end there. Two years later, as mentioned by the Crawfordsville Daily Journal, the company’s facilities on Glasgow Avenue burned to the ground, an estimated loss of $6,000. The company, sadly, had no insurance to cover these damages.

Clearly, it was time for new leadership, and it came in the form of the highly successful Berghoff family, German immigrants who became a mainstay of Fort Wayne’s business community. The Berghoffs ran a profitable brewery in the city, most known for its “Dortmunder Beer” brand. They parlayed this success into other ventures, including the Summit City Soap Works. Gustave A. Berghoff, a traveling salesman for the brewery, purchased the soap manufacturer in 1892, likely from his own brother, Hubert. The latter had purchased the firm a year earlier for a measly $5,000, and intended to revive the soap maker to “run day and night,” according to the Fort Wayne Sentinel.

Gustave Berghoff and his team wasted no time getting the company back on its feet and profitable, betting its success on a brand new product, Rub-No-More. Introduced in 1895, Rub-No-More was a “labor saving compound” that “clean[ed] the working clothes of a mechanic as well as the finest linen of the household, without much rubbing,” the Fort Wayne News wrote in its May 30th issue. To kick off the new product, the company launched a massive advertising campaign that provided free samples of Rub-No-More to every family in Fort Wayne. Summit City Soap Works then sold it at five cents, in a package that would cover five washing weeks. Rub-No-More became a hit, greatly benefiting Berghoff and his company. As such, they continued their tradition of giveaways. For example, in 1898, Summit City Soap Works offered its customers a free children’s book or wall calendar in exchange for saved Rub-No-More coupons and Globe Soap wrappers.

The company completely reorganized in 1903, including a new incorporation and expansion of its facilities. After eighteen years as an incorporated company, the Summit City Soap Works saw its capital stock increase four fold, to $100,000. Its executive staff also evolved, with Gustave Berghoff retaining his position as president but appointing his brothers, Henry and Hubert Berghoff, along with J. W. Roach and Albert J. Jauch, to the board of directors. The Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette reported that Berghoff was “having built a large addition to his factory, which will double the plant’s capacity.” The paper also commented on the company’s success, writing that “the business has grown from a small beginning to large proportions, and the institution is now known all over the United States, and the output is used almost universally in this country.”

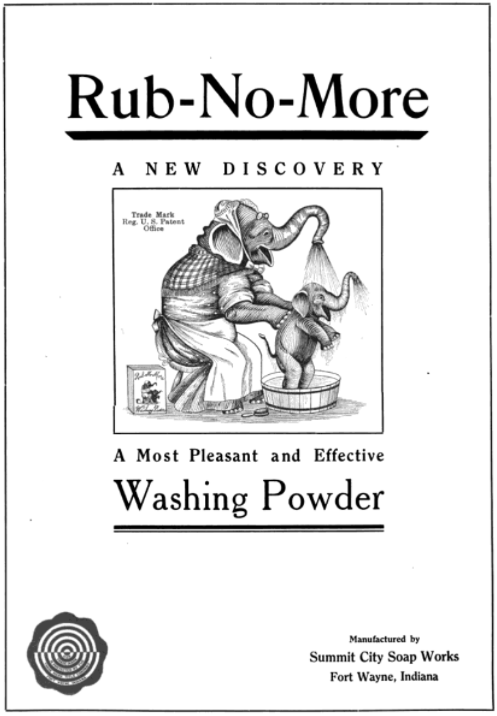

The company also expanded its marketing, filing for multiple trademarks in 1905. The first filing, from April 17, 1905, included its new logo for Rub-No-More as well as an emblem, one so iconic to the company that it inspired my research: the two elephants logo. Used for decades as the symbol of Rub-No-More, the trademark displays an adult elephant dressed as a washerwoman washing a child elephant with its trunk. The second filing, dated September 19, 1905, includes both the new logo for the company’s name as well as the two elephants symbol. These became the company’s go-to branding for both its products and promotional materials, and it served them well. Grocers at Kendallville purchased 14,000 pounds of soap from the company in April of 1909, as noted by the Fort Wayne Sentinel, which traveled “in a single shipment over the [city’s] interurban.” That year, the Summit City Soap Works continued its tradition of promotional giveaways. An advertisement in the Dayton Herald offered customers free gifts in exchange for some of their products’ packaging trademarks. They offered girls an embroidery set and boys a “very interesting game” suitable for thirteen people.

One incident in 1911 showed how Rub-No-More soap could lead to more than just fun giveaways. A young woman named Bessie Lauer, an employee of the Summit City Soap Works, wrote her name on the inside of a soap bar’s packaging. It made its way out west, where a “wealthy California orange grower” found it and sought out a courtship, perhaps even marriage. She turned down his offer, but the publicity it garnered led to a Hanford, California Sentinel article describing the whole affair. Apparently embarrassed by the incident, Lauer told the Sentinel that “this is the first time she has ever written her name on a soap wrapper, and she fervently states that it will be her last.”

After decades of operation under the Summit City Soap Works moniker, the company formally changed its name in 1912 to the Rub-No-More Company, solidifying the importance of their branded soap to the entire enterprise. (A notification of the name change was published in the January 18, 1912 issue of the Fort Wayne Daily News, but it wasn’t official until April 12, 1912, when articles of incorporation were filed, according to the Indianapolis News. Advertisements in newspapers as early as June of that year indicated the name change). Around this time, Gustave Berghoff, the company’s president, began serving on the board of directors of the German-American National Bank based in Fort Wayne, greatly increasing his stature within the local business community.

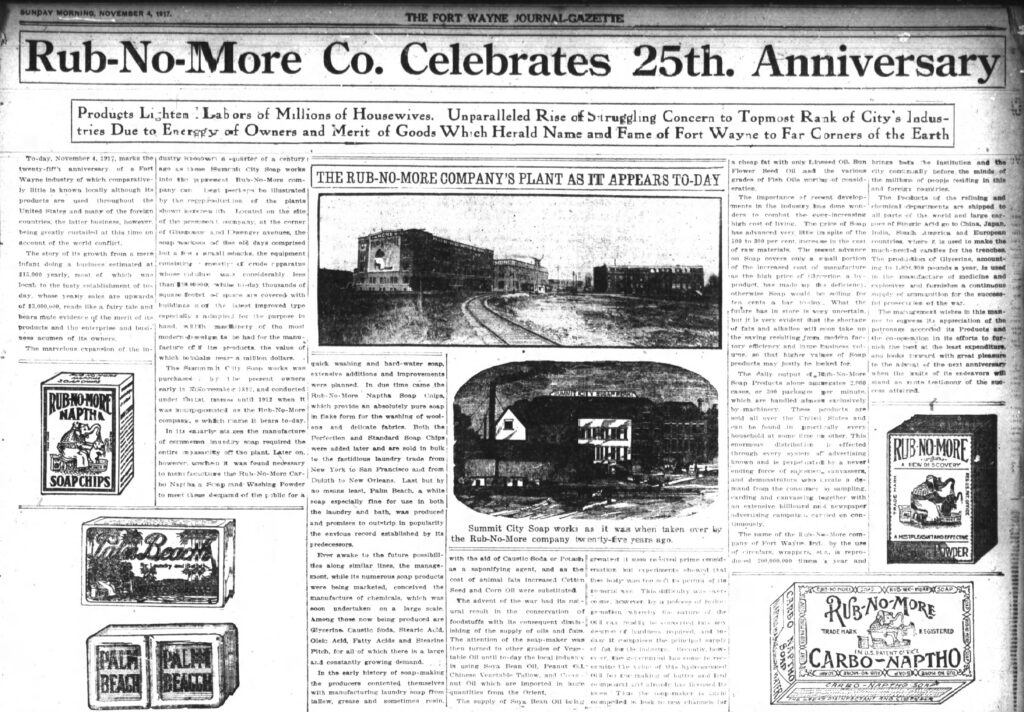

By 1917, sales of the Rub-No-More Company topped $3,000,000 a year, as referenced in a profile in the Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette celebrating its 25th anniversary under the ownership of Berghoff. The article noted the expansion of its production facilities, from “the old days [when the plant was] comprised [of] but a few shacks” with “equipment consisting mostly of crude apparatus[es],” to a plant comprising “thousands of square feet.” This machinery was “of the most modern design . . . the value of which totals near a million dollars.” Within two decades, Rub-No-More, the company’s flagship product, became a mainstay product for consumers, with “circulars, wrappers, etc. . . . reproduced 200,000,000 times a year,” bringing “both the institution and the city continually before the minds of millions of people residing in this and foreign countries.”

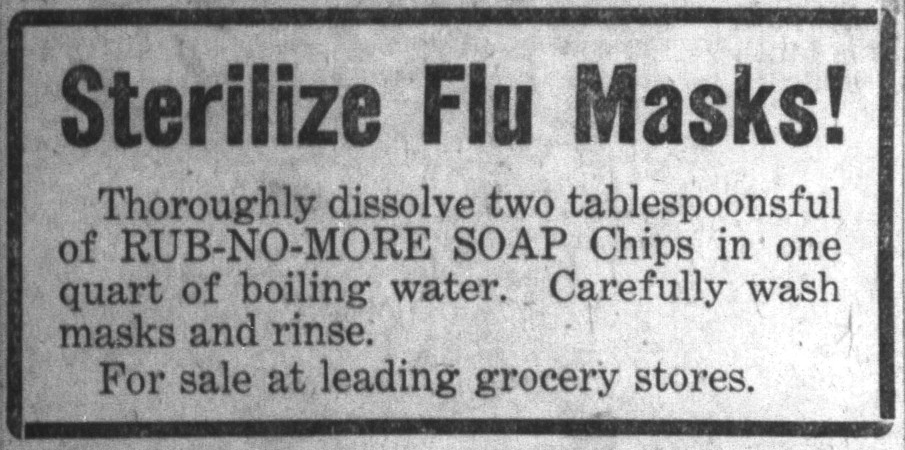

An interesting modern parallel, the Rub-No-More Company encouraged sterilizing face masks during the influenza pandemic of 1918. A notice printed in the November 22, 1918 issue of the Indianapolis News instructed readers to “sterilize flu masks” by “thoroughly dissolv[ing] two tablespoonsful [sic] of Rub-No-More soap chips in one quart of boiling water” to “carefully wash masks.” As with today’s COVID-19 pandemic, soap companies have used their advertising to encourage people to wear masks and to keep them clean, something the Rub-No-More company did over 100 years ago.

Despite the Rub-No-More Company having a mostly positive reputation, it wasn’t without controversy. In 1918, the Indianapolis Star reported that the Rub-No-More Company was one of several companies charged with violating the federal child labor law. In a grand jury indictment against them, it was alleged that “three children were required to work ten and one-half hours a day” at their plant. Another issue the company faced came from its manufacturing process— one of “obnoxious odors.” The Indianapolis Times wrote in 1923 that the City of Fort Wayne was seeking a “permanent injunction” requiring the Rub-No-More Company to reconfigure their production process to alleviate the harsh smells that bothered the city’s east side residents. It is unclear what the outcomes of these situations were, but violations of child labor laws and air quality, somewhat new to American industry in 1918, represented some of the lesser angels of industrialization.

After 35 years of success at the helm, Gustave Berghoff sold the Rub-No-More Company to Procter & Gamble and retired from the company in 1927. The company’s roughly 140 employees were transferred to other Procter & Gamble plants after a transitional period where Rub-No-More Company’s manufacturing stock was used. The Rub-No-More brand continued for many years under the Procter & Gamble umbrella, with advertisements for the product appearing in newspapers well into the early 1950s. Gustave Berghoff, the company’s former president, died on January 25, 1940 at the age of 76. He is buried in Catholic Cemetery in Fort Wayne.

The Rub-No-More Company exists in history as something of a Horatio Alger tale. A German immigrant, helped by his family, purchased a failing firm and turned it into one of the most successful soap companies of the early 20th century. Additionally, its innovative approach to marketing, promotions, and branding ensured its dominance in the marketplace. This story is also about how even a simple item, like a watch fob washing up on the beach in California, can lead to an understanding of one of northern Indiana’s industrial giants at the beginning of the American Century.