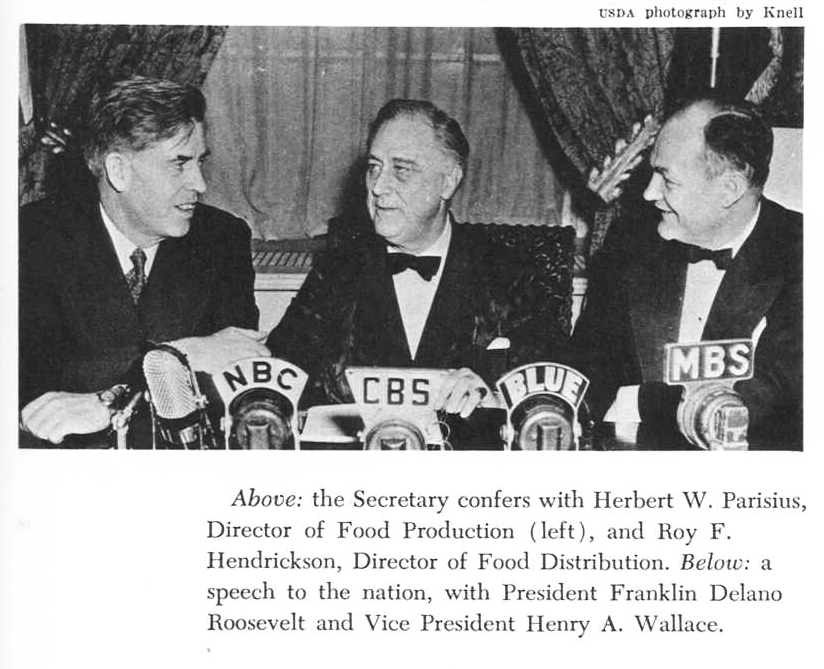

Describing the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt for the 2014 Ken Burns documentary The Roosevelts, conservative political writer George E. Will stated:

The presidency is like a soft leather glove, and it takes the shape of the hand that’s put into it. And when a very big hand is put into it and stretches the glove — stretches the office — the glove never quite shrinks back to what it was. So we are all living today with an office enlarged permanently by Franklin Roosevelt. [1]

Seventy-five years after President Roosevelt’s death, the debate continues over how much power the president should have, especially in regards to taking military action against a foreign power. On January 9, 2020, the U.S. House of Representatives voted to restrict that power, requiring congressional authorization for further action against Iran. The issue now moves to the Senate.

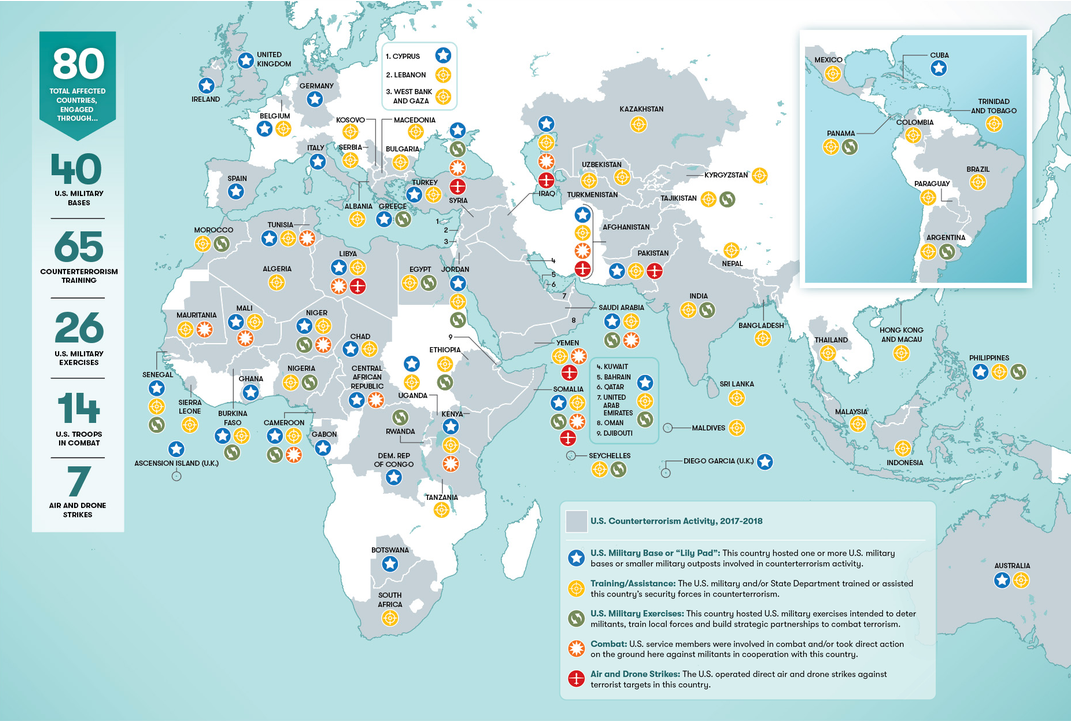

But the arguments over this balance of war powers are not new. In fact, in 1935, Indiana congressmen Louis Ludlow forwarded a different solution altogether – an amendment to the U.S. Constitution that would allow a declaration of war only after a national referendum, that is, a direct vote of the American people. Had the Ludlow Amendment passed, the U.S. would only engage militarily with a foreign power if the majority of citizens agreed that the cause was just. Ludlow’s ideas remain interesting today as newspaper articles and op-eds tell us the opinions of our Republican and Democratic representatives regarding the power of the legislative branch versus the executive branch in declaring war or military action. But what do the American people think, especially those who would have to fight? According to Brown University’s Cost of War Project, “The US government is conducting counterterror activities in 80 countries,” and the New York Times reported last year that we now have troops in “nearly every country.” [2] But what does it mean to say “we” have troops in these countries? And does that mean that we are at war? Do the American people support the deployment of troops to Yemen? Somalia? Syria? Niger? Does the average American even know about these conflicts?

Expanding Executive War Power

Many don’t know, partly because the nature of war has changed since WWII. We have a paid professional military as opposed to drafted private citizens, which removes the realities of war from the daily lives of most Americans. Drone strikes make war seem even more obscure compared to boots on the ground, while cyber warfare abstracts the picture further. [3] But Americans also remain unaware of our military actions because “U.S. leaders have studiously avoided being seen engaging in ‘war,’” according to international news magazine the Diplomat. [4] In fact, Congress has not officially declared war since World War II. [5] Instead, today, Congress approves “an authorization of the use of force,” which can be “fuzzy” and “open-ended.” [6] Despite the passage of the War Powers Act of 1973, which was intended to balance war powers between the president and Congress, presidents have consistently found ways to deploy troops without congressional authorization. [7] And today, the Authorization for Use of Military Force Joint Resolution, passed in the wake of the September 11 attacks, justified an even greater extension of executive power in deploying armed forces.[8]

“To Give to the People the Right to Decide . . .”

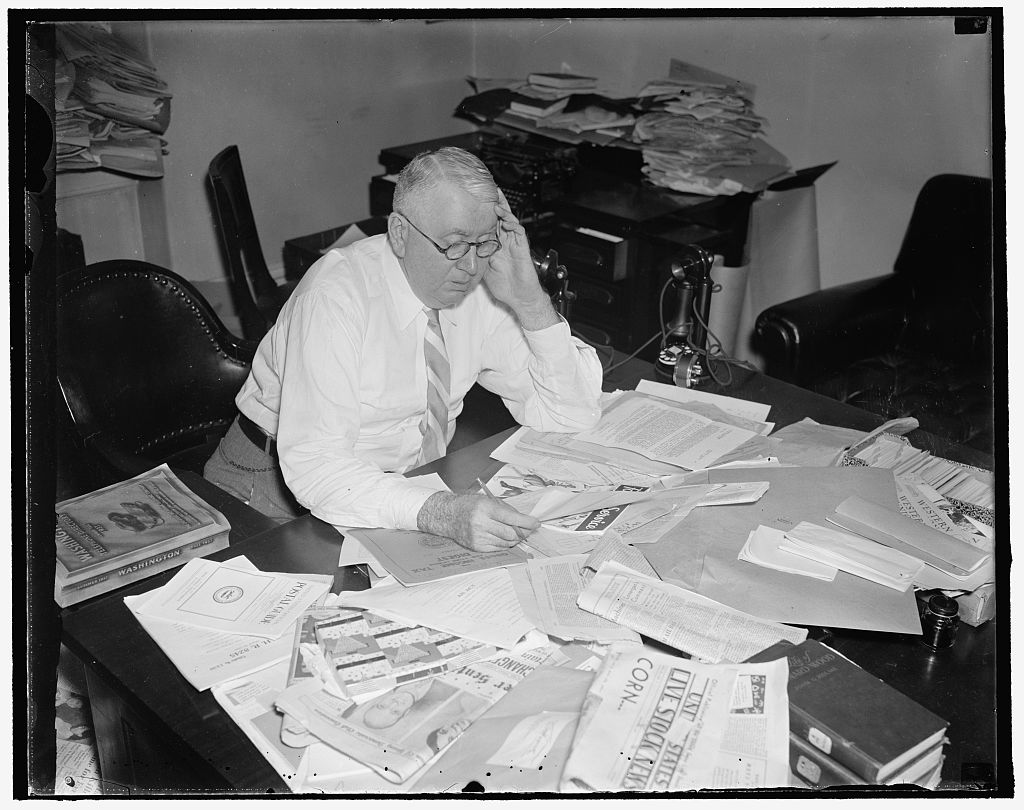

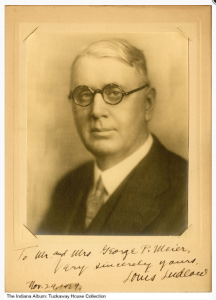

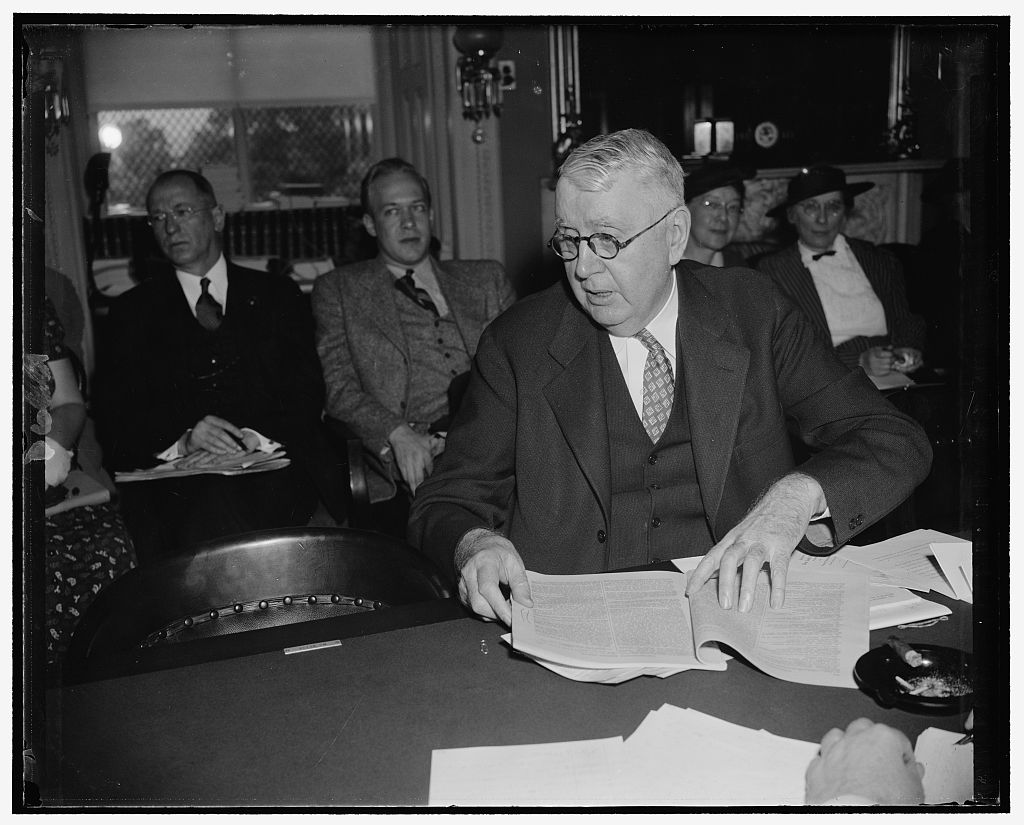

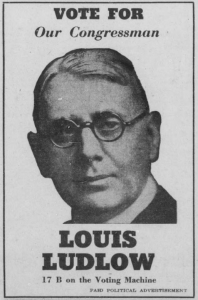

Indiana congressman Louis L. Ludlow (Democrat – U.S. House of Representatives, 1929-1949), believed the American people should have the sole power to declare war through a national referendum. [9] After all, the American people, not Congress and not the President, are tasked with fighting these wars. Starting in the 1930s, Representative Ludlow worked to amend the Constitution in order to put such direct democracy into action. He nearly succeeded. And as the debate continues today over who has the power to send American troops into combat and what the United States’ role should be in the world, his arguments concerning checks and balances on war powers remain relevant.

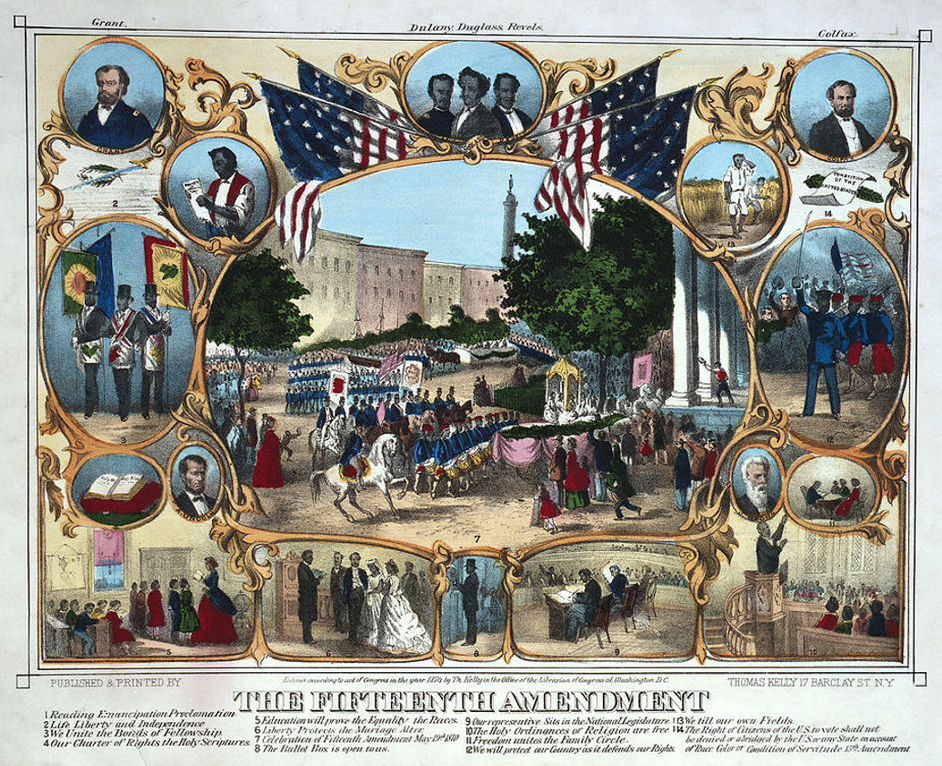

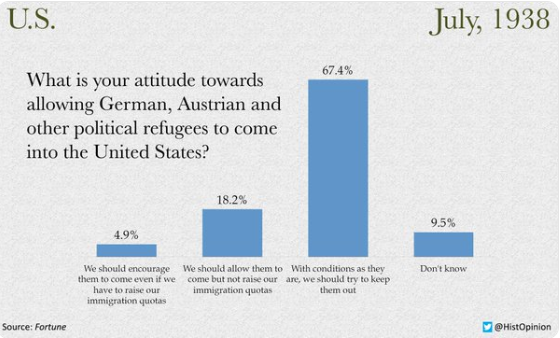

Ludlow maintained two defining viewpoints that could be easily misinterpreted, and thus are worth examining up front. First, Ludlow was an isolationist, but not for the same reasons as many of his peers, whose viewpoints were driven by the prevalent xenophobia, racism, and nativism rooted in the 1920s. In fact, Ludlow was a proponent of equal rights for women and African Americans throughout his career. [10] Ludlow’s isolationism was instead influenced by the results of a post-WWI congressional investigation showing the influence of foreign propaganda and munitions and banking interests in profiting off the conflict. [11]

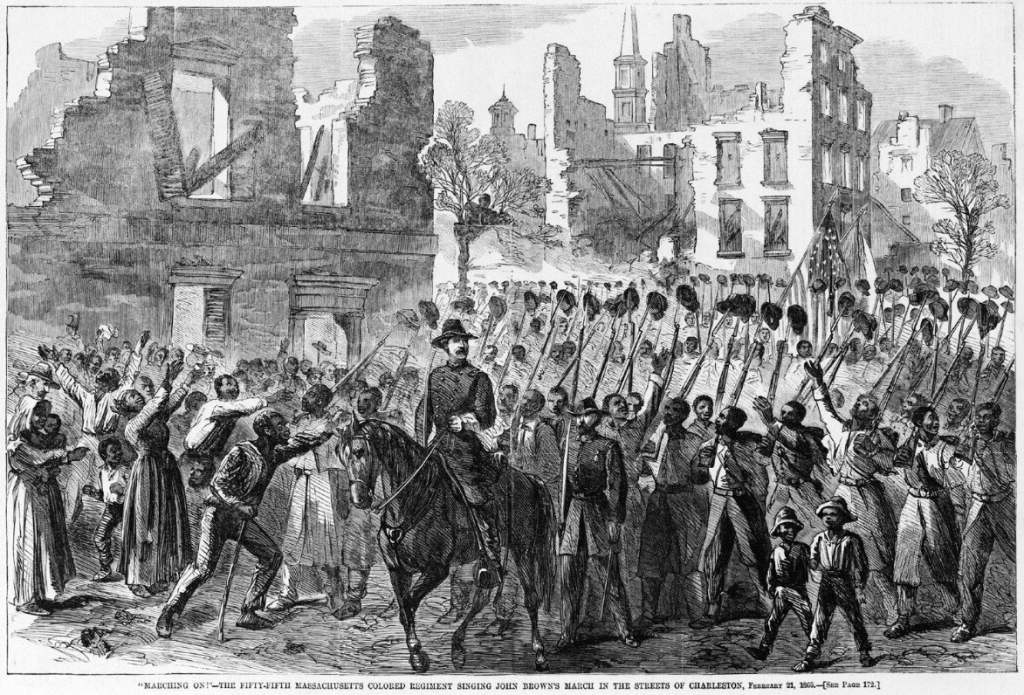

Second, Ludlow was not a pacifist. He believed in just wars waged in the name of freedom, citing the American Revolution and the Union cause during the American Civil War. [12] He supported the draft during WWI and backed the war effort through newspaper articles. [13] Indeed, he even voted with his party, albeit reluctantly, to enter WWII after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. [14] He believed a direct attack justified a declaration of war and included this caveat in his original resolution. What he did not believe in was entering war under the influence of corporations or propaganda. He wanted informed citizens, free of administrative or corporate pressure, to decide for themselves if a cause was worth their lives. He wrote, “I am willing to die for my beloved country but I am not willing to die for greedy selfish interests that want to use me as their pawn.” [15]

So, who was Louis Ludlow and how did he come to advocate for this bold amendment?

“I Must and Would Prove My Hoosier Blood”

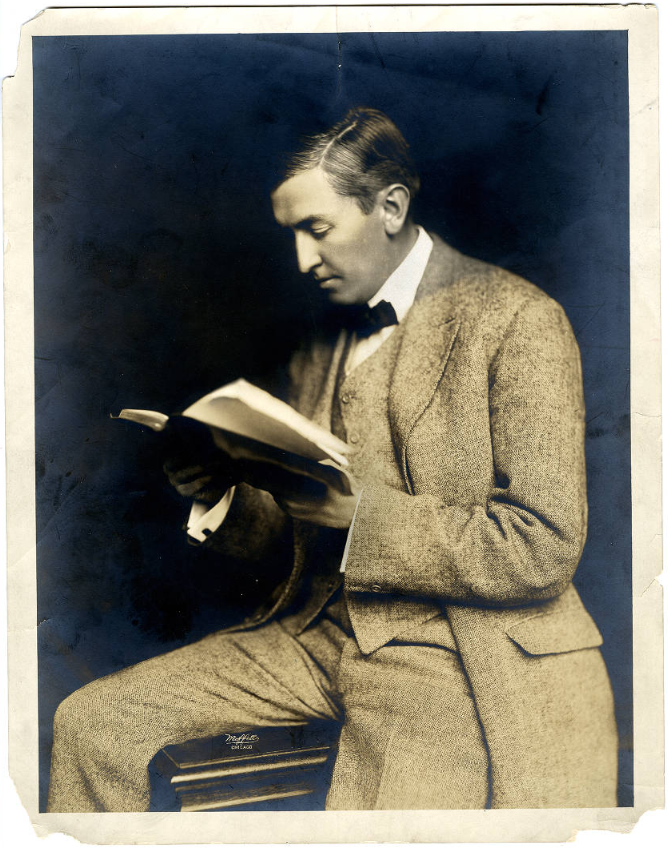

Ludlow described himself as a “Hoosier born and bred” in his 1924 memoir of his early career as a newspaper writer. [16] He was born June 24, 1873 in a log cabin near Connersville, Fayette County, Indiana. His parents encouraged his interests in politics and writing, and after he graduated high school in 1892, he went to Indianapolis “with food prepared by his mother and a strong desire to become a newspaperman.” [17]

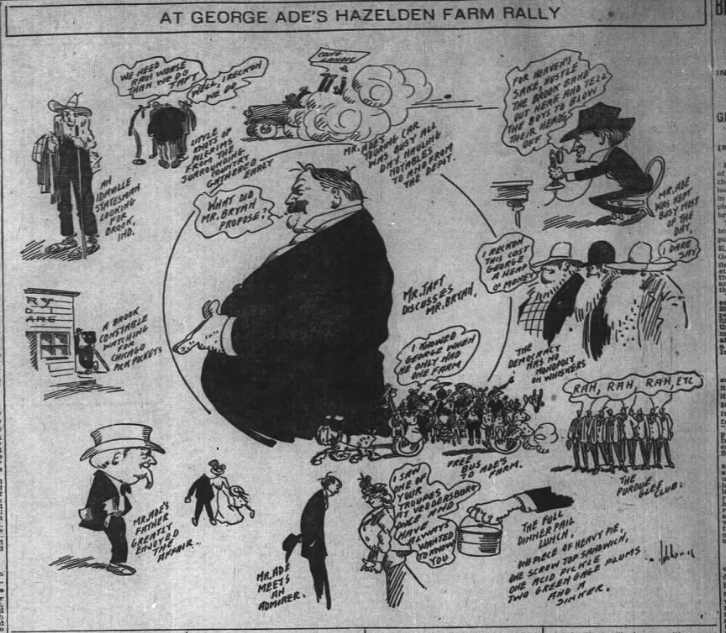

He landed his first job with the Indianapolis Sun upon arrival in the Hoosier capital but quickly realized he needed more formal education. He briefly attended Indiana University before becoming seriously ill and returning to his parents’ home. After he recovered, he spent some time in New York City, but returned to Indianapolis in 1895. He worked for two newspapers, one Democratic (Sentinel) and one Republican (Journal) and the Indianapolis Press from 1899-1901. While he mainly covered political conventions and campaign speeches, he interviewed prominent suffrage worker May Wright Sewall and former President Benjamin Harrison, among other notables. He also became a correspondent for the (New York) World. [18]

In 1901, the Sentinel sent Ludlow to Washington as a correspondent, beginning a twenty-seven-year career of covering the capital. During this time, he worked long hours, expanded his political contacts, and distributed his stories to more and more newspapers. He covered debates in Congress during World War I and was influenced by arguments that membership in the League of Nations would draw the U.S. further into conflict.[19] By 1927 he was elected president of the National Press Club. He was at the height of his journalistic career and had a good rapport and reputation within the U.S. House of Representatives.

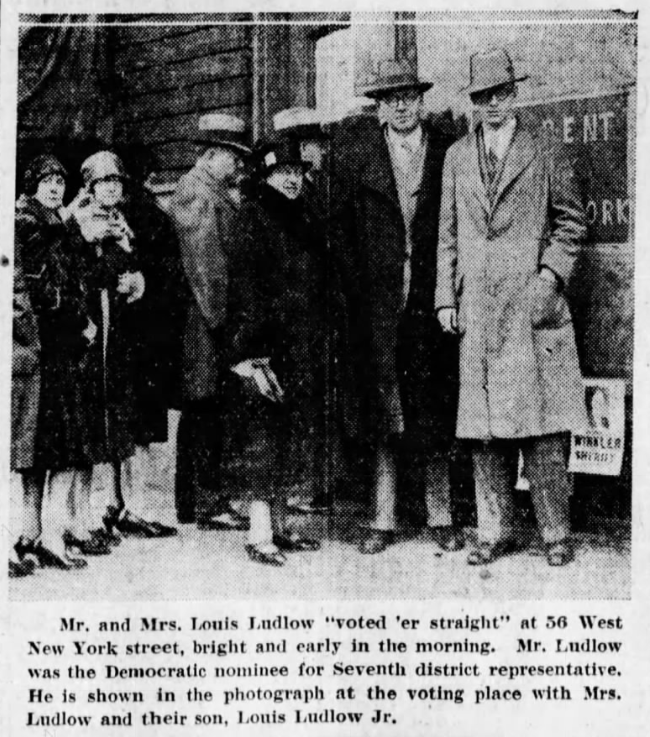

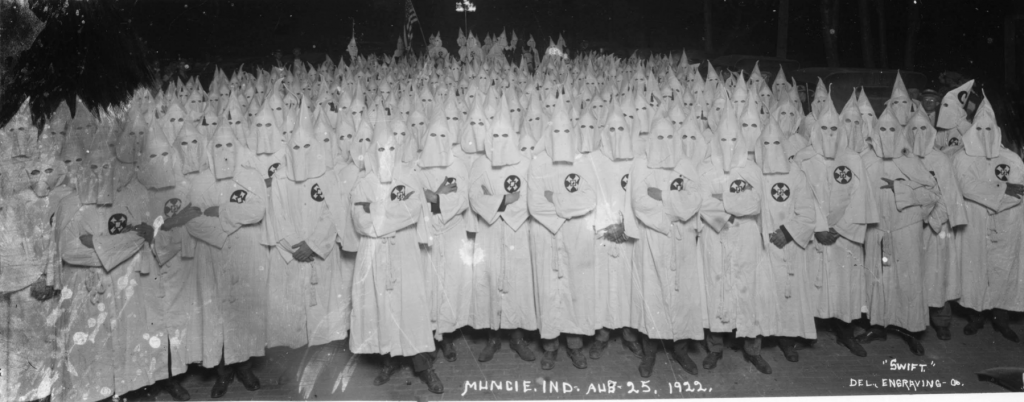

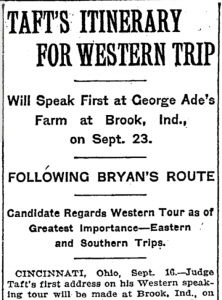

With the backing of Democratic political boss Thomas Taggart, Ludlow began his first congressional campaign at the end of 1927 and announced his candidacy officially on February 23, 1928. [20] The Greencastle Daily Herald quoted part of Ludlow’s announcement speech, noting that the candidate stated, “some homespun honesty in politics is a pressing necessity in Indiana.” [21] He won the Democratic primary in May 1928 and then campaigned against Republican Ralph E. Updike, offering Hoosiers “redemption” from the influence of the KKK. [22] Ludlow “swept to an impressive victory” over Updike in November 1928, as the only Democrat elected from 269 Marion County precincts. [23] He took his seat as the Seventh District U.S. Representative from Indiana on March 4, 1929. [24]

The Indianapolis Star noted that while Ludlow was only a freshman congressman, his many years in Washington as a correspondent had made him “familiar with the workings of the congressional machinery” and “well known to all [House] members,” earning him the “confidence and respect of Republicans and Democrats alike.” [25] The Star claimed: “Perhaps no man ever entering Congress has had the good will of so many members on both sides of the aisle.” [26] This claim was supported by Ludlow’s colleagues on the other side of that aisle. Republican senator James E. Watson of Indiana stated in 1929, “Everybody has a fondness for Louis Ludlow, and as a congressional colleague, he shall have the co-operation of my office in the advancement of whatever he considers in the interest of his constituency.” [27] Republican representative John Cable of Ohio agreed stating:

Louis Ludlow has character and ability. He is the sort of a man who commands the respect and confidence of men and women without regard to party lines. He will have the co-operation of his colleagues of Congress, Republican as well as Democrats, and no doubt will render a high class service for his district.[28]

Cable went so far as to recommend Ludlow for the vice-presidential candidate for the 1932 election.

Ludlow achieved some modest early economic successes for his constituents, including bringing a veterans hospital and an air mail route to Indianapolis. By 1930, however, he set his sights on limiting government bureaucracy and became interested in disarmament as a method to reduce government spending. Concurrently, he threw his support behind the London Naval Treaty which limited the arms race, and he became a member of the Indiana World Peace Committee. During the 1930 election, he stressed his accomplishments and appealed to women, African American, Jews, veterans, businessmen, and labor unions. He was easily reelected by over 30,000 votes. [29]

Back at work in the House, he sponsored an amendment to the Constitution in 1932 to give women “equal rights throughout the United States” which would have addressed legal and financial barriers to equality. He was unsuccessful but undaunted. He introduced an equal rights amendment in 1933, 1936, 1939, 1943, and 1945. [30] [A separate post would be needed to do justice to his work on behalf of women’s rights.] He also worked to make the federal government responsible for investigating lynching, as opposed to the local communities where the injustice occurred. He introduced several bills in 1938 that would have required FBI agents to investigate lynchings as a deterrent to this hate crime, but they were blocked by Southern Democrats. His main focus between 1935 and 1945 was advocating for the passage of legislation to restrict the government’s war powers and end corporate war profiteering.

“To Remove The Profit Incentive to War”

I am convinced from my familiarity with the testimony of the Nye committee and my study of this question that a mere dozen – half a dozen international financiers and half a dozen munitions kings, with a complaisant President in the White House at Washington – could maneuver this country into war at any time, so great are their resources and so far reaching is their power. I pray to God we may never have a President who will lend himself to such activities, but, after all, Presidents are human, and many Presidents have been devoted to the material aggrandizement of our country to the exclusion of spiritual values . . . [31]

Although he admired President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s diplomatic abilities Ludlow thought, as historian Walter R. Griffin asserted, that “it was entirely possible that a future President might very well possess more sordid motives and plan to maneuver the country into war against the wishes of the majority of citizens.” [32] As a protection against the susceptibility of the legislative and especially the executive branches to financial pressures of the munitions industry, Ludlow introduced a simple two-part resolution [HR-167] before the House of Representatives in January 1935. It would amend the Constitution to require a vote of the people before any declaration of war. He summed up the two sections of his bill in a speech before the House in February 1935: “First. To give the people who have to pay the awful costs of war the right to decide whether there shall be war. Second. To remove the profit incentive to war.” [33] He believed that the resolution gave to American citizens “the right to a referendum on war, so that when war is declared it will be the solemn, consecrated act of the people themselves, and not the act of conscienceless, selfish interests using the innocent young manhood of the Nation as its pawns.”[34]

More specifically, Section One stated that unless the U.S. was attacked, Congress could not declare war without a majority vote in a national referendum. And Section Two provided that once war was declared, all properties, factories, supplies, workers, etc. necessary to wage war would be taken over by the government. Those companies would then be reimbursed at a rate not exceeding 4% higher than their previous year’s tax values. [35] This would remove the profit incentive and thus any immoral reasons for a declaration of war.

In an NBC Radio address in March 19235, Ludlow told the public:

The Nye committee has brought out clearly, plainly and so unmistakably that it must hit every thinking persons in the face, the fact that unless we write into the constitution of the United States a provision reserving to the people the right to declare war and taking the profits out of war we shall wake up to find ourselves again plunged into the hell of war . . . [36]

He added that “a declaration of war is the highest act of sovereignty. It is a responsibility of such magnitude that it should rest on the people themselves . . .” [37]

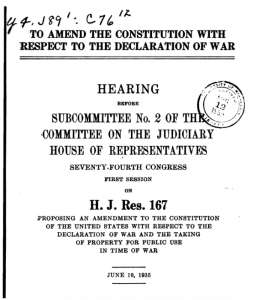

Ludlow’s resolution, soon known as the Ludlow Amendment, was immediately referred to the House Committee on the Judiciary. During committee hearings in June 1935, no one spoke in opposition to the bill and yet the committee did not report on the resolution to the House before the end of the first session in August, nor when they reconvened in 1936. Ludlow attempted to force its consideration with a discharge petition but couldn’t round up enough congressional signatures. Congress was busy creating a second round of New Deal legislation intended to combat the Great Depression and was less concerned with the war clouds gathering over Europe. Despite Ludow’s passionate advocacy both in the House and to the public, his bill languished in committee. In February 1937, he made a fresh attempt, dividing Sections One and Two into separate bills. The same obstacles persisted, and despite gathering more congressional support for his discharge petition, these resolutions too remained in committee. [38]

“What Might Have Been”

During a special session called by Roosevelt in November 1937 (to introduce what has become known as the “court-packing plan”), Ludlow was able to obtain the necessary signatures to release his resolution from committee. While congressional support for the Ludlow Amendment had increased, mainly due to the advocacy of its namesake, opposition had unified as well. Opponents argued that it would reduce the power of the president to the degree that the president would lose the respect of foreign powers and ultimately make the U.S. less safe. Others argued that it completely undermined representative government by circumventing Congress and thus erode U.S. republican democracy. Veterans’ organizations like the American Legion were among its opponents, and National Commander Daniel J. Doherty combined these arguments into a public statement before the January 1939 House vote. He stated that the bill “would seriously impair the functions and utility of our Department of State, the first line of our national defense.” He continued: “The proposed amendment implies lack of confidence on the part of our people in the congressional representatives. This is not in accord with the facts. Other nations would readily interpret it as a sign of weakness.” [39] The Indianapolis Star compared the debates over the resolution to “dynamite” in the House of Representatives. And while Ludlow had the backing of “1,000 nationally known persons,” who issued statements of support, his opponents had the backing of President Roosevelt who continued to expand the powers of the executive branch. In a final vote the Ludlow Amendment was defeated 209-188. [40]

Ludlow continued to be a supporter of Roosevelt and when Japanese forces attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941, the Indiana congressman voted to declare war, albeit reluctantly. He stated:

Japan has determined my vote in the present situation. If the United States had not been attacked I would not vote for a war declaration but we have been attacked . . . American blood has been spilled and American lives have been lost . . . We should do everything that is necessary to defend ourselves and to see that American lives and property are made secure. That is the first duty and obligation of sovereignty. [41]

Looking backward, I cannot escape the belief that the death of the resolution was one of the tragedies of all time. The leadership of the greatest and most powerful nation on earth might have deflected the thinking of the world into peaceful channels. Instead, we went ahead with tremendous pace in the invention of destruction . . . I cannot help thinking what might have been. [43]

Ludlow continued his service as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives until January 1949 after choosing not to seek reelection. Instead of retiring, he returned to the Capitol press gallery where his career had begun some fifty years earlier. And before his death in 1950, he wrote a weekly Washington column for his hometown newspaper, the Indianapolis Star.

“The People . . . Need to Have a Major Voice in the Use of Force . . .”

Ludlow’s eighty-five-year-old argument for giving Americans a greater voice in declaring war gives us food for thought in the current debate over war powers. Today, the conversation has veered away from Ludlow’s call for a direct referendum, but the right of the people’s voices to be heard via their elected representatives is being argued over heatedly in Congress. Many writers for conservative-leaning journals such as the National Review agree with their liberal counterparts at magazines like the New Yorker, that Congress needs to reassert their constitutional right under Article II to declare war and reign in the powers of the executive branch. This, they argue, is especially important in an era where the “enemy” is not as clearly defined as it had been during the World Wars. Writing for the National Review in 2017, Andrew McCarthy argued:

The further removed the use of force is from an identifiable threat to vital American interests, the more imperative it is that Congress weighs in, endorses or withholds authorization for combat operations . . . to ensure that military force is employed only for political ends that are worth fighting for, and that the public will perceive as worth fighting for. [44]

Writing for the New Yorker in 2017, Jeffery Frank agreed, stating:

The constitution is a remarkable document, and few question a President’s power to respond if the nation is attacked. But the founders could not have imagined a world in which one person, whatever his rank or title, would have the authority to order the preemptive use of nuclear weapons – an action that . . . now seems within the realm of possibility. [45]

And in describing the nonpartisan legal group Protect Democracy’s work to create a “roadmap” for balancing congressional and executive powers, conservative writer David French wrote for the National Review that “requiring congressional military authorizations in all but the most emergency of circumstances will grant the public a greater voice in the most consequential decisions any government can make.” [46]

So, if many liberals and conservatives agree that Congress should hold the balance of war powers, who is resisting a return to congressional authorization for military conflicts? According to the Law Library of Congress, the answer would be all modern U.S. Presidents. The library’s website explains that “U.S. Presidents have consistently taken the position that War Powers Resolution is an unconstitutional infringement upon the power of the executive branch” and found ways to circumvent its constraints. [47]

This bloating of executive war power is exactly what Ludlow feared. When his proposed amendment was crushed by the force of the Roosevelt administration, Ludlow held no personal resentment against FDR. He believed that this particular president would always carefully weigh the significance of a cause before risking American lives. Instead, Ludlow’s feared how expanded executive war powers might be used by some future president. In a January 5, 1936 letter, Ludlow wrote:

No stauncher friend of peace ever occupied the executive office than President Roosevelt, but after all, the period of one President’s service is but a second in the life of a nation, and I shudder to think what might happen to our beloved country sometime in the future if a tyrant of Napoleonic stripe should appear in the White House, grab the war power, and run amuck. [48]

A bridge between Ludlow’s argument and contemporary calls for Congress to reassert its authority can be found in the words of more recent Hoosier public servants. Former Democratic U.S. Representative Lee Hamilton and Republican Senator Richard Lugar testified before the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations on April 28, 2009 on “War Powers in the 21st Century.” Senator Lugar stated:

Under our Constitution, decisions about the use of force involve the shared responsibilities of the President and the Congress, and our system works best when the two branches work cooperatively in reaching such decisions. While this is an ideal toward which the President and Congress may strive, it has sometimes proved to be very hard to achieve in practice . . . The War Powers Resolution has not proven to be a panacea, and Presidents have not always consulted formally with the Congress before reaching decisions to introduce U.S. force into hostilities . . . [49]

In 2017, in words that echo Rep. Ludlow’s arguments, Rep. Hamilton reiterated that “the people who have to do the fighting and bear the costs need to have a major voice in the use of force, and the best way to ensure that is with the involvement of Congress.”[50] While the “enemy” may change and while technology further abstracts war, the questions about war powers remain remarkably consistent: Who declares war and does this reflect the will of the people who will fight in those conflicts? By setting aside current political biases and looking to the past, we can sometimes see more clearly into the crux of the issues. Ludlow would likely be surprised that the arguments have changed so little and that we’re still sorting it out.

Further Reading:

Stephen L. Carter, “The Constitutionality of the War Powers Resolution,” Faculty Scholarship Series, January 1, 1984, accessed Yale Law School Legal Scholarship Repository.

Richard F. Grimmet, “War Powers Resolution: Presidential Compliance,” Congressional Research Service Report for Congress, September 25, 2012, accessed Federation of American Scientists.

Walter R. Griffin, “Louis Ludlow and the War Referendum Crusade, 1935-1941” Indiana Magazine of History 64:4 (December 1968), 270-272, accessed Indiana University Scholarworks.

___________________________________________

Footnotes:

[1] The Roosevelts: An Intimate History, A Film by Ken Burns, Premiered September 14, 2014, accessed Public Broadcasting Service.

[2] “Costs of War,” Watson Institute for International & Public Affairs, Brown University; The Editorial Board, “America’s Forever Wars,” New York Times, October 22, 2017. The Times cites the Defense Manpower Data Center, a division of the Office of the Secretary of Defense.

[3] Sarah E. Kreps, “America’s War and the Current Accountability Crisis,” The Diplomat, June 8, 2018.

[4] Ibid.

Kreps writes that this “light footprint warfare,” made possible by technological advancement, creates a “gray zone” in which it’s unclear which actors are responsible for what results, thus fragmenting opposition.

[5] Official Declarations of War by Congress, The United States Senate.

[6] Garance Franke-Tura, “All the Previous Declarations of War,” The Atlantic, August 31, 2013; Robert P. George and Michael Stokes Paulsen, “Authorize Force Now,” National Review, February 26, 2014.

Franke-Tura wrote about congressional use of force in Syria in 2013: “If history is any guide, that’s going to be a rather open-ended commitment, as fuzzy on the back-end as on the front.” Writing for the National Review in 2014, Robert P. George and Michael Stokes Paulsen agreed that in all cases of engaging in armed conflict not in response to direct attack, the president’s power to engage U.S. in military conflict (without an attack on the U.S.) is “sufficiently doubtful” and “dubious.”

[7] “War Powers,” Law Library of Congress; Jim Geraghty, “Is There A War Powers Act on the Books or Not?,” National Review, August 29, 2013.

While the purpose of the War Powers Resolution, or War Powers Act, was to ensure balance between the executive and legislative branches in sending U.S. armed forces into hostile situations, “U.S. Presidents have consistently taken the position that War Powers Resolution is an unconstitutional infringement upon the power of the executive branch” and found ways to circumvent its constraints, according to the Law Library of Congress. Examples include President Reagan’s deployment of Marines to Lebanon starting in 1982, President George H. W. Bush’s building of forces for Operation Desert Shield starting in 1990, and President Clinton’s use of airstrikes and peacekeeping forces in Bosnia and Kosovo in the 1990s.

Writer and National Review editor Jim Geraghty wrote in 2013: “There are those who believe the War Powers Act is unconstitutional – such as all recent presidents . . .” Journals as politically diverse as the National Review and its liberal counterpart the New Yorker, are rife with articles and opinion pieces debating the legality and constitutionality of the Act. Despite their leanings, they are widely consistent in calling on Congress to reassert its constitutional authority to declare war and reign in the war powers of the executive branch.

[8] Ibid.

According to the Law Library of Congress, in 2001, Congress transferred more war power to President George W. Bush through Public Law 107-40, authorizing him to use “all necessary and appropriate force” against nations, groups, or even individuals who aided the September 11 attacks.

[9] Louis Ludlow, Hell or Heaven (Boston: The Stratford Company, 1937).

[10] Walter R. Griffin, “Louis Ludlow and the War Referendum Crusade, 1935-1941,” Indiana Magazine of History 64, no. 4 (December 1968), 270-272, accessed Indiana University Scholarworks. Griffin downplays Ludlow’s early congressional career, however, he pushed for many Progressive Era reforms. Ludlow worked for an equal rights amendment for women, an anti-lynching bill, and the repeal of Prohibition.

[11] Ibid.; United States Congress,“Report of the Special Committee on Investigation of the Munitions Industry (The Nye Report),” Senate, 74th Congress, Second Session, February 24, 1936, 3-13, accessed Mount Holyoke College.

[12] “Speech of Hon. Louis Ludlow of Indiana, in the U.S. House of Representatives,” February 19, 1935, Congressional Record, 74th Congress, First Session, Pamphlets Collection, Indiana State Library.

[13] Ernest C. Bolt, Jr., “Reluctant Belligerent: The Career of Louis Ludlow” in Their Infinite Variety: Essays on Indiana Politicians, eds. Robert Barrows and Shirley S. McCord, (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Bureau, 1981): 363-364.

[14] Griffin, 287.

[15] Louis Ludlow, Public Letter, March 8, 1935, Ludlow War Referendum Scrapbooks, Lilly Library, Indiana University, cited in Griffin, 273.

[16] Louis Ludlow, From Cornfield to Press Gallery: Adventures and Reminiscences of a Veteran Washington Correspondent (Washington D.C., 1924), 1. The section title also comes from this source and page. Ludlow was referring to the Hoosier tendency to write books exhibited during the Golden Age of Indiana Literature.

[17] Ibid., 17; Bolt, 361.

[18] Bolt, 355-359.

[19] Ibid., 360-365.

[20] “Evans Wollen Is Best of the Democrats,” Greencastle Herald, November 7, 1927, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; Charles J. Arnold, “Say!,” Greencastle Herald, February 24, 1928, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Bolt, 371.

[23] “G.O.P. Wins in Marion County,” Greencastle Herald, November 7, 1927, 3, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Ludlow Wins Congress Seat,” Indianapolis Star, November 27, 1928, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[24] Everett C. Watkins, “Ludlow Will Leap from Press Gallery to Floor of Congress,” Indianapolis Star, March 3, 1929, 13, accessed Newspapers.com.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid.

[28] “Republican Advances Ludlow’s Name as 1932 Vice Presidential Candidate,” Indianapolis Star, January 4, 1929, 10, accessed Newspapers.com.

[29] Bolt, 376-377.

[30] “Discuss Women’s Rights,” Nebraska State Journal, March 24, 1932, 3, accessed Newspapers.com; “Women Argue in Favor of Changes in Nation’s Laws,” Jacksonville (Illinois) Daily Journal, March 24, 1932, 5, accessed Newspapers.com; “Woman’s Party Condemns Trial of Virginia Patricide,” Salt Lake Tribune, December 2, 1925, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; “Equal Rights Demanded,” Ada (Oklahoma) Weekly News, January 5, 1939, 7, accessed Newspapers.com; Bolt, 383.

The National League of Women Voters crafted the language of the original bill which Ludlow then sponsored and introduced. In 1935, the organization passed a resolution that “expressed gratitude . . . to Representative Louis Ludlow of Indiana for championing women’s rights.”

[31] “Ludlow Asks War Act Now,” Indianapolis Star, March 13, 1935, 11, accessed Newspapers.com.

[32] Griffin, 281-282.

[33] “Speech of Hon. Louis Ludlow of Indiana, in the U.S. House of Representatives,” February 19, 1935, Congressional Record, 74th Congress, First Session, Pamphlets Collection, Indiana State Library.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid.

[36] “Ludlow Asks War Act Now,” Indianapolis Star, March 13, 1935, 11, accessed Newspapers.com.

[37] Ibid.

[38] “To Amend the Constitution with Respect to the Declaration of War,” Hearing before Subcommittee No. 2 of the Committee on the Judiciary House of Representatives, 74th Congress, First Session, On H. J. Res. 167, accessed HathiTrust; Griffin, 274-275.

[39] Everett C. Watkins, “Ludlow Bill ‘Dynamite’ in House Today,” Indianapolis Star, January 10, 1938, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[40] Griffin, 285.

[41] “Indiana’s Votes Solid for War,” Indianapolis News, December 8, 1941, 4, accessed Newspapers.com.

[42] Congressional Record, 80th Congress, Second Session, Appendix, 4853, in Griffin, 287-8.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Andrew C. McCarthy, “War Powers and the Constitution in Our Body Politic,” National Review, July 8, 2017.

[45] Jeffery Frank, “The War Powers of President Trump,” New Yorker, April 26, 2017.

[46] David French, “Can Congress Get Its War Powers Back?,” National Review, July 5, 2018.

[47] “War Powers,” Law Library of Congress.

[48] Louis Ludlow to William Bigelow, January 5, 1936, in Griffin, 282.

[49] U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, War Powers in the 21st Century, April 28, 2009, Hearing before the Committee on Foreign Relations, United States Senate, 111th Congress, First Session, (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Press, 2010), accessed govinfo.gov.

[50] Bolt, 380-381.

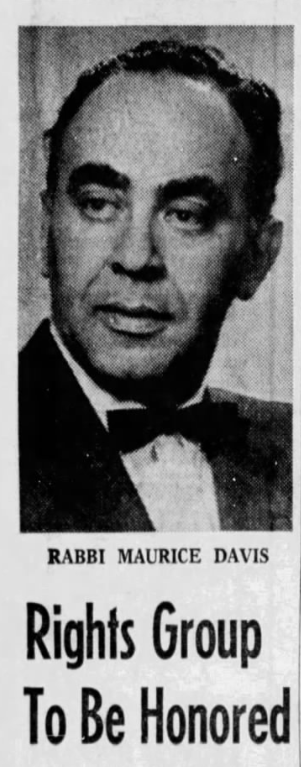

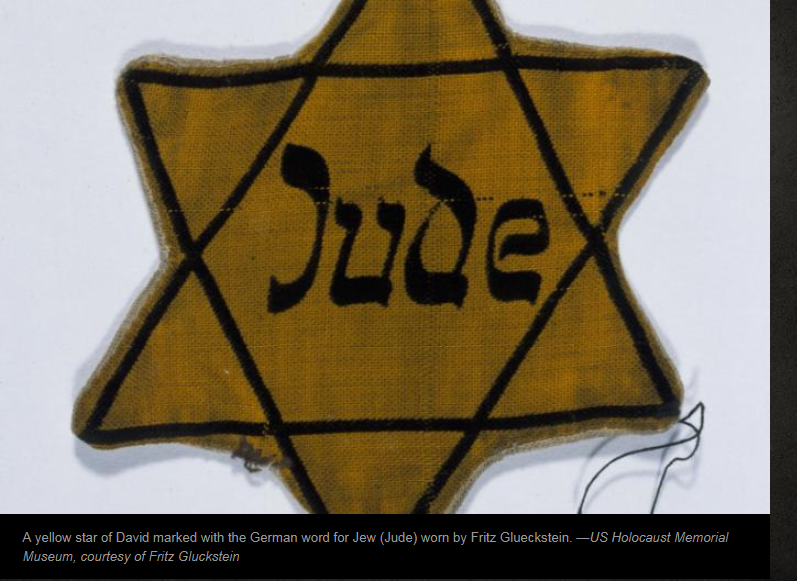

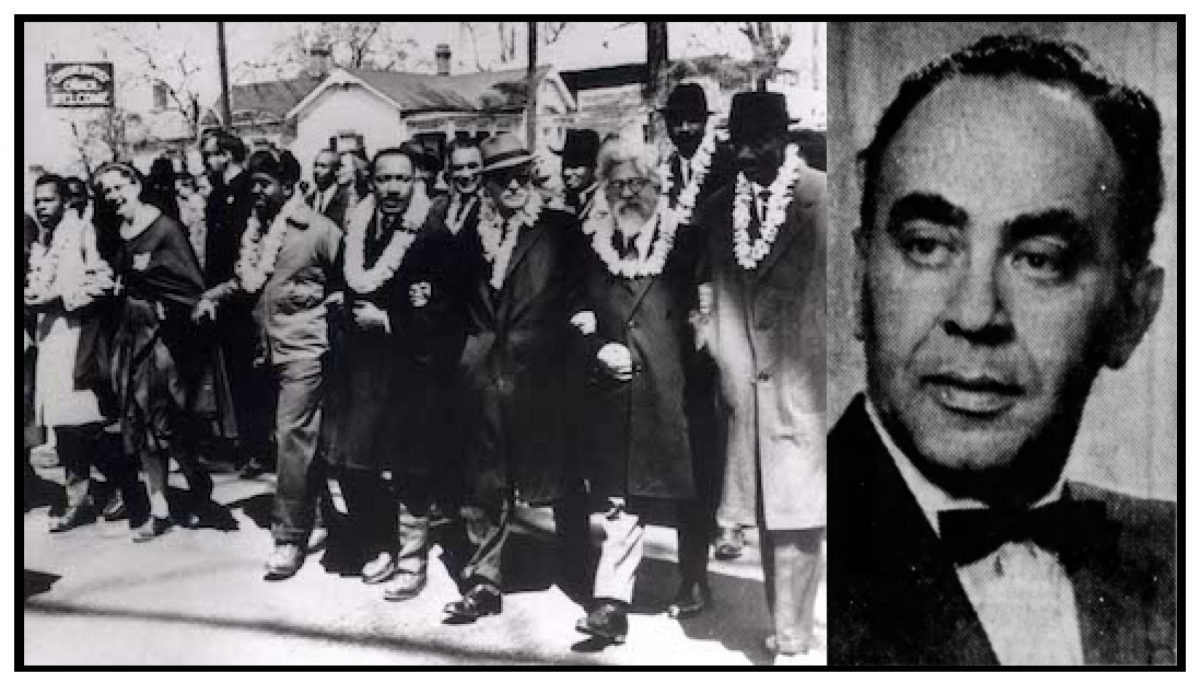

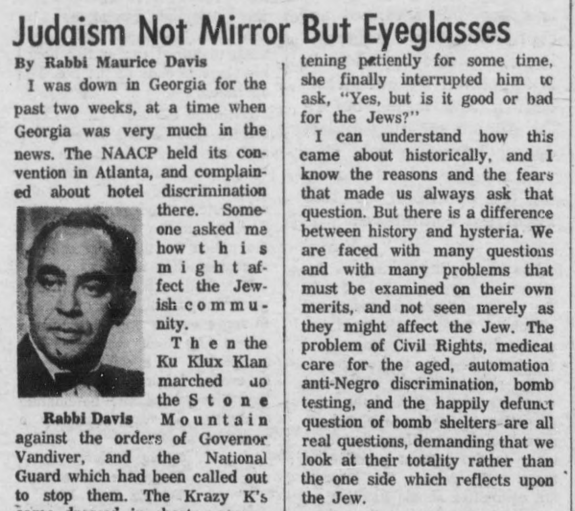

Maurice Davis was born in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1921. Census records show that his Russian-born father Jacob managed a garage while his mother Sadie cared for five children. They did well for themselves and were able to send Maurice first to Brown University in 1939 and then to the University of Cincinnati where he received his B.A. in 1945. He then received his Master of Hebrew Letters from the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. After serving several different congregations as a student rabbi, he became rabbi of Adath Israel in Lexington, Kentucky in 1951. By this point he was already active in the local civil rights movement and joined the Kentucky Commission Against Segregation.

Maurice Davis was born in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1921. Census records show that his Russian-born father Jacob managed a garage while his mother Sadie cared for five children. They did well for themselves and were able to send Maurice first to Brown University in 1939 and then to the University of Cincinnati where he received his B.A. in 1945. He then received his Master of Hebrew Letters from the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. After serving several different congregations as a student rabbi, he became rabbi of Adath Israel in Lexington, Kentucky in 1951. By this point he was already active in the local civil rights movement and joined the Kentucky Commission Against Segregation.

Rabbi Maurice Davis became the spiritual leader of the

Rabbi Maurice Davis became the spiritual leader of the

Rabbi Davis not only advocated for equality for Jews, but all people facing oppression. He encouraged Jews to look beyond their own community and work to end discrimination everywhere. He stated, “A decent and sensitive America is good for all Americans and we must help her be so” (

Rabbi Davis not only advocated for equality for Jews, but all people facing oppression. He encouraged Jews to look beyond their own community and work to end discrimination everywhere. He stated, “A decent and sensitive America is good for all Americans and we must help her be so” (

His columns were often fiery calls to action. For example, in September 1963, he

His columns were often fiery calls to action. For example, in September 1963, he