See Part I to learn about Roberta West Nicholson’s efforts to educate the public about sexual health, her Anti-Heart Balm Bill, and the sexism she faced as the only woman legislator in the 1935-1936 Indiana General Assembly.

Unless otherwise noted, quotations are from Nicholson’s six-part interview with the Indiana State Library.

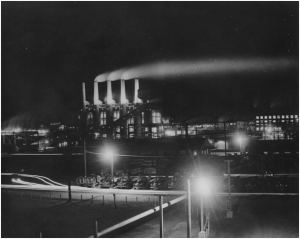

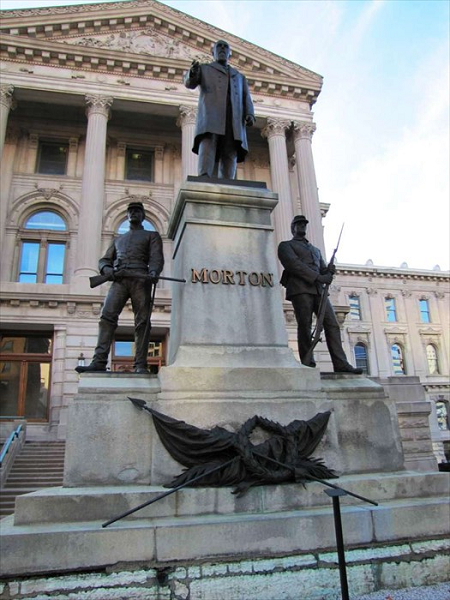

At the conclusion of Nicholson’s term in the Indiana House of Representatives, the country was still in the grip of the Great Depression. Nicholson recalled witnessing a woman standing atop the Governor Oliver P. Morton Statue at the Statehouse to rally Hoosiers from across the state to press Governor Paul McNutt for jobs. She was struck by the fact that the woman was wearing a flour sack as a dress, on which the Acme Evans label was still visible.

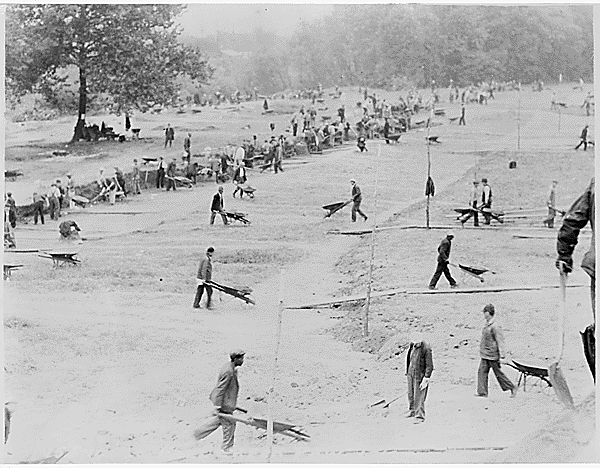

To see for herself if conditions were as dire as she’d heard-despite some local newspapers denying the extent of the poverty-Nicholson took a job at a canning factory. There she learned that the “economic condition was as bad or worse than I had feared.” She hoped to ease this struggle as the Marion County Director of Women’s and Professional Work for the Works Progress Administration (WPA).

As Director, she got further confirmation about the impoverished conditions of Hoosiers during a visit to a transient shelter on Capitol Avenue. She reported:

I couldn’t tell you the dimensions of it, but there were fifteen hundred men on the move that were in this one room and there wasn’t room for them to sit down, much less lie down. They stood all night. They just were in out of the weather. You see, these men were on the move because one of the things about that Depression was that there was lack of real communication, and rumors would go around for blue collar work and they’d say, “They’re hiring in St. Louis,” which proved to be incorrect.

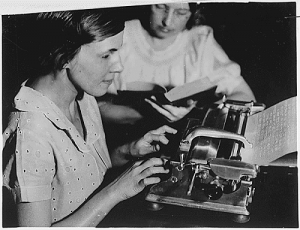

In her role at the Indiana WPA, Nicholson managed all jobs undertaken by women and professionals, which included bookbinding and sewing. She also helped supervise the WPA’s Writer’s Project, consisting of a group of ex-teachers and writers who compiled an Indiana history and traveler’s guide. This project was led by Ross Lockridge Sr., historian and father of famous Raintree County author, Ross Lockridge Jr. Nicholson noted that Lockridge Jr.’s book “had more to do with making me fall in love with my adopted state than anything I can tell you.”

One of Nicholson’s largest tasks involved instructing WPA seamstresses to turn out thousands of garments for victims of the Ohio River Flood in 1937. The workers were headquartered at the State Fair Grounds, where the flood victims were also transported by the Red Cross during the disaster. Nicholson noted that many of the women of the sewing project worked because their husbands had left the family as “hobos,” traveling across the country to look for work; in order to support their families the women made clothes for the “next lower strata of society.”

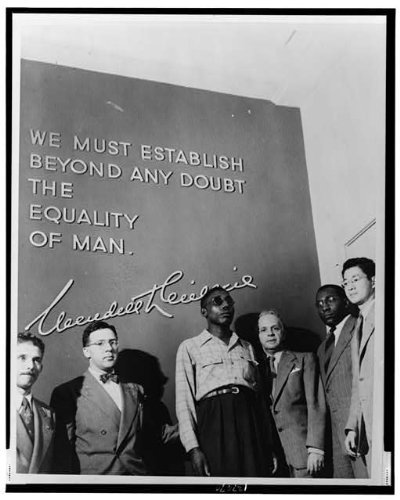

First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt visited their WPA Project, headquartered at the RCA building. The 1500 women continued their work as though nothing were different. Mrs. Roosevelt’s approval seemed to validate the project, especially since the women “were constantly being made fun of for boondoggling and not really doing any work and just drawing down fifty dollars a month.” Nicholson spoke with the First Lady throughout day, concluding “I’ll never forget what a natural, lovely and simple person she was, as I guess all real people are. I was pretty young and it seemed marvelous to me that the president’s wife could be just so easy and talk like anybody else.”

In the early 1940s, Governor Henry F. Schricker appointed Nicholson to a commission on Indianapolis housing conditions. The reformer, who grew up “without a scintilla of prejudice,” concluded that the real estate lobby was at the center of the disenfranchisement of African Americans. As she saw it in 1977, the lobby prevented:

[W]hat we now call ‘upward mobility’ of blacks. I don’t think we would have this school problem in Indianapolis we have now if the emerging class of blacks with education and with decent jobs had not been thwarted in their attempts to live other than in the ghetto. They were thwarted by the real estate laws.

She added that black residents were essentially prohibited to live “anyplace but in the circumscribed areas which the real estate lobby approved . . . And now we have school problems and I think it’s a crying shame that we put the burden for directing past injustices on the backs of little children.”

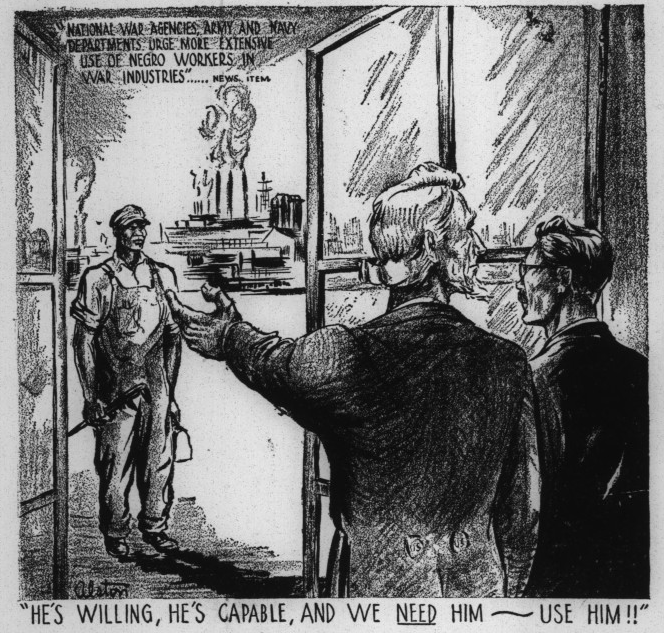

While World War II lifted the country out of the Depression, it magnified discrimination against African Americans. After passage of the Selective Service Act, the City of Indianapolis hoped to provide recreation for servicemen, creating the Indianapolis Servicemen’s Center, on which Nicholson served. She noted that they were able to readily procure facilities for white regiments, such as at the Traction Terminal Building, but locating them for black troops proved a struggle.

Although a black regiment was stationed at Camp Atterbury near Edinburg, Indiana, Nicholson reported that:

The only place to go for any entertainment from Edinburg, Indiana is Indianapolis. Well, what were these black soldiers going to do? They couldn’t go to the hotels, they couldn’t go to any eating place. There was no question of integration at that point. It’s difficult to believe, but this is true; because the Army itself was segregated.

She recalled that her task was so difficult because “There was nowhere near the openness and generosity toward the black soldier that there was toward the white, although they were wearing the same uniform and facing the same kind of dangers.” Lynn W. Turner‘s 1956 “Indiana in World War II-A Progress Report,” reiterated this, describing:

[T]he shameful reluctance of either the USO or the nearby local communities to provide adequate recreational opportunities for Negro troops stationed at Camps Atterbury and Breckenridge and at George and Freeman Air Fields.

Upon this observation, Nicholson fought for black servicemen to be able to utilize the exact same amenities as their white counterparts. One of her tasks included providing troops with a dormitory in the city because “there was no place where these young black men could sleep.” After being turned away by various building owners, Nicholson was allowed to rent a building with “money from bigoted people,” but then came the “job of furnishing it.” With wartime shortages, this proved exceptionally difficult. Nicholson approached the department store L. S. Ayres, demanding bed sheets for the black servicemen. According to Nicholson, some of the Ayres personnel did not understand why the black troops needed sheets if they had blankets. She contended “the white ones had sheets and I didn’t see why the black ones should be denied any of the amenities that the white ones were getting.” Nicholson succeeded in procuring the sheets and a recreation facility at Camp Atterbury for African American soldiers.

Never one to bend to societal, political, or ideological pressure, Nicholson encountered vicious resistance in her support of the Parent Teacher Association (PTA), a national network advocating for the education, safety, and health of children through programming and legislation. She noted that support of the organization was frowned upon in the state because:

[T]hese were the witch-hunting years, you know, and anything that came out of the federal government was bad, and in Indiana that feeling was rife. It was a matter of federal aid education and in Indiana there was a great deal of militant resentment of that federal aid education.

According to Nicholson, a coalition of institutions like the Chamber of Commerce and the Indianapolis Star, along with “some very rich, very ambitious women who wanted to get into the public eye” aligned to destroy the PTA in Indiana. Nicholson recalled that her support of the PTA on one occasion caused a woman to approach her and spit in her face. Ultimately, Nicholson’s opposition won, and defeated the PTA. Nicholson noted that as a result Indiana’s organizations were called “PTOs and they have no connection with the national.” At the time of her ISL interview, she lamented that “without that program for schools where disadvantaged children go, a lot of the schools just simply couldn’t function.”

Nicholson also described a brush with the Red Scare of the 1950s. In a series of articles, an Indianapolis Star journalist accused the State Welfare Department of “being riddled with communism and so forth.” Knowing she was affiliated with one of the women in the department, Governor Schricker summoned Nicholson to his office about the allegations. She noted that while the accused woman was “kinda kooky,” Nicholson was able to assure from “my own knowledge that these two women were possibly off in left field, but that I thought the whole operation was just as clean as anything in the world could be.”

In 1952, desiring respite from the city, the tireless reformer and her husband bought a broken down house in Brown County to fix up for weekend visits. After suffering from ulcers, likely from over-exertion, Nicholson officially retired as the first director of the Indianapolis Social Hygiene Association on December 31, 1960 (serving since 1943). Nicholson passed away in 1987, leaving a positive and enduring imprint on the city’s marginalized population.

Regarding her career, Nicholson combated allegations that she only did what she did because she wanted to be around men. Perhaps an apt summation of her life, Nicholson noted “My way was sort of greased-had a good name and had done some things. I had a reputation for being able to get things done.”