On September 7, 1982, U.S. Representative Adam Benjamin (D-Indiana), a Gary native, was found dead of a heart attack in his Washington, D.C. apartment. Gary Mayor Richard Hatcher, the first African American mayor in the State of Indiana, was tasked with selecting a candidate to run in a special election to complete the last few months of Benjamin’s term. After some intra-party debate, Mayor Hatcher chose Indiana State Senator Katie Hall to serve out the remainder of Benjamin’s term in the U.S. House of Representatives. In November, Hall was elected to Indiana’s first congressional district seat, becoming the first African American to represent Indiana in Congress. When Hall arrived in Washington, D.C., she served as chairwoman of the Subcommittee on Census and Population, which was responsible for holidays. Her leadership in this subcommittee would successfully build on a years-long struggle to create a federal holiday honoring the civil rights legacy of the late Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on his birthday.

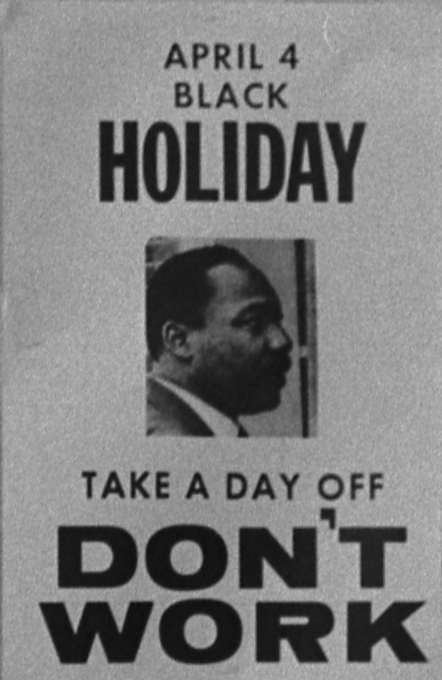

Each year since Dr. King’s assassination in 1968, U.S. Representative John Conyers (D-Michigan) had introduced a bill to make Dr. King’s January 15 birthday a national holiday. Over the years, many became involved in the growing push to commemorate Dr. King with a holiday. Musician Stevie Wonder was one of the most active in support of Conyers’s efforts. He led rallies on the Washington Mall and used his concerts to generate public support. In 1980, Wonder released a song titled “Happy Birthday” in honor of Dr. King’s birthday. The following year, Wonder funded a Washington, D.C. lobbying organization, which, together with The King Center, lobbied for the holiday’s establishment. Coretta Scott King, Dr. King’s widow, ran The King Center and was also heavily involved in pushing for the holiday, testifying multiple times before the Subcommittee on Census and Population. In 1982, Mrs. King and Wonder delivered a petition to the Speaker of the House bearing more than six million signatures in favor of the holiday. For Dr. King’s birthday in 1983, Mrs. King urged a boycott, asking Americans to not spend any money on January 15.

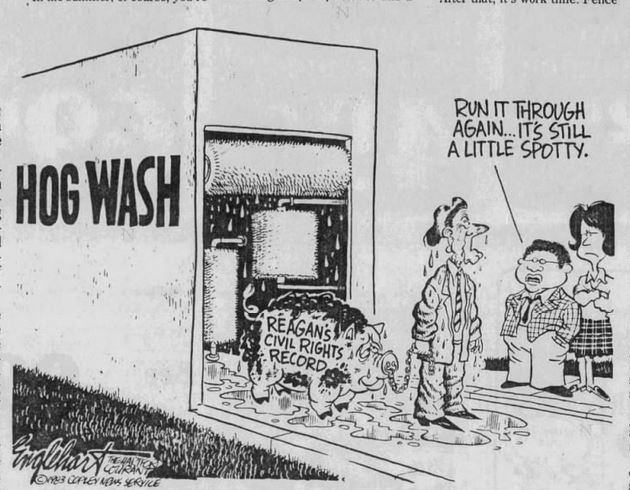

Opponents objected to the proposed holiday for various reasons. North Carolina Republican Senator Jesse Helms led the opposition, citing a high cost to the federal government. He claimed it would cost four to twelve billion dollars; however, the Congressional Budget Office estimated the cost to be eighteen million dollars. Furthermore, a King holiday would bring the number of federal holidays to ten, and detractors thought that to be too many. President Ronald Reagan’s initial opposition to the holiday also centered on concern over the cost; later, his position was that holidays in honor of an individual ought to be reserved for “the Washingtons and Lincolns.”

Earlier in October, Senator Helms had filibustered the holiday bill, but, on October 18, the Senate once again took the bill up for consideration. A distinguished reporter for Time, Neil MacNeil described Helms’s unpopular antics that day. Helms had prepared an inch-thick packet for each senator condemning Dr. King as a “near-communist.” It included:

‘a sampling of the 65,000 documents on [K]ing recently released by the FBI, just about all purporting the FBI’s dark suspicions of commie conspiracy by this ‘scoundrel,’ as one of the FBI’s own referred to King.’

Helms’s claims infuriated Senator Edward Kennedy (D-Massachusetts) because they relied on invoking the memory of Senator Kennedy’s deceased brothers—former President John Kennedy and former U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy—against King. Kennedy was “appalled at [Helms’] attempt to misappropriate the memory” of his brothers and “misuse it as part of this smear campaign.” Senator Bill Bradley (D- New Jersey) joined Kennedy’s rebuttal by calling out Helms’s racism on the floor of the Senate and contending that Helms and others who opposed the King holiday bill “are playing up to Old Jim Crow and all of us know it.” Helms’s dramatic performance in the Senate against the holiday bill had the opposite effect from what he had intended. In fact, Southern senators together ended up voting for the bill in a higher percentage than the Senate overall.

The next day, at an October 19 press conference, Reagan further explained his reluctance to support the bill. Asked if he agreed with Senator Helms’s accusations that Dr. King was a Communist sympathizer, Reagan responded, “We’ll know in about 35 years, won’t we?” His comment referred to a judge’s 1977 order to keep wiretap records of Dr. King sealed. Wiretaps of Dr. King had first been approved twenty years prior by Robert Kennedy when he was U.S. Attorney General. U.S. District Judge John Lewis Smith, Jr. ruled that the records would remain sealed, not until 2018 as Reagan mistakenly claimed, but until 2027 for a total of fifty years. However, President Reagan acknowledged in a private letter to former New Hampshire Governor Meldrim Thomson in early October that he retained reservations about King’s alleged Communist ties, and wrote that regarding King, “the perception of too many people is based on an image, not reality.”

Support was gaining ground around the country; by 1983 eighteen states had enacted some form of holiday in honor of Dr. King. Politicians could see the tide of public support turning in favor of the holiday, and their positions on the holiday became something of a litmus test for a politician’s support of civil rights.

After Helms’s acrimonious presentation in late October, Mrs. King gave an interview, published in the Alexandria, Louisiana Town Talk, saying that it was obvious since Reagan’s election that:

‘he has systematically ignored the concerns of black people . . . These conservatives try to dress up what they’re doing [by attempting to block the King holiday bill] . . . They are against equal rights for black people. The motivation behind this is certainly strongly racial.’

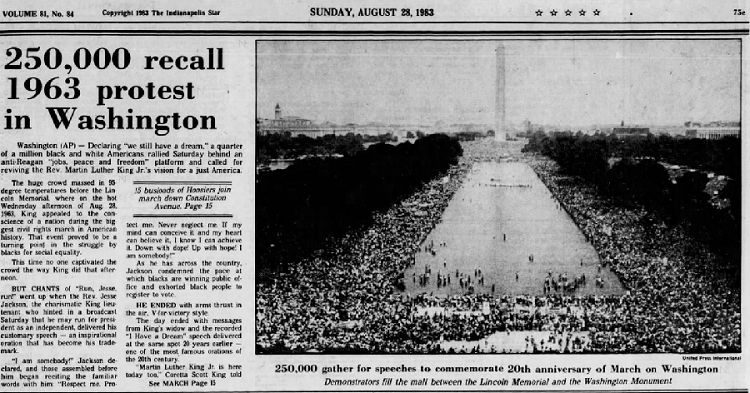

Town Talk noted that “Mrs. King said she suspects Helms’s actions prompted a number of opposed senators to vote for the bill for fear of being allied with him.” Some editorials and letters-to-the-editor alleged that Reagan ultimately supported and signed the King holiday bill to secure African American votes in his 1984 reelection campaign. In August 1983, Mrs. King had helped organize a rally at the National Mall in Washington, D.C. in celebration of the twentieth anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington, at which King gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. Between 250,000 and 500,000 Americans attended; all speakers called on Reagan to sign the MLKJ Day bill.

Hall was busy building support among her colleagues for the holiday; she spent the summer of 1983 on the phone with legislators to whip votes. As chair of the House Subcommittee on Census and Population, Hall led several hearings called to measure Americans’ support of a holiday in memory of King’s legacy. According to the Indianapolis Recorder, “among those who testified in favor of the holiday were House Speaker Thomas ‘Tip’ O’Neill, Rep. John Conyers Jr. (D-Mich.), Sen. Edward Kennedy (D.-Mass.), singer Stevie Wonder and Coretta Scott King.” Additionally, a change in the bill potentially helped its chances by addressing a key concern of its opponents—the cost of opening government offices twice in one week. At some point between when Conyers introduced the bill in January 1981 and when Hall introduced the bill in the summer of 1983, the bill text was changed to propose that the holiday be celebrated every third Monday in January, rather than on King’s birth date of January 15.

After the House passed the bill on August 2, Hall was quoted in the Indianapolis News with an insight about her motivation:

‘The time is before us to show what we believe— that justice and equality must continue to prevail, not only as individuals, but as the greatest nation in this world.’

For Hall, the King holiday bill was about affirming America’s commitment to King’s mission of civil rights. It would be another two and a half months of political debate before the Senate passed the bill.

The new holiday was slated to be officially celebrated for the first time in 1986. However, Hall and other invested parties wanted to ensure that the country’s first federal Martin Luther King Jr. Day would be suitably celebrated. To that end, Hall introduced legislation in 1984 to establish a commission that would “work to encourage appropriate ceremonies and activities.” The legislation passed, but Hall lost her reelection campaign that year and was unable to fully participate on the committee. Regardless, in part because of Hall’s initiative, that first observance in 1986 was successful.

In Hall’s district, Gary held a celebration called “The Dream that Lives” at the Genesis Convention Center. Some state capitals, including Indianapolis, held commemorative marches and rallies. Officials unveiled a new statue of Dr. King in Birmingham, Alabama, where the leader was arrested in 1963 for marching in protest against the treatment of African Americans. In Washington, D.C., Wonder led a reception at the Kennedy Center with other musicians. Reverend Jesse Jackson spoke to congregants in Atlanta where Dr. King was minister, and then led a vigil at Dr. King’s grave. Mrs. King led a reception at the Martin Luther King, Jr., Center, also in Atlanta.

Representative Hall knew the value of the Civil Rights Movement first hand. Born in Mississippi in 1938, Hall was barred from voting under Jim Crow laws. She moved her family to Gary, Indiana in 1960, seeking better opportunities. Her first vote ever cast was for John F. Kennedy during the presidential race that year. Hall was trained as a school teacher at Indiana University and she taught social studies in Gary public schools. As a politically engaged citizen, Hall campaigned to elect Mayor Hatcher and ran a successful campaign herself when in 1974 she won a seat in the Indiana House of Representatives. Two years later, she ran for Indiana Senate and won. Hall and Julia Carson, elected at the same time, were the first Black women elected to the state senate. While in the Indiana General Assembly, Hall supported education measures, healthcare reform, labor interests, and protections for women, such as sponsoring a measure to “fund emergency hospital treatment for rape victims,” including those who could not afford to pay.

Hall was still serving as Indiana state senator in 1982 when Representative Benjamin passed away and Mayor Hatcher nominated her to complete Benjamin’s term. She made history in November 1982, when in the same election she won the campaign to complete Benjamin’s term, as well as being elected to her own two year term, becoming the first African American to represent Indiana in Congress. However, Hall lost her bid for reelection during the 1984 primaries to Peter Visclosky, a former aide of Rep. Benjamin who still holds the seat today. Hall ran for Congress again in 1986, this time with the endorsement of Mrs. King. Although she failed to regain the congressional seat, Hall remained active in politics. In 1987, Hall was elected Gary city clerk, a position she held until 2003 when she resigned amid scandal after an indictment on mail fraud, extortion, and racketeering charges. In June 1989, Dr. King’s son Martin King III wrote to Hall supporting her consideration of running again for Congress.

Hall passed away in Gary in 2012. The establishment of the federal Martin Luther King, Jr. holiday law was Hall’s crowning achievement. Her success built upon a fifteen-year-long struggle to establish a national holiday in honor of Dr. King. The Indiana General Assembly passed a state law in mid-1989 establishing the Dr. King holiday for state workers, but it was not until 2000 that all fifty states instituted a holiday in memory of Dr. King for state employees.

The Martin Luther King, Jr. holiday has endured despite the struggle to create it. In 1994, President Bill Clinton signed a bill sponsored by Senator Harris Wofford (D-Pennsylvania) and Representative John Lewis (D-Georgia) that established Martin Luther King Day as a day of service, encouraging wide participation in volunteer activities. Inspired by King’s words that “everyone can be great because everyone can serve,” the change was envisioned as a way to honor King’s legacy with service to others. Today, Martin Luther King Day is celebrated across the country and politicians’ 1983 votes on it continue to serve as a civil rights litmus test.

Mark your calendars for the April 2019 dedication ceremony of a state historical marker in Gary commemorating Representative Hall and the origins of Martin Luther King, Jr. Day.

Click here for a bibliography of sources used in this post and the forthcoming historical marker.