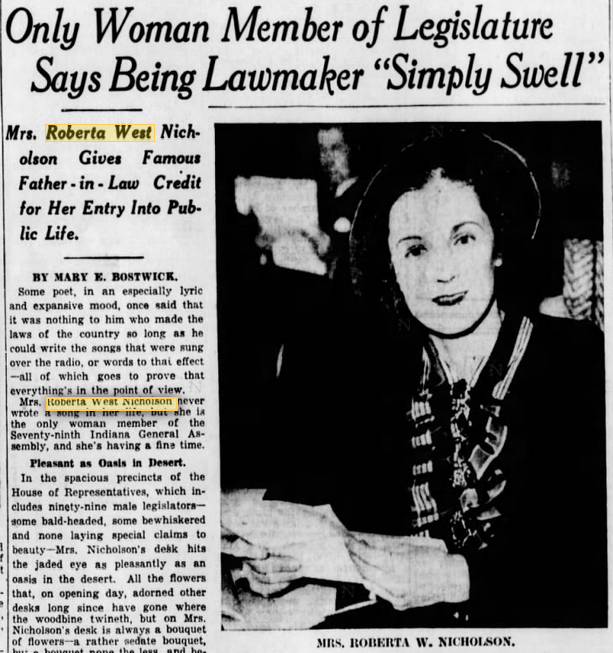

If Roberta West Nicholson has received any recognition at all, it’s been from Men’s Rights Groups, who have praised her revolutionary Anti-Heart Balm Bill. However, the bill, like much of her work, was progressively liberal and centered around equality. As the only woman legislator in 1935-1936, in her work to educate the public about sexual health, efforts against discrimination in Indianapolis, and champion children’s causes, West was a public servant in the purest sense. Despite her tireless work, she struggled to escape the shadow of her father-in-law, famous Hoosier author Meredith Nicholson, and to be associated with social reform rather than her “cuteness.” In an interview with the Indiana State Library (ISL) conducted in the 1970s, she did just that, but unfortunately, it has been largely overlooked.

Even as a young college student, the Cincinnati, Ohio native deviated from the norm. Nicholson attended one semester at the University of Cincinnati, leaving after an exasperating experience with the sorority system, which she found “excessively boring.” Unbending to sorority policies which required dating male pledges and attending numerous parties, it became evident that Nicholson interests were incompatible with those of her sisters. After one of several instances of bullying, she proudly returned the sorority pin, withdrew from the college, and went to finishing school.

Roberta met her husband, Meredith Nicholson Jr., at a summer resort in Northport Point, MI. In 1925, the two were married and she moved to Indiana, where she was “absolutely bowled over by the fact that it was virtually the headquarters of the Ku Klux Klan and their vile machinations.” From a politically conservative family, Mrs. Nicholson soon found that in Indiana “the Republican party, as far as I could ascertain, was almost synonymous with the Ku Klux Klan. Well, how could you be anything but a Democrat, you know? That was to be on the side of angels so to speak.”

The day of her wedding, Roberta’s father received two letters, “terrible penmanship-pencil on cheap lined paper-warning him to stop the marriage of his daughter to that ‘nigger loving Jew.'”* Her father spent a large amount of money trying to identify the author of the “vitriolic hatred,” an attempt that proved unsuccessful. The couple’s wedded bliss was also impeded by the Great Depression, in which Meredith Jr. lost everything in the stock market and “this beautiful dream world we’d been living in is all of a sudden gone.” Following the bankruptcy of her husband’s company, Roberta took a job at Stewarts book store, supporting the family on $15 a week.

After the adoption of liberal principles, Nicholson engaged in her first real reform work in 1931. Birth control activist Margaret Sanger reportedly solicited Nicholson to help establish Indianapolis’s first Planned Parenthood center. A New York representative visited Nicholson in the city, describing the “very, very disappointing lack of progress they seemed to be making because there was apparently very little known about family planning and very little support in general terms for such a concept.” Nicholson was convinced that this should change and established a chapter in Indianapolis. Thus began Nicholson’s 18 years-long work as a family planning and social hygiene advocate.

Outside of her role in Planned Parenthood, she worked as a public educator, going into cities, sometimes “very poor, miserable ghetto neighborhood[s],” to increase awareness of the “menace of venereal disease.” It became clear to Nicholson that ignorance about sexual health was widespread, including her own lack of knowledge about diseases, which she had referred to syphilis as the “awful awfuls” and gonorrhea the “never nevers.” During these often uncomfortable meetings with the public, Nicholson sought to inspire an open dialogue and a back and forth about taboo subjects. Nicholson also showed reproduction films to middle schoolers a job that provoked titters by students and sometimes outrage on the part of parents.

Her dedication to improve the welfare of children intensified during the Great Depression, when she witnessed impoverished children modeling clothes made by WPA employees. This was an effort to prove to those Indianapolis newspapers highly critical of Roosevelt’s New Deal that social programs were effective. Seeing these children being used to “get some bigoted publisher to change his views on some very necessary emergency measures” made her think of her own children and brought her to tears. In her ISL interview, she stated that “I decided that I was going to spend the rest of my life helping children that were disadvantaged, and I have.”

In 1932, Nicholson founded the Juvenile Court Bi-Partisan Committee, to convince politicians to reform juvenile justice and “keep the court out of politics and to employ qualified persons to handle the children.” These efforts proved successful, when in 1938 Judge Wilfred Bradshaw reformed the court. Nicholson served as a longtime committee member and in 1946, when other members became frustrated with progress and resigned, Nicholson stayed, saying “I feel that because you are going to sometimes lose your point of conviction doesn’t mean you throw the baby out with the bathwater.” Nicholson also worked to improve the lives of Indianapolis children as the president of the Children’s Bureau, an adoption agency and group home, and in her work on the board of Directors of the Child Welfare League.

At the encouragement of her mother-in-law, she worked with the Women’s Organization for National Prohibition Repeal. In her interview with ISL, she explained her motive for joining the effort to repeal the 18th Amendment:

“These women felt very deeply about the fact that prohibition had inaugurated the era of of the gangsters: the illicit traffic in liquor, with no taxes and everything. They were building this empire of crime…And I said, ‘I am interested in it because these are the craziest days.’ Everybody had a bootlegger. I suppose real poor people didn’t but you never went to a party where there weren’t cocktails. I remember feeling very deeply ashamed to think that my children would be growing up with parents who were breaking the law. How was I going to teach them to fly right? I certainly wasn’t up to bucking the trend. So I thought, ‘All right, Ill work on this, that’s fine.’”

In 1933, Governor Paul V. McNutt appointed her to the Liquor Control Advisory Board and she was elected secretary to the state constitutional convention that ratified the 21st Amendment, repealing prohibition.

Her experience and qualifications made her a natural choice for public office. In 1934, she was convinced by the county chairman to run for Legislature during the FDR administration because “the Democrats smelled victory, because of the dramatic actions of the president. They wanted to get some names they thought would be meaningful to the voters so they invited me.” Although Nicholson had studied the issues in depth, it turned out that in order to be elected “all that was expected of one was to step up to the podium and say, ‘I stand four square behind FDR.’ That did it.”

Win she did, becoming the only woman to serve in the 1935-1936 legislature, where she faced sexism. According to the Indianapolis Star, during her time as secretary of the public morals committee, she informed her committeemen, “‘If you think you’re going to stop me from talking just because I’ll be taking minutes, you’re wrong-I’ve got some things to say, and I’m going to say them.'” Nicholson elaborated that many of her colleagues thought:

“Wasn’t it cute of her. She’s got a bill. She’s going to introduce it just like a man. Isn’t that darling?’ I restrained myself, because after all I was in the distinct minority. I could not offend them. So I would just bat my eyelashes and beam at them and act as if I thought it was the way I wanted to be treated. Wasn’t that the only thing to do?”

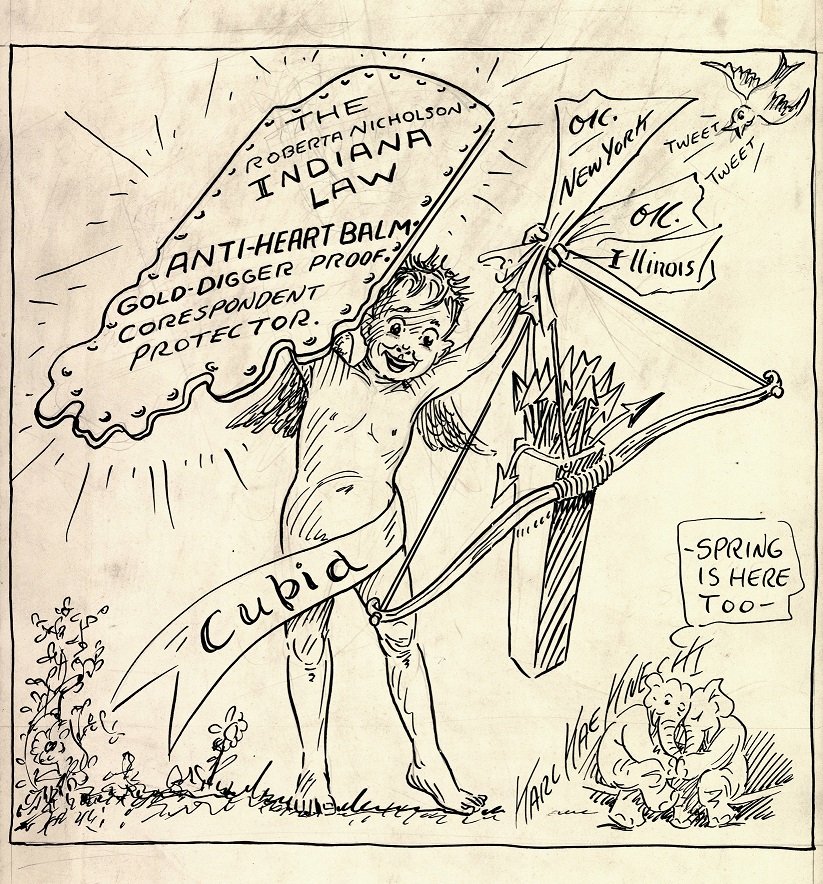

Not only did she “have” a bill, but her breach of promise bill, dubbed the “Anti-Heart Balm Bill,” made waves in Indiana and across the country. Nicholson’s proposal would outlaw the ability of a woman to sue a man who had promised to marry them, but changed their minds. She felt that deriving monetary gain from emotional pain went against feminist principles and that if a man did the same to a woman he would be absolutely condemned. Nicholson described her reasoning for the bill, which generally had the support of women across the nation:

“…it just seemed perfectly silly to me, that from time immemorial, a female being engaged to be married could change her mind and say, ‘Sorry Joe, it’s all off.’ But if the man did, and if he had any money, he could be sued. I thought that was absolutely absurd. . . . The thing that was so amazing and truly surprising to me is that it was widely interpreted as giving free reign to predatory males to take advantage of chaste maidens which, of course, was diametrically opposed to what my conception was. I thought-and I still think-that it was an early blow for women’s liberation. I thought it was undignified and disgusting that women sued men for the same changing their mind about getting married.”

Nicholson’s bill passed the House fairly easily, but was held up in the Senate because, in her opinion, “Something new was being tried and several of the senators felt, ‘Why should we be first?” The bill also encountered resistance by lawyers who profited from breach of promise suits. Eventually the bill passed, inspiring similar legislation in other states. The Indianapolis Star credited Nicholson’s bill with bringing the “Spotlight, Pathe News, Time and Look magazines hurrying to Indiana by sponsoring and successfully promoting the famous heart-balm bill which has saved many a wealthy Indianian embarrassment, both social and financial by preventing breach of promise suits.”

After passage of the “Gold-Diggers bill,” Nicholson was invited to speak around the country. At an address to the Chicago Association of Commerce and the Alliance of Business and Professional Women, she said “It seemed to me that we should say to these gold diggers and shyster lawyers, as did the Queen in ‘Alice in Wonderland,’ ‘Off with their heads!” She added, “I am not a professional moralist, but I have attempted to set up a deterrent to irregular relations by removing the prospect of pecuniary profit from them.”

Nicholson also received criticism during her legislative career for supporting the Social Security Act, for which a special session was called in 1936. The Head of the Indiana Taxpayers Association stopped her near the statehouse and asked if she would be voting for “‘that terrible communist social security.'” When she confirmed she was, Nicholson noted that his face creased with rage and he sped off in his chauffeured car. A state senator shared his conviction, contending that the act’s supporters were “‘Trying to turn this country into a GD Ethiopia!'”

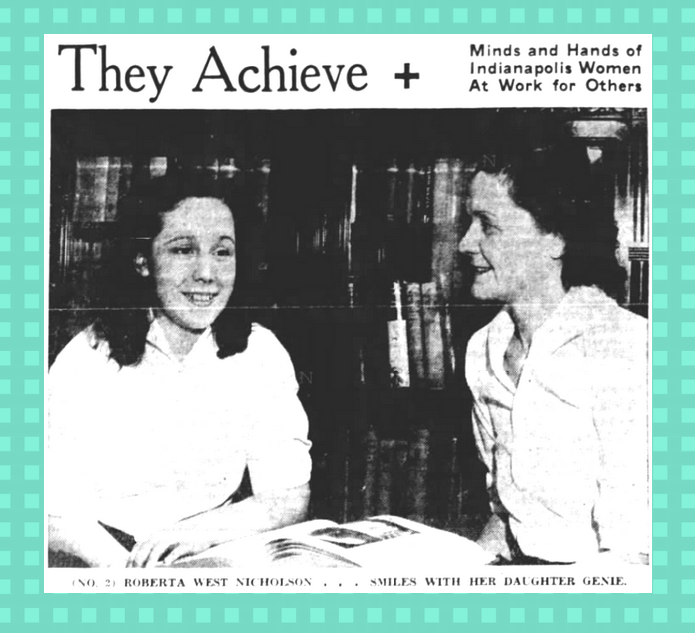

Perhaps the most intense scrutiny Nicholson faced as a lawmaker was in her role as a working mother. The Indianapolis Star noted that nothing made Nicholson madder than “to have interfering friends charge that she is neglecting her family to pursue the career of a budding stateswoman.” The paper relayed Nicholson’s response:

“‘Some of my friends have told me that they think it is ‘perfectly terrible’ of me to get myself elected to the Legislature and spend the greater part of sixty days away from the children. . . . I told them, ‘I don’t spend any more time away from my children than other mothers do who play bridge and go to luncheons all the time.’ I try to be a good mother and so far as my being in the Legislature preventing me from going to parties is concerned, I don’t care much for parties anyway!'”

Despite criticism, Nicholson proved steadfast in her political convictions and was perceived of as a “force” by many observers; the Indianapolis Star proclaimed “Mrs. Nicholson yesterday wore a modish dark red velvet dress and smoked cigarettes frequently during the proceedings, and if any of her fellow legislators didn’t like it, it was just too bad. It was a pleasure to watch her.” When her term ended, the tenacious legislator ran for reelection, but lost because the political climate swung in favor of the Republican Party. However, this was far from the end of her public service.

Check back for Part II to learn about her WPA work alongside Ross Lockridge Sr.; visit with Eleanor Roosevelt; tiresome efforts to find housing for African American soldiers in Indianapolis who had been turned away; and observations about the Red Scare in local politics.

*The Nicholsons were not Jewish. It is likely that the author of the letter used the word “Jew” as a derogatory term for progressives.

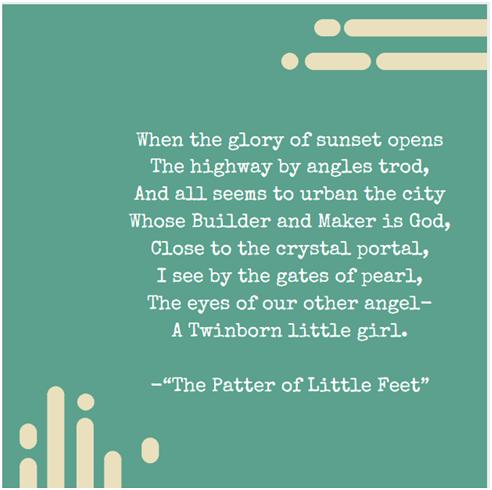

The poem goes on to describe the mother’s longing that she will someday reach heaven and hear the patter of her daughter’s feet on heaven’s floor.

The poem goes on to describe the mother’s longing that she will someday reach heaven and hear the patter of her daughter’s feet on heaven’s floor.

Interestingly, this poem does not seem to have raised any speculation regarding Lew’s faithfulness to Susan.

Interestingly, this poem does not seem to have raised any speculation regarding Lew’s faithfulness to Susan.