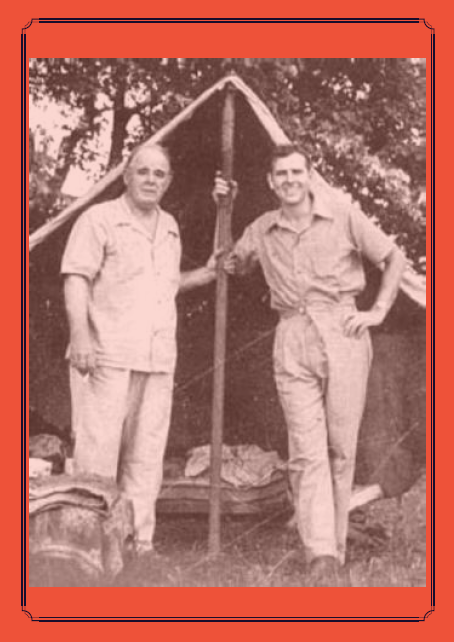

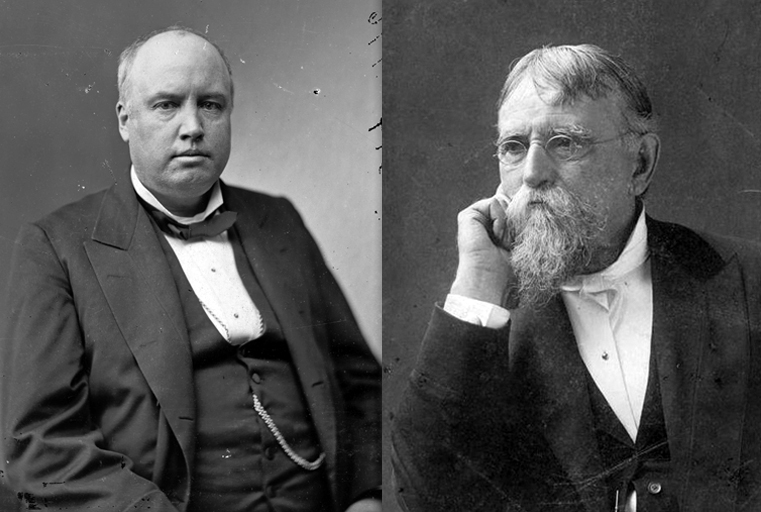

Ross Lockridge Sr. and Jr. left an indelible mark on Indiana history through traditional history publications and fictional depiction. However, the father and son have yet to be cemented in the annals of state history. We hope to contribute to that reversal.

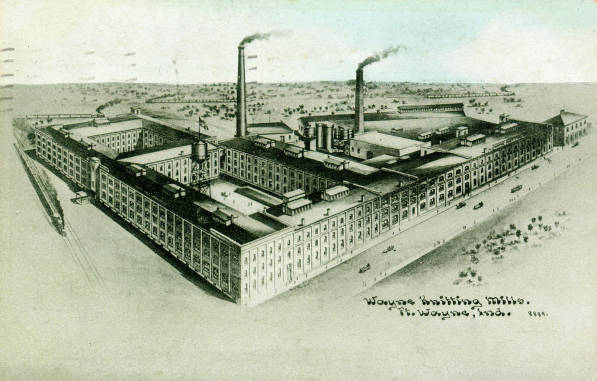

The senior Lockridge was born in Miami County, Indiana in 1877 and went on to graduate from Indiana University in 1900. He married and returned to his north central Hoosier home. He became the principal of Peru High School, and later earned a law degree from IU in 1907. Not long after, he moved to Fort Wayne and worked as employment manager and welfare director at Wayne Knitting Mills. He also served three years as executive secretary of the Citizen League of Indiana, which lobbied for a new state constitution and advocated for women’s suffrage.

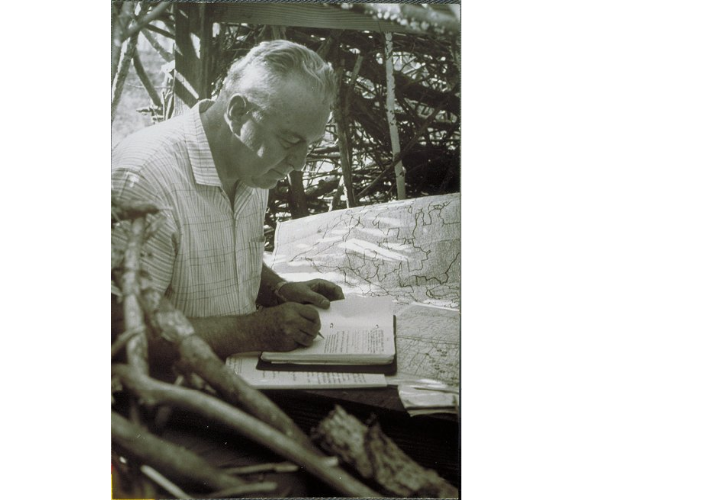

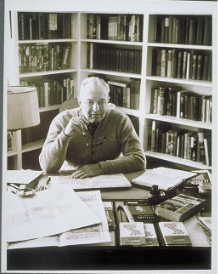

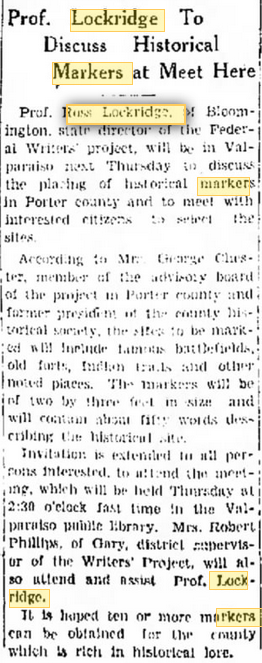

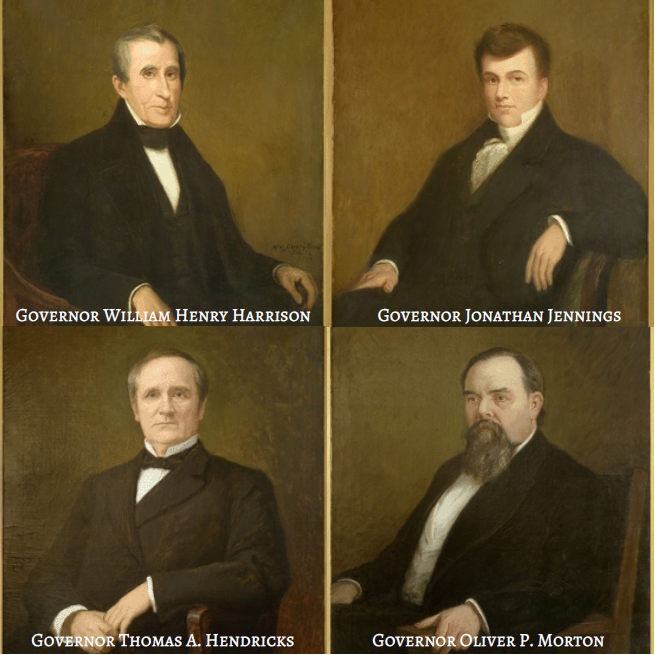

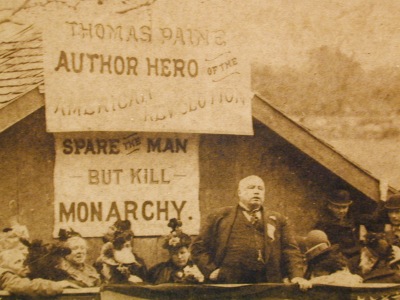

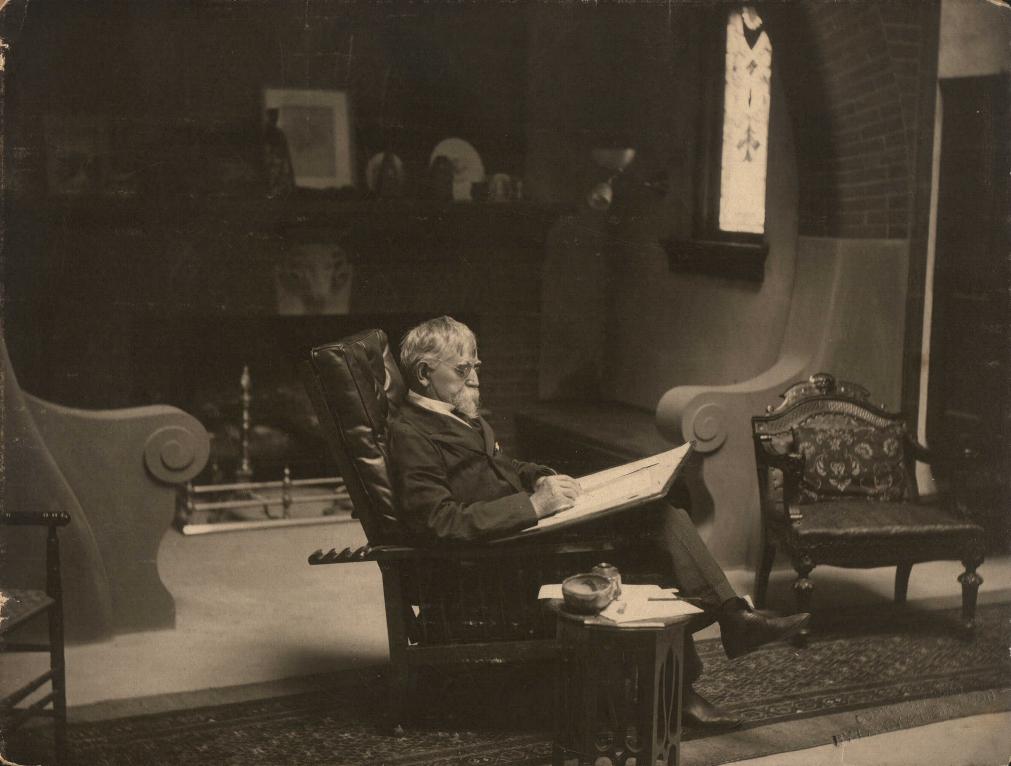

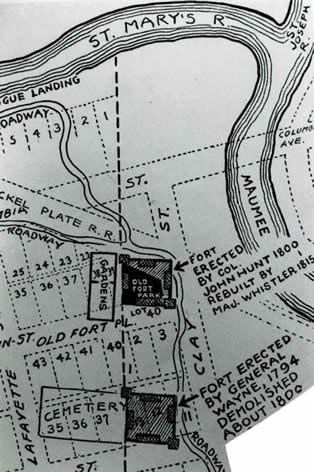

While in Fort Wayne, Lockridge Sr. helped organize the Allen County Fort Wayne Historical Society. During this time his reputation grew as a writer of pioneer Indiana history. According to Larry Lockridge, his grandfather, Ross Sr.,” developed his own brand of ‘Historic Site Recital,’ combing public speaking, drama, and local history.” Between 1937 and 1950, Lockridge Sr. served as a director of IU Foundation’s Hoosier Historic Memorial Activities Agency. Some of his published works include: George Rogers Clark (1927), A. Lincoln (1930), LaSalle (1931), The Old Fauntleroy Home (1939), and Labyrinth (1941), Theodore F. Thieme (1942). His The Story of Indiana (1951) was primarily used as a text in Indiana at the junior high school level.

The historian also wrote about Johnny Appleseed, the Underground Railroad, and Indiana’s trails, rivers, and canals. Another extended work, which continues to aid transportation history researchers, is Historic Hoosier Roadside Sites, commissioned in 1938 by the Indiana State Highway Association. He worked tirelessly to mark the state’s landscape with monuments and markers, preserve records, and execute historical pageants. His clear and concise writing style has added to Hoosier’s knowledge of their past.

According to Larry Lockridge, his grandfather “didn’t exactly whitewash history,” but he “certainly edited it. He attempted to bind people to their own local history through heroic narrative.” After the tragic drowning of Ross Sr.’s 5-year-old son, Bruce, in Fort Wayne, his dedication to historical work intensified. Larry contends:

“Preaching history as resurrection of the worthy dead was his idealistic, nonmetaphysical challenge to time and mortality, grounded in the tragedies of his own life and the pettiness of the contemporary scene.”

Ross Jr. assisted his father with historical projects, but according to Larry was “not his father’s puppet at such performances” and “never approached his father’s ease of performance and lack of self-consciousness.”

Ross Jr. was born in Bloomington, Indiana and moved to Fort Wayne. When he was 9-years-old the family returned to Bloomington and his literary dreams took root.

According to an Indiana Public Media article (IPM), Junior attended Indiana University, where he was known as “A+ Lockridge,” graduating with the highest GPA ever awarded by the school (4.33). Scarlet fever precluded his plan to join IU’s English Department, leaving him bedridden for eight months. He was later accepted as at doctoral student at Harvard University, where he began his famed novel.

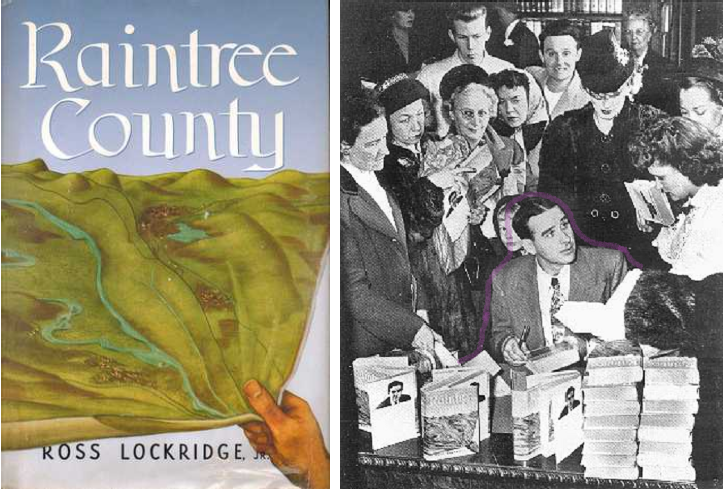

According to an Altered Books Arts article, he withdrew from his studies and taught at a nearby college, so he could focus on his literary magnum opus. The IPM article reports that he studied abroad in Europe in 1934, where he “first had the vision of writing a novel that would draw upon the would-be literary heritage of his maternal grandfather, a schoolteacher and poet who had lived in Indiana’s Henry County.” This evolved into the character of John Shawnessy, who after losing his wife went on to fight in the Civil War, attempted to write the Great American Novel, and ended up in the fictional Raintree County.

Although Johnny had his successes, the character flashed back in memory wondering about the country’s future. He is influenced by several cultural concepts, one of which is to find the legendary Rain Tree, supposedly planted somewhere in the Raintree County by the celebrated Johnny Appleseed, who is buried in Allen County. The tree Lockridge sought to feature is based on a real Golden Rain Tree, which blooms in the summer with subtle yellow flowers that drop like a raining of yellow pollen dust.

In addition to Allen County, Monroe County is represented in the book. Larry noted, “We have county fairs and patriotic programs and outdoor sex and footraces and weddings and temperance dramas and rough talk . . . all of this he picked up in the culture of Bloomington” (IPM). Ross Jr.’s wife, Vernice, did the final typing of the novel, an 18 month endeavor and, unlike many writers, her husband gave her full credit for her help in constructing the 1060-page novel.

Altered Books Arts summarizes the novel’s themes, stating:

“In the course of its thousand pages philosophy, religion, sex, and history all flow together in a narrative that spans 40 years, recollected in a single day. In some ways it is an Indiana Ulysses, though Lockridge said that whereas Joyce wished to make the simple obscured, he wished to make the obscure simple. When it came out Thomas Wolfe and Walt Whitman were frequently cited for comparison, but it seems closer to in technique and feeling to the panoramic narrative of John Dos Passos’ U.S.A.“

Ross Jr.’s labor of love was met with much anticipation from his publisher, Houghton Mifflin. However, in order to win MGM’s high-profile contest for best new literary work, an award of $150,000, he was pressured to revise and cut several sections from his masterpiece. His likely selection as Book of the Month club winner, meant that he had to make many more extensive cuts. He conceded reluctantly and worked tirelessly to trim it for publication. His publisher Dorothy Hillyer wrote “Ross was quite capable of fussing eighteen hours a day over that manuscript. He was in love with it, almost sexually.” (He ended up cutting out a 356-page dream sequence, which is retained at Bloomington’s Lilly Library).

These compromises, the killing of his darlings, so to speak, and the completion of his life’s work plunged him into a deep depression. Despite generally rave reviews about the novel and winning MGM’s literary award, Lockridge’s depression worsened and he returned to Bloomington. His son regarded this as a mistake, “not because of Bloomington’s particular atmosphere but because it felt to him as if he had come full circle. . . . It was the symmetry of fate that he was returning home to die.”

Larry noted that his father began exhibiting bizarre behavior, inspecting knives in the kitchen and opening and closing cupboards, claiming he was “looking for a way out.” Public backlash about the book’s sexuality and irreverence, especially by his Bloomington neighbors, made him doubt the quality of his work and worsened his fragile state. (According to IPM, the publication of his neighbor Alfred Kinsey‘s Sexual Behavior in the Human Male promoted Lockridge to quip “It seems Mr. Kinsey and I have succeeded in making Bloomington the sex center of the universe”).

Ross Jr.’s father hoped to combat his son’s malaise with recitation, the memorization of the Declaration of Independence, hearkening back to their old historical endeavors. Ross Jr. reluctantly entertained his mother’s Christian Science ministrations, but remained in a debilitated state. Ross Jr. was not alone in his distress; his cousin Mary Jane Ward suffered from mental illness, which she depicted in her successful autobiographical novel The Snake Pit.

Witnessing her husband’s ongoing suffering, Vernice convinced him to seek treatment at Indianapolis’s Methodist Hospital, where he underwent electroshock convulsive therapy and insulin-induced coma. Further distressed and embarrassed by the procedures, he gave staff the impression he had recovered and was released.

According to Larry, his father tried to write a second novel, a “thinly disguised autobiography, from Fort Wayne days to the present.” He had planned to begin the story with his young brother’s tragic death and,

“the tranquil Avenue of Elms, Creighton Avenue in Fort Wayne, whose backdrop was the Great War. It is in this city that his brother Bruce drowns, that his house catches fire, that there is a great strike at the mill, that he falls in love with Alicia Carpenter, that he decides to become a writer, and that through ‘the brutality of fate’ his personality is set by the age of ten.”

He was never able to finish a second novel. On March 6, 1948, the day after Raintree County was declared a number one best seller, Ross Lockridge, Jr. took his own life at age 33 in Bloomington. Unable to locate her husband, Vernice went out to their garage. There she discovered his limp body in the running car, a vacuum cleaner hose piping exhaust into the car. The death of the new literary star stunned the nation, attracting over 2,000 to his funeral and prompting an obituary on the front page of the New York Times.

In 1957, MGM produced a big screen depiction of Raintree County, featuring Montgomery Clift, Elizabeth Taylor, and Eva Marie Saint.

Weeks after the death, Vernice found a note written by her husband, stating “‘Dearest, Have gone for early morning walk to clear head. Love, Ross.” On the back side he wrote:

“The purpose of Raintree County is to present life in its many-sided variety with idealism triumphant. An irreverent character in a book does not mean an irreverent book. In any event it is an old and good rule that every reader is entitled to his own opinion of a book.”

Surviving the death of a second son, Ross Sr. passed away a few years later in 1952.

Learn more about the remarkable Lockridges with Larry Lockridge’s 1994 Shade of the Raintree: The Life and Death of Ross Lockridge, Jr., author of Rain Tree County.

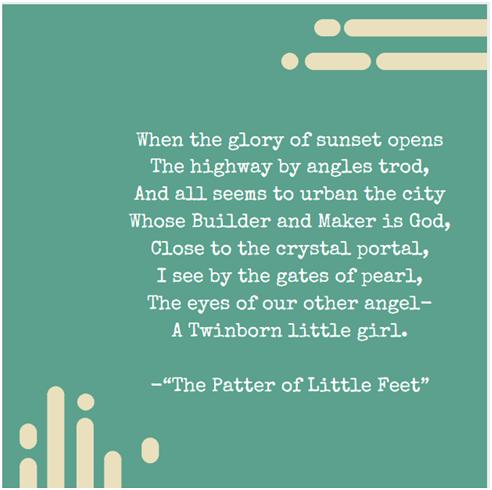

The poem goes on to describe the mother’s longing that she will someday reach heaven and hear the patter of her daughter’s feet on heaven’s floor.

The poem goes on to describe the mother’s longing that she will someday reach heaven and hear the patter of her daughter’s feet on heaven’s floor.

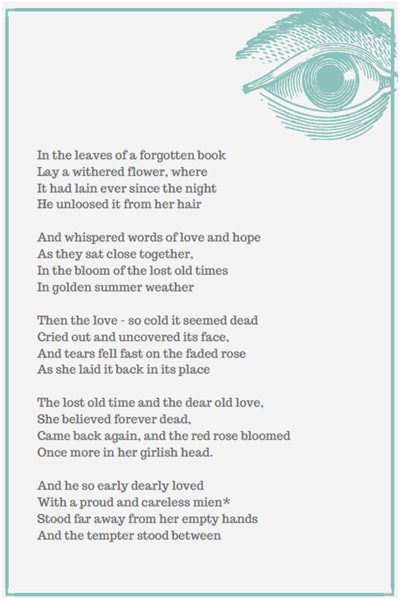

Interestingly, this poem does not seem to have raised any speculation regarding Lew’s faithfulness to Susan.

Interestingly, this poem does not seem to have raised any speculation regarding Lew’s faithfulness to Susan.