“In our endeavors to attain social justice, we cannot afford the

destructive luxury of discriminating against one another.”

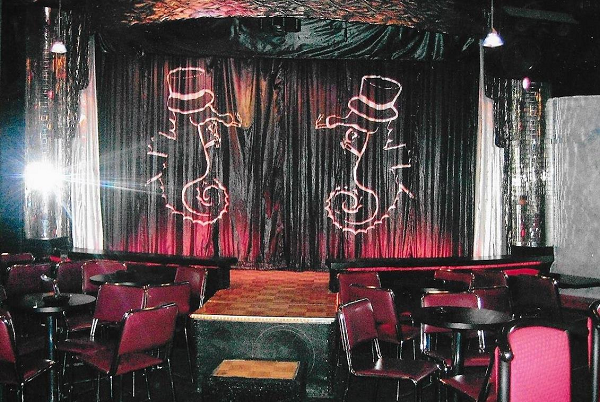

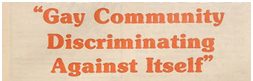

Justice, Inc., an LGBTQ+ rights organization, issued this statement in 1989 after some gay bars in Indianapolis refused to serve cross-dressing and transgender individuals.[1] The city’s queer community had already encountered and protested numerous challenges posed by law enforcement, including police harassment, surveillance of cruising sites, and possible prejudiced police work as homicide rates increased for gay men. Although gay bars afforded a degree of shelter from discrimination, not all were afforded the opportunity to patronize them.

While examining Indiana’s gay newsletter The Works, I came across recurring incidents of discrimination within Indianapolis’s queer population. In 1973, outspoken transgender rights activist Sylvia Rivera drew attention to these incidents on a national level at New York City’s Christopher Street Liberation Day Rally. Rivera had helped found the Gay Liberation Front and, with her friend Marsha P. Johnson, the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) in NYC, which provided desperately-needed shelter and food for homeless trans youth.

In addition to advocating for people of color and the impoverished, Rivera advocated for white, middle-class men and women jailed because of their sexual orientation and/or gender identity. She also fought for the women’s liberation movement. Despite this, she was shunned for her attempts to include trans individuals in the broader gay rights movement. She famously addressed this ostracism after pushing her way on stage at the Liberation Day Rally. There, she passionately addressed the crowd, stating “I have been beaten. I have had my nose broken. I have been thrown in jail. I have lost my job. I have lost my apartment for gay liberation and you all treat me this way?” Her speech was met with a smattering of jeers and applause.

However, marginalized individuals within the queer community have been increasingly recognized through public artwork, Netflix documentaries, and seminars like The New Republic’s recent “Sex Workers as Queer History”. Cecilia Gentili, founder of Trans Equity Consulting and transgender actress in the Netflix show POSE, recalled in the seminar that gay men had significant power over transwomen and if you “weren’t fabulous enough” then you couldn’t get in the bar. She likened these experiences to the “criminalization of gender.” In this post, I examine similar incidents in Indianapolis, as well as strategies employed by the victims of discrimination to help secure rights for all.

Kerry Gean, dressed as the “woman I am deep inside of my biological male self,” and friends went to the Varsity Lounge in February 1989. After they were seated, their server singled out Gean with a request for identification. The server then informed her that she was breaking the law because the photo on her I.D. did not identically match her face. Humiliated and hurt, she returned home, changed into “male” clothes, and upon return was immediately served. After Gean’s experience, she asked readers in an editorial for The New Works News “Are we now turning against ourselves? Can we forget what it feels like to be barred from a public place by the owner, or even a bartender, who has some reason to hate us for the hard but true choices we have made?”[2]

By June, things were no better for Roberta Alyson, described by The Works as a “pre-operative transsexual.” Alyson was denied entrance to the gay bar Our Place on the grounds of not meeting dress code and identification not matching Alyson’s face, despite having a doctor’s note confirming the necessity of dressing as a woman. Bar officials got an off-duty officer who worked security to check the 31-year-old’s ID. He crumpled up the doctor’s note and Alyson “regrettably began to panic,” walking away from the parking lot. When the officer pursued and arrested Alyson, who later said one of the back-up officers was abusive and tried to lift Alyson’s skirt. Alyson was charged with and fined for fleeing an officer.[3]

Alyson addressed the implications of such discrimination in a letter to the editor of The New Works News, noting Our Place’s dress code “flies in the face of the Stonewall Riots and sends a terrifyingly repressive message to the ‘straight’ community.” Alyson noted, “There were ‘genetic females’ in the bar on the night I visited it” and asked “Am I somehow more of a ‘threat’ to the bar’s image than a woman born?” Reflecting Gentili’s recollection, Alyson wrote “We, the greater gay community, are seeing a disturbing trend in that ‘gay rights’ seem only to apply to gays and lesbians who ‘fit in.’” Simply put, “Gay rights are human rights, and they apply to all of us!”[4]

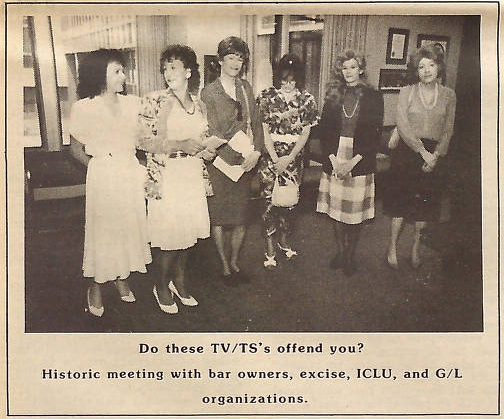

Indianapolis police liaison Shirley Purvitis, one of the first to be appointed in the nation, organized a meeting to try to resolve issues between “certain segments of the gay community” and local gay bars. These bars included Our Place, 501 Tavern, and The Varsity. She noted later that “one of the most effective ways to fight discrimination was to ‘shut up and listen to what the other person has to say.’” Bar Owners, members of the Indiana Civil Liberties Union and Justice, Inc., IPD vice officers, and members of the Indiana Crossdresser Society (IXE) attended the meeting, which was, “as expected, confrontational from beginning to end.”[5]

As to claims that individuals were being denied entrance due to discrepancies between their photo I.D. and their physical features, Excise Chief Okey stated that “the only requirement that excise has for a person being served alcohol is that they be 21 years of age or older. . . . crossdressing, either male or female, is not grounds for refusal of service.” Other bar owners stated blatantly that they refused to admit these patrons, not because they feared breaking excise laws, but because they intended to “‘preserve the established atmosphere of their bars.'”[6] A 501 Tavern spokesperson stated that these individuals “‘were not wanted there,’ and if they had been admitted violence might have resulted. The bar owners also voiced the fear that if they admitted people in drag their regular patrons might leave.” Gay TV producer Gregory McDaniel denounced this reasoning, stating, “‘What I’m hearing now is exactly what I heard 20 years ago when attempts were being made to keep blacks out of Riverside Park and other public places.'”[7] Aside from being morally wrong, McDaniel alleged this discrimination halted momentum in the broader fight for gay equality, noting, “The wire services have picked up these stories. This shows the dominate [sic] society that we are not unified and that they are safe in oppressing us.”

David Morse, manager of Our Place, stated at the meeting that he felt “‘very much trapped in the middle.’” He tried to reconcile the needs of both parties, “perhaps naively,” by establishing the dress code and I.D. policy. However, he noted that he “‘learned many lessons'” from the ensuing discussions. [8] Perhaps fear of losing the bars they fought so hard to establish—whether by mistakenly breaking excise laws or drawing unwanted attention to the establishment—owners implemented discriminatory policies. Unfortunately, the meeting to discuss these policies ended without much resolution.

IXE met separately with Justice, Inc. to address the issue and one observer at the meeting speculated that “perhaps one reason that the crossdressers were causing such a stir in the ‘male’ bars” was because they looked:

‘too good and too much like natural, normal women and a far cry from the narrow gay-oriented perception of what “drag queens” look like. Perhaps some of the shakier ‘male’ egos couldn’t handle this unaccustomed image.’ [9]

By September, there seemed to be a bit more acceptance, as Our Place admitted Roberta Alyson, who by then had two pieces of “‘official’ feminine'” identification. The newsletter reported that Tomorrow’s and Jimmy’s had also been more welcoming.[10] McDaniel also commented that the The New Works News‘s extensive coverage of the discrimination showed that the community could be “introspective and self-correcting.”[11]

Sharon Allan, of IXE, decided to affect change by sitting down with bar employees. She met with Brothers manager Michael David to ask if their policy that identification had to match one’s appearance was implemented uniformly. After he said yes, Allan informed him that she “had been in the bar four times, after work and in a tie and had never been asked for ID.” Allan reported to the New Works News that “Michael immediately saw the lack of universality in their policy and promised to speak with the owner at the next staff meeting.”[12]

Capitalizing on the positive momentum, Justice, Inc. hosted the second “Discrimination Within the Gay Community” workshop in December.[13] While the turnout was low, and bar employees noticeably absent from the meeting, attendees reported that most bars had “reversed” their discriminatory policies. At the meeting, Gary Mercer, of Goshen, quipped “’Before you judge other people in the gay community, you better walk a mile in their pumps.’” Gay Cable Network’s Eric Evans agreed, noting that “‘discrimination is usually the result of ignorance.'” He suggested ongoing education for “both the gay and straight communities.” This, he said, could be accomplished through television programming and by forming a Gay Community Center.[14]

While awareness and dialog did not end prejudice entirely within Indy’s queer community, reported incidents diminished in The New Works News. Genny Beemyn notes in “Transgender History of the United States,” that in the early 1990s a “larger rights movement” emerged, “facilitated by the increasing use of the term ‘transgender’ to encompass all individuals whose gender identity or expression differs from the social norms of the gender assigned to them at birth.”[15] Still, activists fought an uphill battle for inclusion, as the “March on Washington” steering committee voted overwhelmingly to leave them out of the 1993 “Lesbian, Gay, and Bi Equal Rights and Liberation” march, despite support from bisexual allies.[16]

Discrimination and violence against transgender individuals, especially those of color, endures, although largely waged by those outside of the queer community. However, public recognition of those marginalized within the community has increased, to some extent. In 2019, New York City announced it would honor drag queens and transgender rights activists Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson with monuments. Scott W. Stern and Charles O’Malley noted in their 2019 “Remembering Stonewall as It Actually Was—and a Movement as It Really Is” that the decision:

reflects a dawning awareness (among those in positions of power) that the LGBTQ movement was always more diverse, more radical, and more closely connected with other social movements than is commonly believed.

Along with the statues of Rivera and Johnson, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo announced in August 2020 that the Marsha P. Johnson State Park, located along the East River, would be dedicated. This will be the first state park in the US honoring an LGBTQ+ individual, as well as a transgender woman of color. Stern and O’Malley argue that we should examine and commemorate those at the margins of equal rights movements not simply for history’s sake, but because “More accurate renderings of the past inform the way we act in the future; they inform whose lives we prioritize in the present.”[17] That is why we should be aware of Roberta Alyson and Kerry Gean, whose determination to transform humiliating experiences into policy change helped open the door to acceptance for other transgendered and cross-dressing individuals in Indianapolis. They remind us of the importance in engaging in conversations with “the other.”

*The professional study of LGBTQ+ history is relatively new. We welcome feedback regarding accuracy and terminology, especially given the challenges in locating primary sources and the evolving conception of what comprises the queer community. We are especially interested in documenting lived experiences from a variety of perspectives.

[1] “Justice Investigation Calls for Uniform Bar Policies,” The New Works (October 1989): 8, accessed Chris Gonzalez GLBT Archives, IUPUI Library.

[2] “Varsity Drag,” The New Works News (July 1989): 3, accessed Chris Gonzalez GLBT Archives, IUPUI Library.

[3] “O.P.’s Dress Code Causes Arrest of TS: Transsexual Arrested Trying to Gain Admittance,” The New Works News (August 1989): 1, 7, accessed Chris Gonzalez GLBT Archives, IUPUI Library.

[4] Roberta Alyson, “Crossdresser’s Visit to Our Place,” The New Works News (July 1989): 3, accessed Chris Gonzalez GLBT Archives, IUPUI Library.

[5] “O.P.’s Dress Code Causes Arrest of TS: Transsexual Arrested Trying to Gain Admittance,” The New Works News (August 1989): 1, 7, accessed Chris Gonzalez GLBT Archives, IUPUI Library.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] “IXE Meets with Justice,” The New Works News (August 1989): 7, accessed Chris Gonzalez GLBT Archives, IUPUI Library.

[10] Gregory McDaniel, “Courageous Clear Thinking,” The New Works News (September 1989): 6, accessed Chris Gonzalez GLBT Archives, IUPUI Library.

[11] Ibid., 3.

[12] Sharon Allan, “No Discrimination Intended at Brothers,” The New Works News (October 1989): 3, accessed Chris Gonzalez GLBT Archives, IUPUI Library.

[13] “Justice Discrimination Workshop,” The New Works News (December 1989): 6, accessed Chris Gonzalez GLBT Archives, IUPUI Library.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Genny Beemyn, “Transgender History of the United States,” in Laura Erickson-Schroth, ed., Trans Bodies, Trans Selves (Oxford University Press, 2014), p. 28, accessed umass.edu.

[16] Ibid., 29.

[17] Scott W. Stern and Charles O’Malley, “Remembering Stonewall as It Actually Was—and a Movement as It Really Is,” The New Republic (June 24, 2019), accessed newrepublic.com.

[18] Ibid.