The United States faces an abundance of national security concerns in 2016, ranging from North Korean nuclear testing to Islamic State nuclear ambitions. Russia was notably absent from the 2016 Nuclear Summit, which was “aimed at locking down fissile material worldwide that could be used for doomsday weapons,” while maintaining the largest stockpile of nuclear weapons in the world. These concerns prompt a question that originated in the early Cold War period: how can a nation prevent nuclear attack?

During WWII, the U.S. detonated the first nuclear bomb over Hiroshima, Japan on August 1945, catastrophically damaging the city. The postwar 1949 explosion of a Soviet atomic bomb ignited fears of the American public about what Anne Wilson Marks dubbed in an article for the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, a “new Pearl Harbor.”

When most think of early Cold War civil defense they recall bomb shelters and “duck and cover” drills. However, President Dwight D. Eisenhower implored Americans in a 1953 advertisement to “Wake Up! Sign Up! Look Up!” to Soviet airplanes potentially escorting an atomic bomb over the U.S. He encouraged them to do so through a collaborative program with the U.S. Air Force called the Ground Observer Corps, established in 1949.

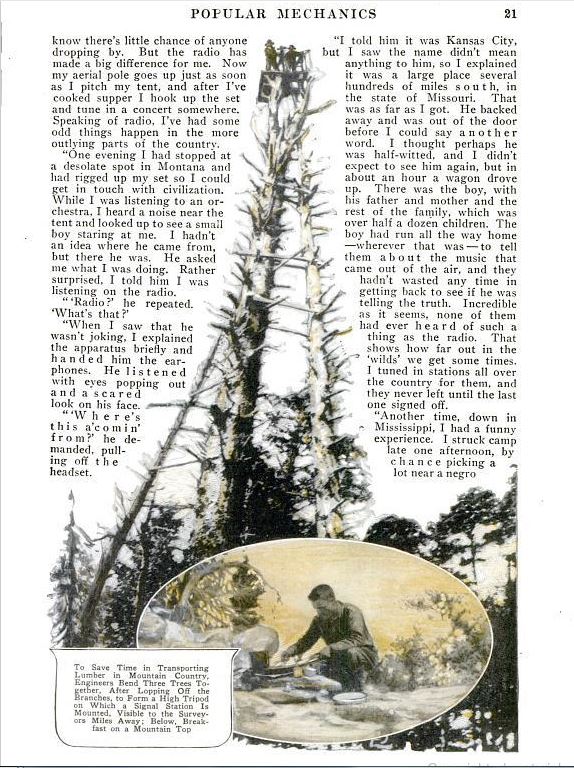

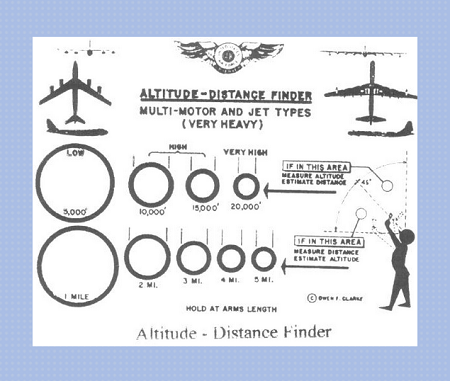

In the GOC, civilian volunteers were encouraged to build watchtowers in backyards and community centers, and to survey skies from existing commercial structures. Utilizing a telephone, binoculars, observation manual, and log of duties, civilians searched the skies for airplanes flying lower than 6,000 feet, which could evade radar detection. At the sight of a suspicious, possibly nuclear-bomb-toting plane, civilians were to telephone their local filter center, staffed with Air Force personnel, who could then direct the plane to be intercepted or shot down.

This collaborative civil defense program involved approximately 350,000 observers, made up of families, prisoners and guards, the youth and elderly, the blind and handicapped, and naval and USAF personnel. In 1952, the Ground Observer Corps operated 24-hours each day and became known as Operation Skywatch.

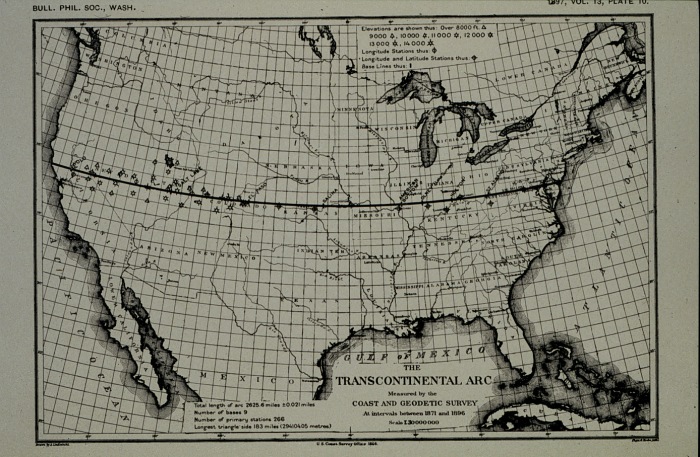

Scientists estimated that Soviet aircraft would emerge over the North Pole, raising questions about Indiana’s vulnerability. Governor Henry F. Schricker warned in The Indiana Civil Defense Sentinel that “Hoosiers should be alert to protect vital Indiana war industries if hostilities should break out.” Indiana officials worried that Lake County, part of Chicago’s urban industrial area, could be a site of an enemy attack. Concerned Indiana citizen Thomas H. Roberts wrote to Gov. Schricker that his family lived in “the highly industrialized Calumet area. I am sure you are aware that this area is a likely target for enemy attack.”

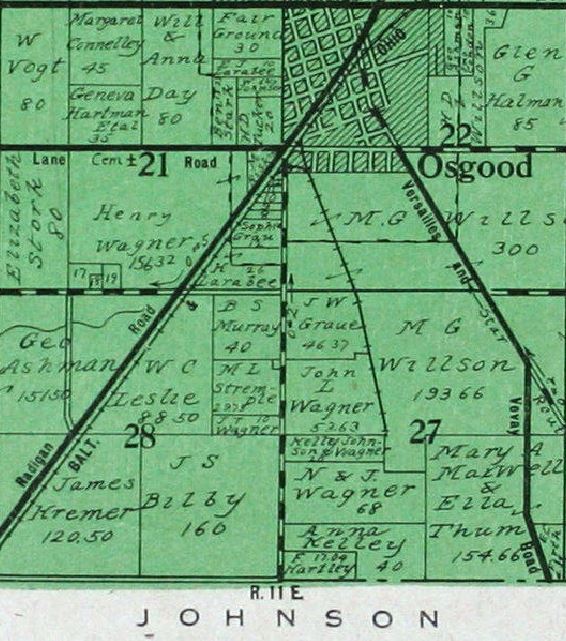

According to articles and letters sent to Schricker in 1950 from other governors, GOC planning advanced more quickly and decidedly in Indiana than other participating states. Unsure as to how to proceed after a Washington planning conference, Illinois Governor and future presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson appealed to Schricker for advice. Schricker detailed Indiana’s planning process for Stevenson, stating that he would first contact every mayor, town board president and all “peace officers on every level throughout the state.” Days after the meeting, the Department of Civil Defense for Indiana compiled a list of observer posts for each county.

On March 16, 1950, a mock air attack over Indiana illustrated the shortcomings of radar, as B-26 bombers flown by members of the Air National Guard of Indiana, Missouri and Illinois proceeded “completely undetected” by radar at Fort Harrison, the state’s only warning facility. Following the alarming mock air attack, municipal and county officials named Civil Defense Directors in 51 Indiana counties, who established observer posts in the northern two-thirds of Indiana. By late 1950, as the Korean conflict grew, the Air Force had partially constructed a filter center in South Bend, Indiana.

Historian Jenny Barker-Devine wrote in 2006 that rural residents were likely not targets of atomic explosions, but that federal civil defense agencies sought their help because “rural families also served as custodians of democracy and could prevent any type of socialism or communism from taking hold in local, state, and national governments.”

Diligent rural citizens, such as Larry O’Connor of Cairo, Indiana, organized movements to establish local GOC towers. O’Connor, a World War II Navy veteran and owner of Cairo’s only store (attached to his house), designated it the small community’s initial observation site.

In an interview with the author, Cairo resident James Haan shared that the post was necessary because Cairo was located along a line of beacon lights that could guide the enemy to industrial centers in Chicago. In 1952, building began on the Cairo observation tower and the local Rural Electric Membership Cooperative (REMC) donated and set the tower poles. Local merchants from Lafayette and the town of Battle Ground donated materials, and residents in surrounding areas furnished labor. Between 90 and 120 volunteers from surrounding areas volunteered at the Cairo tower. Haan states that volunteers worked in two-hour shifts and that he and other farmers worked all day in the fields, while female family members manned the towers, and the men volunteered throughout the night.

The Lafayette Journal and Courier claimed that Cairo’s tower was one of the first freestanding towers constructed over the ground. According to O’Connor, it was “the first G.O. Post officially commissioned by the U.S.A.F. in the U.S.A.” Commanding Officer of the South Bend GOC detachment, Lieutenant Colonel Forest R. Shafer, mentioned in a letter “I can verify that the tower constructed at Cairo, Indiana was the first of its kind within my jurisdiction but cannot confirm that it was the first in the United States. However, I am certain it was among the very first, at least.”

More research should be done to verify these claims, but it is clear that the recognition of USAF personnel and public officials gave residents a sense of pride in their contributions. Haan recalled “We had some representatives down here and felt pretty good about it.” He felt that the GOC tower made “a pretty important place out of it [Cairo]. There was a lot of business up there, a lot of people coming and going and working on the tower. And there was for days and days and days a lot of people up there.”

Under O’Connor’s direction, local residents held a dedication for the tower in 1976, commissioned a moment featuring limestone volunteers, and got the tower listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The site was later commemorated with a historical marker.

The GOC is now long forgotten, as demonstrated by the Cairo tower, once so revered by the community for decades, but now in decay. As with many civil defense programs of the 1950s, the GOC has been deemed a quirky, superfluous program, constructed by an overly-paranoid people. However, the GOC established a model of national defense that solicited the participation of the general public. It served as an opportunity for families, neighbors, and community members to spend quality time together through the shared objective of improving national security.

On January 31, 1959, the Secretary of the Air Force announced the termination of the program due to the improvement of detection radar and inability of civilians to detect increasingly technical Soviet missile system. The Indiana Civil Defender almost wistfully noted that the U.S. “is geared to the substitution of machines for manpower . . . and we accept this theory of progress.” The bulletin lamented the conclusion of the program, but congratulated its participants for successfully deterring attack, going so far as to claim the GOC may have been “the one final deterrent to an attack on the country by a calculating enemy.”

As national attention returns to security concerns, the question remains: how does a country stop the detonation of a nuclear bomb? An NPR correspondent recently contacted the author about the potential for a piece about these Cold War watchtowers.

Despite precarious national security issues, IHB is pleased to report that the Cairo marker has recently been repainted. We are grateful to the Sigma Phi Epsilon Fraternity at Purdue University and Bruce Cole and his sons for their work to preserve the legacy of those vigilant Indiana citizens.

Learn more about the GOC and Cairo tower with the author’s master’s thesis.

Want more towers? Check out our blog posts about Hoosier surveyor Jasper Sherman Bilby, whose Bilby Tower was foundational to modern GPS.