In addition to the struggles of daily life, Black Americans had to wage an often losing battle to secure suitable education for their children. They had historically been deprived of that which affords an understanding of one’s rights and enables one to secure a livelihood. Crawfordsville’s Lincoln School embodied this decades-long fight. However, like other segregated schools, students went on to achieve success and make a name for themselves, despite inequities.

After the Civil War, education for Black pupils was conducted in piecemeal fashion. In an article for the Indiana Magazine of History, Professor Abraham C. Shortridge noted that around 1862 the Indiana State Teachers’ Association began to lobby for “colored schools,” but lawmakers failed to take action. Shortridge lamented that it looked as if in the ensuing years:

the black children were doomed to run the streets for another term of two years while their fathers and mothers continued to pay their taxes, by the aid of which the children of the more favored race were kept in school ten months of the year.

However, in 1869, after much deliberation at a special session called by Governor Conrad Baker, the Indiana General Assembly approved an act that admitted Black children to public schools.

The new law stated that township trustees “shall organize the colored children into separate schools, having all the rights and privileges of other schools of the township.” Should there not be a large enough population to warrant a separate school, the law stated that “Trustees shall prove such other means of education.” According to historian David P. Sye, “other means” often included sending children to “private school or in some cases giving them books, giving money back to the parents, or just nothing. The courts did not help in this situation.” This was the case in Crawfordsville, as Black children were educated privately, at institutions like Bethel AME for years after the act was ratified.

The Crawfordsville Weekly Journal reported in the 1870s that Black children studied under Harmon Hiatt in the church’s basement. Little is known about what pupils studied, but it is clear that school conditions were poor, as the Weekly Journal reported in 1873 “complaints are made that the old church in which the school is held is not properly heated during the cold weather.” The school board trustees did nothing to remedy this. In fact, eight years later, 126 students attended the house, which was designed to accommodate only 48.

In the summer of 1881, the city council voted to build a school for Black children at Spring and Walnut Streets. Students attended first through seventh grade (although at times eighth grade was offered) at Lincoln School before attending integrated Crawfordsville High School. Lincoln pupils studied traditional grade school subjects like arithmetic, reading, and writing. However, much like at the AME church, school conditions were poor and the teacher-to-student ratio abysmal.

Black residents refused to accept this institutionalized inequality. According to the Crawfordsville Review, in April 1892 parents submitted a complaint to the school board, stating that they would withdraw their children should there be no remedy to Lincoln’s “proximity to two or three houses of ill fame in the neighborhood, and the inmates of which have no regard for the ordinary decencies of life and set dangerous examples for children.” Trustees responded that they could secure “no better” accommodations.

The following year, the Crawfordsville Daily Journal reported that conditions had not improved, alleging that the principal was abusive and that it was difficult to find qualified teachers, resulting in many students being unable or unwilling to come to school. The paper noted that, “in view of the fact that all the neighboring cities have race co-education,” the school board was considering transferring Black children to the white elementary schools. Just weeks later, the Journal reported the board decided to maintain segregation and remedy the issue by appointing a “brawny white teacher.”

The Black community challenged this “solution” in 1894, gathering at Second Baptist to discuss Lincoln School, which was “quite inferior in many respects to the other schools of the city,” according to the Crawfordsville Daily Journal. They felt that it was a “farce” to tax the community, only to provide such abysmal education. Meeting attendees formed a committee to “to wait on the Board of Trustees, laying before the body our grievance.”

The trustees remained unmoved by their formal petition, spurring another strategizing meeting. Attendees advocated for either appointing Black educators and administrators—as had been the case in previous years—or sending children to white schools. Neighboring towns, like Lebanon, Greencastle, and Frankfort, had successfully integrated schools. However, meeting attendees preferred the appointment of Black teachers, stating:

It needs no argument to prove that for colored children, colored teachers are manifestly superior to white teachers since the latter have no sympathy in common with colored children, do not associate at home, at church or on the street with colored patrons and are diametrically opposed in conduct and natural feeling. (Crawfordsville Weekly Journal)

They won a small victory when the board appointed Black educator Mr. Teister to “take charge” of Lincoln.

Despite parents’ persistence, the school experienced a shortage of teachers and its facilities remained inadequate until its closure. In oral histories with students who attended in the 1930s and 1940s, many recalled there was only one educator to teach seven grades. Not only were there not enough teachers, but far from enough space. Madonna Robinson recalled:

It was cramped up, because they would have like two rows of maybe the third and fourth grade here, and then in the other room was the fifth and sixth grade, you know, there were two classes in one room, very cramped, no windows in the front, just had windows in the back of the school, no windows in the front. It wasn’t much fun to me.

Some students felt unprepared for high school due to the disparities at Lincoln, and struggled to catch up to other students.

Alumnus Elsie Bard told interviewer Eugene Anderson “The teachers had quite a few children to really be teaching, and couldn’t devote their full time to them right, but that’s what they had to work with, so they did the best they could.” The lack of supervision meant that children often played the piano, rehearsed plays, and acted. Madonna Robinson recalled “It just wasn’t school to me. . . . It just seemed like a place to go practice plays.” Similarly, Leona Mitchell remembered that teachers liked to have “little plays and dramas and things and we learned to sing,” adding “we were always doing oh some kind of little skit.” Perhaps this creative, formative environment helped foster the musical prowess of jazz greats Bill Coleman and Wilbur de Paris, who achieved national success and performed with legendary recording artists.

De Paris learned to play trombone as a child and performed in the Crawfordsville High School band. He later relocated to New York City. According to the Syncopated Times, by the 1930s de Paris recorded with jazz greats Benny Carter and Louis Armstrong. In the 1950s, his New New Orleans Jazz Band had become “one of the most exciting groups of the era.” His brother, Sidney—likely also a Lincoln School alum—played in his band and was a successful musician in his own right, recording with artists like Jelly Roll Morton. Arguably, Wilbur achieved greater success than his brother and a 1958 Indianapolis Star article described him as “possibly the world’s greatest jazz trombonist,” having “performed with almost every legendary jazz figure of the century, and played in almost every spot in America where jazz was allowed to seep in or burst out.”

Bill Coleman also achieved acclaim as a jazz trumpeter. He and the de Paris brothers met as students at Lincoln. Coleman gained success playing in Europe and, according to his Washington Post obituary, spent most of his life in France as “’one of the numerous black musicians here as refugees from segregation.’” He played with famous performers like Fats Waller and Billie Holiday.

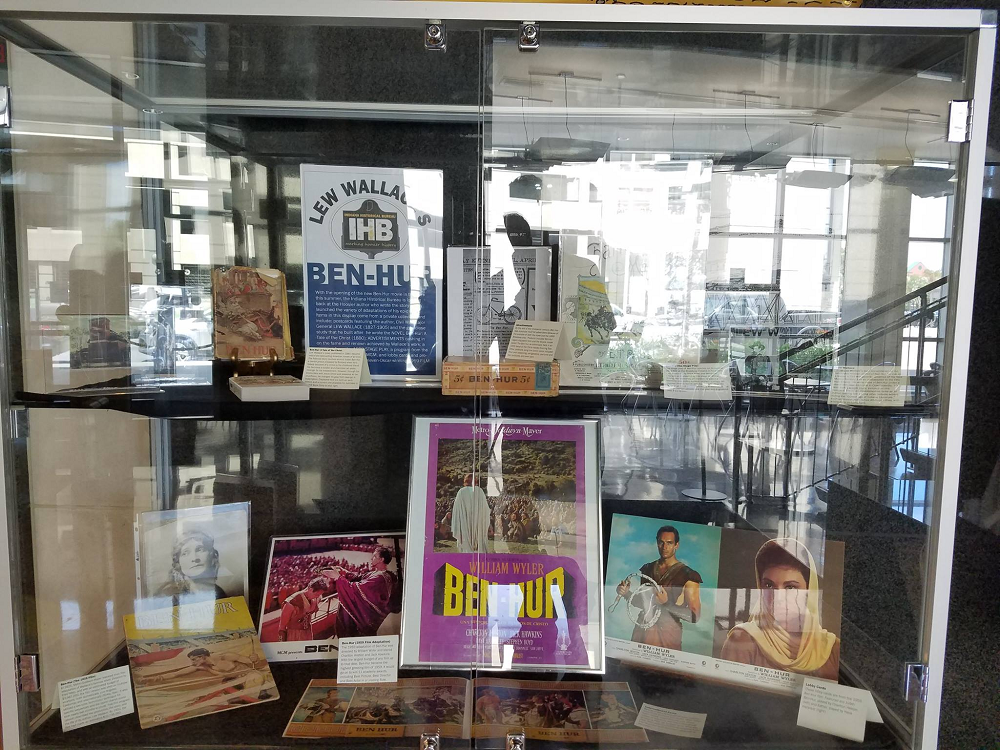

Alum Blanche Patterson achieved local success in music and was an officer of the Indiana State Association of Negro Musicians. Her obituary stated she “developed a state-wide reputation as a musician” and “organized a program which brought numerous Negro instrumental and vocal music groups to Crawfordsville.” Patterson was likely better known for her business prowess, owning and operating the Petite Beauty Shop in Crawfordsville’s Ben-Hur building, described by the Indianapolis Recorder as “one of the finest beauty parlors in the State.” Additionally, she was a member of the National Beauty Culture League of Indiana and later became a chiropodist.

In addition to the arts, Lincoln students excelled at athletics under the guidance of principal George W. Thompson, a former Indiana University athlete. According to the Indianapolis Recorder, in 1913 the school’s baseball team won all of its games and its track team earned the highest number of points among all Crawfordsville grade schools. The paper reported that white schools had “refused to meet them on the field, but patience and diplomacy by Prof. Thompson won over prejudice and when our boys won in the recent meet . . . Wilson school boys (white) placed a card in the local papers praising them for their fairness and superiority.”

According to local historian Charles L. Arvin, Black residents began moving to the eastern part of Crawfordsville. In 1922, Lincoln School relocated to South Pine and East Wabash Avenue to accommodate them. Alumnus Patty Field stated that many moved to that side of town for job opportunities at factories.

The school closed in 1947 and the building was later converted into a recreation center for the Black community, and it served as a meeting space for the Baptist Church and Mason’s Lodge. By the 1970s, Parks and Recreation Department monthly reports showed that nearly 1,000 people used the center’s playground in just one month, and that thousands attended its summer program. In addition to two basketball courts and workout equipment, the center had pool tables, swings, slides, and a softball diamond. Field recalled “even when we got older and had kids, Lincoln [recreation center] was our safe place.” However, the Parks Department decided to close it down in 1981. Lincoln alum Madonna Robinson described the decision’s impact on the Black community, saying “it was really a sad thing that they took it away from them, because they don’t have any where to go now.”

However, Lincoln’s legacy as a site of refuge, community, and self-advocacy will not be forgotten. In 2025, with the help of local partners like Shannon Hudson, IHB will install a state historical marker commemorating the school. Check back for dedication details.

For sources used for this post, see our historical marker notes.

Learn more and see photos of Lincoln School via “Memories of Crawfordsville’s Lincoln School for Colored Children,” a collaboration between the Carnegie Museum of Montgomery County and the Robert T. Ramsay, Jr. Archival Center at Wabash College.