Indiana is a sports state through and through. From our long history with Hoosier Hysteria and March Madness to our deep passion for the football team that arrived in the dead of night to the checkered flags dotting the capital city every May, it’s clear we love our sports. While many Hoosiers are familiar with our love for basketball, football, and racing (among many other popular pastimes), there’s also a long history in the state of Indiana with another much less known and perhaps more controversial sport:

Roller Derby.

Over the long decades of the sport’s existence, Hoosiers had a complicated relationship with Roller Derby. They loved it and found it immensely entertaining, but was it true sport? Was it more of an entertainment spectacle? Could Roller Derby scores grace the sports page of the Indianapolis Star or the Indianapolis Times the same as the box scores for other sports? Not everyone thought it should, yet thousands of Hoosiers still clamored for tickets whenever the Roller Derby wheeled into town.[i] There was just something deeply amusing about the fast-paced skating and amped up action of the mad whirlers as they skated around and around the banked track. The Roller Derby offered fans something that no other full contact team sport did: women competing on par with men, and for that reason, the Roller Derby was both beloved and spurned.

Roller Derby, in its modern form, was born out of the struggles of the Great Depression. There is a long history in the United States of various roller-skating races and marathons, and many of them were even called roller derbies. However, in the 1930s, an entertainment promoter named Leo Seltzer decided to try his hand at putting on a roller derby. He had recently become the main leaseholder on the Chicago Coliseum and after hosting a series of walkathons and danceathons was convinced that these attractions couldn’t hold the long-term interest of paying crowds.

Yet deep in the throes of the Depression, he knew he needed cheap entertainment that the average American could relate to and spend some of their hard-earned money enjoying. Seltzer claimed to have read an article that stated that well over 90% of Americans roller skated at some point in their lives, but he also drew inspiration from previously held roller marathons, skating races, popular 6-day bicycle races, walkathons, and danceathons to create what he dubbed the Transcontinental Roller Derby (TRD).[ii]

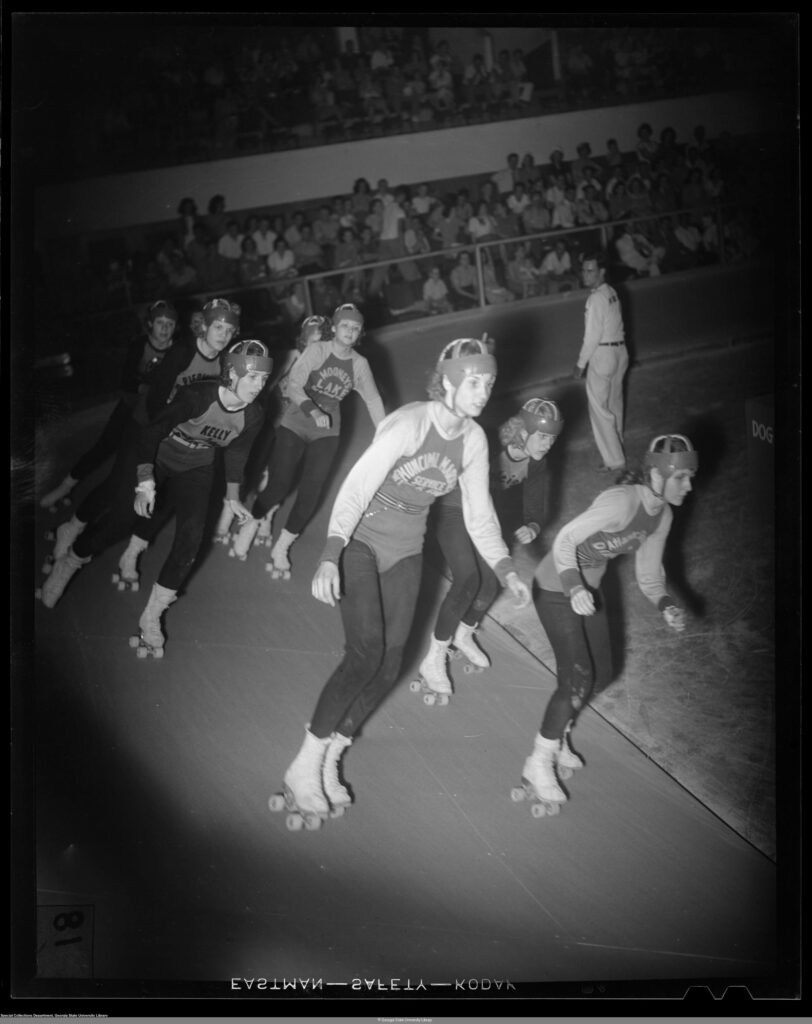

The first Transcontinental Roller Derby was held at the air-conditioned Chicago Coliseum on August 14, 1935, in front of 20,000 enthused fans. Here’s how it worked: ten co-ed pairs of skaters were competing against each other to, in essence, skate approximately 3,000 miles across the country (the distance could vary). One of each pair of skaters had to be skating on the track at all times the roller derby was open, which often was 6-12 hours a day. The women generally skated against the women for a particular interval and then men against the men. Their progress was tracked through a giant map of the United States featuring a transcontinental route, for instance, from Indianapolis to Los Angeles: According to Roller Derby: The History of an American Sport, “small lights on the map were lit as skaters advanced along the replicated path, marking their distance and mileage as they progressed city by city.”[iii]

The first skating duo to complete the 3,000 mile journey won the roller derby. Corrisse Martin and Benjamin McKay won the first TRD in Chicago. Roller Derby clearly a success, Seltzer took his spectacle on the road.[iv]

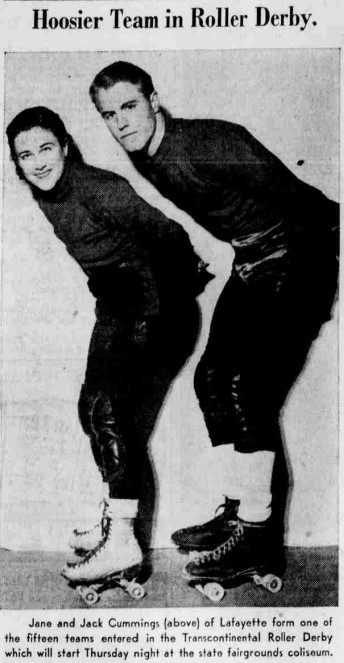

For the next couple of years, the TRD barnstormed the country, hosting Roller Derbies in venues across the nation. However, the business side of the Roller Derby operated out of Seltzer’s offices in Gary, Indiana.[v] Despite the ties to northern Indiana, the TRD did not skate in Indiana until the spring of 1937 when it rolled into Indianapolis. By then, Indy fans were eager to greet the sport and its skaters. According to an Indianapolis Star headline a week before the derby began, “Thrilling ‘jams’ await Roller Derby spectators” at the Coliseum at the state fairgrounds.[vi] Only one local Indianapolis resident participated in the first Hoosier Roller Derby: Tom Whitney. He was a veteran of the sport, however. Jane and Jack Cummings of Lafayette, a husband and wife team, joined the fray, and Gene Vizena, of East Gary, was also among the skating teams in that first competition in Indy.[vii]

The TRD would return to Indianapolis for a second stint in late September to mid-October 1937, again held at the Coliseum.[viii] Five thousand fans showed up to watch the competition on October 6, 1937, where they apparently discovered, “it was possible to yell louder than a combination of sirens and bells.”[ix] The fans loved it, but the newspapers weren’t exactly sure what to make of it. As one Star reporter wrote, “The curtain rolled up on the roller derby last night and if you will bear with the roller derby reporter while he unravels his neck and focuses his eyes he will try to tell you about this dizzy occupation.”[x]

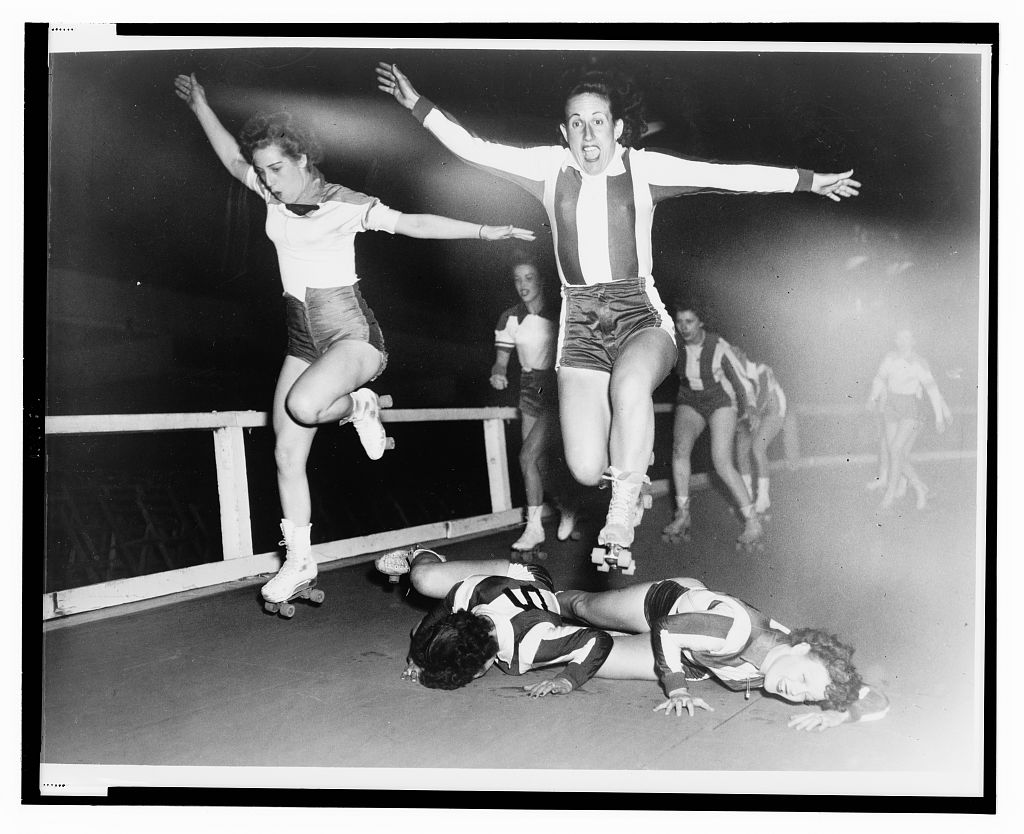

But major changes were a-coming to the Roller Derby late in 1937 that would dramatically alter the competition, propel it into the limelight, and eventually make people question its legitimacy. The rules prior to late December 1937 prevented skaters from any physical contact with each other as they completed the marathon-style endurance race. This had become a frustrating facet of the race for larger skaters who were frequently outmaneuvered by the smaller and quicker skaters that easily lapped them. At a series held in the Miami, Florida area late in the year, a group of skaters let their frustrations out on the track and “began pushing, shoving, and elbowing the speedsters, pinning them in the pack behind them . . . The referees ended the sprinting jams and started penalizing and fining the bigger skaters, eliciting loud boos and hisses from the excited crowd.”[xi] Leo Seltzer always paid close attention to crowd reactions and ordered the refs to allow the skaters to continue with contact, to much fanfare.

Later that night, Seltzer and famed essayist and playwright Damon Runyon, who was at the game and witnessed the enthusiastic crowd response, rewrote the rules over dinner to permanently allow contact. From that point forward, the game evolved away from a marathon-style race to a full contact team sport, albeit one with amped up dramatics, lots of hard-hitting, and frequently a fight or two.[xii]

Here’s how the new game worked: Five players of the same sex from each team started on the oval track together—two jammers (players that could score points) and three blockers. Once the referee blew his whistle, the ten skaters began skating counterclockwise around the track and then grouped together to form what was dubbed a “pack.” According to Roller Derby, once skaters formed the pack, “the jammers, who began in the back of the pack, attempted to work their way through the pack to break free from the blockers.”[xiii] The blockers had a more complicated job of playing simultaneous offense and defense—their mission was to prevent the opposing team’s jammers from breaking out of the pack while also helping their jammers break through the pack to then score points. Immediately after the first jammer broke free of the pack, a jam clock began: “this meant that the jammers had two minutes to lap the pack and attempt to score as many points as possible before the jam time ran out.”[xiv] Jammers scored points for every opponent they passed after breaking through the pack that first time.

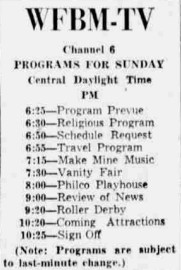

This newer version of Roller Derby really gained national prominence and coverage when it rooted itself in the New York City area with a lucrative ABC television network contract that telecast the event live every week for three years. From 1949-1952, the Roller Derby made its way into homes across the nation and became a staple of primetime TV. Various channels broadcast the sport for Hoosier viewers, ranging from the Indianapolis-based channel WFBM (Channel 6) to WGN out of Chicago (Channel 9) or WCPO Cincinnati (Channel 7).[xv] This provided a huge popularity boost to the sport, and fans loved watching the hard-hitting action of the male and female skaters competing together on a team. Indeed, it had higher viewership and ratings than other sporting events that were broadcast, such as boxing, wrestling, and college football, but there was a downside to this as well. The regular primetime programming without any sort of off-season led viewers, in part, to categorize the sport as entertainment television as opposed to a sporting event. This, along with the female skaters ready to battle it out on skates, endeared the sport to many while causing sports editors to thumb their noses at the Roller Derby.[xvi]

The Indianapolis Star coverage provides a great case study on the love-hate relationship with Roller Derby. Even prior to the TV exposure, the Indianapolis sports editors were leery of covering the Roller Derby as true sport, and often stories on the derby were intermixed among other sections of the paper—not in the “Sports, Financials, and Classifieds” section. As early as 1940, the Star sports editor explained why Roller Derby coverage wouldn’t appear on the sports pages: “When it came to the roller derby here we said, ‘Nay, nay’ for the sports pages—purely amusement. There was a squawk from the promoters, but the ‘front office’ backed us up in our contention.”[xvii]

Yet, Roller Derby was covered occasionally in the sports pages throughout the 1940s, but in 1954, the Star doubled down on their stance, despite continuing to provide coverage on the first Roller Derby in the city for years (on the sports page no less): “A mechanized morality play called the Roller Derby has dusted off an old wrestling script and moved dizzily into the Coliseum.”[xviii] The author allowed that “despite a journey that has no terminus, all on board seem to have fun. The crowd—made up of those who like to comment loudly on the performances of the athletes—exercises its vocal chords as strenuously as the athletes exercise their ideas of coed mayhem.”[xix] Still, he added an extra dig on the female skaters: “Girls skate against girls and boys against boys. But it’s quite difficult to determine when the sex of the competition changes off. If anything, the girls are the more nasty.”[xx]

Regardless, Hoosiers came out in droves to attend the Roller Derby whenever it came to Indiana. Roller Derbies were held at the Coliseum at the State Fairgrounds, at Victory Field, at Butler (now Hinkle) Fieldhouse in Indianapolis, and it even came to Fort Wayne in the spring of 1953.[xxi] According to the Angola Herald, “Fort Wayne [was] one of the smallest cities to ever play host to the Roller Derby teams. Most of the time the skaters are booked into large cities like New York, Philadelphia, Denver, Chicago, Milwaukee, San Francisco, and Los Angeles.”[xxii]

Over the decades, until the Seltzer Roller Derby folded in the mid-1970s, Hoosiers continued to grapple with their enjoyment of the game and their confusion over how to characterize it. Whether it was a “scripted morality play”[xxiii] or a “big league counterpart . . . to baseball, football, basketball and other sports,”[xxiv] Hoosiers loved the hard hits, big spills, and over-the-top action of the female and male skaters.

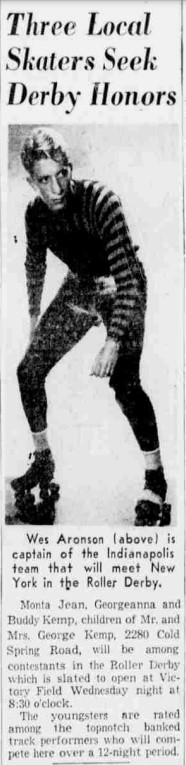

Stay tuned for another blog post focusing on Hoosiers starring in the Roller Derby, namely the Kemp family (3 Indianapolis siblings who took the sport by storm)!

Sources:

[i] “King and Aronson Lead Derby Field,” Indianapolis Star, May 1, 1937; Crowd of 8,376 At Roller Derby,” Indianapolis Star, May 2, 1937; “They Go ‘Round and ‘Round and Have The Darndest Time—At Roller Derby,” Indianapolis Star, September 29, 1937; “Derby ‘Menaced’ By Black Shirts,” Indianapolis Star, October 6, 1937; “Interest in Roller Derby Reaches New High; Hoosier Team Captain Returns,” Indianapolis Star, April 2, 1939; “Roller Derby Due At Victory Field,” Indianapolis Times, May 30, 1949; “Roller Derby Comes to Fort Wayne, Angola Herald, May 14, April 29, 1953; “Chiefs Beat Westerners, 35-34,” Indianapolis Star, October 29, 1954.

[ii] Michella M. Marino, Roller Derby: The History of An American Sport, (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2021),18-20; Hal Boyle, “Roller Derby Gives Women Something to Yell About,” Spokane Daily Chronicle, June 5, 1950; Leo Seltzer, quoted in Herb Michelson’s A Very Simple Game: The Story of Roller Derby, (Oakland, California: Occasional Publishing, 1971), 7; Jerry Seltzer, interview by author, June 17, 2011, Sonoma, California, digital audio recording, Michella Marino Oral History Collection, W.E.B. DuBois, University of Massachusetts Amherst.

[iii] Marino, 20; Bob Stranahan, “Thrilling ‘Jams’ Await Roller Derby Spectators,” Indianapolis Star, April 11, 1937.

[iv] Marino, 18-22.

[v] “Incorporations,” Indianapolis Star, September 18, 1935; “Kaplan Says His Arrest was Outrage,” The Times (Hammond, Indiana), November 24, 1937; Marino, 22-23.

[vi] Bob Stranahan, “Thrilling ‘Jams’…”; Bob Stranahan, “Skaters Practice at Coliseum Oval For Start of Roller Derby Tonight,” Indianapolis Star, April 15, 1937.

[vii] “Hoosier Team in Roller Derby,” Indianapolis Star, April 13, 1937; “Ten Roller Derby Teams Announced,” Indianapolis Star, April 14, 1937.

[viii] “Fall Roller Derby To Start Sept. 28,” Indianapolis Star, September 17, 1937; “Thirty in Derby Starting Tuesday,” Indianapolis Star, September 21, 1937; “They Go ‘Round and ‘Round and Have The Darndest Time—At Roller Derby,” Indianapolis Star, September 29, 1937;

[ix] “Derby ‘Menaced’ By Black Shirts,” Indianapolis Star, October 6, 1937.

[x] “They Go ‘Round and ‘Round and Have the Darndest Time—At Roller Derby,” Indianapolis Star, September 29, 1937.

[xi] Marino, 30.

[xii] Marino, 30-32.

[xiii] Marino, 30.

[xiv] Marino, 30.

[xv] “WFBM-TV Ch. 6 Programs for Friday,” Indianapolis Star, June 10, 1949; “Thursday TV, April 26, 1951,” Indianapolis Star, April 21, 1951; “WGN-TV Chicago (Channel 9),” Indianapolis Star, November 11, 1951; “Your Radio and Television Programs for Saturday,” Indianapolis Star, February 2, 1952 “Your Radio and Television Programs for Saturday,” Indianapolis Star, March 1, 1952.

[xvi] Marino, 38, 128-130

[xvii] W. Blaine Patton, “Playing the Field of Sports,” Indianapolis Star, February 8, 1940; Marino, 39.

[xviii] Frank Anderson, “Mayhem on Skates: Roller Derby Squads Follow Wrestling Cue,” Indianapolis Star, Sun. Oct. 31, 1954.

[xix] Anderson.

[xx] Anderson.

[xxi] “Ten Roller Derby Teams Announced,” Indianapolis Star, April 14, 1937; Bob Stranahan, “Skaters Practice at Coliseum Oval For Start of Roller Derby Tonight,” Indianapolis Star, April 15, 1937; “Interest in Roller Derby Reaches New High; Hoosier Team Captain Returns,” Indianapolis Star, April 2, 1939; “Field of 37 Set For Roller Derby,” Indianapolis Star, June 1, 1949; “Indianapolis Cops Lead in Roller Derby,” Indianapolis Star, June 2, 1949; “Roller Derby Comes to Fort Wayne May 14,” Angola Herald, Wed. April 29, 1953.

[xxii] “Roller Derby Comes to Fort Wayne May 14,” Angola Herald, Wed. April 29, 1953.

[xxiii] Anderson.

[xxiv] “Roller Derby Due At Victory Field.”