“Harry is a fine boy, he never told me a lie in his life,” Lena Pierpont proclaimed about her son, “Handsome Harry” Pierpont, who was considered the brains of the John Dillinger gang.[1] Like many families, the Pierponts rallied around their son in times of trouble. The extent to which they defended Harry demonstrated both the depths of parental love and the pitfalls of willful ignorance. Harry’s troubles centered on the frenzied period between September 1933 and July 1934, when the Dillinger gang became America’s most wanted criminals for a crime spree that impacted Indiana communities big and small.

While Dillinger became the FBI’s very first “Public Enemy Number 1,”[2] 32-year-old Harry Pierpont was often credited with being the architect of the Dillinger gang’s crimes, and the mentor who helped make Dillinger a skilled criminal.[3] Born in Muncie in 1902, Pierpont had amassed a lengthy criminal history long before meeting up with Dillinger. Pierpont was linked to a series of 1920s bank and store robberies across the state, including in Greencastle, Marion, Lebanon, Noblesville, Upland, New Harmony, and Kokomo, prior to landing in the Indiana State Prison at Michigan City – where he befriended and mentored Dillinger.

Pierpont’s criminal sophistication, however, had not spared him from arrest. By July 1934, he was arrested and awaited execution in Ohio for the murder of Lima County Sheriff Jesse Sarber. The sheriff had been killed in October 1933 as gangsters broke Dillinger out of the county jail. Pierpont’s mother, Lena, and father, J. Gilbert, instinctively believed in their son’s innocence and grew resentful over the “persecution” they said they endured from authorities after they had relocated from Ohio to Goshen, Indiana in April 1934. Pierpont’s beleaguered parents had come to the Hoosier city to try and “make an honest living in a respectable business.”[4]

By mid-July, with Dillinger still at large (although only days away from being slain by federal officers in Chicago), the Pierponts were under constant surveillance in an all-out effort to locate Dillinger. They had rented a “barbeque and beer parlor” on what was then called State Road 2 (now U.S. 33 West). Known as the “Cozy Corner Lunch” spot, the roadhouse was a half mile northwest of the famous A.E. Kunderd gladiola farm just outside the Goshen city limits.[5] Conducting what she called her first “free will interview” given to a journalist, Lena told the The Goshen News Times & Democrat, “I am going to try and open this place and run a legitimate business as soon as these men stop trailing us. Mr. Pierpont (her husband) is ill and unable to work, so all we want is to earn an honest living.”[6]

The Goshen News Times & Democrat reported that the Pierponts had rented the barbeque stand on an one-year lease offered by a couple identified as Mr. and Mrs. Rodney Hill. Although summer was nearly half over, the Pierponts had not opened for the year because a requisite beer license was still pending. The Pierponts believed this was held up by local officials facing pressure from federal authorities. Lena bitterly explained that the couple had sold all of their farm goods in Ohio in order to open the Goshen business.

“We should not be persecuted,” Lena explained. “We’re simply unfortunate. The government should call off its detectives and allow us to live as other good American citizens.” She pointed at a car parked about a quarter mile away and said, “See that car down the road? They’re always watching us.” She alleged that “Every minute for 24 hours a day we’re shadowed. They think we know (John) Dillinger and that he may come here. We don’t know him and we don’t want to.”[7] She insisted that her son was hiding in the attic of her home on the night the Ohio sheriff was killed, and while he was a fugitive escapee from the Indiana State Prison at the time, he was no murderer.[8]

Lena suggested that if she and Gilbert did know Dillinger maybe “we could get a deposition from him to the effect that our son, Harry, did not kill Sheriff Jess Sarber at Lima, Ohio.” Harry had assured her that Dillinger would clear him of the murder “and name the real slayer,” thus saving her son from the electric chair in Ohio.[9] The Indianapolis Times reported in September, Lena successfully arranged to meet with him in Chicago. According to her account, when asked who freed him from the Lima jail, Dillinger said “‘I’ll tell you who turned me out. Homer Van Meter is the man who fired the shot that killed Sarber and Tommy Carroll and George McGinnis are the men who were in the Lima jail and turned me out.'”[10]

Although used to letting his wife serve as family spokesperson, Gilbert Pierpont told an enterprising reporter from The Goshen News-Times & Democrat, “Harry (Pierpont) will not die for the murder of Sheriff Sarber. We are looking for a reversal of the Lima verdict by the Ohio Supreme Court. If not, the case will go to the United States Supreme Court.”[11] Harry’s angry and reportedly ill father said he didn’t like talking to reporters “because of so many false statements they have made about my son.” Contrasting her ailing husband, Lena “was jovial during the interview” and “jokingly remarked that the press would have it all wrong” when writing about her son.[12]

State and federal law enforcement officials were quick to impeach the Pierponts. Captain Matt Leach, who headed the effort of the Indiana State Police to bring the marauding gang to justice, actually identified Pierpont as “the brains” of the Dillinger gang. It was Pierpont, Leach said, who came up with the idea of springing Dillinger from the county jail in Lima by posing as Indiana police officers. When Sheriff Sarber demanded to see their credentials, Pierpont reportedly said, “Here’s our credentials,” and fired multiple shots into the lawman, killing him instantly.[13]

It was a short-lived, but “productive” period of freedom for thirty-one-year-old Dillinger after being sprung from the Lima jail. During this stint, he led his gang in a bold April 12, 1934 raid on the Warsaw Police Department, where they seized a cache of guns. The gang also conducted a deadly robbery of the Merchants National Bank in downtown South Bend on June 30, killing a police officer and injuring four others in a brazen sidewalk shootout. Federal agents put a stop to the spree when they gunned down Dillinger on the streets of Chicago on July 22, just nine months after the Pierpont-led escape from the Ohio jail.

While Dillinger met his “death sentence” on a Chicago street, Pierpont remained on Ohio’s death row for the murder of Sheriff Sarber. Lena said she and her husband would continue to make the journey of more than 200 miles from Goshen, Indiana to Columbus, Ohio, “every weekend” to see their son. “We will continue to do this as long as we have any money,” she said.[14] Lena also declared she would continue to challenge state and federal authorities for their alleged harassment of her family. She had reportedly talked to an Elkhart attorney about bringing suit against state and federal authorities.

“We are unfortunate that our son is in prison under sentence of death,” Lena said, adding “No other members of our family have a criminal record. We should not be persecuted. They tell us that these men, who are constantly nearby in parked automobiles ready to follow us at any time we may leave, are federal government men.”[15] Lena’s claim that her son Harry was the only member of her family who had run afoul of the law was not accurate. The Pierponts’ younger son, Fred, 27, and Lena herself, were both arrested and held on illegal possession of weapons charges and vagrancy in Terre Haute in December 1933. A car driven by Lena on the day she was arrested contained almost $500 in cash and a sawed-off shotgun.

To publicize her claims of harassment, a day after granting an exclusive interview to The Goshen News Times & Democrat (picked up by the Associated Press and reported by newspapers across the nation), Lena marched into the Elkhart County Courthouse at Goshen, demanding that she be granted her long-delayed beer license and that an “order of restraint” be placed against detectives following them.[16] Despite his family’s attempts to win over “the court of public opinion,” as summer gave way to fall in 1934, Harry’s appeals to the Ohio Supreme Court were coming to no end other than delaying his execution. Surprisingly, in late September, Pierpont and fellow Dillinger gang member, Charles Makley, staged a spectacular, yet unsuccessful escape attempt from the Ohio Penitentiary. Fashioning realistic-looking handguns made of soap (and blackened with shoe polish), Pierpont and Makley were immediately “outgunned” by prison guards, who killed Makley and critically wounded Pierpont in a shootout.[17]

By October, Pierpont could no longer escape his fate. As one reporter noted, Pierpont “whose trigger finger started the John Dillinger gang on its short but violent career of crime that blighted everything it touched, must die in the electric chair at the Ohio Penitentiary.” Prison officials reported “the doomed man has reconciled himself to death and embraced his former faith, the Roman Catholic religion.”[18]

Sullen and weakened by the gunshot wounds sustained during his failed prison escape, Pierpont strongly contrasted with “the braggart who once boasted he would kill every cop on sight.” Now, jailers said, Pierpont wished out loud that he too had been fatally wounded in the prison shootout.[19] “Pierpont’s mother, Lena, by this time living near Goshen, Indiana, and his sweetheart, Mrs. Mary Kinder, an Indianapolis gang ‘moll,’ are remaining true to the fallen gangster to the last,” one newspaper account told. Kinder, whom reporters were quick to point out was previously married, “even went to Columbus recently[,] determined to marry Harry in prison before he dies.”[20]

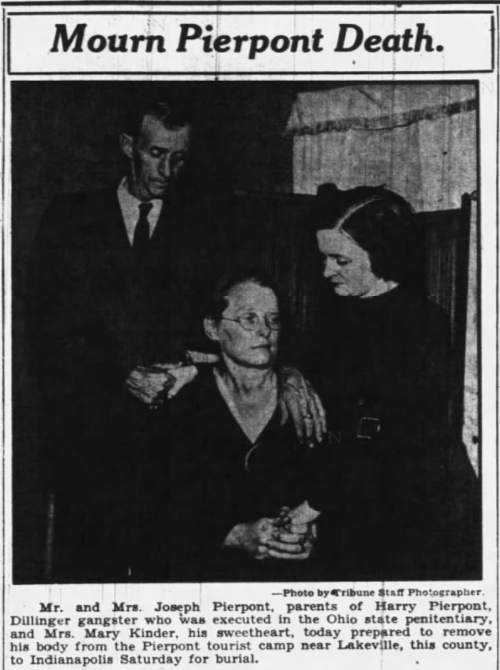

On October 17, 1934, the “fair-haired brains of the dissolved Dillinger mob” was executed. The Associated Press noted, “Quietly, unaided and with the ghost of a smile on his lips, the 32-year-old killer sat down to death in the gaunt wooden chair within the high stockade of the prison guarded in unprecedented fashion.”[21] Reporters who witnessed the execution said Pierpont “was not asked for any ‘last word,’ and he volunteered none. He just sat down with a rueful smile, closed his eyes, strained the muscles of his lanky, six-foot-two frame, as the current struck, clenched one fist – and that was all.”[22] A national wire photo showed Kinder comforting Lena and Gilbert at their new home along U.S. 31 in Lakeville in St. Joseph County, where they had moved after their failed attempt to start a roadhouse near Goshen.

A funeral was conducted for Harry inside the Pierponts’ home, led by a priest from the Sacred Heart Catholic Church of Lakeville. The services were held an hour earlier than was announced to keep reporters away. Harry Pierpont had told Ohio prison officials that he desired a “simple, but lavish funeral” and wanted his remains be released to his parents in Indiana.[23] The South Bend Tribune reported, “His casket was adorned only by a small wreath of artificial flowers, and lay grotesquely surrounded by canned goods and automobile accessories in his parent’s home store.”[24] Harry was eventually buried at the Holy Cross and St. Joseph Cemetery in Indianapolis.

Lena Pierpont would appear in the news one more time for her resilience. In the summer of 1937, Lakeville town authorities took court action to rid the village of “a band of roving coppersmiths” who had settled at Lena’s White City Inn. Surely she refused to oust them because she needed the income in the lean Depression years, but perhaps she also related to those on the fringes of society, trying their best to survive.[25]

The Pierponts suffered another tragedy when Harry’s younger brother, Fred, died in March 1940 at the age of 33 from injuries suffered in a car crash near South Bend. Perhaps being forced to hone the art of resilience due to the upheaval wrought by Harry helped them survive this second blow. Lena died in her Lakeville home on October 21, 1958 at the age of 78. Her long-suffering husband Gilbert, died three years later also at Lakeville at the age of 80. They were buried alongside their infamous son in Indianapolis.[26]

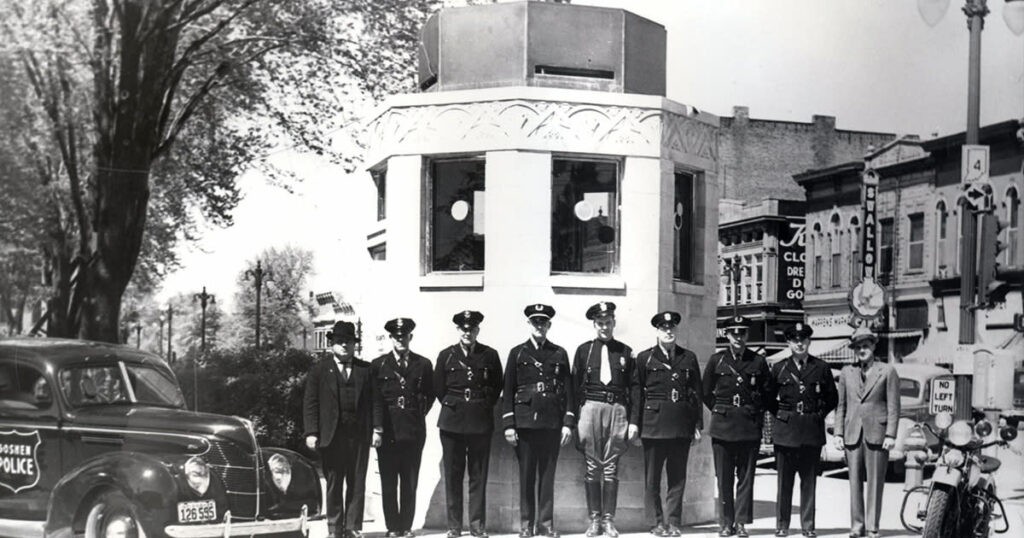

* Interestingly, the Goshen connection to the Dillinger gang, beyond the Pierponts’ battles there, is forever enshrined in the city’s limestone police booth opened in 1939. The impressive octagon structure sits on the corner of the Elkhart County Courthouse square, opposite Goshen’s two largest banks. Complete with bulletproof glass (donated by two of the city’s banks), the booth (partially funded by Works Progress Administration dollars) was never called into duty as Goshen’s banks escaped being robbed.

Sources:

*Primary documents were accessed via Newspapers.com, the Goshen Public Library, and the Goshen Historical Society.

[1] Associated Press, July 12, 1934.

[2] Andrew E. Stoner “John H. Dillinger, Jr.” in Linda C. Gugin and James E. St. Clair, eds., Indiana’s 200: The People Who Shaped the Hoosier State (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press, 2015), 96.

[3] Patrick Sauer, “Harry Pierpont: John Dillinger’s Mentor” in Julia Rothman and Matt Lamothe, eds., The Who, the What, the When: Sixty-Five Artists Illustrate the Secret Sidekicks of History, (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, LLC., 2014), 42.

[4] Goshen News Times & Democrat, July 12, 1934.

[5] Goshen News Times & Democrat, July 19, 1934.

[6] Goshen News Times & Democrat, July 12, 1934.

[7] Goshen News-Times & Democrat, July 12, 1934.

[8] United Press, July 13, 1934.

[9] Associated Press, September 23, 1934.

[10] Indianapolis Star, July 13, 1934.

[11] Goshen News-Times & Democrat, July 12, 1934.

[12] Goshen News-Times & Democrat, July 12, 1934.

[13] Paul Simpson, The Mammoth Book of Prison Breaks: True Stories of Incredible Escapes (London Constable & Robinson, LTD., 2013).

[14] Goshen News-Times & Democrat, July 12, 1934.

[15] Associated Press, December 14, 1933.; Goshen News-Times & Democrat, July 12, 1934.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Associated Press, September 22, 1934.

[18] Massillon (Ohio) Evening Independent, October 4, 1934.

[19] Massillon (Ohio) Evening Independent, October 4, 1934.

[20] Massillon (Ohio) Evening Independent, October 4, 1934.

[21] Associated Press, October 17, 1934.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Indianapolis Star, October 19, 1934.

[24] South Bend Tribune, October 18, 1934.

[25] United Press, June 8, 1937.

[26] Muncie Evening Press, October 22, 1958.; Muncie Star-Press, October 4, 1961.; Associated Press, March 6, 1940.

![Midwest Railroads Map, circa 1860, showing the Madison and Indianapolis [M&I], Terre Haute and Richmond [TH&R], and component roads of the Bee Line: Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati [CC&C]; Bellefontaine and Indiana [B&I]; Indianapolis and Bellefontaine](http://blog.history.in.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Midwest-Railroads-Map-c1860.png)

![Railroads west from Indiana, including the Terre Haute and Richmond [TH&R], Ohio and Mississippi [O&M], Mississippi and Atlantic [M&A], and St. Louis, Alton and Terre Haute [StLA&TH]](http://blog.history.in.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Railroads-West.png)

![image of The Madison and Indianapolis Railroad [M&I] and involved roads: the Peru and Indianapolis Railroad [P&I], extending north from Indianapolis, and the Mississippi and Atlantic Railroad [M&A], extending west to St. Louis. Terre Haute and Richmond [TH&R]](http://blog.history.in.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/MI.png)