Indianapolis author and satirist Kurt Vonnegut Jr. would have turned 95 on November 11, 2017, just five years shy of his centennial. Few people on this earth have had a birthday of such significance; a World War veteran himself, Kurt was born on the 4th anniversary of Armistice Day. The writer who was once described as “a satirist with a heart, a moralist with a whoopee cushion,” was born into an incredibly prominent Indianapolis family. His great-grandfather, Clemens Vonnegut, founded Vonnegut Hardware Store and was a major civic leader. His grandfather and father were both prominent architects, responsible for the former All Souls Unitarian Church on Alabama Street, the Athenaeum, the clock at the corner of Washington and Meridian, and many more Indianapolis landmarks. (Visit the Vonnegut Library and pick up a copy of our Vonnegut Walking Tour pamphlets).

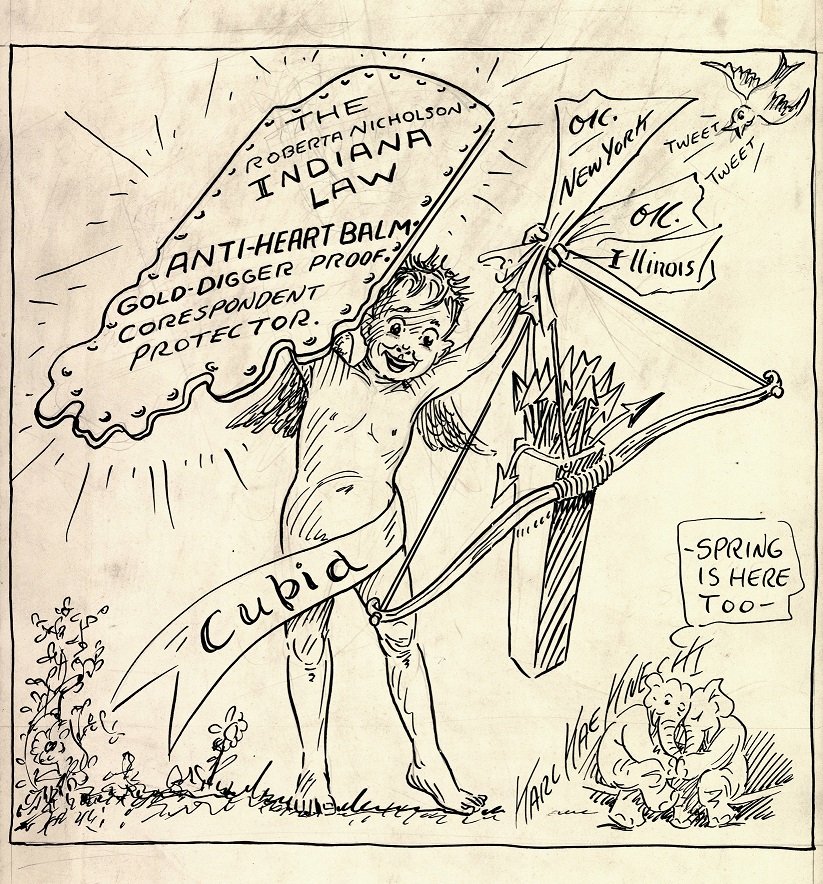

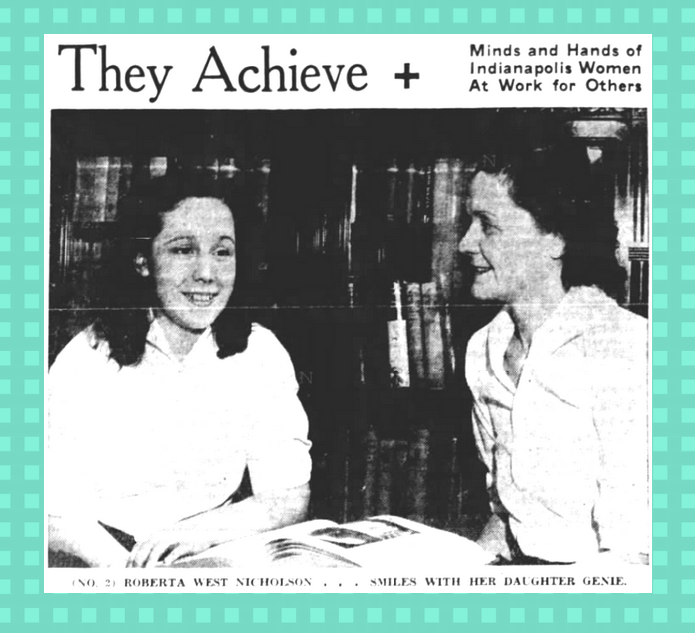

Kurt was raised in luxury at 4401 North Illinois Street, a house designed by his father Kurt Vonnegut Sr. in 1922. According to Indianapolis Monthly, “original details like a stained-glass window with the initials ‘KV’ and Rookwood tile in the dining room” still remain. Kurt Jr. spent summer vacations at Lake Maxinkuckee, located in Culver, Marshall County. The Vonnegut family owned a cottage at the lake, where, according to the Culver-Union Township Library, Hoosier author Meredith Nicholson conceived of the idea for his The House of a Thousand Candles.

Reportedly, Kurt noted in an Architectural Digest article:

“…I made my first mental maps of the world, when I was a little child in the summertime, on the shores of Lake Maxinkuckee, which is in northern Indiana, halfway between Chicago and Indianapolis, where we lived in the wintertime. Maxinkuckee is five miles long and two and a half miles across at its widest. Its shores are a closed loop. No matter where I was on its circumference, all I had to do was keep walking in one direction to find my way home again. What a confident Marco Polo I could be when setting out for a day’s adventures!”

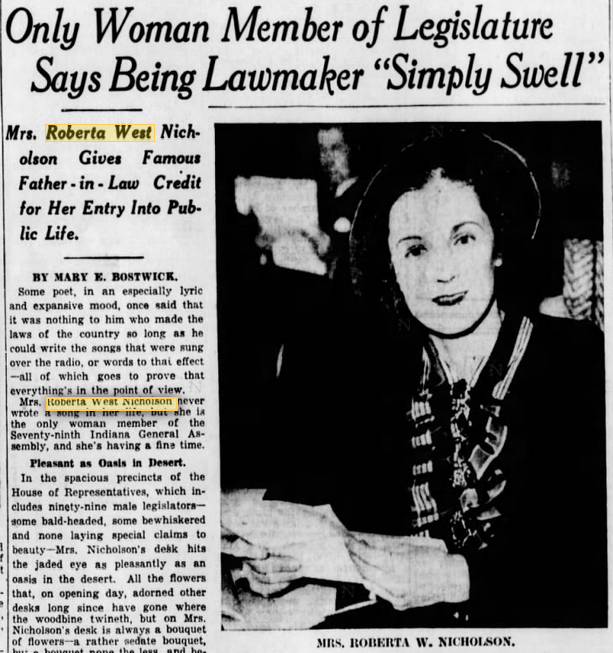

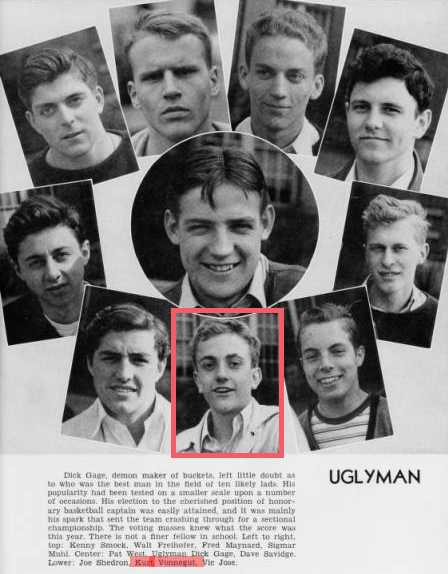

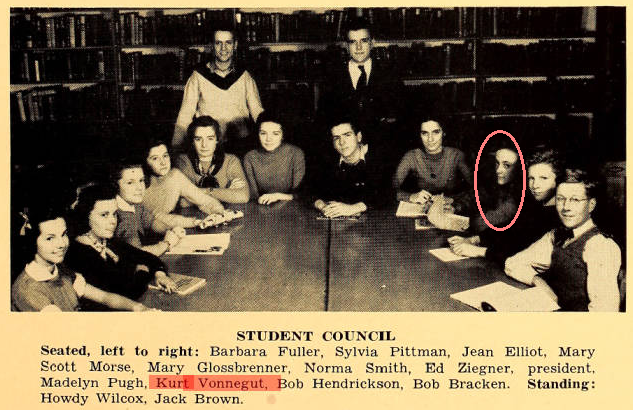

Kurt’s parents lost a significant amount of money during the Great Depression, resulting in Kurt leaving his private gradeschool and attending James Whitcomb Riley School, named after the Hoosier poet. He received an excellent education at Shortridge High School in Indianapolis. Here, he badly played clarinet in the jazz band, served on the school newspaper and, upon graduation, was offered a job with the Indianapolis Times. His father and brother talked him out of accepting it, saying he would never make a living as a writer.

According to the Indiana Historical Society, “Along with instilling Vonnegut with a strong sense of ideals and pacifism, his time in Indianapolis’s schools started him on the path to a writing career. . . . His duties with the newspaper, then one of the few daily high school newspapers in the country, offered Vonnegut a unique opportunity to write for a large audience – his fellow students. It was an experience he described as being ‘fun and easy.’” Kurt noted, “‘that I could write better than a lot of other people. Each person has something he can do easily and can’t imagine why everybody else has so much trouble doing it.’ In his case that something was writing.” He also admired Indianapolis’s system of free libraries, many established by business magnate Andrew Carnegie.

Kurt ended up attending five total colleges, receiving zero degrees for the majority of his life, and ending up in World War II. It’s no coincidence that he spent his life writing about the unintended consequences of good intentions! Captured at the Battle of the Bulge and taken to Dresden, he survived the bombing that killed (by modern day estimates) 25,000 people, while held in a meat locker called Slaughterhouse-Five. He survived the war, though stricken with combat trauma, and returned here to marry his school sweetheart Jane Cox. After they moved to Chicago, he would not return to Indianapolis to live, although he visited with some frequency. Suffice it to say, the Hoosier city was where he learned the arts and humanities and loved his family dearly. It was a place of tragedy as well, as his family had lost their wealth and his mother committed suicide on Mother’s Day Eve in 1944. He had to move on.

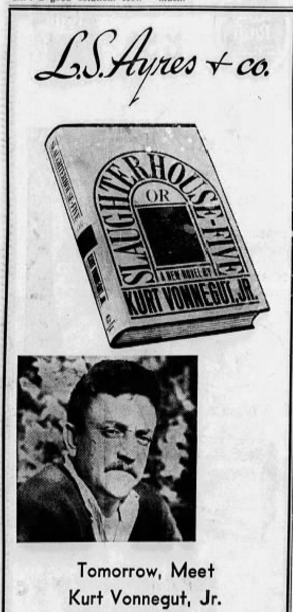

Kurt spent the next twenty-four years writing what many would call one of the most significant novels of the 20th century, Slaughterhouse-Five. The semi-autobiographical satire of his experiences during World War II was released at the height of the anti-Vietnam War movement. With this novel, Kurt became quite famous, at the age of 46. His books, short stories, essays, and artwork have provided comfort to those who have grown weary of a world of war and poverty.

Kurt’s work affected me profoundly, first reading Breakfast of Champions as an undergraduate. I continued to read Kurt Vonnegut constantly, throughout life’s trials and triumphs, always finding very coherent and succinct sentences that seemed to address exactly how I was feeling about the world at the moment. As an individual growing up in Indiana, I loved how my home state featured as a character in nearly all of his work, from the beautiful, heart wrenching final scene in the novel The Sirens of Titan, to the hilarious airplane conversation in Cat’s Cradle, to the economically downtrodden fictional town of Rosewater, Indiana in God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater, to the planet Tralfamadore from Slaughterhouse-Five (I personally think he took it from Trafalgar, Indiana. While I have no proof, his father did spent the last two years of his life living in Brown County, not very far away)!

So it was the honor of a lifetime in 2011 to join the staff of the Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library in downtown Indianapolis. Throughout the years we have tirelessly drawn attention to issues Kurt Vonnegut cared about, the struggle against censorship, the war on poverty, the desire to live in a more peaceful and humane world, campaigning to help veterans heal from the wounds of war through the arts and humanities. These pursuits are inspired by a man who wrote about these issues for eighty-four years, until a fall outside his Manhattan brownstone “scrambled his precious egg,” as his son Mark Vonnegut described it. To me, Kurt Vonnegut is not gone, he is alive in the minds of our visitors, who themselves all have interesting stories about how they came to the work of Mr. Vonnegut, or are simply curious to learn more. Time being flexible is an idea Kurt himself seemed to espouse in his novel Slaughterhouse-Five:

The most important thing I learned on Tralfamadore was that when a person dies he only appears to die. He is still very much alive in the past, so it is very silly for people to cry at his funeral. All moments, past, present, and future, always have existed, always will exist. The Tralfamadorians can look at all the different moments just the way we can look at a stretch of the Rocky Mountains, for instance. They can see how permanent all the moments are, and they can look at any moment that interests them. It is just an illusion we have here on Earth that one moment follows another one, like beads on a string, and that once a moment is gone it is gone forever.

In 2017, the Year of Vonnegut, we focused on the issue of Common Decency. Our 2018 programming will focus on the theme Lonesome No More, which we took from Kurt’s criminally underrated 1976 novel Slapstick, in which he runs for President under that slogan, in attempt to defeat the disease of loneliness. We’re going to give it our best shot, I humbly request that you join us!

Edited and co-researched by Nicole Poletika, Research & Digital Content Editor at the Indiana Historical Bureau.