Professor Rasul Mowatt contended that memory is recollection, reflection, retention, recall, and, perhaps most importantly, a process at this weekend’s Workshop on Antiracism & Community-Based Memory Work. We were honored to be invited to the workshop—sponsored by IU’s “Unmasked: The 1935 Anti-Lynching Exhibits and Community Remembrance”—and found it particularly helpful in thinking about how we present forthcoming markers about racial violence to the public, such as that commemorating the lynching of John Tucker in Indianapolis. It also gave us ideas in ongoing pursuit of markers for the 1930 Marion lynching of Tom Shipp and Abe Smith, as well as Flossie Bailey, who tried to stop their lynching. It is impossible to summarize the many insights we came away with, but we’ll highlight a few.

Across the panels, speakers touched on the emotional toll of doing this work. In fact, Sylvester Edwards, of Facing Injustice and Terre Haute’s NAACP branch, described the Present Traumatic Stress Disorder he and other Black Americans experience in reckoning with this history. Edwards, the great-nephew of prolific activist Fannie Lou Hamer, helped lead efforts to install a local marker commemorating the 1901 lynching of George Ward in Terre Haute. Accused of murdering a white woman, a mob pulled Ward from the local jail, lynched him, and burned his body along the Wabash River. Between 1,000 and 3,000 spectators witnessed the lynching, as they picnicked. Many took the remains of Ward’s body as a “souvenir.” The atrocity caused Terre Haute’s Black community to flee.

The lynching was quickly buried in the city’s collective memory and was not brought to light until Ward’s great-grandson, Terry Ward, approached the Equal Justice Initiative about doing a soil collection at the lynching site in 2020. He also worked with Edwards and the local NAACP to commemorate the lynching with a local historical marker. The marker dedication ceremony, which drew about 350 people, served as a celebration of life for the man who never had a burial or funeral. Edwards stated that these memorialization efforts helped the Ward family shed the shame association with the lynching. Terry told WFYI that the marker served as:

‘a source of strength, I think, for those of us who look back on our history and realize that we are not what they accused our ancestors of being. That we have an opportunity based on what our ancestors experienced to try to raise ourselves up above that.’

Edwards ended his talk at the workshop on a hopeful note. He was pleasantly surprised to see a number of white students win EJI awards for submitting essays about the lynching.

The work of Marquette University history professor Dr. Robert Smith can be tied back to another lynching in Indiana, that of teenagers Tom Shipp and Abe Smith in 1930. Shipp, Smith, and James Cameron were held in the Marion jail for the murder of Claude Deeter and rape of Mary Ball. Before the young men could stand trial, a mob comprised of white residents tore the young men from their cells, brutally beat and mutilated them before hanging Shipp and Smith from a tree on the courthouse lawn. Cameron narrowly escaped the fate of his friends. Out of fear of escalating violence, about 200 Black residents fled Marion for Weaver, a historic Black community in Grant County. The mob intended to send a message to the Black community that they were at the mercy of white residents.

How did the victims’ friends and family process their trauma and sorrow? For James Cameron, survivor of the lynching, it meant confronting local racism through threat of lawsuits and, later, by educating the nation about racial injustice by founding America’s Black Holocaust Museum (ABHM) in Milwaukee in 1988. The site closed in 2008 due, in part, to the recession and operated virtually until 2022. Working with James’s son, Virgil, and local volunteers, Dr. Smith helped open the museum’s new site, which serves as a community center. At Saturday’s workshop, Dr. Smith implored scholars and professors to place more value on the knowledge and expertise of those outside of academia. He stated that a university’s objective should be to inspire dignity, and that scholars must be patient with the process of memorialization, as individuals’ timelines do not always correspond with university deadlines.

Panelist Benjamin Saulsberry, Public Engagement & Museum Education Director at the Emmett Till Interpretive Center, helped with “Emmett Till and Mamie Till-Mobley: Let the World See” exhibit at The Children’s Museum. His insights were especially relevant to our work, as he detailed how historical markers can return stories to the landscape when physical structures no longer remain. He discussed the sad reality of vandalism against markers that commemorate racial violence, something we are mindful about as we prepare to install the John Tucker lynching marker in the heart of Indianapolis. Saulsberry left us with this statement: racial brutality includes not just the act of violence itself, but the lack of accountability from institutions.

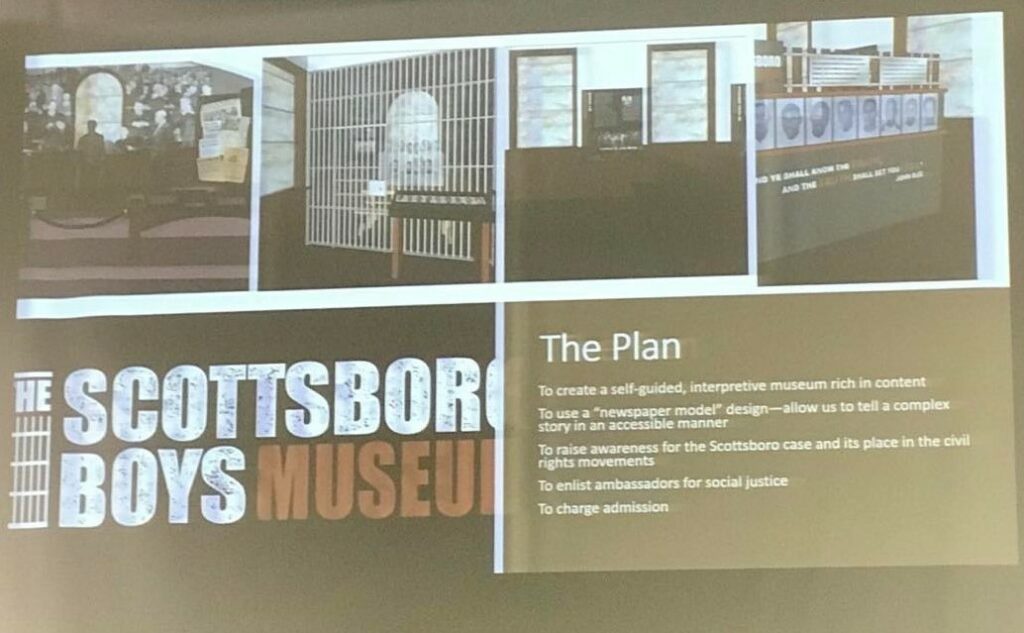

Thomas Reidy, of the Scottsboro Boys Museum, also highlighted institutional injustice. In 1931, nine Black teenagers in Scottsboro, Alabama were found guilty by an all-white jury of raping two white women—one of whom later admitted to fabricating the crime—while riding the Southern Railroad freight train in search of work. Despite no evidence, poor legal aid, and rushed trials, the Scottsboro boys were sentenced to death. This instance of legal injustice generated global outrage, and mass protests resulted in the US Supreme Court overturning the convictions. However, the boys had to endure a series of retrials and reconvictions. Most were convicted of rape and served prison sentences.

At Saturday’s workshop, Reidy spoke about the Scottsboro Boys Museum’s efforts to create social change through education. Sheila Washington founded the Scottsboro Boys Museum in Joyce Chapel in 2010. Through her and Reidy’s efforts, Gov. Robert Bentley signed the Scottsboro Boys Act into law in 2013. This law ensured that all nine boys—Haywood Patterson, Olen Montgomery, Clarence Norris, Willie Roberson, Andy Wright, Ozzie Powell, Eugene Williams, Charley Weems, and Roy Wright—received pardons. Washington told the Montgomery Advertiser that Gov. Bentley’s “decision will give them a final peace in their graves, wherever they are.” Reidy spoke to us about the museum’s ongoing efforts to use history to make more informed citizens. He highlighted the importance of getting into classrooms or bringing them to your institution, especially in light of recent legislation regarding history curriculum.

Although all of Saturday’s panelists were profoundly informative, we were especially inspired by intrepid Mount Vernon High School student Sophie Kloppenburg. After learning about the lynching of Daniel Harrison Sr., his sons John and Daniel Jr., Jim Good, William Chambers, Ed Warner, and Jeff Hopkins, she made it her mission to bring their story to the public. In 1878, white women accused the men of rape, and as the men awaited trial, a mob pulled some of them from jail, hanging them from a tree on the grounds of the Posey County courthouse. The remaining men were tracked down and murdered. Shocked that she had never heard this history before, Kloppenburg began the process of getting a local marker installed on the courthouse lawn.

She encountered resistance from some community members and the city council. However, the budding historian attended a council meeting and was able to convince its members to approve of the marker. She also worked with locals to install a bench near the marker, inscribed with the names of the victims. Kloppenburg’s memorialization efforts did not stop there. She was able to obtain a National Endowment for the Humanities grant to incorporate the 1878 lynching into local curriculum. In working on this project, Kloppenburg, who is biracial and had no relationship with her father, was able to get in touch with the local Black community and her identity as a Black person in ways she previously had not.

The workshop closed with a heart-wrenching performance of “Strange Fruit,” a poem based on Lawrence Beitler’s photograph of Shipp and Smith swinging from a tree in Marion. The performance of Mississippi activist and jazz singer Effie Burt encapsulated the workshop’s main theme: history is not just something to be learned, rather that it evokes emotion, impacts identity, and can change perspectives. We are so grateful to those who examine and commemorate this history for the sake of collective memory, at the expense of their own mental well-being. We left the workshop with the solemn understanding that we are stewards of history that is sacred. The ways in which we examine and share it has the potential to help communities find reconciliation. Based on the efforts of younger generations, there is reason to be hopeful that the past can spur meaningful change and perhaps even restorative justice.