* Sources included in the historical marker application, compiled by historian Leon Bates, were foundational to this blog post.

Long before the Great Migration, Black Americans sought to make a living and secure housing in Indianapolis. The life of John Tucker affords us the opportunity to study the experiences of free people of color living in the city, when it was simply an outpost of the Western frontier. Tucker’s life also represented the many obstacles they faced in the pursuit of unequivocal freedom. In researching a new historical marker about Tucker’s violent death, I sought to uncover as many details as I could about his life, work, family, and experiences as a human. Amongst scant documentation, I gleaned that he was a farmer, who raised two children with his wife in a house near the intersection of St. Clair and Delaware Streets. Prominent orator Rev. Henry Ward Beecher noted that Tucker was “very generally respected as a peaceable, industrious, worthy man.”[1] On Independence Day of 1845, his pursuit of a life of freedom was brutally ended by white violence. Tucker’s death forced his young children into a years-long legal battle over his property and undoubtedly perpetuated generational trauma. The lynching also made overt the indignities and threats Black settlers had quietly endured.

Tucker was born into enslavement in Kentucky around 1800. It is unclear how or when he was freed, but the Indiana State Sentinel reported in 1845 that he “many years ago honorably obtained freedom.”[2] By 1830, Tucker settled in Indianapolis, which resembled “‘an almost inaccessible village,'” lacking navigable waterways and roads. As Indianapolis’s Black population increased, so did discrimination against Black Americans.[3] The Indiana General Assembly passed laws requiring them to register with county authorities and pay a bond as guarantee of good behavior.[4] Black residents were also prohibited from voting, serving in the state militia, testifying in court cases against white persons, and their children were banned from attending public schools.

Despite living in a “free” state, Black settlers not only experienced systemic discrimination, but were marginalized by racial violence. City historian Ignatius Brown described Indianapolis in the 1830s:

The work on the National road . . . had attracted many men of bad character and habits to this point. These, banded together under a leader of great size and strength, were long known as ‘the chain gang,’ and kept the town in a half subjugated state. Assaults were often committed, citizens threatened and insulted, and petty outrages perpetrated.[5]

James Overall, a respected free person of color, land-owner, and trustee for the African Methodist Episcopal church, would become a target of this violence in 1836. David J. Leach, a white gang member, tried to break into Overall’s home, located on Washington Street, and threatened to kill his family.[6]

Overall shot Leach in self-defense. In this tense circumstance, prominent white allies of Overall came to his aid. Despite an 1831 Indiana law that barred black testimony against whites in court, Overall gained legal protection from further attack. In his official opinion, Judge William W. Wick affirmed Overall’s “natural” right to defend his family and property. Unfortunately, Judge Wick’s interpretation of the 1836 law did not affect any change in the actual law and African Americans in Indiana continued to be without legal recourse in cases where only black testimony was available against a white party.

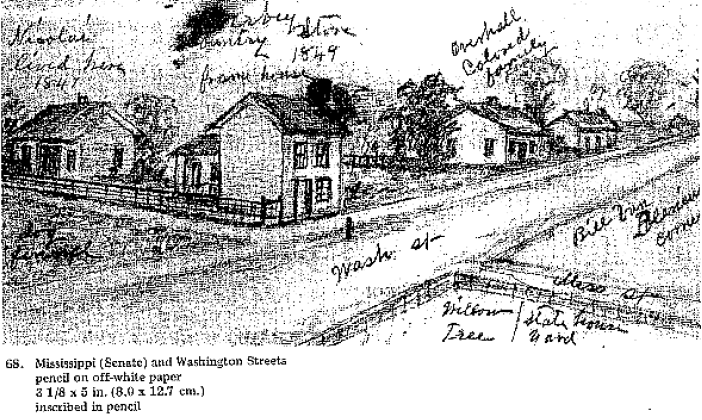

Overall’s home would again be linked to racial violence when Tucker’s body was transported to it for examination by a coroner.[7] The sequence of events resulting in Tucker’s death were generally corroborated by the testimony of approximately forty white witnesses at trial.[8] On the afternoon of July 4, 1845, Tucker was walking along Washington Street when inebriated white laborer Nicholas Wood physically assaulted him. Bewildered, and with few options for recourse because of his race, Tucker sought the intervention of city officials.[9] While Tucker headed to the Magistrate’s Office, Wood again struck him with a club. Tucker retreated up Illinois Street as Wood followed, now joined by saloon keeper William Ballenger and Edward Davis. Rev. Beecher reported that Tucker “defended himself with desperate determination” against the stones and brickbats hurled at him by the three men.[10] The “murderous affray” took place about 100 yards from Rev. Beecher’s church, and “greatly disturbed” the Independence Day celebration taking place that afternoon.[11]

A crowd surrounded Tucker on Illinois Street. Some gatherers tried to separate Tucker from his assaulters, while others encouraged the violence, chanting “kill the n****r!” Rev. Beecher reported that “the fight was at first scattering, and the mayor attempted to quell the rioters, as did several citizens,” but most “surprised at the suddenness and rapidity of the thing, stood irresolute or timid, having no courageous man among them to save the victim.”[12] Within minutes, John Tucker succumbed to his injuries near a gutter on Illinois Street. Although not the result of a hanging, his death is considered a lynching, as defined by the Equal Justice Initiative: “Lynchings were violent and public events designed to terrorize all Black people in order to re-establish white supremacy and suppress Black civil rights.”

Immediately after the lynching, Wood was brought before Mayor Levy, and “being rather uproarious with liquor, and the excitement considerable, the Mayor very properly committed the accused” to jail until the following day. Davis sustained severe injuries from Tucker’s attempts to defend himself, and had to recuperate at home before a court appearance was possible.[13] By the time Wood informed Mayor Levy about Ballenger’s involvement and a warrant was written for his arrest, Ballenger “had already secreted himself.”

Rev. Beecher described the general sentiment felt by Indianapolis’s citizens in the immediate aftermath of the tragedy. He wrote, “I never saw a community more mortified and indignant at an outrage than were the sober citizens of this. Some violent haters of the blacks, the refuse of the groceries [grocery gang to which Wood belonged], and a very few hair-brained young fellows indulged in inflammatory language.”[14] Similarly, the Indiana State Sentinel wrote a few days after the lynching, “It was a horrible spectacle; doubly horrible that it should have occurred on the 4th of July, a day which of all others should be consecrated to purposes far different from a display of angry and vindictive passion and brutality.”[15] Unwilling to intervene in Tucker’s lynching, many citizens donated money to hire attorneys O.H. Smith and James Morrison, who would aid the state in prosecuting Tucker’s assailants. Prominent abolitionist and businessman Calvin Fletcher spearheaded efforts to secure counsel, writing in his diary, “as a citizen I have done all I could to see that the state should have Justice.”[16]

The Indiana State Sentinel reported that “Much difficulty presented itself in obtaining a jury in consequence of the notoriety of the case.”[17] Despite this, Edward Davis’s trial began by mid-August and several witnesses provided detailed testimony, including Tucker’s employer, City Postmaster Samuel Henderson.[18] Expert witnesses like Dr. John Evans, who helped establish the Indiana Hospital for the Insane, explained the significance of Tucker’s injuries to jury members. The Sentinel noted on August 13, “The examination of the witnesses was very laborious and great vigilance and attention given to it. The Court House was crowded to overflowing during the tedious detail.”

Despite damning testimony regarding his involvement in Tucker’s death, the jury acquitted Davis.[19] This surprised many in the community because days later the jury, hearing much the same testimony, found Nicholas Wood guilty of Tucker’s murder.[20] The Sentinel speculated on the reasoning for the differing verdicts, noting Wood was found guilty because he “commenced the affray, and followed it up to its conclusion.” Convicted of manslaughter, Wood was sentenced to three years in state prison.[21] Although a seemingly short sentence, his conviction was a rarity in an era when Black Hoosiers could not legally testify in court.

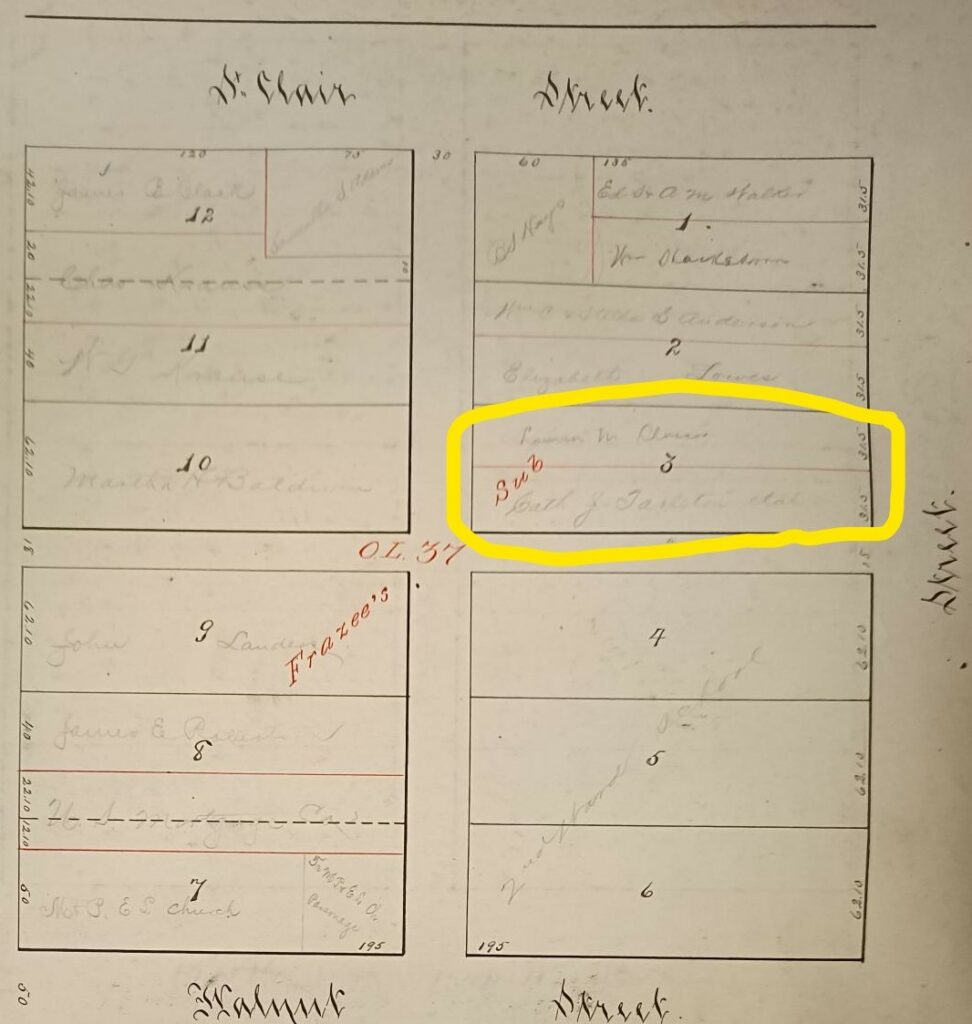

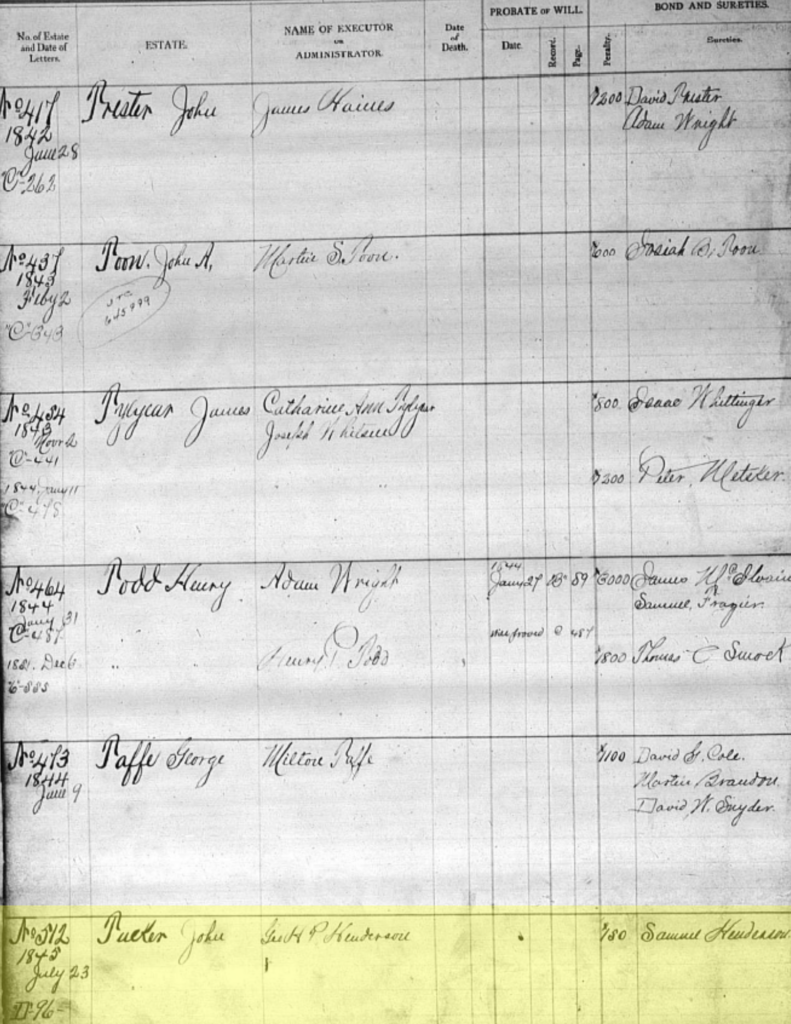

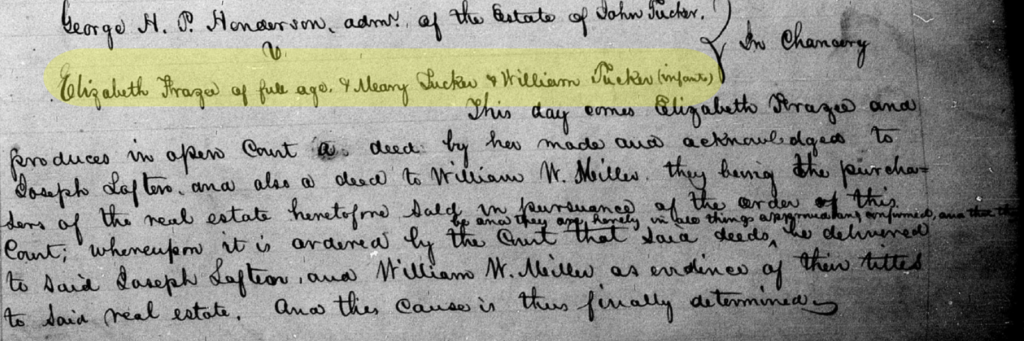

Many court records related to the case simply referred to “the Negro,” but John Tucker was a human being, whose death left his children without a father and fighting for a home. It is unclear what became of Tucker’s wife, but his 13-year-old daughter, Mary (also written as Meary), and his 10-year-old son, William, were left to grieve.[22] Because their father was only about 45 years old at the time of his murder, he was still working to pay off his property. Thus, his death pushed his family into insolvency and legal proceedings that would conclude only in 1851. Court records show that the children, appointed a guardian ad litem, were required to appear in court multiple times regarding the property at Out Lot 37, Lot 3. Ultimately, the court ruled that it be sold at a public auction held at the court house, likely leaving Mary and William penniless.

Lynchings in Indiana from the mid-1800s to 1930 intentionally terrorized Black communities and enforced white supremacy. The State Sentinel reported on August 28, 1845 “that many of the colored residents are in the habit, since the 4th of July, of carrying big clubs, &c.”[23] The article’s author admonished:

We assure them that this is wrong. It tends rather to provoke than allay ill feeling. They are as safe from harm, and as much under the protection of the laws as any member of community; and they should be extremely cautious of doing any thing having a tendency to arouse latent prejudice and hatred in the breasts of those who entertain them. Take our advice. Be quiet. Feel safe. Mind your proper business. Behave yourselves like men.

Clearly, this piece of “advice” rang hollow, as Tucker had minded his “proper business” and did nothing to provoke “ill feeling.” Indianapolis’s Black population, which had grown from 122 residents in 1840 to 405 by 1850, remained vigilant.[24] In 1851, the state furthered discrimination against the minority group when a new constitution was drafted, which prohibited migration of Black Americans into Indiana. Preeminent Indiana historian James Madison summarized the many barriers to equality for Black Hoosiers, noting that “Indiana has never been color-blind. For a long time, the state’s constitution, laws, courts, and majority white voice placed black Hoosiers in a separate and unequal place. . . . separation and discrimination, whether legal or extra-legal, were the patterns of public life for African Americans.”[25] As we continue to reckon with discrimination and racial violence, let us remember John Tucker—father, farmer, husband, and Hoosier.

Notes:

[1] H.W. Beecher, “Rev. H. W. Beecher—the Indianapolis Murder,” Indiana State Sentinel, July 30, 1845, 2, accessed Newspapers.com.

[2] “Affray and Murder,” Indiana State Sentinel, July 10, 1845, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; Gayle Thornbrough and Dorothy L. Riker, eds., The Diary of Calvin Fletcher, vol. III, 1844-1847 (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society, 1974), 164.

[3] “Marion County,” Early Black Settlements by County, Indiana Historical Society, accessed indianahistory.org; James H. Madison, Hoosiers: A New History of Indiana (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2014), 81, 94.

[4] Nicole Poletika, “James Overall: Indiana Free Person of Color and the ‘Natural Rights of Man,'” Untold Indiana, July 15, 2016, accessed https://blog.history.in.gov/james-overall-indiana-free-person-of-color-and-the-natural-rights-of-man/.

[5] Ignatius Brown, Logan’s History of Indianapolis from 1818 (Indianapolis: Logan & Co., 1868), 35.

[6] Poletika, “James Overall: Indiana Free Person of Color.”

[7] State vs. Nicholas Wood, William Ballinger + Edward Davis, Box 045, Folder 081, Location 53-S-6, Accession 2007236, AAIS 116220, Reference COURT0012595, Indiana State Archives, courtesy of historian Leon Bates.

[8] “Marion Circuit Court: Criminal Cases,” Indiana State Sentinel, August 13, 1845, 2, accessed Newspapers.com; State vs. Nicholas Wood, Box 045, Folder 081, Location 53-S-6, Accession 2007236, AAIS 116220, Reference COURT0012595, Indiana State Archives, courtesy of historian Leon Bates.

[9] “Rev. H. W. Beecher,” Indiana State Sentinel; “Marion Circuit Court: Criminal Cases,” Indiana State Sentinel.

[10] “Rev. H. W. Beecher,” Indiana State Sentinel.

[11] W.R. Holloway, Indianapolis: A Historical and Statistical Sketch of the Railroad City, a Chronicle of Its Social, Municipal, Commercial and Manufacturing Progress, with Full Statistical Tables (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Journal Print., 1870), 80-81, accessed Archive.org.

[12] “Affray and Murder,” Indiana State Sentinel, July 10, 1845, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; Testimony of Enoch Pyle, State vs. Nicholas Wood, William Ballinger + Edward Davis, Box 045, Folder 081, Location 53-S-6, Accession 2007236, AAIS 116220, Reference COURT0012595, Indiana State Archives, courtesy of historian Leon Bates.

[13] “Rev. H. W. Beecher,” Indiana State Sentinel; “Marion Circuit Court,” Indiana State Sentinel, August 13, 1845, 2, accessed Newspapers.com.

[14] “Rev. H. W. Beecher,” Indiana State Sentinel.

[15] “Affray and Murder,” Indiana State Sentinel, July 10, 1845, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[16] The Diary of Calvin Fletcher, 165.

[17] “Marion Circuit Court,” Indiana State Sentinel, August 9, 1845, 2, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[18] “Marion Circuit Court: Criminal Cases,” Indiana State Sentinel, August 13, 1845, 2, accessed Newspapers.com.

[19] The Locomotive, August 16, 1845, 2, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[20] “Marion Circuit Court,” Indiana State Sentinel, August 20, 1845, 2, accessed Newspapers.com.

[21] “Murder Cases at Indianapolis,” Evansville Weekly Journal, August 28, 1845, 2, accessed Newspapers.com; Indiana State Prison South, Pardon Book B, page 20, microfilm roll 1, 401-F-2, DOC000690, ICPR Digital Archives, courtesy of historian Leon Bates.

[22] “Affray and Murder,” Indiana State Sentinel, July 10, 1845, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles, 5; “John Tucker,” General Index of Estates, No. 512, July 23, 1845, II-96, emailed to IHB by Indiana Archives and Records Administration Reference Archivist, Keenan Salla; Petition to Sell Paid Real Estate as Insolvent, John Tuckers Estate, George H.P. Henderson, Adm of the Estate of John Tucker, Deceased v.s. Mary Tucker & William Tucker, Infants, Thursday October 16th 1845, and 4th Day of Term, emailed to IHB by Indiana Archives and Records Administration Reference Archivist, Keenan Salla; George H. P. Henderson, Adm. of the Estate of John Tucker v. Elizabeth Frazee, of Full Age, & Meary Tucker and William Tucker (infants), Saturday, August 23rd, A.D., 1851 & 12th Day of the Term, emailed to IHB by Indiana Archives and Records Administration Reference Archivist, Keenan Salla.

[23] “Wrong,” Indiana State Sentinel, August 28, 1845, 2, accessed Newspapers.com.

[24] “Marion County,” Early Black Settlements by County, Indiana Historical Society.

[25] James H. Madison, “Race, Law, and the Burdens of Indiana History,” in The History of Indiana Law, edited by David J. Bodenhamer and Hon. Randall T. Shepard (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2006), 37-59.