“Nestled in the wooded hills of southern Indiana, lies a land of fantasy. . . where it’s Christmas every day.”

Indiana has its fair share of uniquely named towns – Gnaw Bone, Popcorn, Pinhook, Needmore, and Pumpkin Center to name a few. But perhaps the most well-known idiosyncratic place name is Santa Claus in Spencer County, Indiana.

So, how did we get this intriguing sobriquet? Before we get there, we should cover some of the history of the area. The Shawnee, Miami, and Delaware tribes first stewarded the land that later became Spencer County. At the turn of the 19th century, many of these tribes joined Tecumseh’s confederation to oppose white encroachment. However, both U.S. policy and the Treaty of Fort Wayne in 1803 and the Treaty of Vincennes in 1804 opened the land to white settlement. Crossing over from Kentucky, white settlers established permanent homes by 1810 in the Indiana territory near Rockport on the Ohio River, 17 miles southwest of modern-day Santa Claus. But by the mid-nineteenth century when settlers decided to incorporate their new town, they did not originally pay such homage to the Christmas holiday.

As with many place names, the origin of the name Santa Claus is mostly the stuff of legend. The Indiana State University Folklore Archive has preserved three versions of the story behind the name Santa Claus. Below is one example:

Several families settled in the area and decided that they should have a name for their community. They decided on Santa Fe. They applied for a post office to make it official. On Christmas of 1855, everyone was greatly excited at the thought of going to their own brand new post office for their Christmas cards and gifts instead of having to ride to Dale. Unfortunately, a large white envelope with important seals arrived the day before Christmas to reveal that a town in Indiana already was named Santa Fe. Determined to get their post office just as quickly as possible, the citizens of Santa Fe decided to discuss the matter that very night, Christmas Eve. While they were signing, the whole world outdoors became filled with an intense, blinding light, and a little boy came rushing in. ‘The Star, the Christmas star is falling! Everyone rushed out just in time to see a flaming mass shooting down from the heavens and crash into a low distant hill. They considered it an omen of good fortune. Returning to the meeting, it seemed to most natural thing for all the folk to agree that the name Santa Fe should be changed to Santa Claus.

This account is certainly embellished to some extent, seeing as the “Christmas Star” (which appears in the sky every twenty years when Jupiter and Saturn align in the winter sky) made its last appearance in 2020 and did not, in fact, fall from the sky in 1855. However, it gives us an idea of why Santa Claus citizens themselves believe to be their origin story.

However it happened, the townsfolk eventually decided on Santa Claus as a replacement name, and the Santa Claus post office was officially established on May 21, 1856.

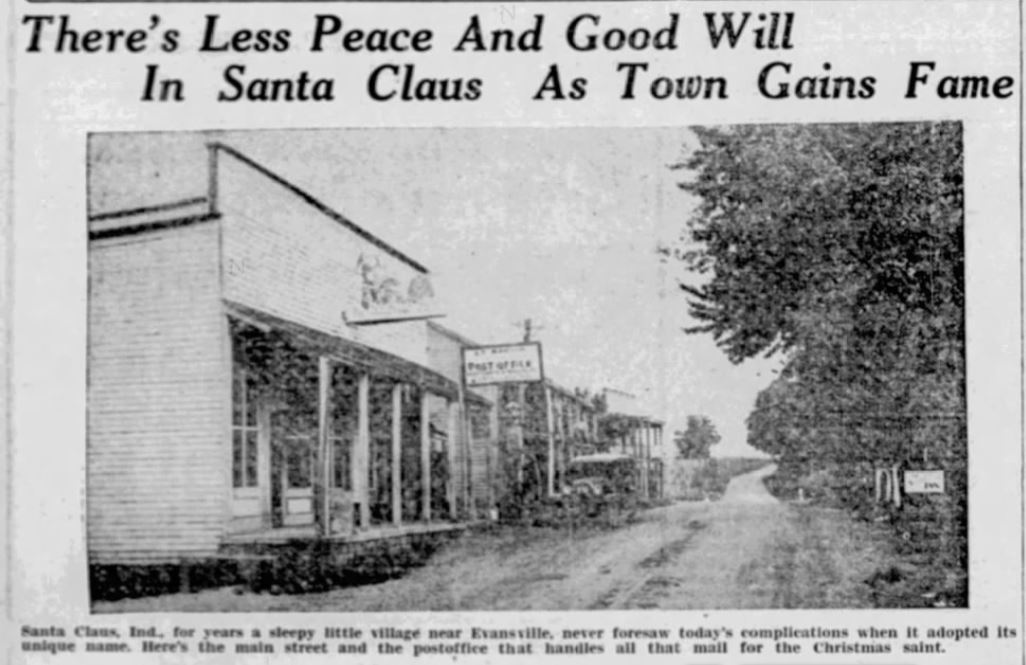

For years, however, the strangely named town was just that – a town with a strange name. It wasn’t until Santa Claus Postmaster James Martin began answering letters written to Saint Nick in the early 20th century that the town began truly embracing its merry moniker. It’s unclear when or why letters to the man at the North Pole began arriving at the Santa Claus, Indiana post office, but in 1914 Martin began writing back, and the tradition only grew from there.

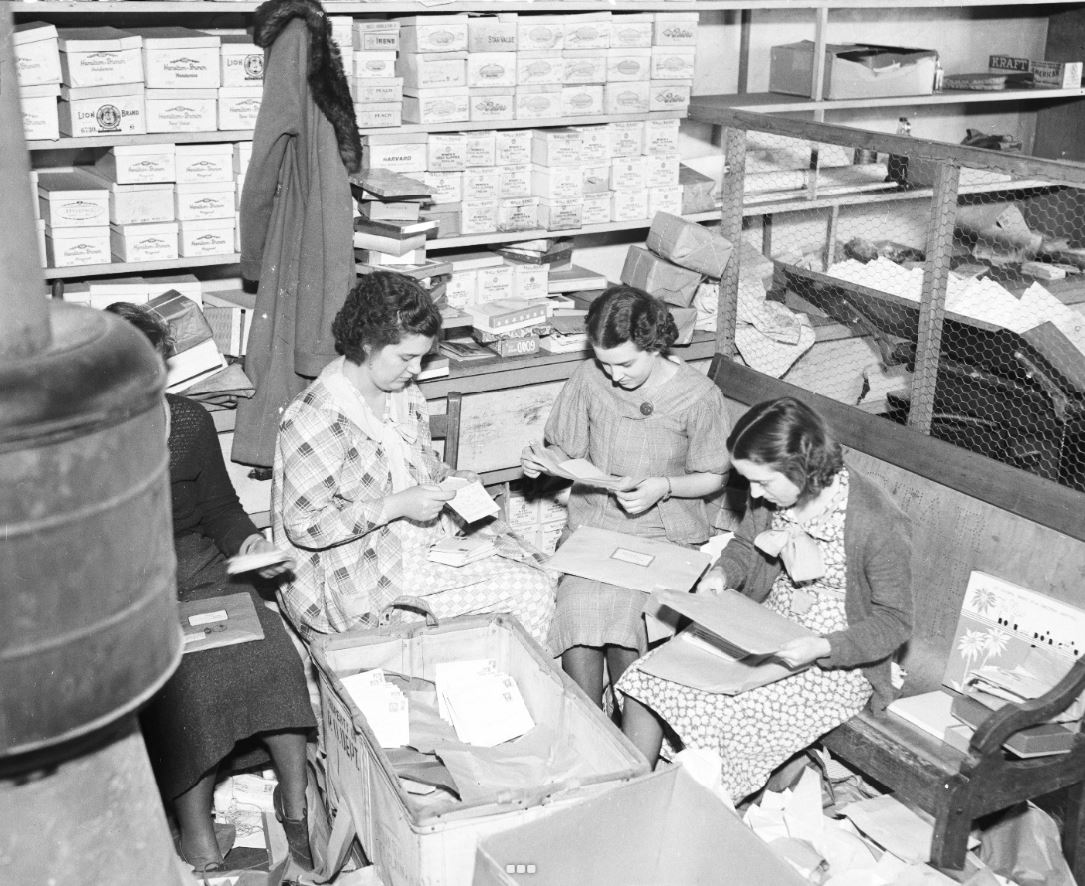

Mail clerks around the country began rerouting letters simply addressed “Santa Claus” to the Indiana town for Martin to handle. Parents began writing notes with enclosed letters or packages to be stamped with the Santa Claus postmark and sent back, making the letters and gifts under the tree on Christmas morning that much more authentic.

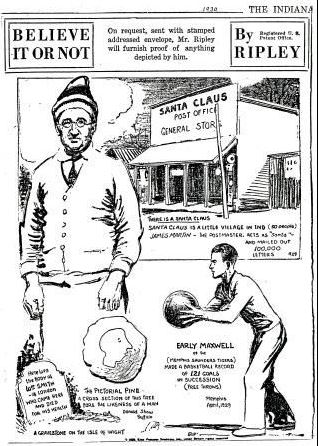

By 1928, Martin and his clerks were, not unlike Santa and his elves, handling thousands of letters every holiday season and were garnering enough attention to catch the eye of Robert Ripley of Ripley’s Believe It or Not. Before Ripley’s was an after school tv show and before it was a coffee table book you bought at your school’s annual Scholastic Book Fair, it was a syndicated newspaper panel that shared interesting tidbits and oddities from around the world. And on January 7, 1930, the oddity in question was none other than Santa Claus, Indiana.

It was a brief mention, but it was enough. The next Christmas, Martin reported that the number of parcels and letters coming through his post office had grown exponentially, adding:

I guess my name ought to be Santa Claus, because I have to pay out of my own pocket for handling all this mail. I’ve hired six clerks to help out and I recon it’s going to cost $200. But it advertises the town and besides lots of folks from all around come out to the store to see us sending out the mail.

With great fame comes great scrutiny, or at least it did in this case. By 1931, the Associated Press reported that officials in Washington were considering changing the name of the town as the stress put on the postal system during the holiday season was becoming too much to handle. Christmas lovers across the country bemoaned the potential loss, but none so loudly as the citizens of Santa Claus, who contacted their U.S. Senator James Watson and U.S. Representative John Boehne, of Indiana.

Watson and Boehne got to work for their constituents. Representative Boehne notified the USPS that the entire Indiana delegation would oppose the name change if it were to go forward. Senator Watson took a more direct route and went straight to Postmaster General Walter Brown to assure him that, “The people won’t want it changed. “ “The name must not be changed nor the office abolished.”

In the end, of course, the citizens were able to preserve their beloved town’s name, and the tradition continued to grow.

Entrepreneurs, hoping to cash in on the Christmas spirit, began to take notice of the small town. In 1935, Vincennes speculator Milt Harris founded the business called Santa Claus of Santa Claus, Incorporated. Harris erected Santa’s Candy Castle, the first tourist attraction in town. Built to look like a fairy castle and filled with candy from project sponsor Curtiss Candy Company, the Candy Castle was the centerpiece of what Harris dubbed Santa Claus Town, a little holiday village of sorts made up of his business ventures. The castle would eventually be joined by Santa’s Workshop and a toy village.

Across town, a different, similarly named business, Santa Claus, Incorporated, brainchild of Chicago businessman Carl Barrett, built another Yuletide monument, a 22-foot tall statue of Santa Claus purportedly made of solid granite. This colossal Kris Kringle was the start of a second Christmas themed landmark, this one called Santa Claus Park. All of this in a town of fewer than 100 people.

Both attractions were dedicated during the Christmas season of 1935, but all the holiday spirit in the world wasn’t enough to keep the peace between Harris and Barrett.

By 1935, the town of Santa Claus, Indiana was home to two organizations – Santa Claus, Incorporated, owned by Carl Barrett, and Santa Claus of Santa Claus, Incorporated, owned by Milt Harris. Barrett and Santa Claus, Incorporated were developing Santa Claus Park, which featured the 22-foot Santa Claus statue. Harris and his company were developing Santa Claus Town, featuring Santa’s Candy Castle. Barrett filed suit against Harris, alleging that the latter had no right to use a name so similar to its own. Meanwhile, Harris filed suit against Barrett because Barrett had bought and was building Santa Claus Park on land that had been leased to Harris by the previous owner.

By 1935, the town of Santa Claus, Indiana was home to two organizations – Santa Claus, Incorporated, owned by Carl Barrett, and Santa Claus of Santa Claus, Incorporated, owned by Milt Harris. Barrett and Santa Claus, Incorporated were developing Santa Claus Park, which featured the 22-foot Santa Claus statue. Harris and his company were developing Santa Claus Town, featuring Santa’s Candy Castle. Barrett filed suit against Harris, alleging that the latter had no right to use a name so similar to its own. Meanwhile, Harris filed suit against Barrett because Barrett had bought and was building Santa Claus Park on land that had been leased to Harris by the previous owner.

A judge put an injunction on Santa Claus Park, meaning Barrett could not move forward with development. Eventually, this tongue twister of a case went all the way to the Indiana Supreme Court, which ruled in 1940 that both companies could keep using their names and overturned the injunction, meaning that the plans for Santa Claus Park could move forward, regardless of Harris’s lease.

However, the protracted legal battle, combined with wartime rationing, which impacted tourism due to gasoline and tire shortages, took a toll on both attractions. By 1943, cracks ran through the base of the giant Santa Statue and the Candy Castle had closed its doors.

With the end of the war came new opportunities. In 1946, retired Evansville industrialist and father of nine, Louis Koch, opened Santa Claus Land after being disappointed that the town had little to offer visiting children hoping to catch a glimpse of the jolly man in the red suit. This theme park, reportedly the first amusement park in the world with a specific theme, included a toy shop, toy displays, a restaurant, themed rides and, of course, Saint Nicholas.

This was no run of the mill Santa Claus, though. Jim Yellig would become, according to the International Santa Claus Hall of Fame, “one of the most beloved and legendary Santas of all time.” Yellig had donned the red and white suit at the Candy Castle and volunteered to answer letters to Santa for years before becoming the resident Santa at the new park, a position which he held for 38 years. During his tenure as Saint Nick, Yellig heard the Christmas wishes of over one million children.

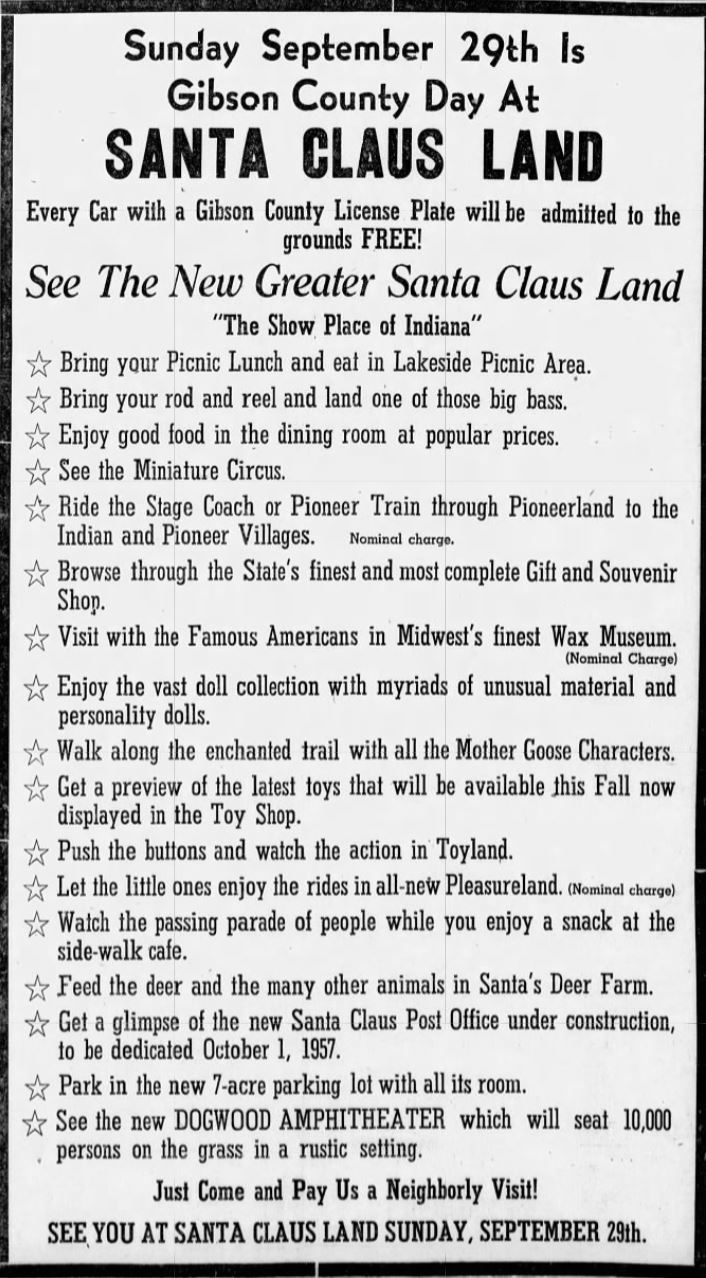

Throughout “Santa Jim’s” tenure, Santa Claus Land continued to grow, thanks in large part to Louis Koch’s son, Bill Koch, who took over operation of the park soon after its founding. By 1957, the park offered a “miniature circus,” a wax museum, Santa’s Deer Farm, and an outdoor amphitheater. Live entertainment shows, such as a water ski show, started and in the early 1970s rides such as Dasher’s Seahorses, Comet’s Rockets, Blitzen’s Airplanes, and Prancer’s Merry-Go-Round were added. And in 1984, the Koch family expanded from a strictly Christmas-themed park to include Halloween and Fourth of July sections and changed its name to Holiday World. Still in operation today as Holiday World & Splashin’ Safari, the theme park, which features what are considered some of the best wooden roller coasters in the world, welcomes over 1 million people per year.

Today, the town of Santa Claus is more “Christmas-y” than ever. Many of its 2,400 residents live in Christmas Lake Village or Holiday Village on streets with names like Poinsettia Drive, Candy Cane Lane, or Evergreen Plaza. The Candy Castle was renovated and reopened in 2006 and is known for its wide selection of cocoas and its Frozen Hot Chocolate. Carl Barrett’s 22-foot Santa Statue was restored by Holiday World in 2011 and now welcomes tourists from all over the world. Visitors to Holiday World can stay at Lake Rudolph Campground and RV Park or Santa’s Lodge. Every Christmas season, the small town comes alive with festivals, parades, and even Christmas fireworks. And, of course, dedicated volunteers still answer children’s letters to Santa, even if they sound a little different than they used to.