We’ve compiled our top 10 most read Blogging Hoosier History posts. We are searching for guest bloggers to kick off 2017, so check out the Guest Blogger Guidelines if you think you could be a good fit. Thank you for your readership!

- World War II Comes to Indiana: The Indiana Ammunition Plant, Part 1 & Part 2

During WWII at the Charlestown smokeless powder ordnance facility, women and African American employees, groups that often faced exclusion or discrimination in the workplace, contributed to the plant’s nationally-recognized production accomplishments.

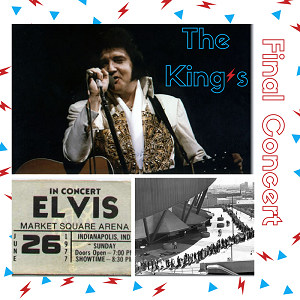

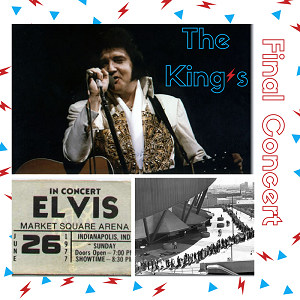

2. The King’s Final Bow: Elvis’s Last Concert in Indianapolis

Elvis Presley, known around the world as the King of Rock ‘n’ Roll, thrilled audiences for decades with his legendary swagger, good looks, and unique vocal stylings. Among his many concerts over the years, the one that garners much historical attention is his final performance, which occurred at Indianapolis’s Market Square Arena on June 26, 1977. His concert, to a crowd of nearly 18,000 people, inspired copious press attention.

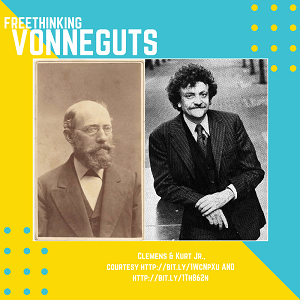

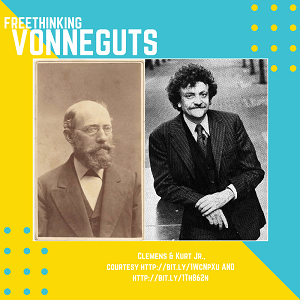

3. The Shared Humanism of Clemens and Kurt Vonnegut

The German-American community in Indianapolis, largely a product of mid-nineteenth century immigration, had a strong heritage of freethought (open evaluation of religion based on the use of reason). In particular, Clemens Vonnegut, the patriarch of the Vonnegut family and lifelong freethinker, openly displayed his religious dissent through writings and community activism. This, in turn, influenced his family and the literary style of his great-grandson, novelist Kurt Vonnegut, especially the younger man’s ideas concerning God, religion, science, and ethics.

4. Lincoln’s Forgotten Visit to Indianapolis

Aside from two visits in 1844 and 1861, most Lincoln fans would be hard-pressed to identify the other time that Lincoln visited Indiana for political purposes. It happened on September 19, 1859 in Indianapolis, where he delivered a speech so obscure that it was largely forgotten until 1928 when a researcher rediscovered it in an issue of a short-lived Indianapolis newspaper, the Daily Evening Atlas.

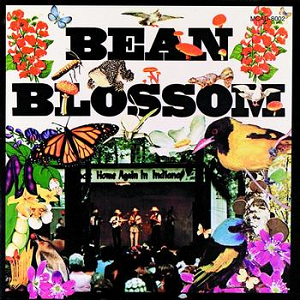

5. Bill Monroe in Indiana: From Lake to Brown County, Oil to Bluegrass

William “Bill” Monroe’s Hoosier roots run deep. While Bill was born and raised in Kentucky, he moved to northwest Indiana in 1929 when was he was just eighteen years old. His brother Charlie started a job at the Sinclair Oil refinery in Whiting, Indiana, and sent for Bill and their other brother, Birch. It was the start of the Great Depression, and the crowds outside the refinery of eager job seekers grew large enough that the police moved them so the street cars could get through.

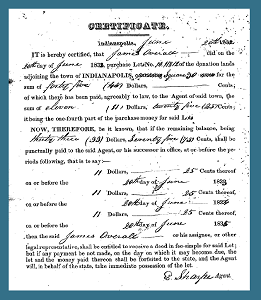

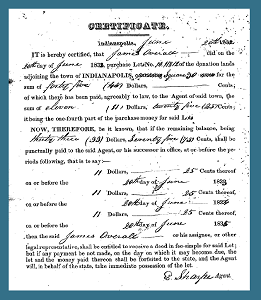

6. James Overall: Indiana Free Person of Color and the “Natural Rights of Man”

As population increased, so did discrimination against African Americans in Indiana, prompting the Indiana General Assembly to pass prohibitive laws. Land ownership offered African Americans the opportunity to circumvent this oppression. James Overall, a free black man, purchased land in Corydon, Indiana as early as 1817 before moving and acquiring land in Indianapolis in 1830. The ownership of land afforded him prominence in his community, as did his work as a trustee for the African Methodist Episcopal church.

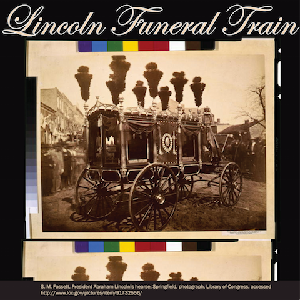

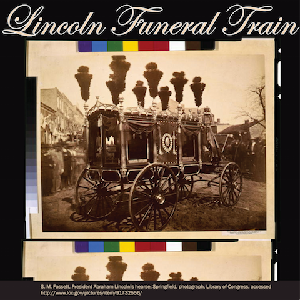

7. The Lincoln Funeral Train

On April 30, the Lincoln funeral train passed into Indiana where Lincoln spent much of his youth (1816-1830). The War Department directed: “The route from Columbus to Indianapolis is via the Columbus and Indianapolis Railroad, and from Indianapolis to Chicago via Lafayette and Michigan Railroad. In order to guard against accidents, trains will not run faster than twenty miles per hour.” The train stopped in Richmond first, at 3 a.m., to the sound of tolling bells and a crowd of somewhere between 12,000 and 15,000 people. Here, Governor Oliver P. Morton and almost 100 elected officials paid their respects. The governor and other several other high-ranking officials boarded the train for the trip to the state capital.

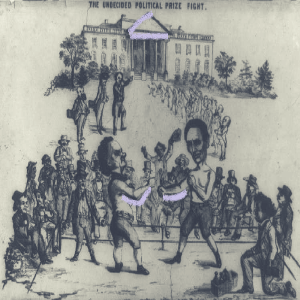

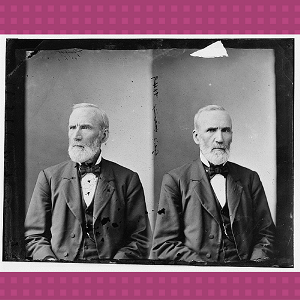

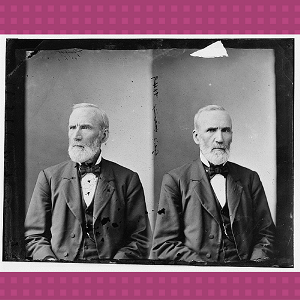

8. George Washington Julian: Radical Representative of Moral Conviction

Long before Indiana Governor ran as vice president, another Hoosier sought the office in 1852. Centerville’s George Washington Julian was a radical political leader defined by his strong moral convictions. During a period marked by slavery, Civil War, monopolies, and discrimination against African Americans, immigrants, and women, Julian tirelessly advocated for abolition, equal rights, and land reform. He served in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1849-1851, served as an attorney in several fugitive slave cases in the 1850s (one which included a daring escape plan), ran for vice president on the Free Soil ticket in 1852, and again served as the U.S. House from 1861-1871.

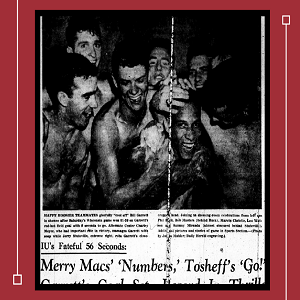

9. Bill Garrett and the Integration of Big Ten Basketball, Part 1

In 1947, Jackie Robinson made history when he broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball. Robinson set the precedent, and in the years following, many African American athletes would follow his lead to join professional league teams. In 1948, just one year after Robinson’s debut with the Dodgers, Indiana witnessed its own trailblazer in sports, as Shelbyville’s Bill Garrett broke the ironically named “gentleman’s agreement” that had barred African Americans from playing Big Ten college basketball.

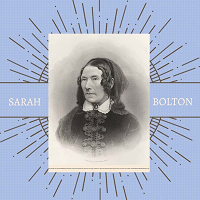

10. Sarah Bolton: “Hoosier Poetess” and Women’s Rights Advocate

10. Sarah Bolton: “Hoosier Poetess” and Women’s Rights Advocate

Women’s rights advocate, poet, and author of “Paddle Your Own Canoe” and “Indiana,” Sarah T. Bolton was born as Sarah Barrett in Newport, Kentucky circa 1814. Her family moved to Indiana when she was a young child, and when much of the state was still unsettled. According to the Life and Poems of Sarah T. Bolton, while growing up on her family’s farm near Vernon, she was exposed to the pioneer experience, living in a log house and clearing the fields.

10.

10.