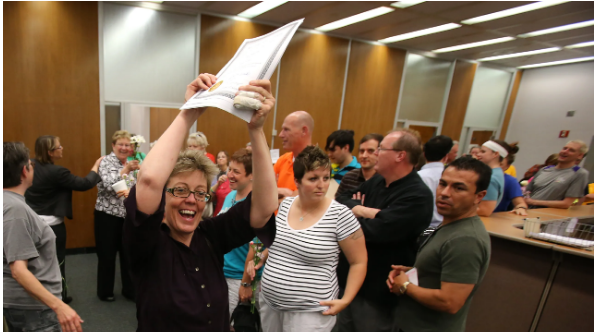

Before same-sex marriage was legally recognized across the United States in 2015, Quaker organizations in Indianapolis had upheld their roles as LGBTQ allies by marrying same-sex couples, like Mary Byrne and Tammara Tracy, in informal religious meetings. From their advocacy of the abolitionist movement to more modern issues of social justice, the Religious Society of Friends—or Quakers—have a unique relationship with marginalized communities. In Indianapolis, this relationship becomes even more intriguing when looking at Quaker connections to the LGBTQ community, specifically the activism of the North Meadow Circle of Friends, located at 1710 North Talbott Street, in the 1980s. Their meeting house served not only as a site for political engagement, but also as a location where same-sex couples could be wed long before same-sex marriage was legalized. The North Meadow Circle of Friends’ devotion to and involvement in issues central to the LGBTQ community provides a contrasting narrative to the prevailing one that all religious groups have historically opposed same-sex marriage.

Quakers believe God resides in every individual, providing them the ability to discern the will of God. They see each human life as possessing an unique worth, and they rely on the human conscience as the foundation of morality.[1] Throughout history, Quakers have sought to improve their own lives by placing an emphasis on education and the improvement of the lives of others. Friends have co-existed with Native Americans and supported the abolition of slavery. Activism involving abolitionism began with the adoption of strict policies regarding slavery, and by 1780, all Quakers in good standing had freed their slaves.[2] In addition, many Quakers’ homes, including that of Indiana residents Levi and Catharine Coffin, served as “stations” on the Underground Railroad.[3]

This legacy of embracing underrepresented communities is one reason many LGBTQ individuals in the 20th and 21st centuries have found acceptance in the Religious Society of Friends, including the North Meadow Circle of Friends. While generally the Quaker faith has a long history of inclusion, the religion itself has split over LGBTQ inclusion and issues. Some Quaker churches continue to view “the grouping of homosexuality and transsexuality with sexual violence and bestiality” and will only acknowledge a marriage between a man and a woman.[4] This has caused a divide in the Quaker community, as other Quaker churches view being an LGBTQ ally as a foundation of their faith. The North Meadow Circle of Friends has chosen to position itself as one of those allies through association with national queer-friendly organizations and conferences.

One such organization is the Friends for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Concerns (FLGBTQC), a North American Quaker faith community that gathers twice yearly and is a proponent of Quaker support for the LGBTQ community. The FLGBTQC has collected minutes of same-sex marriages and other commitment ceremonies from across the nation, one of which happens to be of the North Meadow Circle of Friends. On April 12, 1987, the North Meadow Circle of Friends wrote to the FLGBTQC that they “affirm the equal opportunity of marriage for all individuals, including members of the same sex.”[5]

In addition to the official beliefs expressed by the North Meadow Circle of Friends in Quaker conferences, their community involvement during the 1980s and beyond demonstrates their commitment to marginalized communities. The Friends engaged in political activism by offering their meeting house as a place in which to mobilize and plan protests. The location on North Talbott Street is mentioned several times in articles in The New Works News, a gay Indianapolis periodical, as a location for meetings in preparation for a “March on Washington” to protest violence against the LGBTQ community.[6] The planning committee held at least two meetings there in the course of organizing the march, which was broadly intended to “show that ‘we are out of the closet and we are not going back.’”[7] In addition to using the meeting house for activism, Indianapolis Friends published the phone numbers of Quaker organizations, like the Friends for Lesbian & Gay Concerns, in gay business and service directories.[8] This Quaker support network appeared numerous times in LGBTQ directories around the early 1990s, indicating the connections between the Friends and the larger LGBTQ community in the city.

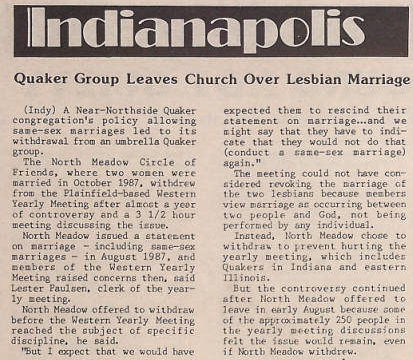

At times, the North Meadow Circle of Friends’ devotion to the LGBTQ community superseded even their own relationships with Quaker organizations. The Friends at Talbott Street chose to withdraw from the Western Yearly Meeting after controversy followed the 1987 wedding for two women at the Indianapolis meeting house. Since North Meadow refused to rescind their statement on same-sex marriage or promise not to hold future same-sex weddings, they chose to withdraw from the meeting to prevent further fractures among the Friends.[9] The 2004 wedding of Mary Byrne and Tammara Tracy, a same-sex couple married at an Indianapolis Quaker meeting, would reaffirm support for the LGBTQ community and the recognition of same-sex relationships.

An interview conducted by the Indiana Historical Society illuminates Mary Byrne’s and Tammara Tracy’s connection to the Quaker church. Tracy recalled learning that Byrne was a Quaker early on in the relationship, explaining “I kept asking her to take me to a Quaker meeting because they are a little different than just going to a church service where you can walk in the door and be anonymous and sit in the back pew and do that kind of thing.”[10] Tracy described her first meeting as “a really big click,” and recalled that it was a “wonderful experience because it truly is the first religious experience in which every single part of myself felt welcomed. Not tolerated, not passed over, but actually, genuinely welcomed.”[11] Through the Quaker meetings, Tracy and Byrne were able to get to know each other better and, according to their recollections, they even attended a Quaker lesbian conference.

After being together for almost four years, in 2004 they asked to be married at their Quaker meeting. Byrne explained that a “Quaker meeting is un-programmed . . . whoever wanted to speak during it could speak and then at some point we got up and spoke our vows to each other and then we had a party.”[12] As the wedding was not legally recognized, all 135 attendees signed a certificate saying that the marriage occurred. After a federal judge ruled that Indiana’s ban on gay marriage was unconstitutional in 2014, the couple legalized their marriage.

While many churches still grapple with whether to accept or wed LGBTQ individuals, decades ago the North Meadow Circle of Friends was unwavering in its support of both. In fact, North Meadow demonstrated how a church could actually enrich same-sex relationships. For the queer community, Indianapolis’s Circle of Friends provided another safe or third space environment, in addition to bars and public parks, in which they could find acceptance and gain equal recognition of their rights and relationships.

Sources:

[1] “What Is Quakerism?,” accessed Berkeley Friends Meeting.

[2] Rae Tyson. “Our First Friends, The Early Quaker,” Pennsylvania Heritage, 2011.

[3] “About Levi Coffin,” accessed Levi and Catharine Coffin State Historic Site.

[4] Megan Creighton, “Quaker Church Splits Over Disputes on LGBT Issues,” The Crescent, November 10, 2017, accessed George Fox University.

[5] Marriage Minutes, “North Meadows Circle of Friends,” April 12, 1987, accessed Friends for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Concerns.

[6] “’March on Washington’ April Meeting Report,” The New Works News 6, no. 8 (May 1987): 6, accessed Chris Gonzalez GLBT Archives.

[7] “The ‘March’ Is Thus Far A ‘Stroll:’ ‘A Report on the March on Washington Committee,’” The New Works News 6, no. 5 (February 1987): 12, accessed Chris Gonzalez GLBT Archives.

“The ‘March on Washington’ Gains Momentum,” The New Works News 6, no. 6 (March 1987): 5, accessed Chris Gonzalez GLBT Archives.

“’March On Washington’ April Meeting Report,” The New Works News 6, no. 8 (May 1987): 6, accessed Chris Gonzalez GLBT Archives.

[8] “NWN’s Gay Business & Service Directory,” The New Works News 10, no. 2 (November 1990): 21, accessed Chris Gonzalez GLBT Archives.

“NWN’s Gay Business & Service Directory,” The New Works News 10, no. 4 (January 1991): 16, accessed Chris Gonzalez GLBT Archives.

[9] “Quaker Group Leaves Church Over Lesbian Marriage,” The New Works News 8, no. 1 (October 1988): 6, accessed Chris Gonzalez GLBT Archives.

[10] Mary Byrne and Tammara Tracy, interview by Mark Lee, January 17, 2015, 57, Indianapolis/Central Indiana LGBT Oral History Project, Indiana Historical Society.

[11] Ibid., 57-58.

[12] Ibid., 60.