Embroidered with resorts and mineral springs, French Lick Valley served as a veritable playground for Americans at the turn of the 20th century. Hotels in West Baden and French Lick offered all the creature comforts money could buy. One could luxuriate in mud baths, bird watch from marbled verandas, and be moved to tears at an opera house. When nestled in the hills of southwestern Indiana, daily responsibilities were but a glint in the rearview mirror. But for some, the Valley was a hotbed of violence and intimidation. In early June 1902, “Friends” penned a letter informing Black waiters, “There is 35 sticks of 45 per cent dynamite in hiding now to blow you up and there is also ammunition at the same place. Every house in West Baden, French Lick, Hillham and in the valley that has colored people in them will be blown up.”[1]

The letter reported that fifty-six locals had gathered in the countryside, plotting to drive out the region’s Black population. The conspirators were likely the same individuals who had recently installed a sign in West Baden bearing “the proverbial skull and cross bones” associated with sundown towns.[2] According to Lin Wagner, director emeritus of the French Lick West Baden Museum, “’The hotels were building and booming in the late 1800s, the south was undergoing reconstruction and a lot of blacks were moving north. West Baden Springs Hotel owner Lee W. Sinclair brought workers up from the south to work as nannies, bellmen, maids, porters and waiters; vital to the day to day operations and success of his West Baden resort.'”[3] As the Black community grew, the “laboring classes among the white people” conspired to dispel its workforce.

Between 1902 and 1908, newspapers reported on an emergent “race war” in the French Lick Valley. Just days after the letter was dispatched to Black waiters, as well as the property owners who rented to them, Secret Service officials descended on the area.[4] They warned the conspirators, who had appointed themselves the “Committee of Regulators,” that if they were caught with firearms they would be jailed for “inciting a riot.” And while “Uncle Sam” had taken “a Hand,” as the Huntington Weekly Herald phrased it, it is unclear if any of the “ringleaders” actually faced arrest or imprisonment.[5]

Punitive lip service was more likely, as Deputy U.S. Marshall John Ballard reportedly feared arrests would make the situation more volatile. In analyzing the “race war,” historian Emma Lou Thornbrough noted that “although there were no statutory laws forbidding black settlement,” it was “enforced not only by public opinion but also by sheriffs and other local officers, that decreed blacks could not settle in the town or stay overnight.” This aligns with the Bedford Weekly Mail‘s report that “several of the most objectionable” Black residents complied with a “quiet” order to leave the area during the conflict.[6]

Referencing the events in West Baden and similar occurrences in “several towns along the line of the Monon railroad,” Rev. Edward Gilliam wrote to the editor of the Indianapolis News, asking “Where are my people to go? What are we to do?”[7] He argued that these conflicts represented the larger struggle for Black people to support themselves in post-Reconstruction America. Rev. Gilliam wrote, “With factory doors, mercantile opportunities and other avenues of earning a livelihood closed against us,” it was particularly shameful to “be notified that we shall be permitted to choose our fields of labor only upon the approval and consent of a lot of men who defy the laws of the country.” He begged the question “is it not time for those who favor fair play to all men to speak out and emphatically say that Indiana shall not be disgraced by such unlawful proceedings?” Black Americans were barred from employment and subsequently condemned for their destitution.

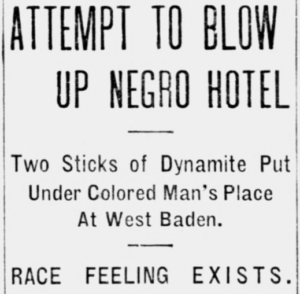

Just after midnight on June 5, 1908, sections of the Valley illuminated with gunfire. A few hours later, the sound of explosions plucked dozens of waiters from slumber at the Jersey European Hotel. “Frightened so badly that they could scarcely speak,” they rushed into the street as sticks of dynamite hammered the west side of the building.[8] Many boarders at the Jersey European—operated by Black proprietor Charles “Champ” Rice—were Black employees of the West Baden Springs Hotel.[9] While no one was physically harmed, the blast damaged the structure and succeeded in driving many residents from the area.

Journalists speculated about the perpetrators’ motive, but generally concurred that the violence was intended as retribution for the dismissal of white waitresses for the West Baden Springs Hotel, known as the “Eighth Wonder of the World.”[10] Reportedly, hotel manager Lee Sinclair had recently fired about forty waitresses and replaced them with Black men from Louisville.[11] According to Thornbrough, “Just as custom and prejudice, rather than law, assigned blacks to certain residential areas, so custom and prejudice decreed that only certain kinds of employment were open to ‘colored persons’—usually seasonal jobs that whites disdained.” U.S. Census reports at the time noted the majority of Black men worked as servants and porters.

Sinclair justified his decision to replace the waitstaff as “trying to better moral conditions.” However, an anonymous writer informed the Indianapolis News that Sinclair was induced by the “jealousy of a woman for the waitresses. She has been trying to make this change for the last year.”[12] It is unclear if the woman was part of hotel staff or had a personal relationship with Sinclair. Regardless of its impetus, the resultant hostility caused many of the waiters and residents to flee the area.[13] On the precipice of a “race war,” Marshall John Ballard returned to West Baden, seeking to identify those who initiated the attacks. He was generally met with silence, especially from fearful Black residents who had chosen to remain in the Valley. A night watchman also had little to offer, as he reportedly fled in search of law enforcement when the shots began ringing.

Tensions were so heightened that the Brazil Daily Times predicted the state militia would be dispatched.[14] The Muncie Evening Press echoed, “Other attacks upon the place are feared unless police protection is furnished in this place. The community has always been opposed to negroes.”[15] Nevertheless, John Felker, owner of a building that housed the displaced individuals, refused to expel them, “even if the alternative is leveling the building to the ground with dynamite.”[16]

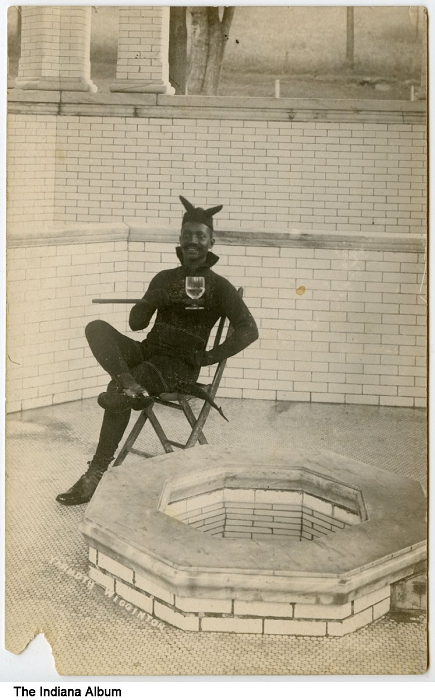

Perhaps the war would not be so easily won. The violence seemed to disperse as quickly as it emerged, or at least reports of it ceased to appear in newspapers. And while many Black residents fled, refugees in their own country, others stayed and nurtured the remaining community. In 1909, Rev. Chas. Hunter wrote to the Indianapolis Recorder about the burgeoning Black-owned businesses in the French Lick Valley.[17] He noted that members of the “superior class,” like hotel porter S.C. Pitman and news dealer H.L. Babbage, lived in “good houses, furnished up-to-date.” W.O. Martin owned a tailoring business and Mrs. W.L. Alexander and Mrs. W. M. Scott did “a fine business” as dress makers. James Gibbs, “well known in Indianapolis,” excelled as head waiter at French Lick Springs Hotel. Rev. Hunter concluded his letter to the editor by quipping “my old friend Wiggington plays the ‘devil’ as usual'” in his role as the French Lick Springs Hotel’s mascot, Pluto Water.

Rev. Hunter’s editorial resonated with a Recorder subscriber, who added in the following issue that George Jones operated a dry cleaning business and tailoring establishment, both of which did “a very heavy summer business.”[18] George’s wife, Myldred, started a music class, hoping to teach “her former pupils and also people musically interested.”

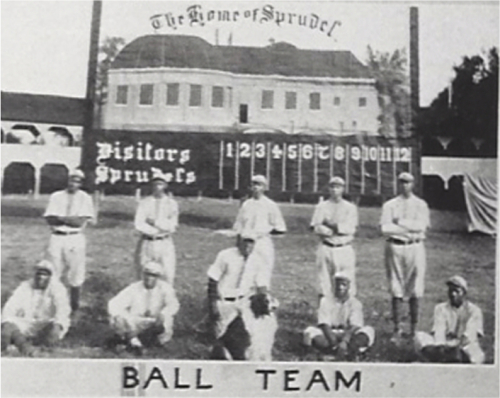

Recreation and the humanities kept pace with business endeavors in the Valley’s Black community. Members of the Ladies Culture Club met that spring to discuss issues of peace. They listened as Mrs. W.O. Martin delivered a talk “On why should we hustle for a living.”[19] Young residents organized a literary society to explore matters of art and culture. In April 1909, the First Baptist Church was dedicated. Hugh Rice and J.P. Cook presented tithes on behalf of their fellow waiters at the West Baden and French Lick hotels.[20] After church, one could watch the West Baden Sprudels (managed by hotel proprietor Champ Rice) play the French Lick Plutos.

Rice’s Jersey European Hotel withstood the Summer of 1908. In ads printed in The New York Age in 1912, he promised those “in bad health” the benefits of the Jersey’s spring waters for just $1.00 per day.[21] Indeed, those who hailed from the Big Apple took him up on the offer, as well as those from cities like Chicago, Pittsburgh, Little Rock, Cleveland, and Chattanooga. Providing the Jersey European with competition, the Waddy Hotel opened in 1913. It served Black patrons like noted Indianapolis journalist Lillian Thomas Fox and, years later, famed boxer Joe Louis.

Black communities and institutions continued to grow in Indiana cities during the Progressive Era. In trying to make a livelihood, Black Americans had to contend with displacement, vandalism, violence, and eventually the organized efforts of the Klan. By 1923, fiery crosses stretched across Southern Indiana’s “little valley,” as 100 members were initiated into the hate group.[22] Despite the shadow cast by Jim Crow discrimination, Black Americans continued to answer the questions “Where are my people to go? What are we to do?” through community-building and fellowship.

Sources:

[1] “Race Troubles Imminent,” The Daily Mail (Bedford, IN), June 17, 1902, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[2] The Huntingburgh Independent (IN), June 21, 1902, 2, accessed Newspapers.com.

[3] Dawn Mitchell, “Revival at the Last African American Church in West Baden,” IndyStar, September 19, 2018, accessed IndyStar.com.

[4] “Government Takes a Hand,” Fort Wayne News, June 24, 1902, 6, accessed Newspapers.com; “Uncle Sam Now Takes a Hand,” Huntington Weekly Herald, June 27, 1902, 6, accessed Newspapers.com; Bedford Weekly Mail, June 27, 1902, 4, accessed Newspapers.com.

[5] “Uncle Sam Now Takes a Hand,” Huntington Weekly Herald, 6.

[6] Bedford Weekly Mail, June 27, 1902, 4; Emma Lou Thornbrough, Indiana Blacks in the Twentieth Century (Bloomington, Indiana University Press: 2000), 3.

[7] “The Negro in Indiana,” Indianapolis News, June 24, 1902, 6, accessed Newspapers.com.

[8] Quote from “Dynamite Used to Threaten Negroes,” Indianapolis News, June 5, 1908, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; “Attempt to Blow up Negro Hotel,” Richmond Palladium, June 5, 1908, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[9] “Use Dynamite on Hotel Owned by Colored Man,” Muncie Evening Press, June 5, 1908, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[10] “Attempt to Blow up Negro Hotel,” Richmond Palladium, 1; “Dynamite Explosion Frightens Negroes,” The Republic (Columbus, IN), June 5, 1908, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; “Dynamite Used to Threaten Negroes,” Indianapolis News, 1; “Race War at West Baden,” Greencastle Herald, June 5, 1908, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[11] Bedford Daily Mail, June 2, 1908, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; “Change to Male Waiters,” Indianapolis News, June 3, 1908, 10, accessed Newspapers.com; Thornbrough, Indiana Blacks in the Twentieth Century, p. 6.

[12] “Dynamite Used to Threaten Negroes,” Indianapolis News, 1; Letter-to-the-Editor, X, “West Baden Waitresses,” Indianapolis News, June 12, 1908, 9, accessed Newspapers.com.

[13] “Use Dynamite on Hotel Owned by Colored Man,” Muncie Evening Press, June 5, 1908, 1; “All Quiet at West Baden,” Indianapolis News, June 6, 1908, 15, accessed Newspapers.com.

[14] “Riot Quiets Down,” Brazil Daily Times, June 6, 1908, 2, accessed Newspapers.com.

[15] “Use Dynamite on Hotel Owned by Colored Man,” Muncie Evening Press, June 5, 1908, 1.

[16] “All Quiet at West Baden,” Indianapolis News, 15.

[17] Letter-to-the-Editor, Rev. Chas. Hunter, “French Lick,” Indianapolis Recorder, January 16, 1909, 2, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[18] A Subscriber, “French Lick,” Indianapolis Recorder, January 23, 1909, 3, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[19] “French Lick,” Indianapolis Recorder, April 10, 1909, 3, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[20] “French Lick,” Indianapolis Recorder, April 24, 1909, 3, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[21] “Jersey European Hotel, West Baden, Ind.,” New York Age, August 8, 1912, 2, accessed Newspapers.com; Ad, “Jersey European Hotel & Baths,” New York Age, October 3, 1912, 3, accessed Newspapers.com.

[22] “French Lick Shows Interest,” Fiery Cross, April 6, 1923, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “French Lick, Ind., Has Klan Ceremony,” Fiery Cross, July 6, 1923, 18, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.