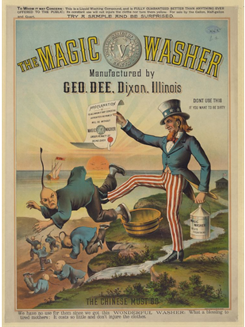

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism reported that anti-Asian hate crimes increased by approximately 339 percent in 2022. Indiana was no exception. In 2023, the Bloomington community was shocked when a white woman named Billie Davis stabbed an IU student, who has chosen to remain anonymous, on a public bus because she “looked” Chinese. Events like this stunned the nation and forced Americans to reconsider their historical treatment of Chinese immigrants and, more importantly, where they fit into American society today.

This renewed “Chinese question” has warranted a scholarly reexamination of Chinese immigration history. Recent works have examined everything from the lived experiences of the Chinese immigrants who built the Transcontinental Railroad to the vigilante violence white workers in Tacoma, Washington perpetrated against Chinese workers, whom they viewed as economic competition. While great strides have been made in diversifying Chinese immigrant scholarship, historians have left out one small but critical piece of the narrative–Chinese people who lived in the Midwest. In doing so, scholars inadvertently erased the experiences of midwestern Chinese immigrants, ignoring the deep roots they established in the region. Considering renewed interest in both midwestern history and Chinese immigration as a whole, this piece seeks to illuminate the experiences of Chinese immigrants in midwestern communities like Indianapolis.

Chinese Immigration in Indianapolis

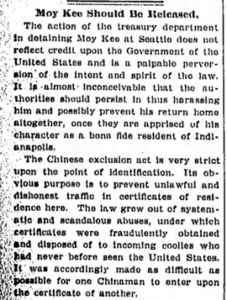

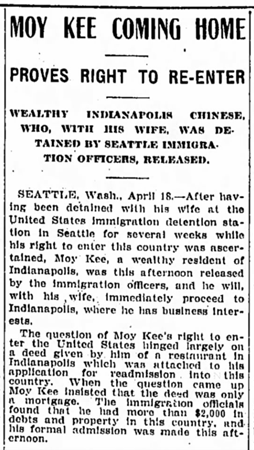

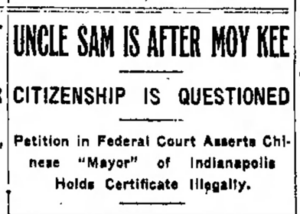

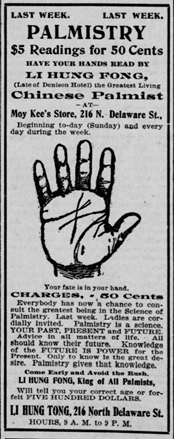

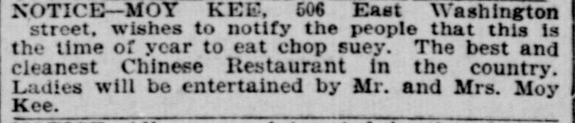

The U.S. Census did not record Chinese residents in Indianapolis until 1880, nearly three decades after Chinese immigrants began settling in the U.S. during the California Gold Rush. The Chinese population in Indiana remained small during the late 19th and early 20th centuries with eighty-nine residents in 1890, 273 in 1910, and 279 in 1930. Most Chinese immigrants in Indiana settled in Indianapolis, but others migrated to Ft. Wayne and Richmond. The 1880 Census recorded approximately ten Chinese residents in Indianapolis, all single men.[1] Despite these small numbers, the Chinese community in Indianapolis received outsized newspaper coverage and attention from the mainstream Hoosier community, with many residents regarding their new neighbors with curiosity. An 1880 edition of the Indianapolis News covered the presence of new Chinese laundries in the city, stating that the presence of Chinese laundryman “has created a decided sensation . . . At any hour of the day crowds are seen gathered in front of laundries watching the Chinese work.”[2] This interest in the nascent Chinese community continued throughout the years and, later, entrepreneurial types, such as restaurant owner Moy Kee, would learn how to leverage the community’s fascination with Chinese culture to their economic benefit.

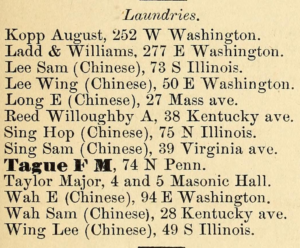

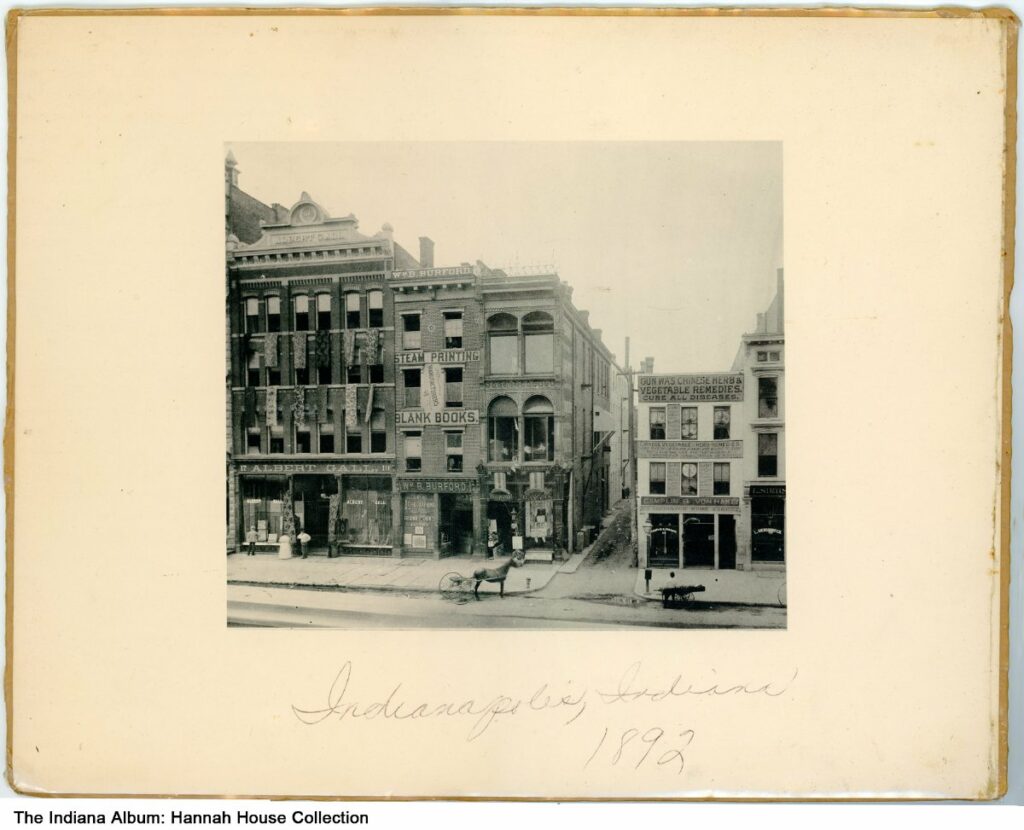

Historian Keith Schoppa noted that for most Chinese immigrants, Indianapolis was a “secondary” settlement, where Chinese people moved after they initially lived in the more populous Chinatowns on the East and West Coasts.[3] It appears many were motivated to move to Indianapolis for economic reasons, with several Chinese residents starting businesses, namely laundries. In 1875, the Indianapolis City Directory recorded two laundries, Sang Lee & Co. on 41 Virginia Avenue and Wah Lee & Co. on Illinois Street.[4] The number of Chinese laundries increased quickly and by 1879, the city directory noted the presence of eight laundries in the city. Notably, the directory also began designating these laundries as “Chinese,” similar to how directories would note if a business was “Black,” and, in doing so, differentiate them from white businesses. The laundries were spread out around the city, along Illinois Street, Washington Street, Mass Avenue, and Kentucky Avenue, indicating the more dispersed nature of the Indianapolis Chinese population.[5]

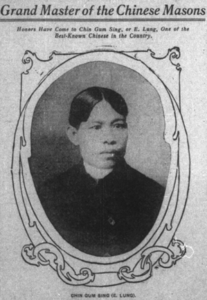

One point to note is the business acumen of the Chinese residents. They advertised their services in mainstream newspapers to attract new patronage, often capitalizing on existing curiosity about Chinese immigrants to build interest in their businesses.[6] Newspapers show that laundrymen across Indiana maintained connections with one another, often working in tandem to ensure their safety and security.[7] Inter-state networks between Chinese businessmen was critical to the welfare of dispersed Chinese immigrant communities like Indianapolis, where residents were bereft of the typical community and connections present in traditional Chinatowns. Businessmen also were cognizant of supply and demand, as demonstrated in the Indianapolis News, which reported that, “The Chinese considering the laundry business overdone in this city [Indianapolis], are talking of sending a colony to Fort Wayne.”[8] This demonstrates that the Chinese business community in Indianapolis not only paid attention to economic conditions in the city, but also actively collaborated with one another to avoid unnecessary competition. These strategies proved effective and many residents, such as Moy Kee, E Lung, and Sam Sing, died with sizeable fortunes and extremely successful businesses.

Overall, it appears that the Chinese community of Indianapolis maintained a nuanced relationship with police and white authority figures. While no mobs or overt hate crimes were committed against the Chinese residents in Indianapolis, they were frequently the target of burglaries at the hands of white assailants. Notably, the victims often reported these incidents to police and worked with authorities to recoup their losses, suggesting a somewhat cooperative relationship between the two groups.[9] However, this cooperative relationship was somewhat tenuous, and white Hoosiers were constantly paranoid about the possibility of Chinese crime or “Tong” activity in Indianapolis. Police frequently placed laundries and restaurants under surveillance due to suspicions of illicit activities. Law enforcement conducted multiple raids on Chinese laundries at night in hopes of finding evidence of gambling and the Chinese betting game Fan-tan.

For example, in January of 1911 approximately twenty Chinese residents appeared in court after being arrested during a police raid while gathering at Quong Lee’s laundry on North Delaware Street. The Indianapolis News covered this event, writing, “Twenty-one unsuspecting Chinese, wearing poker faces, were seated around his [Quong Lee’s] table, yesterday afternoon, when the police appeared … Quong Lee and his ‘guests’ were still deep in their game, among Chinese and American coins and dominoes, when the police suddenly stood among them.” The article noted that the Chinese residents were “respectful” in court and twelve of the men quickly pled guilty and settled their fines with the city.[10] Both the police surveillance and newspaper coverage of possible illicit activity were disproportionate compared to the relative size of the Chinese population. A critical Indianapolis Journal article even categorized the police’s raids a “Chinese Scapegoat,” pointing out that “the police have made no raids recently on the various crap games around the city.”[11]

To be sure, Chinese residents likely gambled and played Fan Tan after work. However, little evidence exists to suggest these activities extended beyond local betting or were connected to a vast Chinese criminal network, as some Hoosiers speculated. Unwarranted concern over illicit activity likely was due to the sensationalized news reporting from Chicago, San Francisco, and other states, which often reached Hoosier ears. The white community’s dual fascination with Chinese culture and mistrust of the intentions of their Chinese neighbors created a difficult environment for Chinese businessmen to navigate. Chinese residents capitalized on their heritage to encourage patronage to their shops but struggled to dispel negative stereotypes about Chinese criminal activity or Hoosier concerns about Chinese gambling.

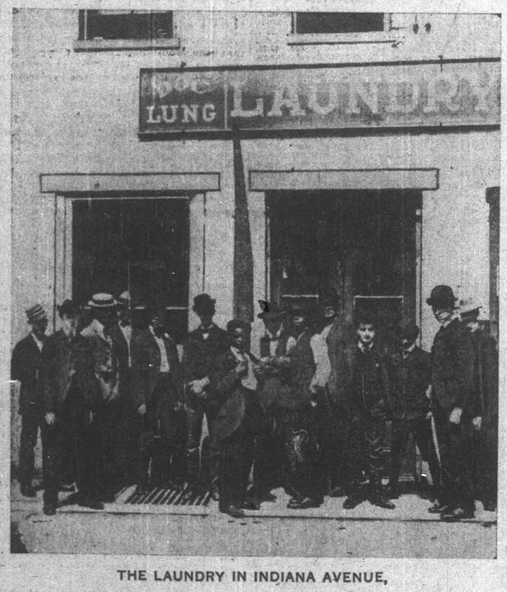

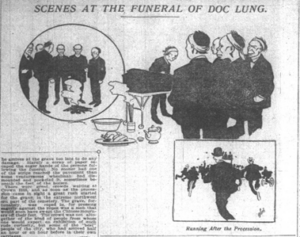

Concerns over criminal activity in the Chinese community peaked in 1902, when a prominent Chinese laundryman, Dong Gon Tshun, colloquially known as Doc Lung, was found murdered at his business on Indiana Avenue. Reporters sensationalized the murder, reporting gory details and speculating on possible criminal activity within the Chinese community. Chin Hee, a Chinese man from Chicago, was quickly arrested for the murder. The murder of Lung pushed Indianapolis into near hysteria, with some residents worrying that the Chinese gang members, often referred to as highbinders, were behind the murder and still active in the city. Doc Lung’s funeral procession was even followed by a curious crowd, which, in other circumstances, could have easily erupted into violence. The murder occurred on Indiana Avenue, where the city’s Black population predominantly lived, and increased tensions between the city’s Chinese community and Black community. Many Chinese residents alleged that a Black assailant, rather than Chin Hee, was responsible for the crime. Chin Hee was ultimately not convicted, and the courts would later convict three Black men for the crime based on dubious evidence.[12]

Ultimately, Doc Lung’s murder case epitomized the tenuous relationship between the Chinese community and white authority figures. Chinese individuals often cooperated with the police and court system, using it to protect their businesses. Police, it appears, were also willing to provide this protection and investigate burglaries or violence against Chinese people in Indianapolis. However, the authorities also regarded the Chinese community with suspicion and paranoia. They speculated that Doc Lung was murdered by highbinders without reasonable evidence and were constantly concerned about Chinese criminal activity permeating into the city. This tension shows that, while Indianapolis residents tolerated Chinese immigrants at a level not seen in coastal states, they never fully accepted them.

Chinese residents also frequently utilized the Marion County court system to settle disputes or advocate for themselves, often successfully. In 1894, a Crawfordsville laundryman named Moy You Bong brought a civil suit against Indianapolis resident Lee Wah over a dispute on the sale of a laundry business in Indianapolis. In response, Lee filed a countersuit denying he defrauded Moy. The court ultimately ruled against Moy, awarding Lee thirty-five dollars.[13] This case of two Chinese residents using the courts to settle a business dispute shows a degree faith in the court system. It also stands in stark contrast to places like California, which actively barred Chinese people from testifying at all.

Conclusion

Chinese laundrymen, restaurant owners, and store owners of Indianapolis achieved relative economic success. They collaborated with one another to ensure their own safety and, in the early years, began experimenting with tying Chinese culture to their business ventures through advertising Chinese goods. Ultimately, the nascent Chinese community in Indianapolis was small, but closely connected and economically astute. Chinese residents utilized the court system and traditional journalism to advocate for their own needs. However, due to unfounded and sensationalized fears over Chinese criminal activity, many were forced to walk a tight line between embracing their culture for economic gain and distancing themselves from their Chinese identity to remain tolerated members of the Indianapolis community.

Historian Anthony J. Miller characterized Chinese immigrants in the Midwest as “pioneers,” who, far removed from Chinatowns, “not only resisted discrimination but were also the first emissaries of their nation to bring cuisine, customs, dress, language, and artwork from their ancestral homeland to states such as Iowa.”[14] While he wrote primarily about Iowan Chinese residents, this characterization too can be applied to Indianapolis’s Chinese population, which displayed resilience and achieved success in the face of discrimination. In doing so, they brought cultural diversity and resources to the Hoosier community. Today, as Americans revisit the “Chinese question,” it is important that scholars expand beyond the coasts and examine a broader spectrum of the Chinese experience. This reveals a narrative not only of exclusion, violence, and discrimination, but also of success, resilience, and community.

For further reading, see:

Joan Hostetler, “Indianapolis Then and Now: Moy Kee Chinese Restaurant, 506 E. Washington Street,” March 21, 2013, accessed Historic Indianapolis.

Kelsey Green, “Moy Kee Part I: The ‘Mayor’ of Indianapolis’s Chinese Community,” Untold Indiana, Indiana Historical Bureau, June 2, 2022, accessed Untold Indiana Blog.

Kelsey Green, “Moy Kee Part II: A Royal Visit,” Untold Indiana, Indiana Historical Bureau, June 27, 2022, accessed Untold Indiana Blog.

Paul Mullins, “The Landscapes of Chinese Immigration in the Circle City,” October 16, 2016, accessed Invisible Indianapolis.

Scott D. Seligman, “The Hoosier of Mandarin,” Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History 23, no. 4 (Fall 2011): 48-55, accessed Digital Images Collection, Indiana Historical Society.

Notes:

[1] Ruth Slevin, “Index to Blacks, Indians, Chinese, Mulattoes in Indiana, 1880 Census,” Genealogy Division, Indiana State Library, Indianapolis.

[2] “Curiosity of Races,” The Indianapolis News, May 21, 1880, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[3] R. Keith Schoppa, “Chinese,” Peopling Indiana: The Ethnic Experience (Indianapolis, Indiana: Indiana Historical Press, 1996), p. 88.

[4]Swartz & Tewdrowe’s Annual Indianapolis City Directory (Indianapolis: Sentinel Company Printers, 1874), p. 464, accessed Internet Archive.

[5] R.L. Polk & Co.’s Indianapolis Directory for 1879 (Indianapolis: R. L. Polk & Co., 1879), p. 540, accessed via Internet Archive.

[6] “Wash List,” Indianapolis News, November 12, 1881; “Wah Lee: A Good Hand Laundry,” Indianapolis Star, December 31, 1923, accessed Newspapers.com.

[7] “Sam Sing Lee’s Funeral,” Indianapolis News, October 30, 1900, accessed Newspapers.com.

[8] “The Chinese,” Indianapolis News, October 29, 1877, accessed Newspapers.com.

[9] “A Chinaman Robbed,” Indianapolis Journal, June 15, 1885; “The Chinese Laundry,” Indianapolis News, May 10, 1880, accessed Newspapers.com.

[10] “12 Chinese Promptly Settle Fan Tan Fines,” Indianapolis News. January 16, 1911, accessed Newspapers.com.

[11] “The Chinese Scapegoat,” Indianapolis Journal, January 31, 1898, accessed Newspapers.com.

For newspaper coverage of other raids on Chinese businesses see: “Get 22 in Fan-Tan Raid,” Indianapolis Star, January 16, 1911, accessed Newspapers.com; “Inquiry to Follow Arrest of Chinese,” Indianapolis Star, May 23, 1915, accessed Newspapers.com; “Pong Tells of High Stakes in Chinese Gaming House,” Indianapolis News, September 21, 1915, accessed Newspapers.com; “Police Find Lid at Slight Angle,” Indianapolis Star, July 2, 1917, accessed Newspapers.com.

[12] “A Chinaman Murdered,” The Indianapolis Journal, May 6, 1902, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Chinese in Court on Murder Charge,” Indianapolis News, May 21, 1902, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Threats on Moy Kee Cause of Commotion,” Indianapolis News, June 11, 1902, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Prisoners’ Lips Sealed,” Indianapolis Journal, March 21, 1903, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[13] “A Cry of Police Falsely Raised,” Indianapolis News, December 22, 1894, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[14] Anthony J. Miller, “Pioneers, Sunday Schoolers, and Laundrymen: Chinese Immigrants in Iowa in the Chinese Exclusion Era, 1870-190,” The Annals of Iowa 81, no. 2 (Spring 2022): 118.