“There has never been a year like 1968, and it is unlikely that there will ever be one again.”–1968: The Year That Rocked the World

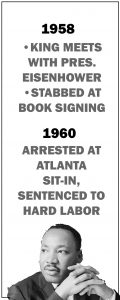

In the very literal sense of the word, 1968 was an extraordinary year. Even situated as it was within a decade characterized by social and political upheaval, 1968 was unique in the sheer number of transformative events: the Tet Offensive, the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy, the Apollo 8 mission, anti-Vietnam War protests, protests against racial discrimination. The list goes on.

While the majority of these events occurred on the East and West Coasts of the United States, it would be a mistake to think that the Midwest was immune to the revolutionary spirit sweeping the nation. In fact, many of the movements seen at a national level played out within the confines of the Indiana University Campus in Bloomington. When recruiters from Dow Chemical Company (the company responsible for producing napalm for use in the Vietnam War) visited campus, hundreds of students marched in protest. Following objections to exclusionary judging standards drawn along color lines, the IU Homecoming Queen pageant was permanently cancelled. African American students demanded more representation in all aspects of campus life and staged a sit-in at the Little 500. That sit-in led directly to the removal of discriminatory covenants from Indiana University’s fraternities.

While this wave of revolutionary fervor was cresting both nationally and on IU’s campus, another wave was close behind – the “third wave” of the Ku Klux Klan. Rising in response to the Civil Rights Movement, approximately 40,000 Klan members belonged to the Klan nationally in the 1950s and 1960s. In the spring of 1968, Klan members from nearby Morgan County attempted to establish a chapter of the terrorist organization in Monroe County. A membership drive, which was to consist of a gathering on the Bloomington courthouse square followed by a march through the business district, was scheduled for March 30, 1968. But before events could get underway, Monroe County Prosecutor Thomas Berry requested and was granted an order blocking the event, citing the possibility of violence.

This was neither the first nor the last appearance of the Klan in Bloomington. In Citizen Klansmen: The Ku Klux Klan in Indiana, 1921-1928, Leonard Moore estimates that 23.8% of all native-born white men in Monroe County were members of the Ku Klux Klan in 1920. The Indiana Daily Student on November 7, 1922 described the supposed first appearance of the Klan in the city:

Marching with slow and solemn tread, 152 men paraded Bloomington streets, garbed in mysterious robes of white, with tall hoods masking their identity, and carrying aloft the flaming cross of the klan, while hundreds of townspeople and students stood and witnessed [as] the pages of fiction and movie scenarios unfolded before their eyes.

Although county officials blocked a similar scene to that described above from playing out in 1968, the Klan still made its presence known in the city. During a Bloomington Human Relations Commission meeting on September 30, 1968, African American commission chairman Ernest Butler showed his fellow commissioners and others present at the meeting a card which had been left on his door. The card read, “The Ku Klux Klan is watching you.” Butler claimed to have received as many as ten such cards, as well as several similarly threatening phone calls. Soon, local Klan affiliates would go further than simply making threats.

In the face of these threats, Black Indiana University students continued to demand more representation and equality, staging protests and demonstrations across the campus. The Afro-Afro-American Student’s Association (AAASA)—an organization formed in the spring of 1968 with the goal of fostering unity among IU’s Black students—frequently encouraged members to participate in this activism. At the forefront of many of these protests was AAASA co-founder and sociology graduate student Clarence “Rollo” Turner.

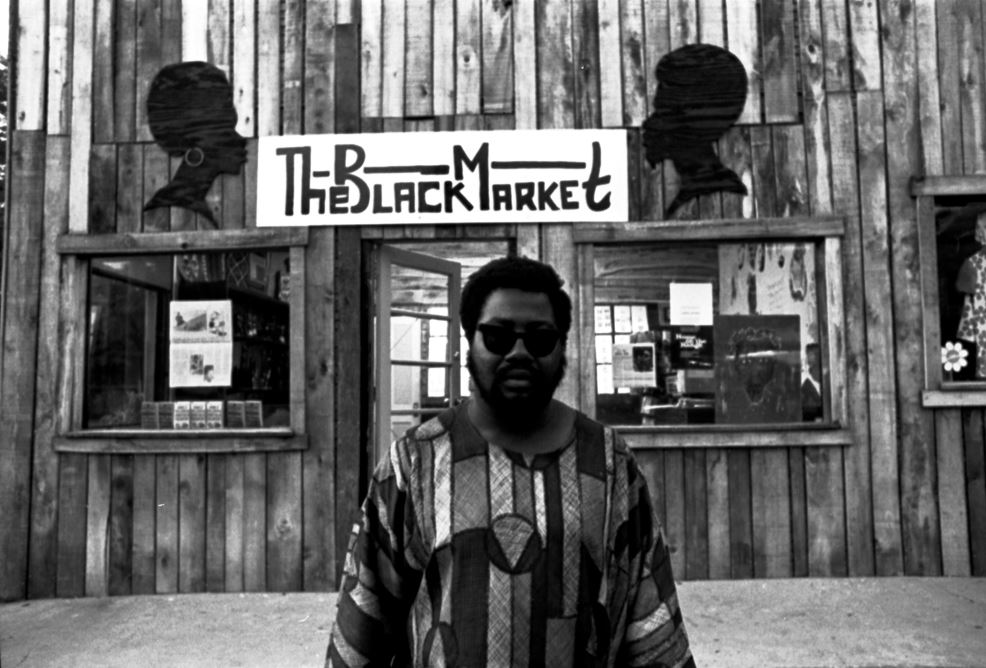

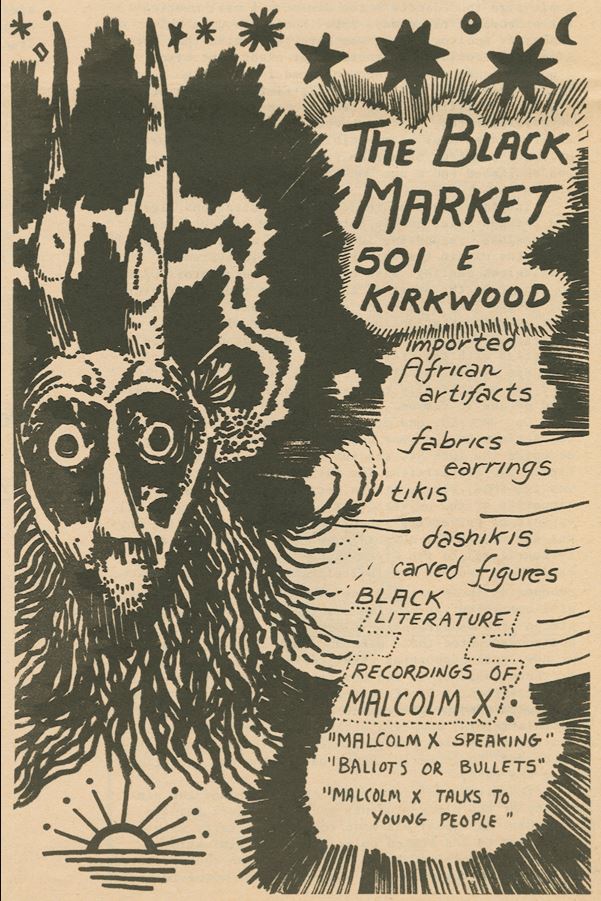

In the fall of 1968, Turner shifted his attention towards a new project – The Black Market. Financed entirely by Black faculty and staff, The Black Market was a shop specializing in products made by African or African American artists. This included “free-flowing African garb, Black literature and records, African and Afro-American fabrics, dangling earrings, and African artifacts.”

As a leader in the African American community at Indiana University, Turner served as the shop’s manager and its public face. He and his backers had two main objectives when opening the shop. First, it was to act as a cultural center for Black students at the university, who had limited recreational opportunities in the predominantly white city. Second, he aimed to eliminate “misconceptions about black people” by exposing IU students and Bloomington locals alike to Black culture.

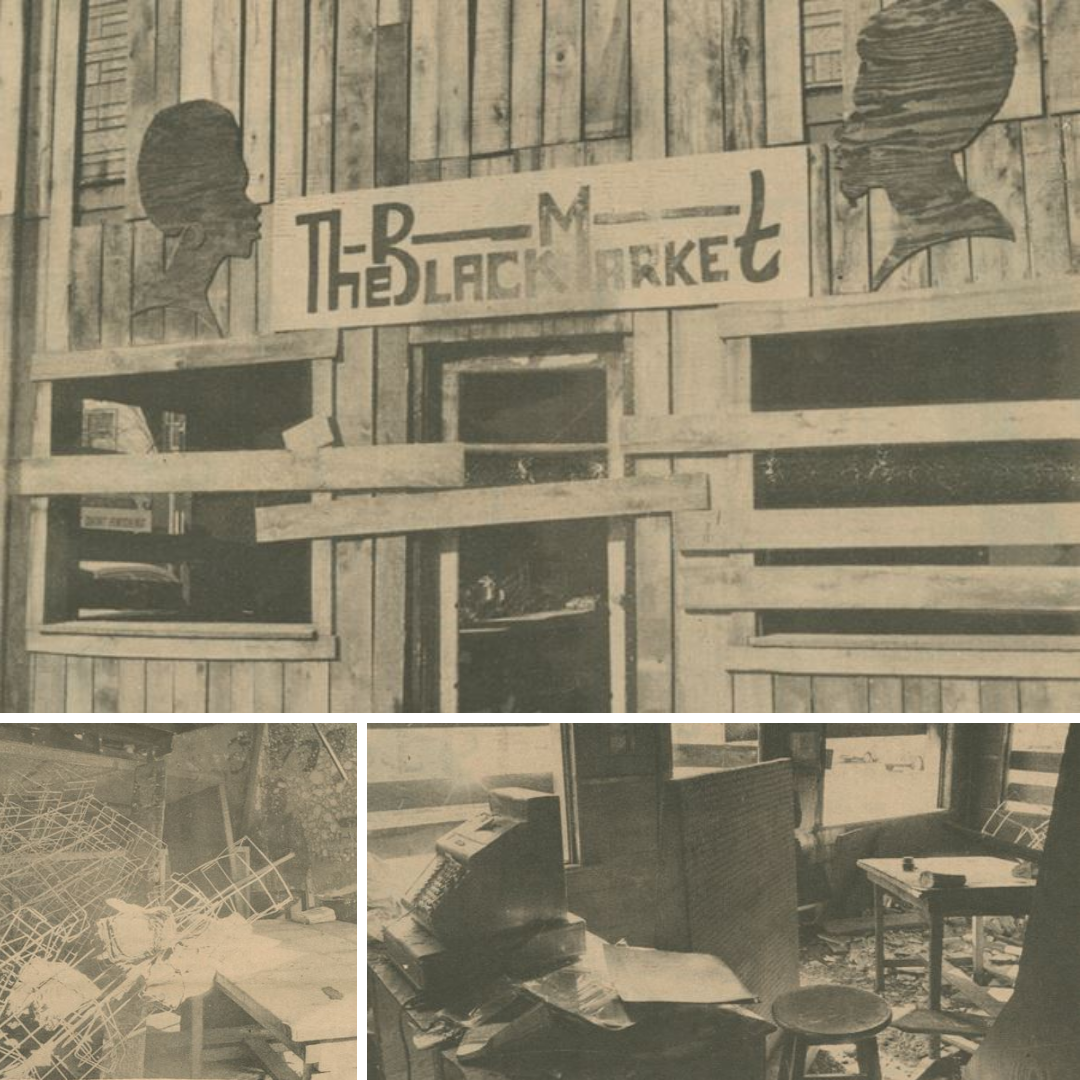

After its late-September opening, it seemed as though the shop would be a success. The campus newspaper, Indiana Daily Student, proclaimed, “suits and ties may eventually join the ranks of white socks and baggy slacks if the immediate success of The Black Market is a sign of things to come.” However, at the same time that the shop was proving a popular enterprise with IU students, factions within Bloomington were pushing back against its very existence. This resistance took the form of violence when, on December 26, 1968 a Molotov cocktail was thrown through the front window of the store.

The resulting fire destroyed the entire stock of The Black Market and caused structural damage to adjacent businesses. To those most closely associated with the shop, the motive for the attack seemed obvious, especially considering the heightened presence of the Ku Klux Klan in the city. As student newspaper The Spectator commented:

It was not very difficult, of course, to determine a ‘motive’ for the bombing. Since the construction of the Black Market in September, black students involved have been harassed periodically by abusive white ‘customers,’ . . . Larry Canada, owner of the building, had received telephoned bomb threads because he allowed the ‘n––rs’ to use the space for the store.

Two weeks later, 200 students attended a rally on the sidewalk outside of the burnt remains of The Black Market. Amidst calls for action from university and city officials and appeals to Black students to make a stand in the face of violence, Rollo Turner said, “the only reason this store was bombed was because it was a black store.” Behind the rally, hung across the splintered door of the shop a hand lettered sign that read, “A COWARD DID THIS.”

Eight months would pass before those students knew the identity of the man responsible for the attack, though. In the intervening time, IU students and faculty came together to raise enough money to pay back the financial backers of the shop, as the shop’s inventory was uninsured. Rollo Turner also made the decision not to re-open the store – all of the funds raised had gone to pay back investors, leaving none for re-investment in new stock. Additionally, the extensive damage to the structure necessitated its total demolition, meaning a new space would need to be secured and it may have proven difficult to find a landlord willing to risk their property if a repeat attack was carried out.

Details about the search for the perpetrators are limited. An ad-hoc group formed by representatives from the community, university, and local civil rights organizations offered an award for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the guilty parties. The alternative student newspaper The Spectator alluded to a person of interest in their coverage of the attack, saying:

Acting on reports of witnesses, police are searching for a white male with dark hair, about 5’8”, 160 lbs., wearing a light gray finger-length topcoat at the time of the fire.

Whether or not either of these played any part in the search for the perpetrators, or if they were identified in some other way, on August 6, 1969 the Marion County Circuit Court issued arrest warrants for two men in relation to the crime. One of those men, Carlisle Briscoe, Jr., plead guilty to the second degree arson charges while implicating as an accomplice Jackie Dale Kinser, whom he accused of driving the get-away vehicle. Eventually, the charges against Kinser would be dropped, just before he plead guilty to three unrelated crimes.

Both men had strong ties to the local Ku Klux Klan – Kinser was a member who in subsequent years would be arrested multiple times in Klan-related crimes. Briscoe’s Klan connections are slightly less clear. At first, Monroe County Prosecutor Thomas Berry and Sheriff Clifford Thrasher announced that both men were Klan members. An article in the September 19, 1969 issue of the Indianapolis Star, states that Briscoe himself claimed to be a Klan member. The headline of Briscoe’s obituary in the Vincennes Sun-Commercial proclaims, “Notorious Klansman Dies in Prison: Briscoe Led a Bloomington Crime Wave in 1960s and ‘70s.” As late as 1977, he was arrested while committing crimes alongside Klan members, apparently while carrying out Klan business. However, in 1969, the Grand Dragon of the Indiana Ku Klux Klan, William Chaney, denied that Briscoe was a member of the organization. Regardless of Briscoe’s official Klan membership status, Briscoe at the very least maintained close ties with the terrorist organization. He was sentenced to one to ten years and was released on April 7, 1973 after serving approximately three and a half years of his sentence.

The story of The Black Market firebombing could have ended there. The structure had been demolished, the investors had been paid back, and a conviction had been made. However, the revolutionary atmosphere on the Indiana University campus stretched beyond the 1960s, and the space would once again be used to make a statement.

In late February 1970, a group of Yippies, or members of the Youth International Party, were looking for ways to bring the community of Bloomington together. One of the ideas that emerged from these discussions was the creation of a people’s park on the vacant lot where The Black Market had once stood. People’s parks, which were spreading across the nation, could trace their roots back to the People’s Park in Berkeley, California. Typically created by activists without the approval of government or other officials, the parks were meant to promote free speech, activism, and community involvement.

By May 1970, work had started on the project. Anyone who was interested in the enterprise was encouraged to join in helping to prepare the land for its future intended use. The Bloomington People’s Park was to be a mix of gathering space, community garden, and a place for “everyone to sing, dance, rap, and generally ‘do his own thing,’” and by the next summer, it was being put to good use, as reported by the Indiana Daily Student:

About 250 blue jeaned “freaks,” tapered-legged “straights,” the bell bottomed curious and two guys with rolled-up sleeves, greasy hair and tattoos celebrated the 4th in People’s Park Sunday evening.

Over the next five years, various issues threatened to put an end to the whole affair. The city threatened to shut it down over “public health” concerns. The property owner, Larry Canada, had various plans to develop the property. In the end, though, People’s Park became legally sanctioned after Canada deeded the land to the city in 1976.

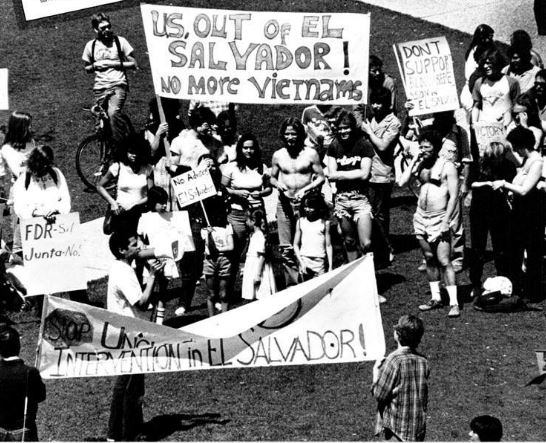

Throughout the years, the park has carried on the site’s democratic heritage, hosting anti-Vietnam War protests, protests against the US involvement in El Salvador in the 1980s, music festivals, flea markets, and, more recently, Occupy Bloomington protests. Today, the park serves as a reminder of the revolutionary ideals that swept through Indiana University’s campus in the 1960s and 1970s. In 2020, IHB, in partnership with the Bloomington Chamber of Commerce, will commemorate those events by installing an Indiana state historical marker.

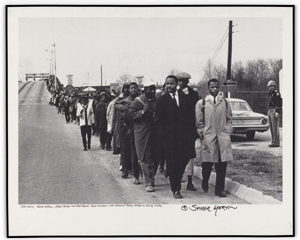

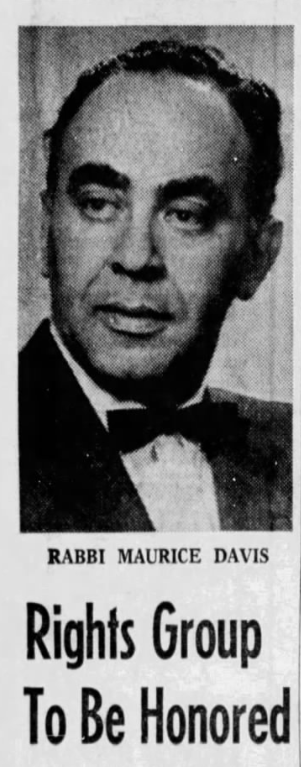

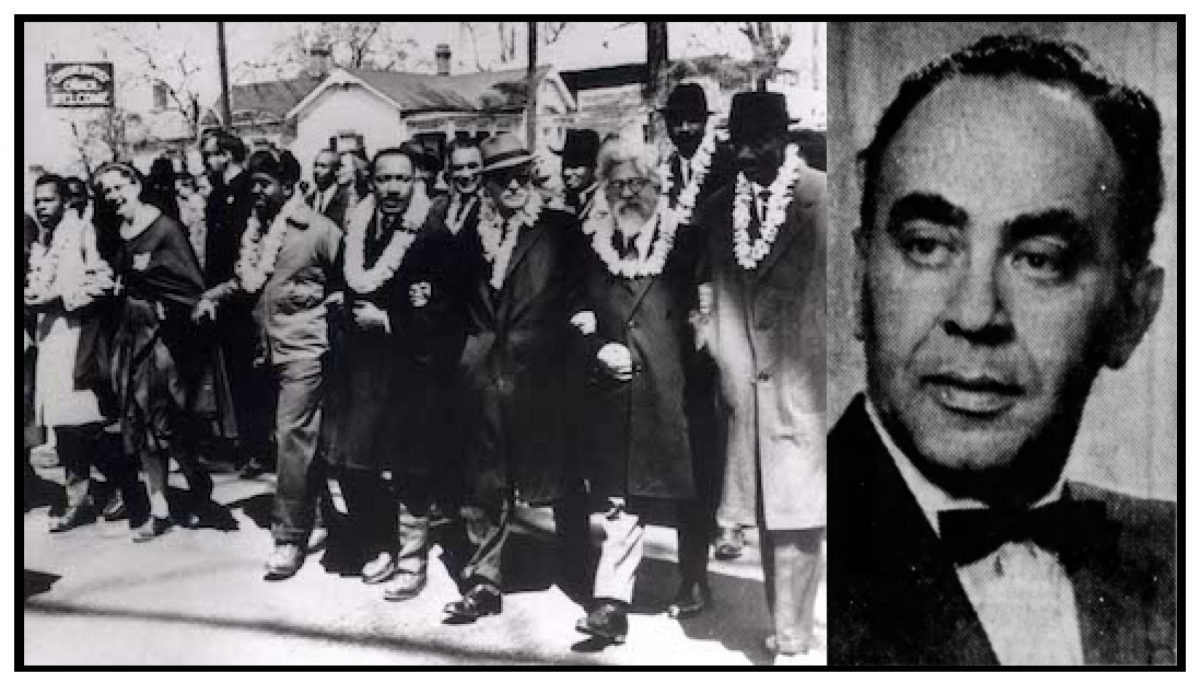

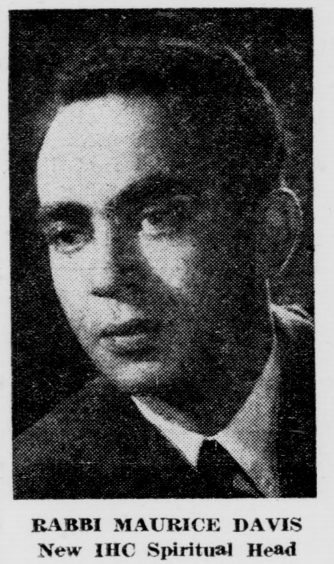

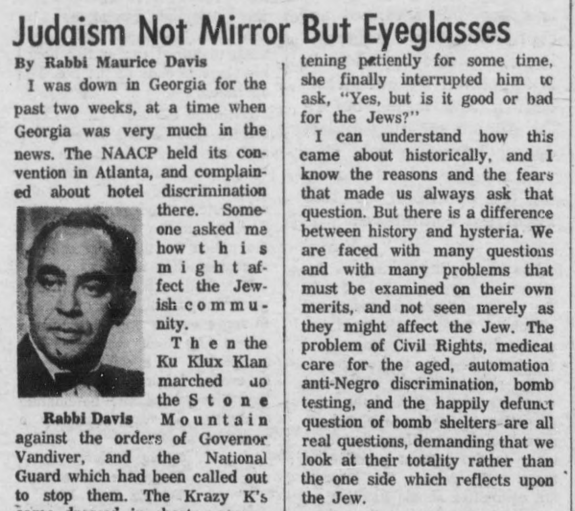

Maurice Davis was born in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1921. Census records show that his Russian-born father Jacob managed a garage while his mother Sadie cared for five children. They did well for themselves and were able to send Maurice first to Brown University in 1939 and then to the University of Cincinnati where he received his B.A. in 1945. He then received his Master of Hebrew Letters from the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. After serving several different congregations as a student rabbi, he became rabbi of Adath Israel in Lexington, Kentucky in 1951. By this point he was already active in the local civil rights movement and joined the Kentucky Commission Against Segregation.

Maurice Davis was born in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1921. Census records show that his Russian-born father Jacob managed a garage while his mother Sadie cared for five children. They did well for themselves and were able to send Maurice first to Brown University in 1939 and then to the University of Cincinnati where he received his B.A. in 1945. He then received his Master of Hebrew Letters from the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. After serving several different congregations as a student rabbi, he became rabbi of Adath Israel in Lexington, Kentucky in 1951. By this point he was already active in the local civil rights movement and joined the Kentucky Commission Against Segregation.

Rabbi Maurice Davis became the spiritual leader of the

Rabbi Maurice Davis became the spiritual leader of the

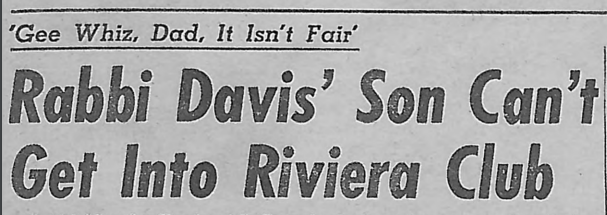

Rabbi Davis not only advocated for equality for Jews, but all people facing oppression. He encouraged Jews to look beyond their own community and work to end discrimination everywhere. He stated, “A decent and sensitive America is good for all Americans and we must help her be so” (

Rabbi Davis not only advocated for equality for Jews, but all people facing oppression. He encouraged Jews to look beyond their own community and work to end discrimination everywhere. He stated, “A decent and sensitive America is good for all Americans and we must help her be so” (

His columns were often fiery calls to action. For example, in September 1963, he

His columns were often fiery calls to action. For example, in September 1963, he