This video was originally published on the Hoosier State Chronicles blog.

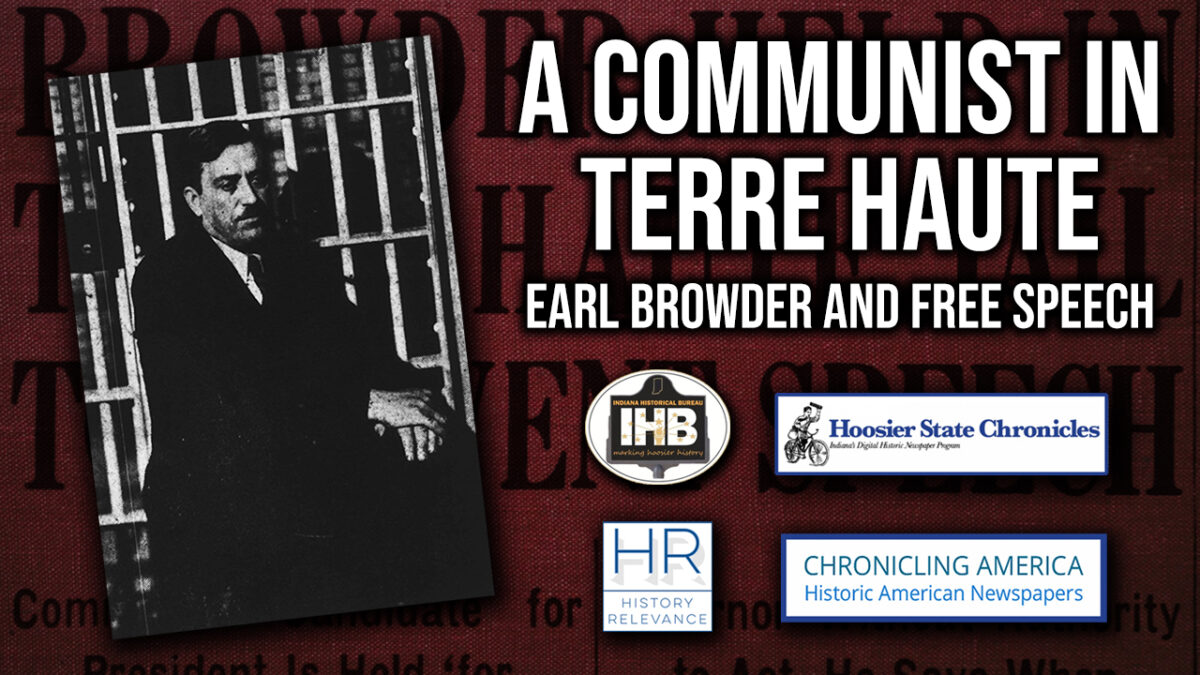

Five men are sitting in a jail cell in Terre Haute, Indiana. The leader of the group—a middle-aged, mustached, and unassuming figure—had been arrested on charges of “vagrancy and ‘for investigation’,” according to the local police chief. But it wasn’t a drunk or an unlucky drifter sitting in the cell. It was the leader of an American political party and its nominee for President of the United States. He had tried to give a speech in Terre Haute when arrested by the local authorities. His case became a statewide and even national discussion on the importance and limits of free speech. Now, who could’ve caused all of this ruckus? It was Earl Browder, General Secretary of the Communist Party of the United States.

Learn more Indiana History from the IHB: http://www.in.gov/history/

Search historic newspaper pages at Hoosier State Chronicles: www.hoosierstatechronicles.org

Visit our Blog: https://blog.newspapers.library.in.gov/

Visit Chronicling America to read more first drafts of history: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/

Learn more about the history relevance campaign at https://www.historyrelevance.com/.

Please comment, like, and subscribe!

Credits:

Written and produced by Justin Clark.

Music: “And Then She Left” by Kinoton, “Echo Sclavi” by the Mini Vandals, “Namaste” by Audionautix, “Myositis” by the United States Marine Band, “Finding the Balance” by Kevin MacLeod, and “Dana” by Vibe Tracks