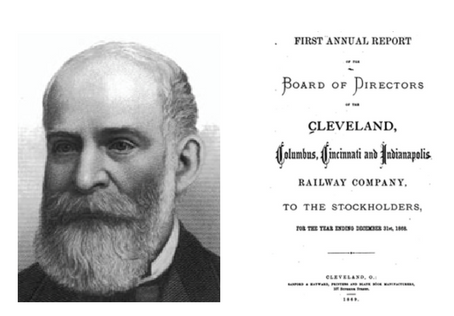

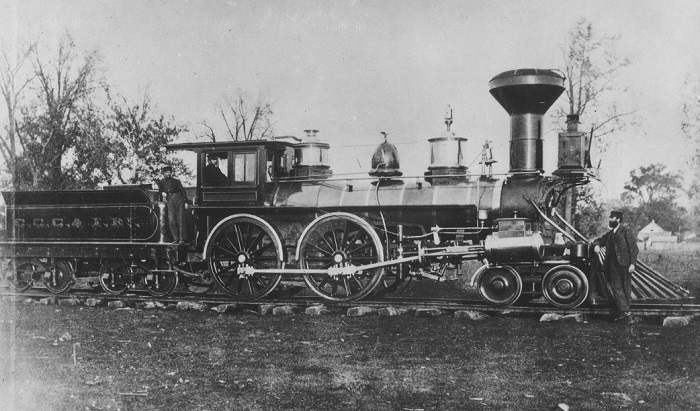

On December 5th 1868, a home gas stove explosion nearly killed and “terribly burned” longtime Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati Railroad (CC&C) president, Leander M. Hubby. For more than a decade Hubby had led this regional powerhouse as it solidified its financial grip on the Bee Line component railroads. Along the way, he earned an almost patriarchal reputation among officers and men of the road’s operating corps.

In May 1868 Hubby had assumed the presidency of the successor railroad that, for the first time, combined the Bee Line components roads into a single legal entity: the Cleveland, Columbus, Cincinnati and Indianapolis Railway (CCC&I). Unfortunately, his near-death experience effectively sidelined Hubby until he officially resigned his role in September 1870.

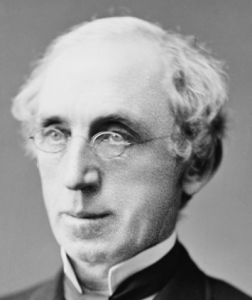

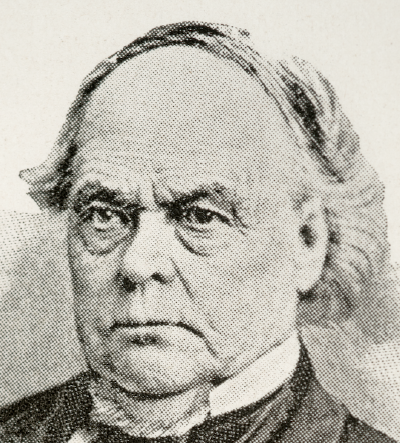

Into this leadership vacuum stepped a new duo of recently ensconced Bee Line board members. Oscar Townsend’s board appointment in September 1868 closely followed Hinman B. Hurlbut’s similar election at the formation of the CCC&I that May. Then, following Hubby’s unfortunate accident and subsequent resignation in 1870, the Townsend/Hurlbut duo formally assumed their heretofore-tacit responsibilities as president and vice president. They could not have written a more perfect script.

Hurlbut had joined the Bellefontaine Railway’s board and finance committee at its formation in 1864. His Cleveland-centric banking business included numerous Cleveland Clique clients. Soon he was part of the group. Hurlbut had purchased the charter of Cleveland’s Bank of Commerce in the 1850s and reorganized it as the Second National Bank.

Oscar Townsend began his career with the CC&C as a laborer in 1848. Between 1856 and 1862 he advanced through the ranks of its Cleveland freight office. Townsend shifted to Hurlbut’s Second National Bank in 1862, learning his banking skills at Hurlbut’s knee.

The CC&C’s longstanding general ticket agent S. F. Pierson reported, in an exposé on the demise of the railroad, that Hurlbut had tapped the bank of its financial strength by the time he left it in 1865. While one flattering biographer characterized Hurlbut’s exit as due to “the arduous labors and close application necessitated by these and other financial tasks he had undertaken,” Pierson had a different take.

From Pierson’s perspective, Hurlbut “retired, consequent upon the destruction of more than its [the Second National Bank’s] entire surplus, and some of the securities and private deposits of the Bank. These…had been abstracted, and the money lost in speculation. The cashier had ended his own life in a painfully tragic manner, and Mr. Hurlbut was permitted to retire.”

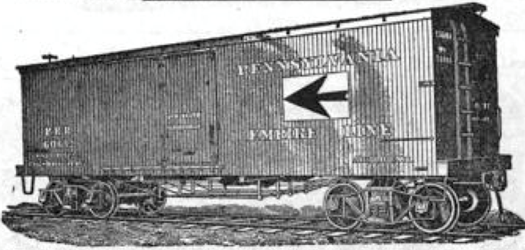

It was about this time that Oscar Townsend also left the bank and segued to a superintendent’s role overseeing the Western Department of the Empire Transportation Company. Such businesses were immensely profitable and important extensions of the railroads they served in the post-Civil War era. Responsible for developing relationships with key shippers, businesses such as the Empire Line “fast freight” often decided which railroads would transport the huge amounts of freight under their control.

At the same time, nearly all railroad presidents quizzed by an 1867 Ohio Special Legislative Committee confessed they had been offered fast freight line stock “on favorable terms, or as a gratuity.” Enticed railroad directors began to work in concert with the “fast freights” to direct high-value freight traffic over their favored “fast freight”. This left only bulkier and less profitable local freight for the railroads themselves.

Inasmuch as the CCC&I started life in 1868 as a “financiers” railroad, Townsend and Hurlbut fit right in. By the time of Hubby’s retirement in 1870, they took control.

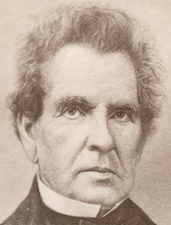

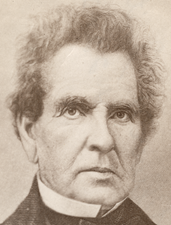

In the Bee Line’s new form, an old and wily politician to handle the Hoosier “good old boy” network was no longer needed. The long railroad career of David Kilgore came to an end in February 1870. And with his departure went the last vestige of the Hoosier Partisans.

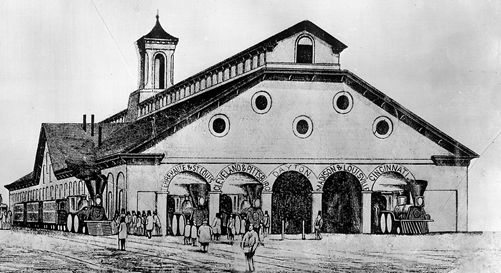

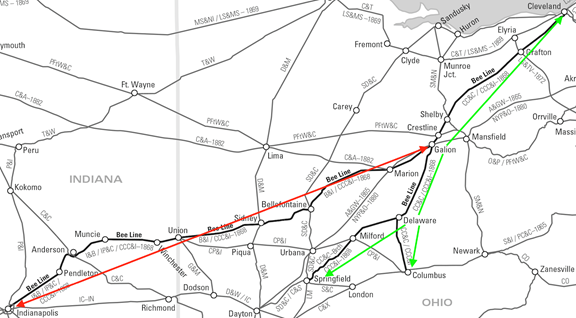

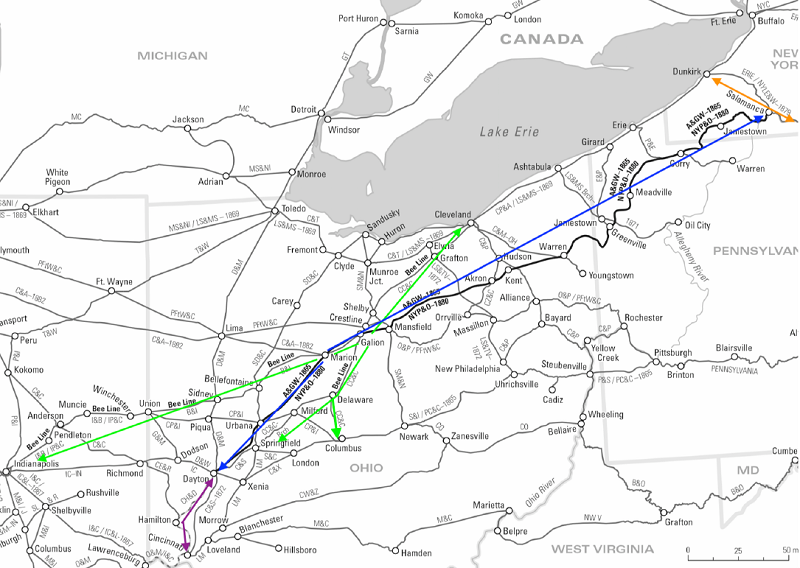

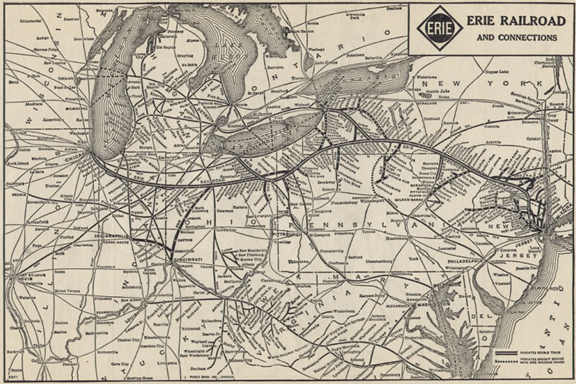

Only one significant transregional railroad would be constructed during the Civil War. The amalgam of railroads that became known as The Atlantic and Great Western Railway Company (A&GW) would stand by itself. With huge capital infusions from London and Continental investors, the road opened for business in August 1865 along its entire 388 mile route from Salamanca in Upstate New York to Dayton Ohio.

Nefarious London rail broker-cum-financier James McHenry had cajoled voracious English and European investors to fund the improbable A&GW project. Exploiting his role as proxy for these complacent capitalists, McHenry seized control of the road Ohioan Marvin Kent had brought to life in the 1850s. And by the early 1870s, he also commandeered the board of the Eastern trunk line intersecting with the A&GW at Salamanca: The Erie Railway. Now, he needed an outlet to St. Louis to complete his domination of railroads extending from New York City to the West.

James McHenry’s financial flimflam with A&GW’s European investors always left free cash with which to subsidize his own schemes. He had used some of those funds to insert Peter H. Watson as president of the Erie Railway in 1872. Watson became McHenry’s conduit to Hinman B. Hurlbut and the Bee Line. McHenry would sprinkle a substantial amount of cash on Hurlbut, and their subterfuge to assume control of the CCC&I.

Within weeks of Watson’s elevation to Erie’s presidency, he penned a letter to McHenry:

I opened negotiations with the parties controlling this road [CCC&I], and my success was greater and more rapid than I could have hoped. The result is embraced in the conditional agreement made by you with Mr. Hurlbut.

Hurlbut convinced members of the Cleveland Clique to sell their shares before word of an impending takeover became public. He then conveyed the acquired shares, and others from the Bee Line treasury, to McHenry. As S. F. Pierson noted:

…several members [of the CCC&I board] were …retired from active pursuits, and not disposed to take much trouble in the matter; and of the balance, one portion used the Vice-President [Hurlbut] to further some scheme of their own, and the other hoped he might want to use them.

When the A&GW’s plans for the CCC&I became public in early 1873, members of the Cleveland business establishment and other New York investors were completely flummoxed. After all, the A&GW showed assets of less than $40 million while reporting liabilities of more than $120 million. By comparison, the CCC&I was of robust but declining financial health. S. F. Pierson was stunned, noting, “Vice President [Hurlbut] has unbolted our doors from within.”

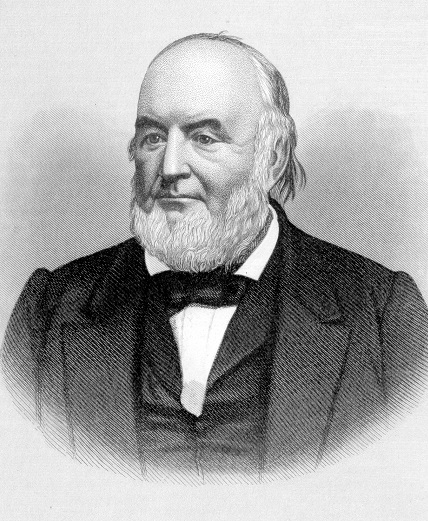

John H. Devereux, soon to become a key player in the final destiny of the Bee Line, painted a more colorful picture. He characterized the possibility as “an attempt to chain a living man to a dead corpse.” Before long, as orchestrated by James McHenry, Devereux would become President of both the Bee Line and the A&GW, and vice president at the Erie – all at the same time!!

McHenry had arranged for Devereux’s CCC&I presidential appointment as soon as the A&GW assumed financial and board control of it in April 1873. Devereux’s installation quelled some of the Bee Line stockholders’ angst, given his upstanding reputation as a railroad executive. But when Ohio’s legislature blocked McHenry’s plan to lease the CCC&I to the anemic A&GW, the Bee Line shareholders’ attitude shifted.

Still seeking to run the A&GW and CCC&I as a single entity in spite of his failed leasing scheme, McHenry orchestrated Devereux’s appointment as general manager at the A&GW. By January 1874 he was bumped up a notch to president – while still heading the rival Bee Line!

The Bee Line shareholders had had enough. In an effort to oust McHenry’s A&GW and Erie board proxies, they orchestrated a massive CCC&I shareholder turnout for the March 1874 annual meeting. The opposition candidate slate included several former Cleveland Clique members, New York investors, and one Hoosier: David Kilgore.

And in an interesting twist, deposed CCC&I president Oscar Townsend headed the opposition – until Hinman Hurlbut brought to light Townsend’s involvement in a freight payola ring. The revelation tipped the balance. The opposition suffered a narrow defeat. There would be no Hoosier Partisan revival.

Longer term, James McHenry’s self-induced financial problems would only mount. His tenuous grip on the A&GW and CCC&I slipped away at the hands of Peter Watson’s 1874 Erie Railway successor: Hugh H. Jewett. Jewett would extricate the Erie from McHenry’s grasp, and push him to near-bankruptcy.

John Devereux remained president of both the Bee Line and A&GW (exiting bankruptcy as the New York, Pennsylvania and Ohio Railroad [NYPA&O; Nypano]) until 1881. At that time William H. Vanderbilt, of New York Central Railroad fame, sought control of the Bee Line to assure an entry into Cincinnati and St. Louis. Devereux had taken control of the linchpin to Cincinnati: the Cincinnati, Hamilton and Dayton Railroad. He soon yielded to Vanderbilt’s advances.

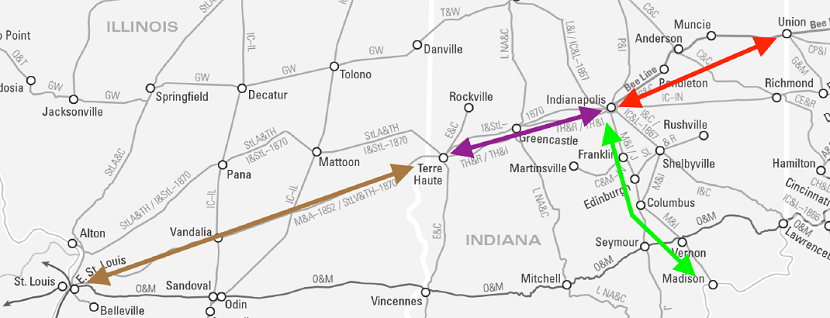

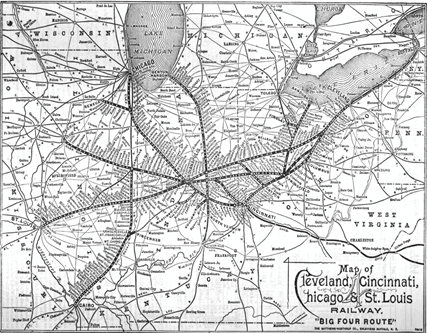

By 1889 the Bee Line and the Indianapolis and St. Louis Railroad it controlled (between Indianapolis and St. Louis) would be folded into another Vanderbilt-controlled railroad and emerge as the Big Four route.

In making this decision Devereux, in his role as president of the NYPA&O, effectively parted ways with a livid Hugh Jewett and the Erie. A week later Devereux resigned. Soon, the Erie would subsume the NYPA&O.

The die was now cast for the future of the Bee Line as well. Its destiny would lie with Vanderbilt’s New York Central.

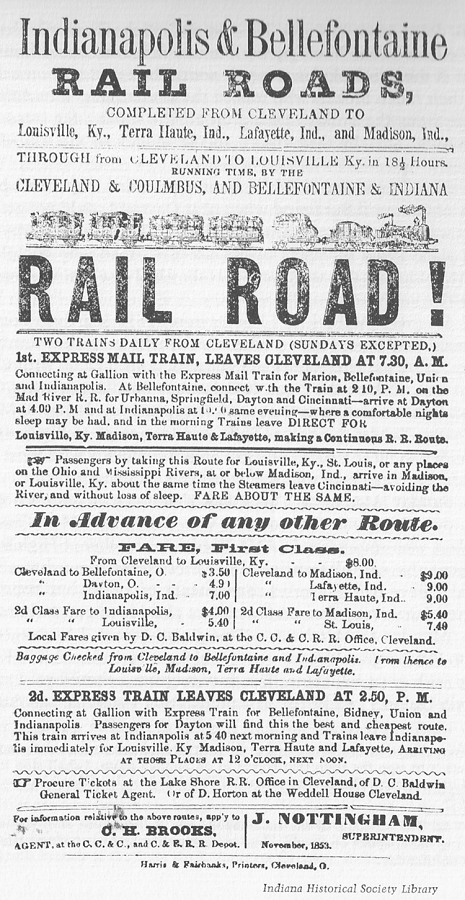

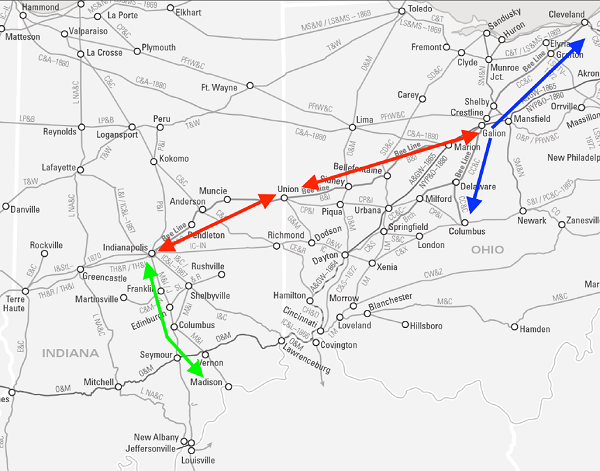

It had been a long journey since 1848, when Oliver H. Smith challenged the citizens of east central Indiana to avoid being bypassed by the technological marvel of the age. They would heed his warning by their investment in the Indianapolis and Bellefontaine Railroad – the Bee Line’s Indiana segment.

Smith’s prescient vision proved to be uncannily accurate. It was if he had penned Indiana’s state motto: “the Crossroads of America.” But for the Bee Line, it might never have come to pass.

Interested in the Bee Line?

![Midwest Railroads Map, circa 1860, showing the Madison and Indianapolis [M&I], Terre Haute and Richmond [TH&R], and component roads of the Bee Line: Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati [CC&C]; Bellefontaine and Indiana [B&I]; Indianapolis and Bellefontaine](http://blog.history.in.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Midwest-Railroads-Map-c1860.png)

![Railroads west from Indiana, including the Terre Haute and Richmond [TH&R], Ohio and Mississippi [O&M], Mississippi and Atlantic [M&A], and St. Louis, Alton and Terre Haute [StLA&TH]](http://blog.history.in.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Railroads-West.png)

![image of The Madison and Indianapolis Railroad [M&I] and involved roads: the Peru and Indianapolis Railroad [P&I], extending north from Indianapolis, and the Mississippi and Atlantic Railroad [M&A], extending west to St. Louis. Terre Haute and Richmond [TH&R]](http://blog.history.in.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/MI.png)