William Dudley Pelley tapped into a small, but growing contingent of Americans who admired Hitler’s fascist agenda, particularly his oppression of the Jewish population. With the formation of the Silver Shirts in 1933, Pelley not only cultivated a degree of power and influence, but amassed a small fortune through his “‘fanatical and misled followers.'”[1] Using his North Carolina printing press, the “little Fuehrer” disseminated fascist tenets and groomed a Christian-based militia, with the goal of overthrowing the American government.[2] Throughout his life, Pelley spun together political ideologies and spiritual dogmas to suit his needs.

After evading serious punishment following a House Committee to Investigate Un-American Activities hearing, he transferred his operation to Noblesville, Indiana in 1940. There, he established the Fellowship Press with the assistance of former state policeman and Klan leader Carl Losey. However, the men underestimated the resistance they would encounter in the conservative Indiana town, already humming with the manufacture of war munitions.

Hoosiers hotly rejected Pelley’s extremist propaganda. Their resistance, along with congressional investigations and consistent local media reporting, helped stamp out the efforts of “America’s No. 1 seditionist,” who posed a tangible threat to America’s national security during a period of global unrest.

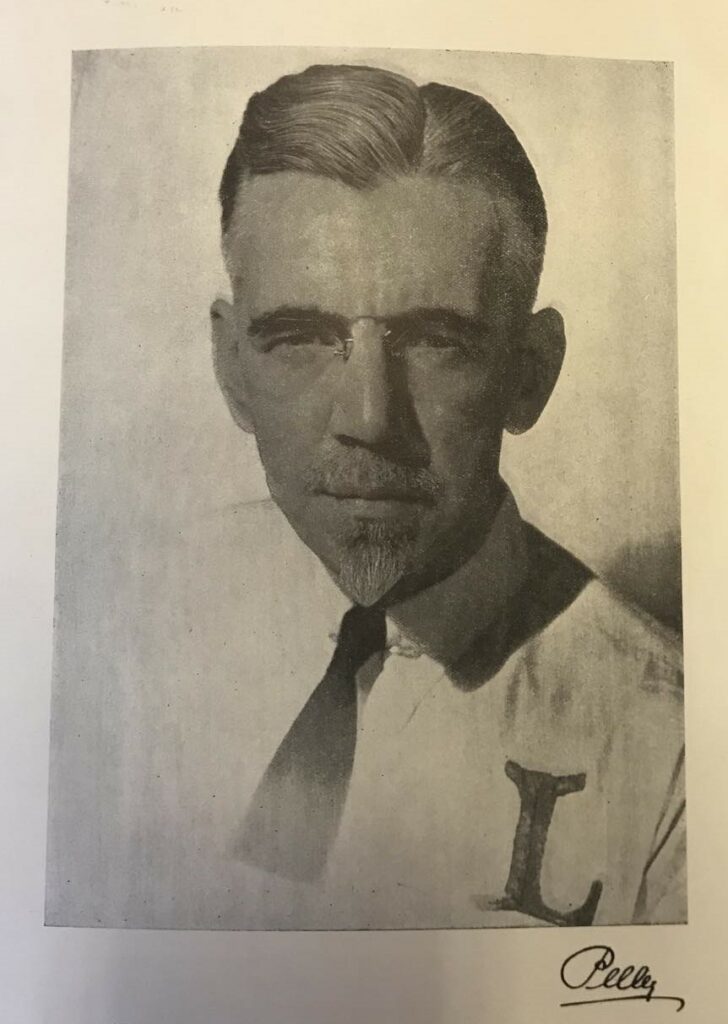

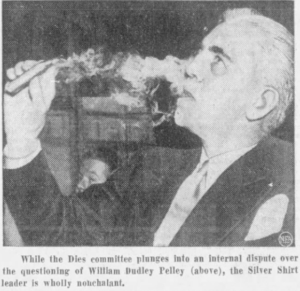

The son of a Methodist minister, William Dudley Pelley was born in 1890 in Massachusetts, where he developed an affinity for the written language. According to Jason Daley’s Smithsonian Magazine article, Pelley wrote prolifically in his youth and by the age of 19 had developed “ideas about how Christianity would have to morph if it were to survive in the modern world.”[3] He quickly parlayed his literary skills into a career, writing short stories for publications like the Saturday Evening Post, Washington, D.C.’s Sunday Star, and Red Book Magazine.[4] Pelley experienced some success as a script writer in Hollywood, where he likely learned the value of image. He employed his trademark goatee, bespoke suits, and plume of cigarette smoke to project an air of poise and authority. Through his persona, Pelley convinced others that he was a visionary, quite literally.

In 1929, Pelley detailed an existential experience in his American Magazine article, “Seven Minutes in Eternity—the Amazing Experience that Made Me Over.”[5] He claimed he had communed with spirits and even Jesus Christ himself. Perhaps the instability of the early Great Depression years attracted some Americans to the man who claimed to possess answers about the future. By 1931, Pelley garnered enough support that he was able to move to Asheville, North Carolina, where he opened a publishing company.[6] Initially focused on metaphysical topics, he pivoted to right-wing fringe issues via publications like The New Liberator (later Liberation).

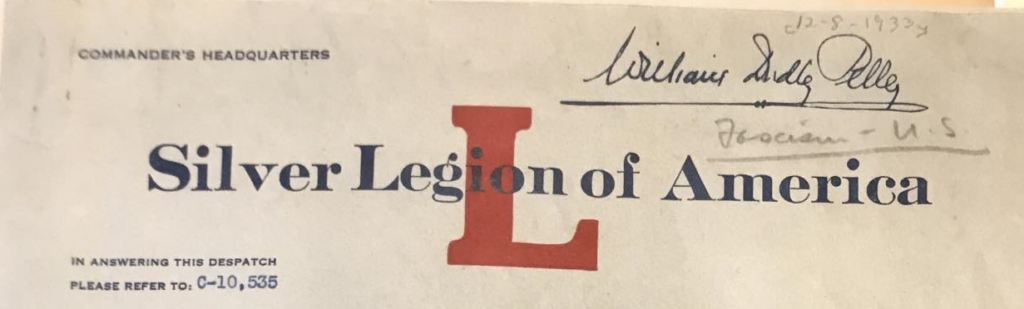

According to WNC Magazine, in 1933—the year Hitler was appointed Chancellor of Germany—Pelley put these ideals into practice by forming the Silver Legion of America. Better known as the Silver Shirts, Pelley envisioned the group to operate as a “‘Gentile American Militia.'”[7] The Silver Shirts emulated Hitler’s Sturmabteilung (the “Brown Shirts”) paramilitary organization, as uniformed Legion members quietly mobilized across the country in defense of racial purity. They were guided by Pelley’s alarmist publications, which espoused a mosaic of “isms,” including isolationism, anti-Communism, and, most staunchly, anti-Semitism. The New Republic described his ideology as “‘a mad hodgepodge of mystic twaddle and reactionary, chauvinistic demagogy.'”[8]

Pelley’s publications not only drew the attention of a congressional committee that investigated un-American activities, but ultimately led to his arrest for financial crimes.[9] Perhaps these charges were unsurprising, considering members had to divulge their income, banking institution, and real estate holdings on their membership questionnaire.[10] In 1935, a jury found Pelley guilty of violating North Carolina’s “Blue Sky” laws after he misrepresented the value of Galahad Press’s stock. In other words, he bilked investors for personal gain.[11] However, Pelley managed to avoid prison time after agreeing to a set of conditions, which included “good behavior for five years.” Such probation terms would prove difficult for a man of his temperament.

In fact, his legal woes and notoriety seemed only to embolden Pelley. Just months after his sentencing, Pelley announced his candidacy for president via the national Christian party, running on the platform of “Christ and the Constitution.”[12] His ill-fated run garnered less than 2,000 votes. As he had many times, Pelley didn’t dwell on the loss and instead shifted focus. He turned his attention back towards expanding the Silver Shirt Legion.

According to the Legion’s handbook, entitled One Million Silver Shirts by 1939, the group sought to make it illegal for American Jews to own property in “‘any city but one in each state.'”[13] The handbook also proposed dismantling President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal programs. It called for the repeal of congressional measures enacted to bolster the depressed economy, such as the Social Security Act and National Labor Relations Board. And, Pelley instructed his 25,000 followers, if doing so “‘meant force it meant force.'”[14] According to Daley’s Smithsonian piece, in 1938, the organization “began a big membership push and started showing signs that it was moving towards violence.”[15]

Indeed, National Guard officer and ENT specialist Dr. Samuel Rubley, of Logansport, Indiana, later testified that he requested the Silver Shirts dispatch him to Detroit.[16] There, he reportedly mobilized a Legion “cavalry,” tapping into the growing Klan presence in the region. Dr. Rubley taught classes like horsemanship to Klansman, as well as reserve officers and their wives. These efforts were undertaken, he said cryptically, in an effort to prepare to “‘defend their homes.'” He anticipated that “the snows would be dyed red in Detroit,” as the nation would again be at Civil War over clashing political ideologies. Dr. Rubley admitted later that he had been “listening too much to ‘alarmists'” and “‘became inflamed for a while until it became a little too fantastic.'”[17]

Dr. Rubley’s statements certainly lent credence to the sentiments of an unnamed columnist in the Indiana Bremen Enquirer, who wrote:

that Mr. Pelley should be able to muster a group of followers calling themselves Americans, who had so little understanding of the fundamental basis of Americanism, is a sorry commentary upon the intelligence and understanding of a considerable sector of the American people.[18]

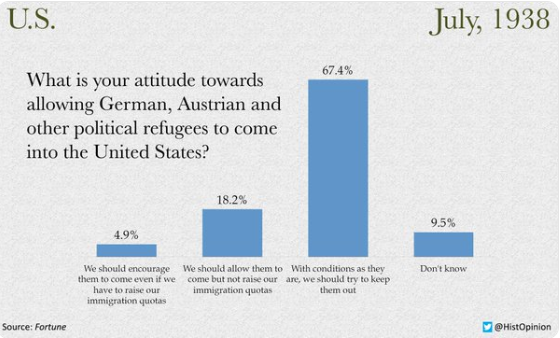

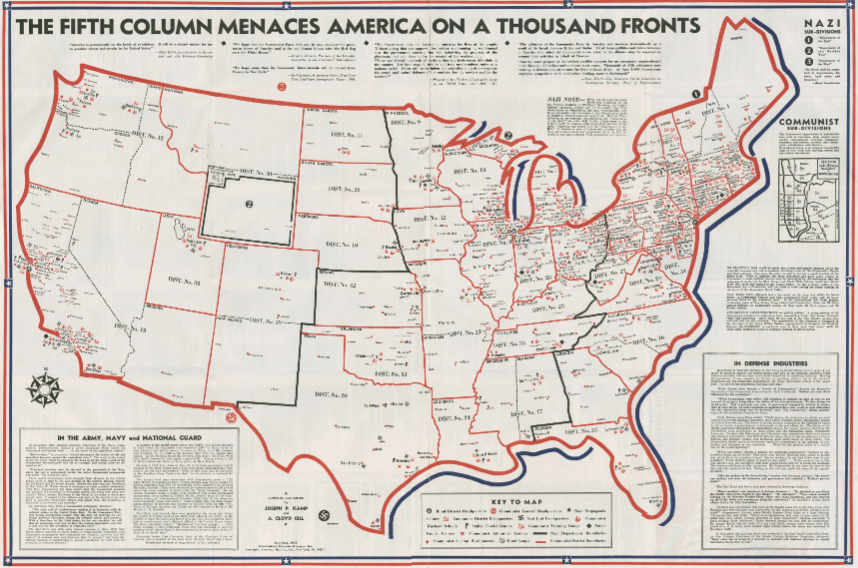

The individuals described in the editorial sought to foment unrest in the name of patriotism and the doctrine of isolationism. While the United States had officially maintained neutrality in World War II, by 1940 it supplied money and munitions to aid Allied resistance efforts. As France struggled desperately to hold off Nazi forces, President Roosevelt delivered an address warning of the dangers of an American “fifth column.”[19] This column was comprised of subversive elements, who tried “to create confusion of counsel, public indecision, political paralysis and, eventually, a state of panic. . . . The unity of the State can be sapped so that its strength is destroyed.” The “fifth column,” Roosevelt asserted, operated like a “Trojan Horse,” which would ultimately betray “a nation unprepared for treachery.” Those inside the bowels of the horse not only opposed war against Hitler, but attempted to undermine efforts to halt his advancements.

The House Committee to Investigate Un-American Activities (HUAC)—better known as the Dies Committee—formed to investigate such subversive groups, including the German-American Bund and Communist Party USA. In 1939, the committee opened an investigation into Pelley, finding that he had been “operating on a nationwide basis,” and that his exploits spanned cities like Detroit, New York, Boston, and even Windsor, Ontario and Villa Acuna, Mexico.[20] Via this network, the committee determined that he disseminated material from the German Ministry of Propaganda, suppressing or misrepresenting its origins to Legion members.[21] The Dies Committee also highlighted his failure to pay his income tax, despite “publishing and distributing for personal profit.” This lucrative material included “booklets and pamphlets containing scurrilous statements, half-truths, re-prints of propaganda of a foreign power, and un-American and unpatriotic material, statements and propaganda.”

By the fall of 1939, Pelley faced a two-front war. The Dies Committee subpoenaed him to appear for a hearing and North Carolina Judge Zeb Nettles signed off on a warrant for his arrest, having violated the terms of probation with his behavior.[22] This behavior, Judge Nettles alleged, consisted of consorting with “‘enemies of American institutions,'” attempting to overthrow the government via his publications, and leveling “‘disgusting epithets at the office of the President of the United States.'”[23] But Judge Nettles and Dies Committee members would be remiss if they expected Pelley to turn himself in. He had apparently been laying low in the State of New York to prepare for another charge of embezzling funds from the Legion.[24] In fact, famed columnist and radio commentator Walter Winchell received information that Pelley, whom he deemed a “Shamerican,” had disguised himself and was hiding in Yorkville, NY. Winchell had heard Pelley was “in need of a physician because he is suffering from fear and shock.”[25]

Perhaps breaking under unrelenting pressure, the ever-elusive Pelley emerged publicly and appeared before the Dies Committee in Washington, D.C. in February 1940.[26] Despite Winchell’s reports, when Pelley at last took the stand before the committee, he was the pinnacle of poise.[27] When pressed about his un-American activities and denouncement of the Dies Committee, he had quite the about-face. Amused columnists noted that Pelley now “thoroughly approves the committee’s work” and offered a “handsome apology” for his past actions. The Palladium-Item reported that Pelley told the group demurely that “‘meeting the committee face to face and finding out what a fine group of Christian gentleman you are'” had changed his mind. He tried to assure the committeemen that, in fact, the Legion was actually a pillar of democracy, as one of its goals was to halt Communism in America. Unfortunately, Pelley conflated Communism with Judaism, and openly admitted his anti-Semitism.[28] However, he assured HUAC that since its committee had proven they took the Communist threat seriously—just by virtue of the committee’s formation—he would gladly dissolve the Silver Shirts.

Pelley’s assurances rang hollow and, as he stepped off the witness stand, Washington police arrested him on behalf of North Carolina officials.[29] He was released on bond after a couple days. In the unfolding months, the Dies Committee renewed its scrutiny, listening to testimony that Pelley had planned to march on Washington with the goal of becoming dictator of the United States.[30] With the walls seemingly closing in, Pelley sought to relocate.

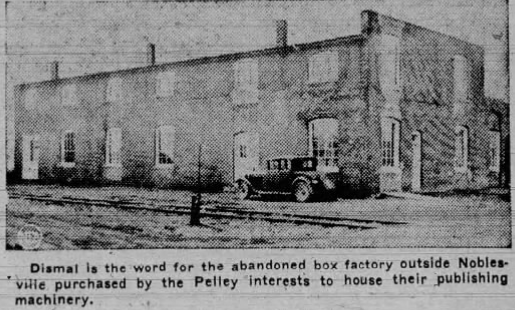

Just days before Christmas 1940, two moving vans departed Biltmore, North Carolina. Throughout the evening, they transported files and printing equipment to a former box factory in Noblesville, Indiana, where former state police officer and Klan member Carl Losey awaited.[31] William Dudley Pelley had appointed Losey president of his new publishing company, Fellowship Press. Newspapers speculated that Losey’s close friend and former Klan Grand Dragon, D. C. Stephenson, would assist in the new endeavor once he was released from his prison sentence for murder. Stephenson vehemently denied any connection to Pelley.[32]

Having experienced the notoriety that came with the Stephenson trial, Noblesville residents wanted nothing to do with the Silver Shirts leader. Regarding Pelley’s move, one editorialist wrote, “We do not want our state to become a center of agitation for intolerant anti-Semitism, American Fascism, and sympathy for Hitler’s Nazism.”[33] Losey tried to assuage their concerns by telling reporters that the forthcoming publication was “‘strictly a magazine for businessmen.'”[34] It would focus solely on political and national events, he assured, saying, “‘I feel that the people are not getting all the truth out of Washington and we propose to get and publish the truth.'”

Pelley himself told the Indianapolis News on Christmas Day that no “‘deep and dark exploits'” were afoot, that his press would only print commercial and “esoteric and metaphysical books.”[35] Seemingly aligned with the caring spirit of the season, he told the paper that he had indeed dissolved the Silver Shirts and would “‘conform my activities to the support of the Dies committee and the government’s efforts to keep this country neutral and at peace.'” Pelley failed to assuage the Dies Committee, however, who sent an investigator to Noblesville, just a couple days after these statements. They sought to investigate the leader of what they dubbed the “New Front,” and learn more about how Pelley financed the operation, the contents of the publications, and the activities of his friend Losey.[36]

An exasperated Pelley told the Indianapolis News that he came to “Indiana for a supposed period of respite from the investigations and persecutions out of Washington and elsewhere covering the last eight years.”[37] He had been living with like-minded benefactors in Indianapolis and commuting to his Noblesville company, despite trying to minimize his role there.[38] The Indianapolis Star reported that Noblesville residents had mixed opinions about Pelley’s presence, with a minority willing to give him a chance to prove the legitimacy of his press. Many others felt like one editorialist, who wrote that the city was “‘heavy at heart,'” and that:

‘If Mr. Pelley and his associates have selected Noblesville as a screen for unfair practices, they will find it extremely difficult to foster such literature upon the community. We sincerely hope they will devote their time and energies to beneficial works that will be a credit to local residents.’

Governor M. Clifford Townsend had no qualms about denouncing Pelley’s activities. While he did not mention Pelley by name, he released a statement on December 28 stating, “‘I feel that it is the opinion of the people of Indiana that there is no place in this state for any organizations or groups which advocate in principle, policies or practice any un-American doctrine.'”[39]

Noblesville Ledger owner D.M. Hudley, too, had no tolerance for Pelley. Before buying the box factory, Pelley, using a fake name, approached Hudley about purchasing the Ledger outright, enticing him with a $10,000 cash down payment.[40] Once Hudley discovered Pelley’s identity and intentions, he turned him away and reported him directly to the Dies investigator temporarily residing in Noblesville. The investigator also had an ally in the Indiana post of the American Legion. Legion representative William E. Sayer stated that the organization was monitoring Pelley, as it “‘is interested in seeing that no Fascist organization or any other group of that type is established in Indiana.'”[41]

Word of Pelley’s presence spread, eliciting a flood of newspaper editorials and even some threats from disapproving Hoosiers. A writer for the Bedford Daily Times stated passionately:

“Hoosiers, notwithstanding, are firm in their belief of freedom of the press. . . . But, if Mr. Losey is supported directly or indirectly by Mr. Pelley, then it is high time that action be taken to rid our state of both! We of Indiana cannot afford to have the good name of our state so besmirched, and it is better that we act early, than late. Borers are not so easily stopped after they have begun their task–they soon work under cover and then, the damage is done.”[42]

Another editorialist wrote to the Richmond Palladium-Item that Indiana, due to its central location, was fast-becoming an “important manufacturing center of military equipment and supplies.”[43] Given this, the writer found it especially “disquieting” that a “notorious American Fascist” had moved his company to the area. One Elwood resident stated in The Call-Leader that “Mr. Pelley’s very presence lends anything but dignity to the situation” and that “As far as Hoosiers generally are concerned, this ‘fountain of Fascism’ can bubble elsewhere.”[44]

Losey claimed that the deluge of resistance included a letter “‘threatening to blow the place up and attempting to kidnap his night watchmen.'”[45] Days later he requested that Noblesville police officers investigate individuals who threw a rock through the plant windows in the early morning hours before fleeing in an automobile.[46] Losey increased secrecy around the plant’s efforts and tried to temper concerns by telling the Indianapolis Star that Fellowship Press’s magazine would focus on isolationism. He noted that “‘The object of our publication is to keep America Christian and to keep American boys out of a foreign war.'”[47]

The first issue of Pelley’s new publication, the Weekly Roll Call, confirmed Hoosiers’ skepticism. It included conspiratorial, anti-Semitic cartoons. One depicted Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins ignoring the economic plight of Americans, while providing idyllic homelands for Jewish refugees.[48] Hoosier retailers demonstrated their opposition to such material by refusing to distribute the Roll Call. The Indianapolis Star reported that “Sale of the first issue, placed on the stands late last week, was slight, with ‘plenty of leftover copies.'”[49] Floundering, Losey was let go, and Pelley took full control of Fellowship Press.[50]

He leveraged his press weeks later, seemingly to resurrect the Silver Shirts. In April 1941, North Carolina authorities appealed to Indiana for help in extraditing Pelley, on the grounds of violating the terms of his probation. Pelley printed and circulated 10,000 copies of a letter requesting support from Silver Shirt Legion members, who resided in twenty-two states.[51] Alas, his devoted readership failed to mobilize and ultimately he returned to North Carolina to answer to the charges.

With Pelley’s case pending, an event occurred that would change the course of history. On December 7, 1941, Japan bombarded an American naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The surprise attack prompted President Roosevelt to issue his “Day of Infamy” speech and Congress to declare war on Japan. In an editorial, Pelley wrote solemnly, “It is time for patriotic wisdom, calmness and courage. We must devote ourselves towards winning the war. Let no one capitalize on the war.”[52] He announced the suspension of Roll Call, stating that for the foreseeable future, Fellowship Press would only print biographies and spiritual material. Of the Silver Shirts, he would ensure that they were at the military’s beck and call. The Noblesville Ledger suggested his pandering stemmed from fear that the patriotic fervor would negatively influence his upcoming hearing in North Carolina.

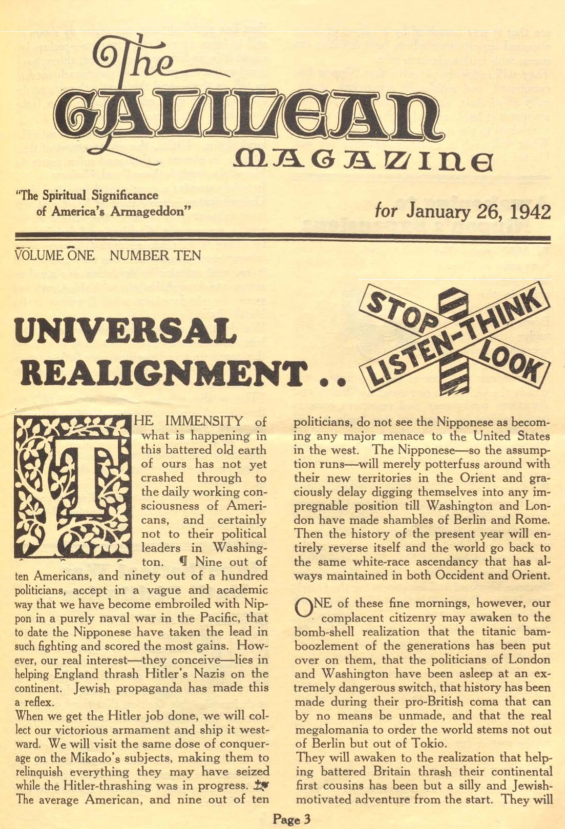

Although Pelley suspended the Roll Call, his press continued publication of The Galilean, marketed as a spiritual magazine. [53] With the U.S. fully entrenched in war, the U.S. Post Office barred its distribution and U.S. Attorney General Francis Biddle ordered Pelley’s arrest on the grounds that it violated the Espionage Act of 1917.[54] He was charged with attempting “to cause insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny and refusal of duty in the military and naval forces of the United States of America.'” On an April morning in 1942, FBI agents pounded on the door of George B. Fisher, who had previously donated $20,000 to the Silver Shirts. They were correct in their belief that Pelley was laying low at his Darien, Connecticut residence. The Silver Shirt leader arose from bed, was handcuffed, and transported to the Marion County Jail. That same day, his 21-year-old son entered the Army.[55]

As Pelley sat in jail, awaiting friends to transfer bail money—one offered to sell his $27,000 Meridian Street property—he chain smoked and expounded on his philosophies to the police marshal. With characteristic bluster and showmanship, he gladly “posed for photographs, amiably answered most questions and skillfully parried others.”[56] Bail money arrived a few days later and the Indianapolis News reported that he “was neatly dressed and puffing on a pipe when he was brought from his cell.”[57] Pelley reunited with his daughter, Adelaide, at the federal building in Indianapolis, where his sedition trial would take place.[58]

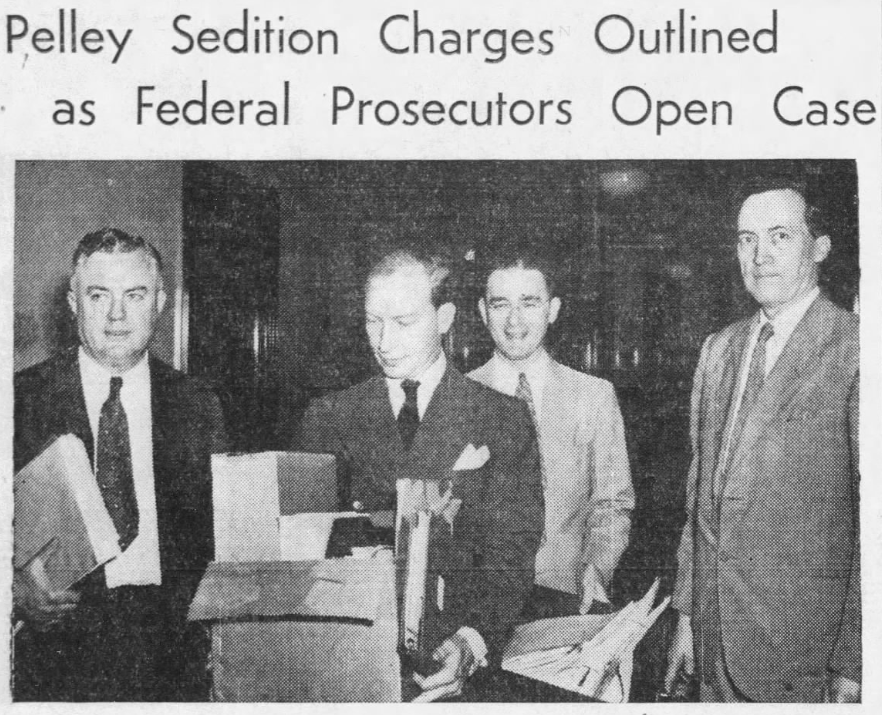

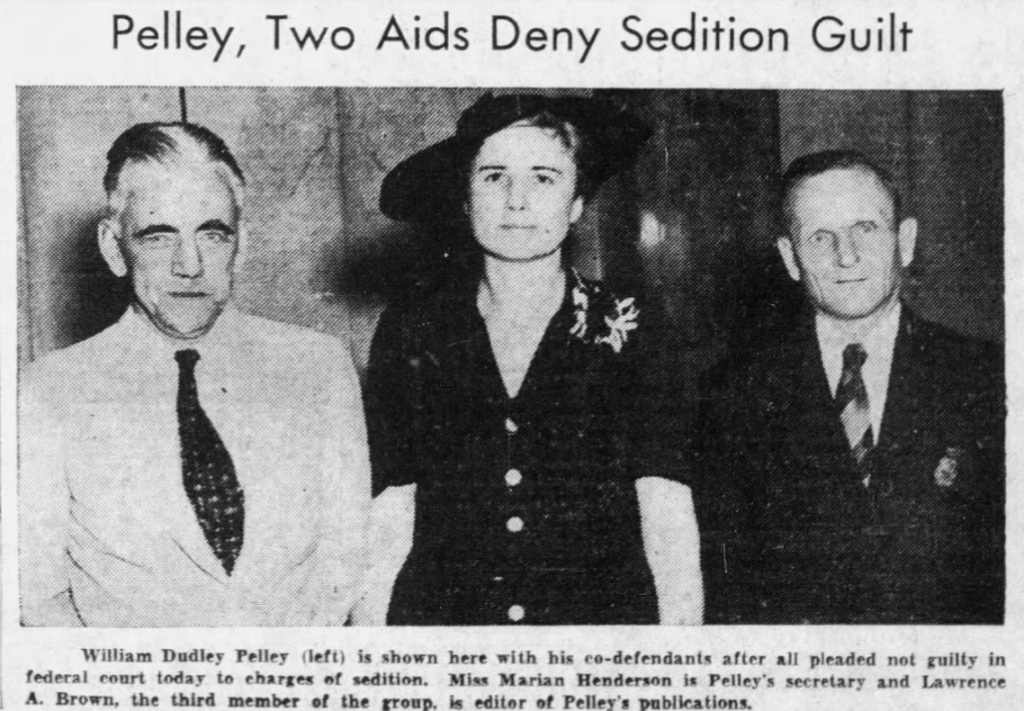

In late July 1942, Pelley and two Fellowship Press associates arrived at the federal court in Indianapolis for the “first major sedition prosecution in America since Pearl Harbor.”[59] They faced several counts, including attempts “to interfere with the operation and success of military and naval forces of the United States and to promote the success of its enemies.”[60] At the time of their trial, these enemies were undertaking the systematic deportation of Jews from Warsaw to the Treblinka extermination camp in Poland. “Final Solution” architect Heinrich Himmler had recently instructed doctors to conduct medical experiments on prisoners at Auschwitz concentration camps.

As millions experienced unspeakable suffering abroad, Hoosiers were summoned to determine the fate of William Dudley Pelley and his c0-conspirators. The all-male jury hailed from cities around Indiana and belonged to a variety of professions, including engineering, farming, and insurance sales.[61] The trial captivated the nation, as many wondered if the untouchable Pelley would finally experience harsh consequences.

Check back for Part II to learn Pelley’s fate, would ultimately be decided in an Indianapolis courtroom. We’ll also delve into “Soulcraft,” the theology Pelley developed later in life. Based out of Noblesville, Soulcraft Press published works about his new spiritual belief, which incorporated the occult and the extraterrestrial—not unlike the emergent religion of one L. Ron Hubbard.

Notes:

[1] “Pelley Forces Trial Here After His Seizure as Enemy of U. S.,” Indianapolis News, April 4, 1942, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; “America’s No. 1 seditionist” quote from “Pelley’s Case May Not Take So Much Time,” Noblesville Ledger, July 30, 1942, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[2] “‘Little Fuehrer’ Moves In,” The Republic (Columbus, IN), December 27, 1940, 4, accessed Newspapers.com.

[3] Jason Daley, “The Screenwriting Mystic Who Wanted to Be the American Fuhrer,” Smithsonian Magazine, October 3, 2018, accessed smithsonianmag.com.

[4] “William Dudley Pelley,” U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, June 5, 1917, accessed Ancestry Library; William Dudley Pelley, “Idols Mended,” The Red Book Magazine (November 1922): 83-87, accessed Archive.org; William Dudley Pelley, “There Are Still Fairies,” The Sunday Star (Washington, D.C.), July 8, 1923, 2, accessed Archive.org; George C. Shull, “Pelley, Man Who Died for Seven Minutes, Says Pyramid Predicts Career End in ’45,” Indianapolis Star, December 28, 1940, 2, accessed Newspapers.com.

[5] William Dudley Pelley, “Seven Minutes in Eternity—the Amazing Experience that Made Me Over,” The American Magazine (March 1929): 7, accessed Archive.org.

[6] Daley, “The Screenwriting Mystic Who Wanted to Be the American Fuhrer.”

[7] Jon Elliston, “Asheville’s Fascist: William Dudley Pelley’s Obscure But Infamous Silver Shirt Movement Lives on in His Paper Trail,” WNC Magazine (January/February 2018), accessed wncmagazine.com.

[8] Elliston, “Asheville’s Fascist.”

[9] “Charge Breaking of Blue Sky Law,” News and Observer (Raleigh, NC), August 22, 1934, 12, accessed Newspapers.com.

[10] Silver Shirt Enrollment Application, 1930s, William Dudley Pelley and the Silver Legion of America Collection, S1050, Rare Books & Manuscripts Division, Indiana State Library.

[11] “Pelley, Summerville Convicted by Court,” News and Record (Greensboro, NC), January 23, 1935, 4, accessed Newspapers.com; “W. D. Pelley is Declared Guilty,” News and Observer (Raleigh, NC), January 23, 1935, 2, accessed Newspapers.com; “Silver Shirt Duo Sentenced Today,” Salisbury Post (North Carolina), February 18, 1935, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[12] “Pelley for President: Silver Shirt Man to Run,” The Sentinel (Winston-Salem, NC), September 10, 1935, 11, accessed Newspapers.com; “Pelley Sees ‘Theocratic State’ in U.S.,” Asheville Times (North Carolina), January 25, 1936, 10, accessed Newspapers.com; Elliston, “Asheville’s Fascist.”

[13] “Anti-Semitic Silver Shirt Handbook Flays New Deal, Urges Axis, U.S. Unity,” Indianapolis Star, December 29, 1940, 4, accessed Newspapers.com.

[14] George C. Shull, “Pelley, Man Who Died for Seven Minutes, Says Pyramid Predicts Career End in ’45,” Indianapolis Star, December 28, 1940, 2, accessed Newspapers.com; Quote from “Jury Hears of Pelley ‘Oracle,'” Indianapolis News, July 29, 1942, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[15] Daley, “The Screenwriting Mystic Who Wanted to Be the American Fuhrer.”

[16] “Guard Captain Testifies Before Dies Committee,” Star Press (Muncie, IN), April 5, 1940, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; “Hoosier Tells of Silver Shirt Plot,” Indianapolis News, April 5, 1940, 5, accessed Newspapers.com.

[17] “Guard Captain Testifies Before Dies Committee,” Star Press (Muncie, IN), April 5, 1940, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[18] “UnAmerican Troublemakers,” Bremen Enquirer (Indiana), March 7, 1940, 6, accessed Newspapers.com.

[19] “Roosevelt’s Address on the ‘Fifth Column,'” May 26, 1940, U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of the National Archives & Records Administration.

[20] “Head of Silver Shirts Misused Assets of Publishing Firm, Dies Probers Told,” Reading News (Pennsylvania), August 29, 1939, 16, accessed Newspapers.com.

[21] “Pelley is Accused of Disseminating Nazi Propaganda,” Nashville Banner (Tennessee), October 3, 1939, 14, accessed Newspapers.com.

[22] “Committee Tries to Subpoena Head of Silver Shirts,” Evening Courier (Camden, NJ), August 24, 1939, 2, accessed Newspapers.com; “Pelly [sic] is Cited to State Court,” Rocky Mount Telegram (North Carolina), October 19, 1939, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[23] “Pelly [sic] is Cited to State Court,” Rocky Mount Telegram (North Carolina), October 19, 1939, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[24] “Pelly [sic] is Cited to State Court,” Rocky Mount Telegram (North Carolina), October 19, 1939, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; “Tax Collector Receives Check for Pelley Taxes,” Asheville Citizen Times, November 4, 1939, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; “Behind the Scenes in Washington,” Lancaster Eagle-Gazette (Ohio), December 8, 1939, 6, accessed Newspapers.com.

[25] “Winchell Says W.D. Pelley is in N. Y. Town,” Asheville Citizen-Times, February 5, 1940, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; Walter Winchell, “Broadway,” Evansville Courier, February 14, 1940, 6, accessed Newspapers.com.

[26] “Pelley Surrenders to Dies Body; Ask He Be Held for Court Here,” Asheville Times, February 6, 1940, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[27] Richard L. Turner, “Pelley Angers Dies Probers; Tells Income,” Palladium-Item (Richmond, IN), February 8, 1940, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[28] “Silver Shirts Get $240,000 from Friends,” The Times (Munster, IN), February 9, 1940, 11, accessed Newspapers.com.

[29] “Pelley Nabbed for Violation of Probation,” Palladium-Item (Richmond, IN), February 11, 1940, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; “Silver Shirt Leader Gains Jail Release,” Journal and Courier (Lafayette, IN), February 12, 1940, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[30] “Silver Shirt Linked with Army Group,” Vidette-Messenger of Porter County (Valparaiso, IN), April 2, 1940, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[31] “Furniture En Route,” Indianapolis News, December 20, 1940, 25, accessed Newspapers.com; “Rumors that Stephenson to Get Pardon,” Noblesville Ledger, December 20, 1940, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[32] “Rumors that Stephenson to Get Pardon,” Noblesville Ledger, December 20, 1940, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[33] “Indiana Doesn’t Want Him,” Palladium-Item (Richmond, IN), January 5, 1941, 16, accessed Newspapers.com.

[34] “Silver Shirts Leader Mentioned in Noblesville Magazine Mystery,” Indianapolis Star, December 20, 1940, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[35] “Pelley Denis Any ‘Mystery,'” Indianapolis News, December 25, 1940, 18, accessed Newspapers.com.

[36] “Noblesville Firm to Publish Books,” Palladium-Item (Richmond, IN), December 27, 1940, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; “Dies Committee Watches Pelley,” Indianapolis Star, December 28, 1940, 2, accessed Newspapers.com; “Committee Sends Man to Open Inquiry,” Noblesville Ledger, December 31, 1940, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[37] “Pelley Denies Contact with Stephenson,” Indianapolis News, December 27, 1940, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[38] Donovan A. Turk, “Losey, Pelley Await Dies Quiz; Hold ‘Christian Crusade’ is Object,” Indianapolis Star, December 28, 1940, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[39] Edward L. Throm, “Says Indiana Has No Place for Disloyal,” Indianapolis Star, December 28, 1940, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[40] Daniel M. Kidney, “Dies Aide Says Pelley Tried to Buy Hoosier Newspaper,” Evansville Press, December 31, 1940, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[41] “Legion Watches Publishing Firm,” Indianapolis Star, December 30, 1940, 12, accessed Newspapers.com.

[42] “Some Americans . . .,” Bedford Daily Times, January 2, 1941, 6, accessed Newspapers.com.

[43] “Indiana Doesn’t Want Him,” Palladium-Item (Richmond, IN), January 5, 1941, 16, accessed Newspapers.com.

[44] “Fountains of Fascism,” Call-Leader (Elwood, IN), January 9, 1941, 4, accessed Newspapers.com.

[45] Daniel M. Kidney, “Dies Aide Says Pelley Tried to Buy Hoosier Newspaper,” Evansville Press, December 31, 1940, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[46] “Losey Magazine Press Time in Air,” Indianapolis Star, January 11, 1941, 9, accessed Newspapers.com.

[47] Ibid.

[48] “Anti-Semitic Cartoons in New Magazine Found Similar to Silver Shirt Program,” Indianapolis Star, January 14, 1941, 13, accessed Newspapers.com.

[49] “Pelley Offers New Publication,” Indianapolis Star, January 21, 1941, 3, accessed Newspapers.com.

[50] “Pelley Succeeds Losey as New Magazine Agent,” Indianapolis News, March 11, 1941, 11, accessed Newspapers.com.

[51] “Pelley Asks Silver Shirt Aid in Fight Against Extradition,” Palladium-Item (Richmond, IN), April 17, 1941, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[52] “Suspension of the Roll-Call is Announced,” Noblesville Ledger, December 15, 1941, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[53] “Pelley Faces Trial Here after His Seizure as Enemy of U. S.,” Indianapolis News, April 4, 1942, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[54] Ibid.

[55] “Pelley Now in Jail for Lack $15,000 Bond,” Noblesville Ledger, April 6, 1942, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[56] Ibid.

[57] “Pelley Released on $15,000 Bond,” Indianapolis News, April 11, 1942, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[58] “Pelley Faces Trial Here After His Seizure as Enemy of U. S.,” Indianapolis News, April 4, 1942, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[59] “Pelley Sedition Trial is Begun,” Indianapolis News, July 28, 1942, 3, accessed Newspapers.com.

[60] “U. S. Marshal Visits Office of W. D. Pelley,” Noblesville Ledger, June 10, 1942, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[61] “Pelley Sedition Trial is Begun,” Indianapolis News, July 28, 1942, 3, accessed Newspapers.com.