Shells rained down on men who had endured disease, the obliteration of their comrades, sleep deprivation, the constant shriek of ammunition, and the literal smell of death. Burrowed into dirt along the Western Front, these Allied men slugged it out in a battle of wills and weaponry until they defeated the Central Powers in 1918. Many of the American troops that helped ensure victory in World War I, as well as the surgeons waiting on hand in ambulances to treat shrapnel-torn faces, were there, in part, because of the efforts of Indiana dentist Otto King. For Dr. King, dentistry went beyond staving off cavities and engineering attractive smiles. He applied his dental skills to a greater good both abroad and at home, and encouraged the nation’s dentists to follow suit. This meant mobilizing dentists to treat war-induced maxillofacial trauma and establishing free dental clinics for poor children who missed school due to untreated oral issues.

After graduating from the Northwestern University Dental School in 1897, Dr. King practiced dentistry in his hometown of Huntington, Indiana. He assumed a national leadership role in his profession in 1913, when he was elected the general secretary of what is today known as the American Dental Association (ADA). The role of general secretary was equivalent to that of a modern executive director. Dr. King helped transform dentistry from a trade to a profession through the establishment of The Journal of the American Dental Association (JADA), published in Huntington and distributed nationally. Dentists across the country—notably those in remote areas—could learn about best practices, research findings, educational and professional opportunities, and new dental theories through articles like “The Functions of Dentistry and Medicine in Race Betterment” (1914) and “Commercialism vs. Professional Ethics” (1915).

Editor King also used the journal to mobilize dentists for World War I service and published findings related to war-related injuries, such as Leo Eloesser’s 1917 “Gunshot Wounds and Lesions Produced by Shell and Shrapnel in the Jaws and Face.” Just days before the U.S. entered World War I by declaring war on Germany in 1917, Dr. King gave an interview printed in newspapers across the country about the Preparedness League of American Dentists, an extension of the ADA. The emergence of trench warfare during the “gravest crisis” in history created an urgent need for dentists on the frontlines and the Preparedness League worked to recruit dentists for Army and Navy service from every state, as well as Puerto Rico, the Philippine Islands, and Canada. Dr. King did his part when Colonel Kean ordered him to choose dentists to serve at base hospital No. 32, located in Indianapolis, in July 1917.

Dr. King explained that the league would respond to this need by securing “in each locality, a nucleus of the trained dental specialists, who will assist in the instructions of the members of the unit along the lines of war dental surgery, as a measure of preparedness against war and to co-operate in treatment of wounds of the jaws and face, in case of actual warfare.” He stated that “Whereas Red Cross base hospitals are being formed, we are, as fast as possible, organizing dental units in connection therewith and co-operation is established between the organizations.”

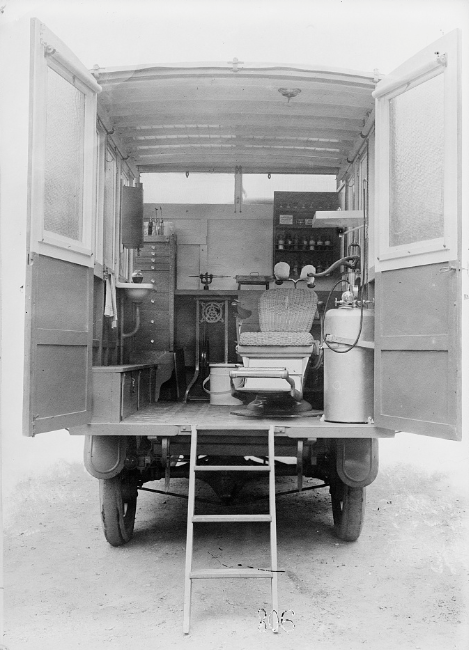

The New York Times reported that the Preparedness League outfitted dental ambulances sent to the warfront to reach patients in “out-of-the way places.” In addition to treating the wounded, these ambulances isolated men in order to prevent the spread of diseases like mumps and German measles. The Times reported that “at least 20 per cent of the men are incapacitated and kept from active service on account of illness finding its source in diseased conditions of the mouth.” These state-of-the-art ambulances included a fountain cuspidor, electric lathe, sanitation cabinet, steam sterilizer, nitrous oxide, vulcanizer, and a typewriter on which to record treatment findings. A secondary use for these ambulances involved relief work in France, where the Red Cross mobilized dentists to treat the teeth of children.

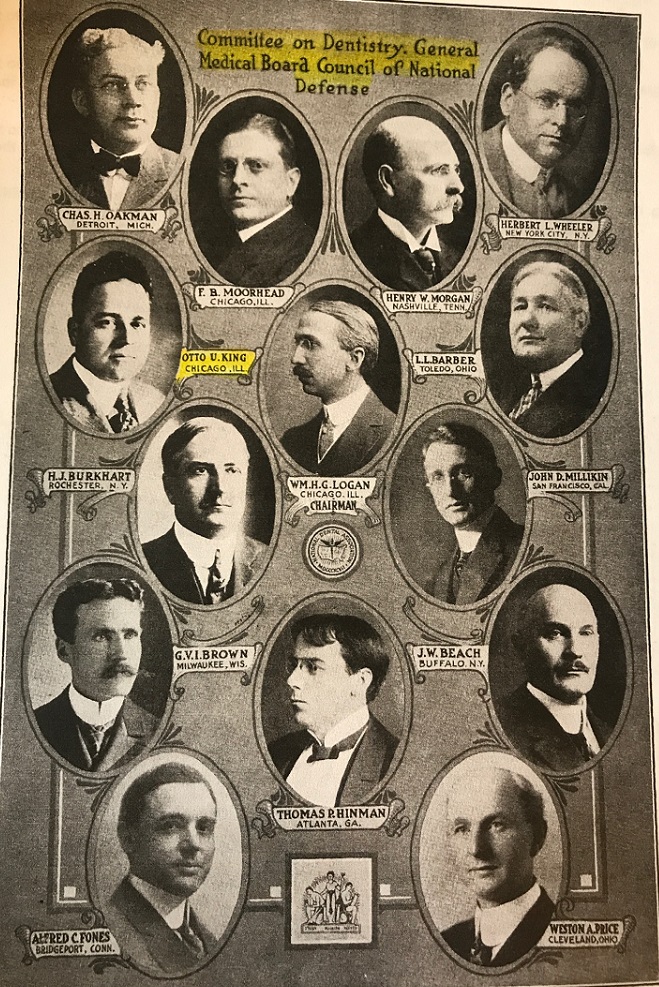

Because of his work with the Preparedness League, Dr. King was appointed as one of twelve members on the Committee on Dentistry, General Medical Board of the Council of National Defense. He headed the Committee on Publicity, a subcommittee tasked with recruiting dentists for Army service. Dr. King utilized JADA for this purpose, including a blank application to the Dental Reserve Corps and publishing pieces like “You Can Help Win the War!—An Appeal for Prompt Individual Service by Every Member” and “How May You Assist the Medical Department of the United States Army?”

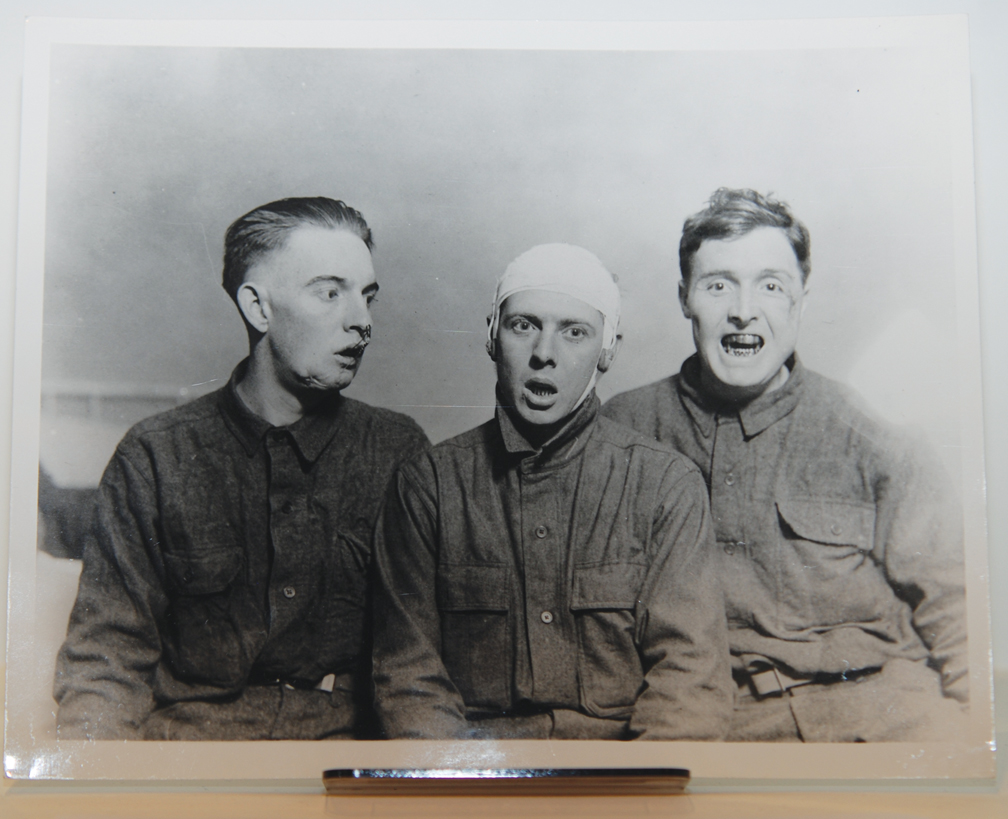

In one article, U.S. Army dentist Dr. John S. Marshall detailed the morbid gamut of dental injuries awaiting military personnel, including:

blows upon the face from the closed fist; kicks of horse or mule; the impact of some heavy missile propelled with considerable force; the extraction of teeth, tho this is rare; a fall from a horse, bicycle, or a gun-carriage; the passage of a wheel over the face; and gunshot injury in line of duty or from accident, or design, with suicidal intent or otherwise.

He lamented the devastation wrought by shell fragments, which “tear away the soft tissues and underlying bone, leaving a hideous and ghastly wound.” Because of these traumas, “the Oral Surgeon has during this World War come into his own.” These surgeons not only performed life-saving procedures, but also helped restore facial features in what the Chicago Tribune described in 1918 as “a new branch of the healing art—that of plastic surgery.” The Decatur, Illinois Daily Review noted that working to reverse oral disfigurement “have given the dentists a new distinction.”

In addition to injuries, success on the battlefield was impeded by defective teeth, as they hindered the ability to eat and subsequently weakened the fighting force. Dr. King thus noted the importance of the U.S. Army Dental Corps, stating “It is truly said that an army fights on its stomach and teeth . . . As monitors of the teeth, the dentists are supervisors of the stomach, hence, the army is helpless without our professional officers.”

But just getting troops onto the battlefield proved to be a challenge. Dr. King utilized his prominence in the profession to convince dentists to treat recruits barred from service due to dental issues—at no cost. He warned that “more than 2,000 applicants for enlistment were in danger of being refused entrance into the fighting force of the nation because of defective teeth.” In April 1917, he volunteered to personally treat rejected recruits and he convinced local dentists to prepare the mouths of two rejected recruits. Under his direction, the ADA hosted a “Help Win the War” convention in 1918, which featured a series of clinics about dental treatment and military recruitment.

The Chicago Tribune reported that by the time of the conference, Preparedness League members had performed more than 500,000 free operations on recruits, enabling the men to pass the military’s physical examination. A letter printed in the JADA encouraged dental colleges, dispensaries, and hospital clinics to work with the Preparedness League to treat the mouths of recruits. The author lamented that the criteria for military acceptance included only “a mouth free from disease producing conditions and four (4) opposing molars, two on either side . . . This requirement is a joke but we can change it no doubt, if desired.”

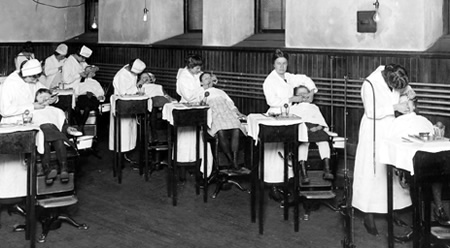

With the conclusion of the Great War, Dr. King intensified his efforts to bring his “great humanitarian mission” to fruition. This involved educating the public about importance of dental prevention, particularly among children. He noted that most infectious diseases, such as diphtheria and small-pox, entered through the nose and mouth, making the maintenance of a healthy oral environment crucial. He observed that many children missed school due to infections and malnutrition caused by defective teeth, but their parents lacked the resources to treat the maladies. Dr. King hoped to prevent these painful and disruptive dental issues by educating children about hygiene, through demonstrations and nursery rhymes, and by offering free preventative treatment. In an address about oral hygiene, Dr. King proclaimed that “For years we have been trying to dam back or cure diseased bodies, due to neglected Oral Hygiene conditions, but overlooking the source or beginning of life as represented in childhood as the place to teach and establish preventative medicine.”

Dr. King helped establish free clinics on the East Coast and implored the public and lawmakers to invest in their establishment, stating in 1917 that “Disease is a social menace, an enemy of the State.” In a 1920 criticism of American dental care, he noted that “The children of our country deserve as effective physical care as the livestock.” He anticipated backlash for proposing free dental clinics, but argued that “socialized health” should be wielded as a weapon against “capitalized disease.” Dr. King’s dogged belief that dentistry could uplift humanity radiated from the trenches of Gallipoli to classrooms in New York.

Learn more about the extraordinary Dr. Otto King with IHB’s new historical marker.