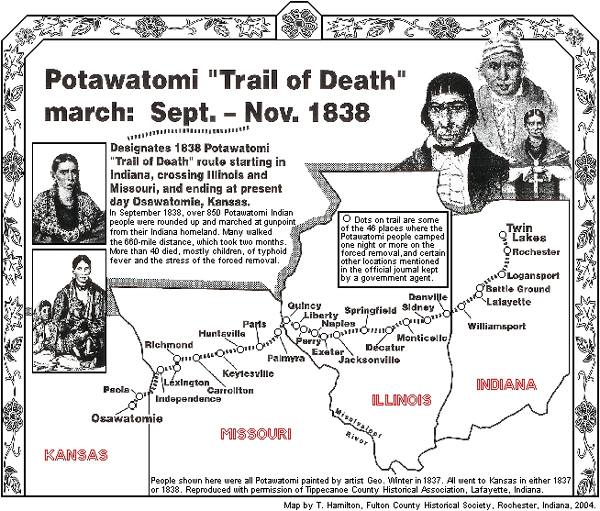

This is Part One of a two-part post. Part One examines why IHB and local partners chose to refocus the text of a new historical marker to Sycamore Row in Carroll County that replaces a damaged 1963 marker. Instead of focusing on the unverifiable legends surrounding the row of sycamores lining the Old Michigan Road, this new marker centers the persecution and removal of the Potawatomi to make way for that road and further white settlement. Part Two will look in depth at the persecution of the this indigenous group by the U.S. government as well as the resistance and continued “survivance” of the Potawatomi people.*

What’s in a Legend?

The sycamore trees lining the Old Michigan Road have long been the subject of much curiosity and folklore in Carroll County. But there is a story here of even greater historical significance – the removal and resistance of the Potawatomi. While the trees will likely continue to be the subject that brings people to this marker, IHB hopes to recenter the Potawatomi in the story. (To skip right to the story of the Potawatomi, go to Part Two of this post, available April 2021).

Folklore is a tricky area for historians. The sources for these stories are often lost, making it difficult to determine the historical accuracy of the tale. But historians shouldn’t ignore folklore either. Local stories of unknown origin can point to greater truths about a community. It becomes less important to know exactly if something really happened and more significant to know why the community remembers that it did.

Folklore is both a mirror and a tool. It can reflect the values of the community and serve to effect change. Folklore surrounding “Sycamore Row” in Carroll County does both of these things. Continuing local investment in this row of trees reflects a community that values its early history. At the same time, these trees have served as a preservation tool bringing this community together time and time again for the sake of saving a small piece of Indiana’s story.

These are the big ideas around folklore, but what about searching for the facts behind the stories? In the case of Sycamore Row, digging into the events that we can document only makes the story more interesting and inclusive. And it gives us the opportunity to reexamine the central role of the Potawatomi in this history and return it to the landscape in a small way.

Sycamore Row

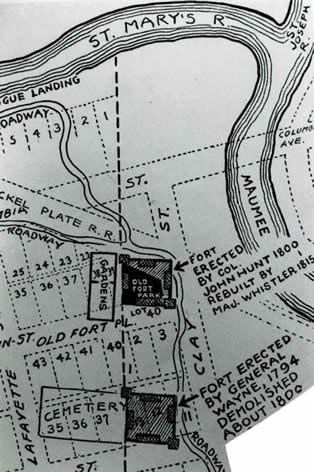

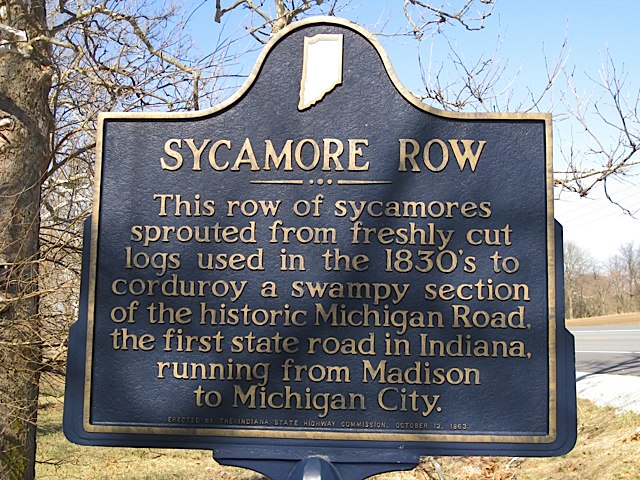

In 1963, the Indiana Historical Bureau placed a marker for “Sycamore Row” on State Road 29, formerly the Old Michigan Road. The 1963 marker read:

This row of sycamores sprouted from freshly cut logs used in the 1830’s to corduroy a swampy section of the historic Michigan Road, the first state road in Indiana, running from Madison to Michigan City.

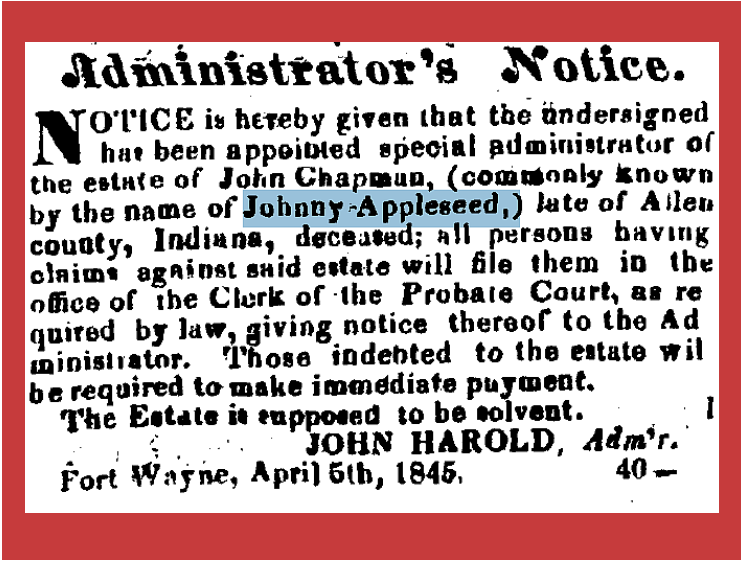

IHB historians of the 1960s presented this theory on the origin of the sycamores as fact. Today, IHB requires primary documentation for all marker statements. While there are secondary sources (sources created after the event in question), there are no reliable primary sources for this statement. In fact, we don’t know where the trees came from. Local legend purports that saplings sprang from the logs used to lay the “corduroy” base when the dirt road was planked in the 1850s. There is evidence that sycamores were used on this section of the road. During road construction in the 1930s, the Logansport Press reported that workers discovered sycamore logs under the road near the famous Fouts farm. And it is possible that some saplings could have grown on their own, though it’s unlikely they sprouted from the logs. Local historian Bonnie Maxwell asked several experts for their take. One Indiana forester wrote that it was more likely that the trees sprouted from seeds that took root in the freshly dug furrows next to the road. Others noted that even if the trees sprouted as the legend claims, they would not be the same trees we see today, as they are not large enough have sprouted in the early 19th century. Other theories have been posited as well, including one from a 1921 Logansport-Pharos article claiming that the trees were planted to protect the creek bank during road construction in the 1870s. Regardless, we know from Carroll County residents that there have been sycamores along that stretch of road for as long as anyone can remember. It matters less to know where the trees came from and more to know why they have been preserved in memory and in the landscape. [1]

Preservation and Community Building

The ongoing preservation and stewardship of Sycamore Row tells us that local residents care about the history of their community. The trees provide a tangible way of caring for that history. To that end, Carroll County residents have joined together many times over the years to protect the sycamores.

In the 1920s, the Michigan Road section at Sycamore Row became State Road 29 and some of the trees were removed during paving. Starting in the 1930s, road improvements planned by the state highway department threatened the sycamores again, but this time local residents acted quickly. In November 1939, the Logansport Pharos-Tribune reported that Second District American Legion commander Louis Kern organized opposition to a state highway department plan to remove 19 sycamores in order to widen the road. Local residents joined the protest and the state highway commission agreed to spare all but five of the 127 sycamore trees during the highway expansion. [2]

By the 1940s, newspapers reported on the dangerous and narrow stretch of road between the sycamores where several accidents had occurred. By the 1960s, local school officials worried about school busses safely passing other cars and trucks on the stretch and proposed cutting down the trees to widen the road. In 1963, Governor Matthew Walsh issued an order to halt the planned removal of sixty-six of the sycamores and the state highway department planted twenty new trees. Many still called for a safer, wider road and the local controversy continued. [3]

In 1969, officials from the school board and the Carroll County Historical Society (CCHS) met to discuss options for improving driving conditions, weighing this need against the historical significance of the sycamores. Meanwhile, the state highway department continued planning to widen the road, a plan that would have required cutting down the trees. The CCHS staunchly opposed removing the sycamores and organized support for its efforts. The organization worked for over a decade to save Sycamore Row, petitioning lawmakers and gaining the support of Governor Edgar Whitcomb. Carroll County residents signed petitions and spoke out at public meetings with the state highways commission. Ultimately, in 1983, the state highway department announced its plan to reroute SR 29 around the sycamores. This grass roots effort, focused on preserving local history, had prevailed even over the needs of modernization. Construction on the new route began in 1987. The Logansport Pharos-Tribune reported that residents then began using the section of the Old Michigan Road to go down to the bank of the creek and fish. [4]

In 2012 the Friends of Carroll County Parks took over stewardship of Sycamore Row and began planting new sycamore saplings the following year. In 2020 they planted even larger sycamores to preserve the legacy for future generations. They also took over the care of the 1963 historical marker, repainting it for the bicentennial. In late 2020, the marker was damaged beyond repair and had to be removed. This opened up an opportunity for IHB, the Friends, and the CCHS to place a new two-sided historical marker. The marker process is driven by applicants, either individuals or community organizations, and then IHB works with those partners, providing primary research to help tell their stories. We work together, sharing authority. These Carroll County organizations still want to tell the story of the sycamores, but recognize that there is complex history beyond the legends.

Re-centering the Potawatomi

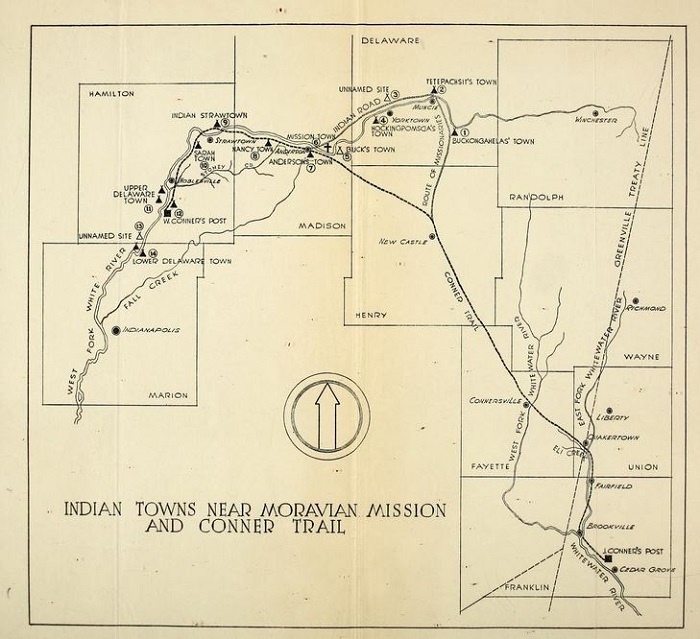

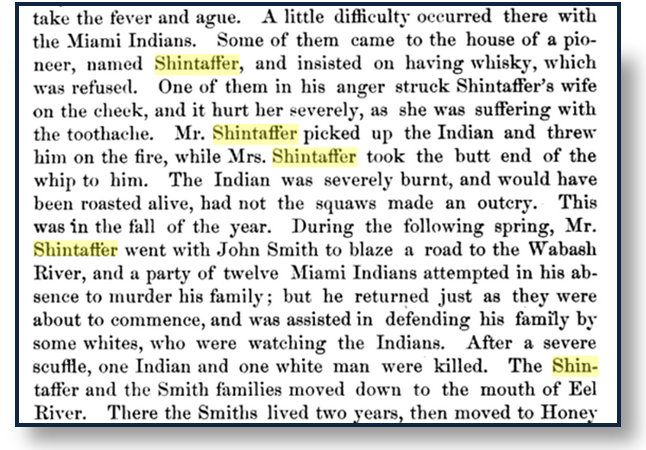

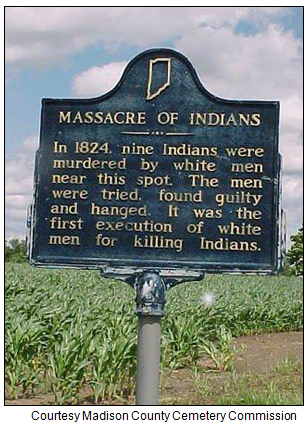

IHB and local partners are using the extra space on the double-sided marker to include the Potawatomi in the story of Sycamore Row. While there is no way we can give the history of these indigenous peoples in all its complexity in the short space provided on a marker, we can make sure it is more central. After all, the story of the genocide, removal, and resistance of the Potawatomi to settler colonialism is part of the story of Indiana.

Some people have a negative view of this kind of reevaluation of sources and apply the label “revisionist” to historians updating the interpretation of an old story. However, “historians view the constant search for new perspectives as the lifeblood of historical understanding,” according to author, historian, and Columbia professor Eric Foner. [5] As we find new sources and include more diverse views, our interpretation changes. It becomes more complex, but also more accurate. And while there is a temptation to view history as a set of facts, or just as “what happened,” it is always interpretive. For instance, the act of deciding what story does or does not make it onto a historical marker is an act of interpretation. When IHB omits the Native American perspective from a historical marker we present a version of history that begins with white settlement. It might be simpler but its not accurate. There were already people on this land, people with a deep and impactful history. When historians and communities include indigenous stories, they present a version of Indiana history that is more complex and has a darker side. This inclusion reminds us that Indiana was settled not only through the efforts and perseverance of the Black and white settlers who cleared the forests, established farms, and cut roads through the landscape. It was also settled through the removal and genocide of native peoples. Both things are true. Both are Indiana history.

With this in mind, the new two-sided marker at Sycamore Row will read:

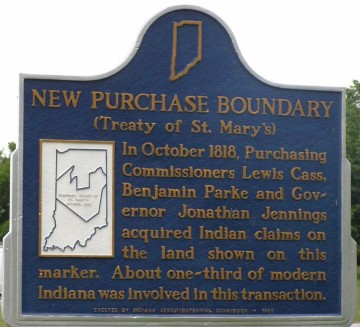

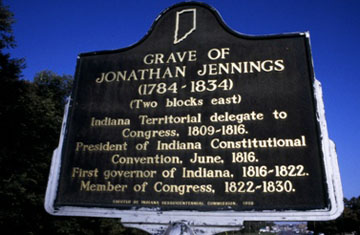

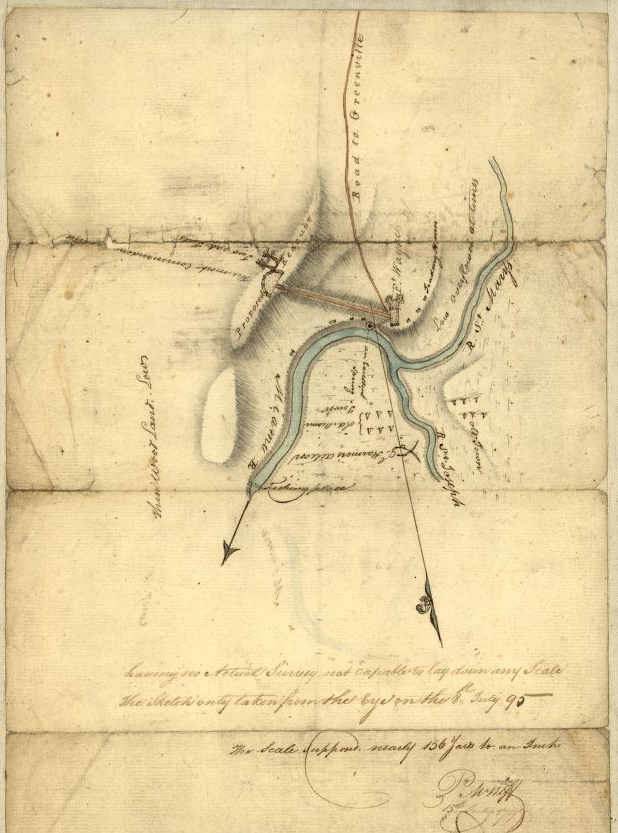

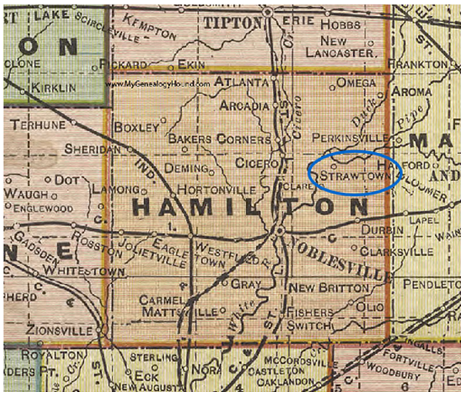

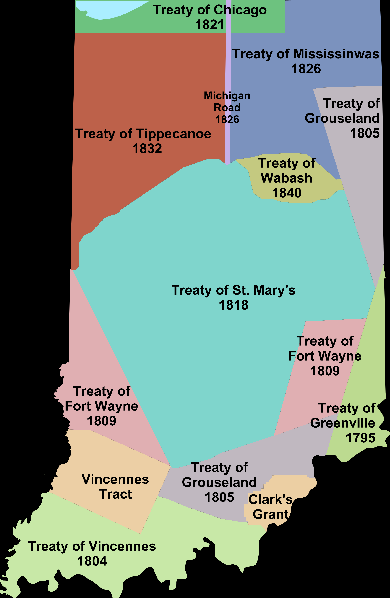

The sycamores here line the sides of the Michigan Road, which connected the Ohio River with Lake Michigan and further opened Indiana for white settlement and trade. Under intense military and economic pressure, Potawatomi leaders ceded the land for the road in 1826. John Tipton, one of the U.S. agents who negotiated this treaty, purchased the land here in 1831.

The state began work on the road in the 1830s. While there are several theories on how the trees came to be here, their origin is uncertain. By the 1930s, road improvements threatened the trees, but residents organized to preserve them over the following decades. In 1983, the Carroll County Historical Society petitioned to reroute the highway and saved Sycamore Row.

Of course, this does little more than hint at the complex history of the Potawatomi. Markers can only serve as the starting point for any story, and so, IHB uses our website, blog, and podcast to explore further. In Part Two of this post, we will take an in-depth look at the persecution of the Potawatomi to make way for the Michigan Road, their resistance to unjust treaty-making, their removal and genocide as perpetuated by the U.S. government, and the continued “survivance” of the Potawatomi people today in the face of all of this injustice.

*”Survivance” is a term coined by White Earth Ojibwe scholar Gerald Vizenor to explain that indigenous people survived and resisted white colonization and genocide and continue as a people to this day. Theirs is not a history of decline. Their work preserving and forwarding their culture, traditions, language, religions, and struggle for rights and land continues.

Notes

Special thanks to Bonnie Maxwell of the Friends of Carroll County Parks for sharing her newspaper research. Newspaper articles cited here are courtesy of Maxwell unless otherwise noted. Copies are available in the IHB marker file.

[1] “Trees Half Century Old Still Stand,” Logansport Pharos-Tribune, May 14, 1921.; “Lane of Trees at Deer Creek To Be Spared,” Logansport Pharos-Tribune, December 8, 1939.; “Deer Creek Road Corduroy Found at Taylor Fouts Place,” Logansport Pharos-Tribune, September 1, 1939.; Correspondence between Bonnie Maxwell, Joe O’Donnell, Tim Eizinger, and Lenny Farlee, submitted to IHB December 28, 2020, copy in IHB file.

[2] “Second State Road to Come in for Paving,” Logansport Pharos-Tribune, November 13, 1924, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.; “Lane of Trees at Deer Creek To Be Spared,” Logansport Pharos-Tribune, December 8, 1939.

[3] “Lane of Trees at Deer Creek To Be Spared,” Logansport Pharos-Tribune, December 8, 1939.; “Lane of Trees at Deer Creek To Be Spared by State,” Logansport Pharos-Tribune, December 16, 1939.; “Halt Cutting of Sycamores Along Route 29,” Logansport Pharos-Tribune, March 18, 1963.; “Governor Save 66 Sycamores,” Logansport Pharos-Tribune, March 19, 1963.; “Sycamores to Get Historical Marker,” Logansport Pharos-Tribune, April 4, 1963.; “Plant More Sycamores on Road 29,” Logansport Pharos-Tribune, April 4, 1963.

[4] “Historical Society Hears Research Report,” Hoosier Democrat, December 3, 1970.; Letter to the Editor, Hoosier Democrat, November 25, 1971.; Carroll County Comet, November 7, 1979.; Dennis McCouch, “Save the Sycamores” Carroll County Comet, November 7, 1979.; “Sycamore Row Petitions,” Carroll County Comet, January 16, 1980.; Von Roebuck, “Carroll County Landmarks to Remain Intact,” Logansport Pharos-Tribune, December 1, 1983.; “Bridge Work to Cause Deer Creek Detour,” Logansport Pharos-Tribune, June 7, 1987.

[5] Eric Foner, Who Owns History?: Rethinking the Past in a Changing World (New York: Hill and Wang, 2002), xvi.