With a staff of over 155 and over 170 volunteers, today’s Fort Wayne Visiting Nurse is a far cry from its humble beginnings. In 1888, a group of Fort Wayne women organized the Ladies Relief Union with a mission to “help the sick poor of Ft Wayne.” Calling themselves the Visiting Nurse Committee, they soon discovered a link between poverty and disease. Dr. Jessie Calvin, a Fort Wayne sanitation and indoor plumbing pioneer, encouraged women’s church groups to raise money for a qualified nurse that could meet community needs.

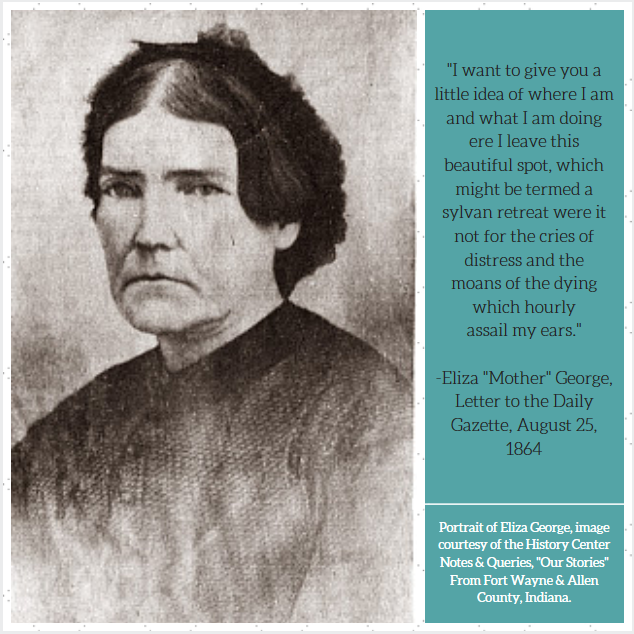

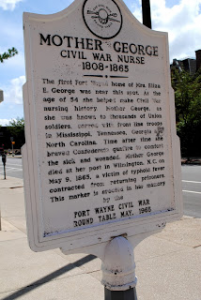

Prior to the 1860s, nursing was “typically considered a domestic responsibility provided in the home by family members.” Nursing as a profession evolved after the Civil War, when women gained experience caring for wounded soldiers. Historian Clifton J. Philips noted that in the post-war period, women’s religious orders were “especially active in establishing hospitals in an attempt to extend to the general public, and the poor in particular, some of the services formerly rendered to sick and wounded soldiers.” As hospitals materialized, so too did nursing groups and training programs. By 1897, The Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette noted that “modern nurses” wished to “be given her proper position as a skilled assistant in serious illness.”

The paper added that:

The daily or visiting nurse is a recent development of modern nursing and meets the needs of many people who find it inconvenient to have a nurse stopping in the house and requiring more or less attention from servants perhaps already overtaxed. The visiting nurse comes in for an hour or so every day to perform those services for which her skill is needed.

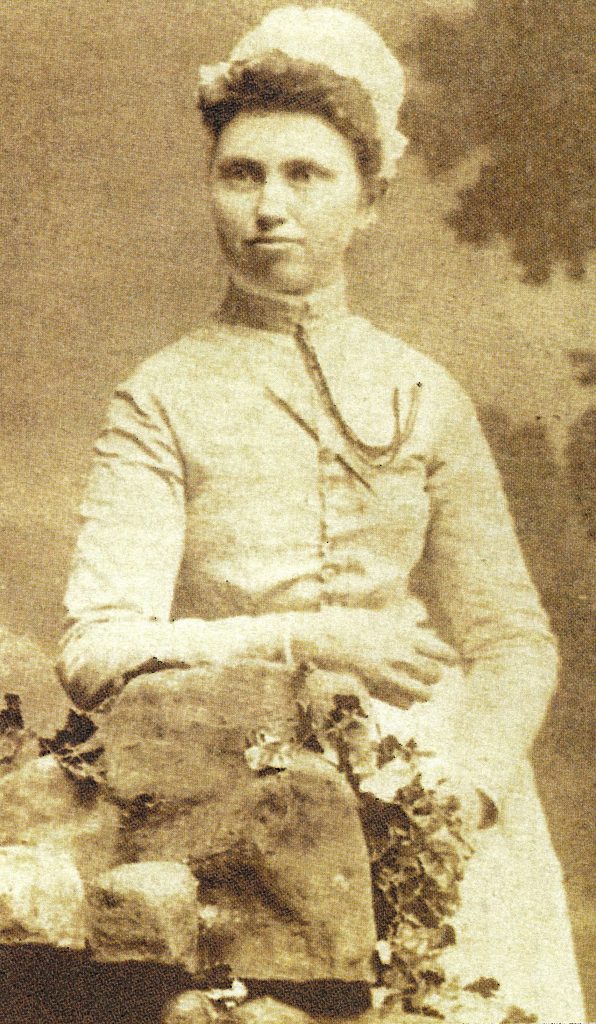

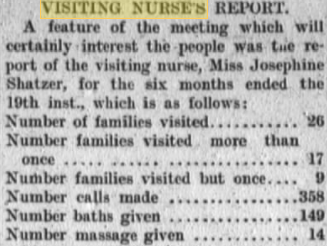

On March 1, 1900, an organizational meeting was held in Fort Wayne and the Visiting Nurse League became a reality. At a salary of $10.00 a week, Josephine Shatzer was hired as the League’s first nurse. During harsh weather she took a trolley, but normally she could be seen making her rounds on her bicycle. Regardless of transportation, it was clear that she wasted no time. On her first day she saw six patients. Next she established a baby milk station at First Presbyterian Church, instructing new moms how to prepare formula.

She also volunteered at free immunization clinics, bathed patients, delivered meals, changed bedding, dressed wounds, cared for the elderly and ill in their homes and endeared herself to all she served. At the end of her first year she had made hundreds of calls, utilizing supplies donated by local churches, relief societies, and drug stores. For those patients who could pay, the charge of a one-hour visit was fifteen cents.

The Fort Wayne Daily News praised the program in 1900, noting that the league “found favor with all classes of people” and that visits to the “sick poor” conveyed not only “help and benefit, but hope and good cheer to every member of the family.” In 1913, the Public Health Nursing Association appointed a visiting nurse to serve African American patients at the Flanner Guild. Dr. Calvin continued to guide the League, through the years of World War I and the 1918 flu epidemic, which took the lives of 3,266 Hoosiers.

By 1919, a nurse named Dixon had reached a salary of $100.00 a month. League expenditures in 1920 stood at $1,300 annually and in 1922 the Community Chest offered its support. Insurance companies began to hire nurses from local visiting nurse groups to assess policyholders who were ill, and paid the League seventy-five cents a visit. By 1923, the League reorganized and served in an advisory, instructional health teaching capacity. The Great Depression wrought poor health conditions: eight nurses made over 29,000 visits to 4,477 patients. One made 3,255 orthopedic visits to 104 crippled children, many of whom were victims of polio. Sisters of Saint Joseph Hospital provided free hospitalization in the pediatric ward for those who could not pay. In the 1940s, World War II increased demands for nursing schools to produce eligible Nurse Corps candidates.

In 1954, the agency changed its name to Visiting Nurse Service, Inc. By 1956, it undertook a program that cared for stroke victims in their homes, which served to collect data on medication, exercise, loss of function and the need for expanded therapy service. By 1962, the agency’s director Eva Rosser introduced a State Board of Health-funded program that focused on treating the chronically ill in their homes, instead of a hospital or nursing home. Later the group provided care as home health aides and the agency became certified for Medicare on July 1966.

With certification came additional paper work. According to History of Visiting Nurse, by 1983, “a record number of visits for a single month occurred (2,200), due to earlier hospital releases and greater technology used in the home.” During this period, the glucometer was used for the first time, registered nurses were trained to perform phlebotomy services, and around-the-clock care was made available for all patients. In 1984, Medicare Hospice Benefit became available and Visiting Nurse Service merged with Hospice of Fort Wayne, Parkview, and Lutheran Hospices. The agency introduced computerized billing and, by the end of the decade, services for the frail and disabled. By 1990, Hospice service visits totaled 38,177, a forty percent increase over previous months.

History of Visiting Nurse noted that in 1990 the agency moved to the “Moellering Unit of the nearly vacant former Lutheran Hospital.” In 1995, the 1984 merger dissolved and Visiting Nurse Service and Hospice became a free standing agency. By February 2001, a new Hospice Home facility opened and in 2006 a building expansion added patient rooms. In 2011, nurse practitioners joined the staff and the “Watchful Passage” program began, in which trained volunteers remained at patient’s bedside during the last few days of life. In 2018, Visiting Nurse staff and volunteers can proudly stand tall celebrating 130 years of community service.