While conducting interviews for the Indiana Legislative Oral History Initiative, I discussed with former Indiana state legislators quite a bit about the ins and outs of state politics. Our conversations covered topics like how legislators find themselves in politics, how the Indiana General Assembly has evolved over the years, and how elections are won and lost. Another interesting thing I learned, though, was how former legislators perceived of the general public during their time in office. In fact, during interviews I often asked former legislators about what they think the general public does not know about the Indiana General Assembly, as well as what they should know. Over the course of many interviews, I received a variety of answers. However, several important themes emerged, which some could argue, reflect a problematic trend for the State of Indiana.

For starters, the majority of former legislators that I interviewed told me point blank that the average Hoosier knows nothing or very little about the Indiana General Assembly and how it operates. Former Democratic Senator Thomas Teague, who served in the Indiana Senate from 1971 to 1978 and was the Senate Majority leader, stated the following when asked what the public does not know about the Indiana General Assembly: “Well, that would take about a library full . . . I don’t think the public knows very much at all about it. Maybe they don’t care. I think some do.” This belief was echoed by former Republican Representative Stephen Moberly, who served in the Indiana House of Representatives from 1973 to 1990 and said “Well, they don’t know a lot about it…it’s a pretty superficial understanding of government, which is a shame.” This is obviously a big statement to make in regard to the Hoosier population and one that needs to be taken seriously, as it certainly does not bode well for our democracy and our ability to effect change in our state. Additionally, this lack of awareness limits our ability to hold legislators accountable for policies we may not like as citizens.

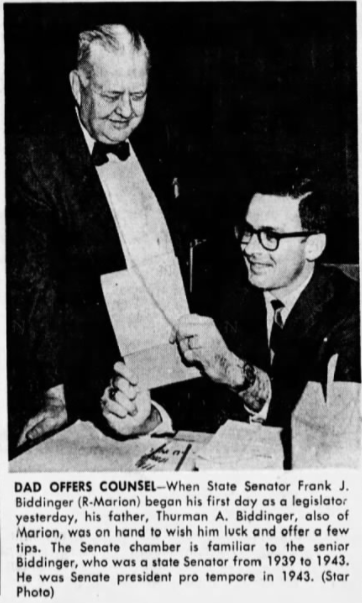

What exactly do Hoosiers not know about state government? First, interviewees noted that many people confuse state legislators for members of the U.S. Congress. This was pointed out by Indiana State Senator Frank Biddinger, who served from 1967 to 1969. He recounted the following story: “I would be at home, on a weekend, and . . . almost always, people would say to me, well, aren’t you supposed to be in Washington? They all thought I was a U.S. senator, I guess—they didn’t know the difference between a state senator and a U.S. senator.”

William Vobach, a Republican senator who served from 1983 to 1990, pointed out that because the public often conflates state legislators with U.S. lawmakers, there is an “idea that you have a staff that can run around and fix things and take care of agency problems…We haven’t got any of that.” He added that “there was just not understanding that we weren’t there all the time if something came up in the summer or something, you know? That, ‘why can’t you just go over and do it?’ [mentality].” This lack of understanding about basic civics and the functioning of state government is not relegated to Indiana. Recently, the Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation published a survey concluding that two-thirds of Americans couldn’t pass the test immigrants take to become U.S. citizens. This is an alarming fact, considering test-takers are asked to name various ways to participate in democracy.[1]

Former legislators also felt not enough citizens understand the nuances of government and how complex it is to get a bill passed into law. This was highlighted by former Republican Senator Farrell Duckworth, who served in the Indiana Senate from 1981 to 1984. He said:

They don’t realize what it takes to get a bill passed. They just don’t realize that . . . All of the hearings and everything to get the bill through and then get it kicked back in your face from the other house and have to go through it again or it completely dies and next year you’ve got to bring it back again. They don’t understand that. They think we just go up there and write the bills and that’s it. And get a big check [chuckles]. You’d be surprised how many people think that.

This observation was reiterated by former state legislators. This fact is unsurprising; if most Americans can’t pass a basic civics test, it’s unlikely they understand the complex process of how a bill becomes a law.

Additionally, a political majority—or even supermajority—does not ensure the passage of a bill. Recently in Indiana there has been disagreement within the Republican party, specifically between the Indiana General Assembly and Governor Eric Holcomb. The controversy centers around the ability of the governor to declare a state of emergency, without the intervention of the Indiana General Assembly.[2] Essentially, a Republican in the House authored a bill that would allow the Indiana General Assembly to convene for an emergency legislative session, in the event that the governor declares a state of emergency. The process of getting this bill passed into law proved incredibly complicated.

To summarize, after being authored it was sent to the House Committee on Rules and Legislative Procedures and passed through committee. Then it was sent to the House floor for a vote and was passed by the Indiana House of Representatives. Next, it was sent to the Indiana Senate’s Committee on Rules and Legislative Procedures, where it passed committee and was sent to the Senate floor for a vote. On the Senate floor, two amendments were made to the bill before it was finally passed by the Senate. As a result, it was sent back to the House, which disagreed with these amendments. Thus, it was then sent to the conference committee where leaders of the Indiana House and Senate get together to make agreements on bills in which they disagree. Finally, a conference committee version of the bill was agreed on and sent to the Governor of Indiana, who then vetoed it. In turn, the bill was sent back to the Indiana House and Senate, which voted to overrule the governor’s veto, which officially made the bill law. But, it is still technically not over yet because now the Governor of Indiana is suing the Indiana General Assembly over the legality of the law.[3]

This recent event perfectly highlights how complex the legislative process is and why many Hoosiers, as well as Americans in general, may not quite grasp the ins and outs of how bills become law. And this is only a simplified version of the events. There are many other complexities of how bills become law because there are so many ways a bill can be killed or passed into law due to various legislative tactics. Republican Senator Robert Meeks, who served from 1983 to 1990, described the sometimes gritty legislative process:

Makin’ laws is like makin’ sausage. Doesn’t look good. And you know, General Assembly’s— the legislature was created to take the fighting off the streets and move it into a confined area called the chambers. That’s why it was done, take it off the streets and bring it in here. That’s exactly the way it was. So what goes on in there, in those meetings is generally not general knowledge of the public, they shouldn’t know about all that. Not that it’s bad, but it’s just that it’s sausage.

Conversely, Democratic legislator Earline Rogers noted that while there could be conflict among lawmakers, she told ILOHI that she doesn’t think the public recognizes “the camaraderie that’s there.” Political differences might complicate legislation, but “there’s a bond that political parties just can’t break up,” like the period when she and Republican colleague Tom Wyss were both caring for loved ones diagnosed with cancer.”

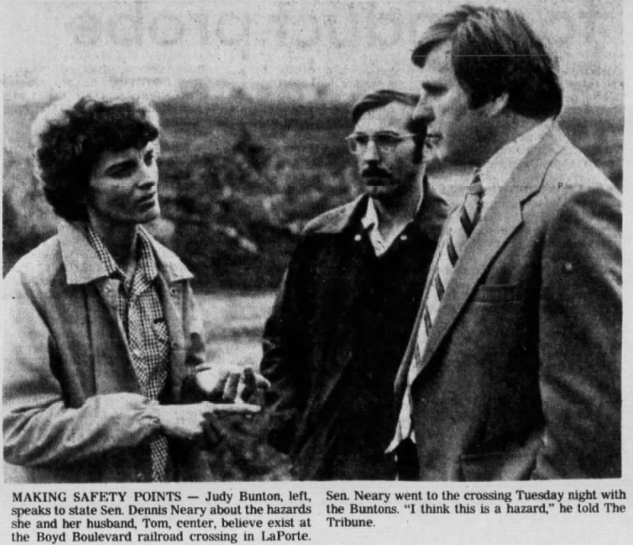

The last and perhaps most important thing many legislators wanted Hoosiers to know: don’t hesitate to contact your legislator. As former Indiana Senator Dennis Neary, who served in the Indiana Senate from 1976 to 1992, argued:

They need to know that their voice does count, and legislators will listen to them. They won’t always agree with them, but they will listen to them. And the more legislators hear from their constituents, the more they will react on an issue . . . that the person thinks is important.

This may seem like a basic idea, but many Hoosiers and Americans are actually quite passive politically, and don’t seem to be as interested as they could be in employing their political voices. Rep. Charlie Brown, a Democrat who served from 1982 to 2018 and member of the Indiana Black Legislative Caucus, described in practical terms how his constituents made their voices heard. He noted that during and after session, he attended public forums and mailed out surveys asking what legislative issues constituents wanted to pass. Rep. Brown noted that the information was “compiled by the staff and then it shows us the issues that are most important to the constituents back home.”

Indiana’s former legislators seem to emphasize that not enough is being done by everyday Hoosiers to nurture the health of the State of Indiana. Citizens should strive to be more politically active. Political passiveness towards state government may seem harmless, but bills that could one day affect your life, for better or worse, are being passed every session. We must remember that many around the world are fighting just for the opportunity to have a fraction of the amount of political influence that Hoosiers possess. The enactment of laws may not seem to be the most pressing issue in our day to day lives, but it has the potential to dramatically affect us whether we want it to or not. So it is critical to look into potential legislation and to weigh in by bringing your concerns and experiences to lawmakers. After all, they work for us.

Sources:

[1] Patrick Riccards, “National Survey Finds Just 1 in 3 Americans Would Pass Citizenship Test,” October 3, 2018, accessed Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation.

[2] Tom Davies, “Indiana Lawmakers Override Governor’s Emergency Powers Veto,” April 15, 2021, accessed AP News.

[3] Indiana House Bill 1123, passed April 15, 2021, accessed LegiScan.

The Associated Press, “Judge Letting Gov. Holcomb Sue Indiana’s Legislature to Block Emergency Law,” July 6, 2021, accessed WTHR.