A caravan of automobiles, expertly commanded by Evansville women, arrived at polling stations on November 2, 1920. That day, Hoosier women exercised their right to vote for the first time in history. In their decades-long work for enfranchisement, many women found their political voice, gained self-assurance by withstanding public scrutiny, and mastered the art of grassroots mobilization. This served them well on Election Day, when the Evansville Courier reported that “One girl had been held up by some of her boy friends who were attempting to remove the political insigna [sic] from her car, but she was demonstrating the fact that this day had women came into their own and was defending her car and her party valiantly. From somewhere another young amazon came to her rescue. It was a good natured scrap but the girls won.”

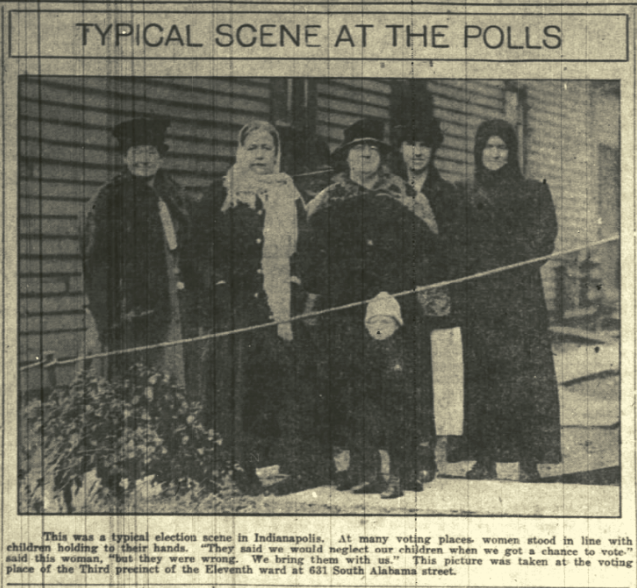

Indeed, the activism of the suffrage movement carried over to ballot box. In Evansville, women in “conspicuously labeled” automobiles ensured that no sister was left behind and picked them “up off the streets and hauled to their respective voting places, irrespective of politics.” Hoosier women invoked the communal spirit of the homefront during World War I, when they organized for war work and suffrage. Munster women drove to women’s houses to watch their children, while the “mistress of the house was taken to the polls.” In Evansville, as with cities across the country, “Many women took turns with her neighbor in minding the children while the other voted. That plan worked nicely. The political women workers also took charge of the children while mothers voted.”

Some working women in Evansville arrived at the polls early, so as to miss as little work as possible. Other women, like those employed by the Fendrich Cigar Factory, were given a “half holiday,” so they could exercise their newfound right. On the northside of the city, women went from “house to house,” arranging for housewives to vote earlier in the day. This would “clear the way for factory workers who could vote only between 5 and 6 o’clock.”

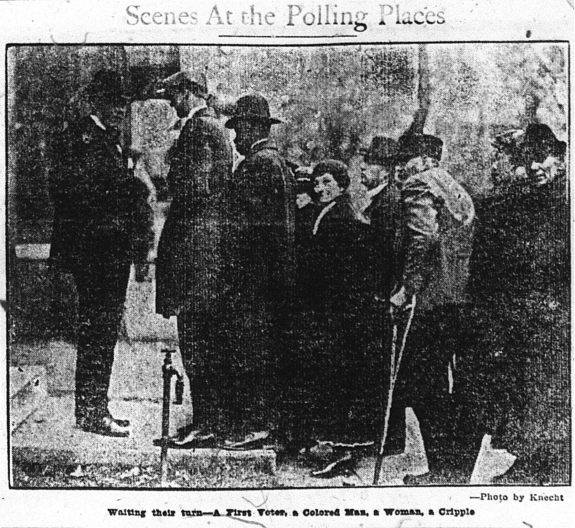

Once at the polls, women capitalized on the long-awaited opportunity. In Noblesville, papers reported that it was common for women who encountered long voting lines to insist that men let them vote first. The men obliged. Women at one precinct demonstrated passion equal to that of male voters, as they “became involved in some pretty heated arguments over politics,” but quickly disengaged when polling officials intervened. Muncie women, especially those who worked, voted early and the Star Press reported that “Intense interest was manifested in the campaign issues by the women clerks in many uptown stores and there were many heated debates overheard by those so fortunate to be far back in line awaiting their turn to vote.” As with Noblesville, the Muncie debates dissipated without incident.

Mrs. F. T. Reed, of Indianapolis, wouldn’t let a car accident, which left her “badly bruised and shaken,” keep her from casting her vote. After an ambulance took her home, she rested for a few hours before returning to the polls. Inspector of the Third Precinct of the 18th Ward, Charles H. Taylor, observed that women voted “intelligently, quickly, and manifested more interest in the election than the men.” In Gary, mothers hurried to the polls in the early morning. The Gary Evening Post remarked, “She didn’t stop outside to chat though, just hurried back home and resumed her management of a successful home while all the silly talk about mother neglecting her home and children to vote evaporated.”

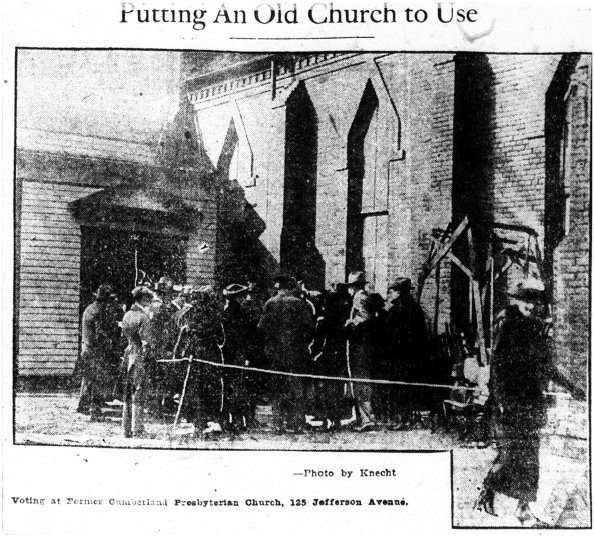

Some Hoosiers marveled that women needed little help with the process of voting. In Indianapolis, “Contrary to expectations, women voters did not become confused when they reached the voting booths.” Far from meek or bewildered, one Evansville woman cast her vote so fervently that she ripped the handle off of the machine. The Noblesville Ledger remarked that Hamilton County women, some of whom voted in their “kitchen apparel” so as not to waste any time, “walked into the precincts as if they had been voting all of their lives.” The Tipton Daily Tribune attributed the success of local women in voting “to the interest they took in learning to vote. The voting schools in Tipton and over the county were filled each day with women trying out the system and receiving instructions.”

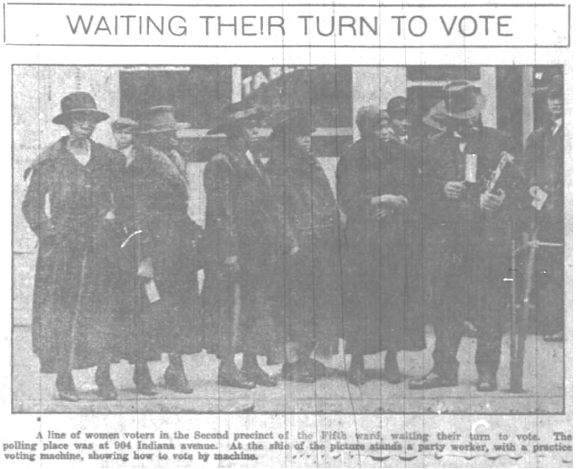

African American women, who had been so integral to obtaining the vote, too turned out in droves. The Indianapolis News noted that in some parts of the city “colored women swarmed to the polls in greater numbers than men.” According to historian Jill Weiss Simins, party organizers arranged for a cannon blast to rouse residents of the Fifth Ward, who lived in predominantly-Black areas like Indiana Avenue and Ransom Place, to ensure that no voters overslept on Election Day. Weiss Simins vividly depicted the moment:

The Black women of the Fifth Ward’s Second Precinct dressed up in high-heeled shoes and lace up boots, donned coats with wide collars and fur edging, and sported a variety of hats trimmed with satin ribbons. They made their way to 904 Indiana Avenue, walking past several shops, a large dry goods store, and a doctor’s office, and lined up outside ‘Wm. D. Chitwood Fruits,’ a large market that served as their polling place.

Like many white women voters, they endured long lines in the bitter cold and generally voted for the Republican Party. Unlike white voters, their livelihood and well-being depended much more on the results of the election, as Indiana Equal Suffrage Branch #7 president Carrie Barnes contended, “We all feel that colored women have need for the ballot that white women have, and a great many that they have not.”*

The women who staffed the polls displayed the same grit as female voters. In Elwood, women workers did whatever was asked of them, “holding the poll books in the chill November air.” In Culver, Republican women instructed voters how to properly mark their ballots, occasionally ducking into tents equipped with stoves to keep them warm. Hoosier reporters across the state commended the efficiency with which women worked the polls. The Elwood Call-Leader wrote, “The Republican and Democratic chairmen owe much to the efforts of the woman who entered the campaign with a commendable spirit and their participation lent dignity all along the line.”

While Hoosier women suffered no fools at the polls, their presence also produced a kinder, more dignified election than of those past. The Evansville Courier noted that “At the polls there was nothing but courtesy and kindliness, showing that the softening influence of a woman’s presence was felt even there.” The Richmond Item reported that the barbs thrown at voters whose candidates lost were noticeably gentler and that no brawls erupted due to the attendance of women. Even the ballots were cleaner, as the Tipton Daily Tribune reported: “All the ballots marked by the ladies were folded with an exactness and neatness which could easily be detected when the ballot boxes were opened.”

On the evening of November 2, Hoosier women, likely exhausted yet proud, waited as their ballots were counted. Evansville residents watched returns projected from stereoptican slides onto a twenty-four foot wide screen hung from a downtown building. In Muncie, crowds watched returns projected by the Star Press on a screen hanging from the YMCA building. The 1920 election experienced the largest voter turnout in the state’s history, with 71,000 of 76,000 registered women casting their vote in Indianapolis. The Black vote in Indiana, an estimated 45,000 voters, played a large part in the national election and shifted “the balance of power,” according to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). With the victors declared, many women held election parties at sites like the Victoria Hotel and the mayor’s office in Gary.

The 1920 election was significant not only because women skyrocketed voting rates, but because they changed the nature of elections. Hoosier women demonstrated how to conduct an election not only efficiently, but respectfully and with kindness. Evansville Democrat Walter Wunderlich said he had never seen “anything like it before in politics” and that “I wouldn’t go back to the old conditions for anything. I haven’t heard a quarrel all day.” The ingenuity women displayed in getting their fellow voters to the polls, regardless of party affiliation, was truly American. The spirit of Indiana’s suffragists lives on through the League of Women Voters, which formed with the ratification of the 19th Amendment and continues to ensure that voters are informed, empowered, and show up for the democratic process.

* While some southern states disenfranchised Black women through state election laws and voter intimidation, Black women in Indiana faced no legal obstacles to voting.

Sources:

*All newspaper articles accessed via Newspapers.com unless otherwise specified.

“Clean Sweep is Made,” Star Press (Muncie, IN), November 3, 1920, 4.

“Did You Hear That,” The Times (Munster, IN), November 3, 1920, 1.

“Election Crowd Good Natured,” Richmond Item, November 3, 1920, 2.

“Election is Quietest Ever,” Evansville Courier, November 3, 1920, 11, Indiana State Library microfilm.

“Indiana Women Wear Boudoir Caps to Elections,” Gary Daily Tribune, November 2, 1920, 1, Indiana State Library microfilm.

“Less Than 5,000 of 76,000 Women in County Fail to Vote,” Indianapolis Star, November 3, 1920, 11.

“Made Fine Showing,” Tipton Daily Tribune, November 3, 1920, 1.

Anita Morgan, “We Must Be Fearless:” The Woman Suffrage Movement in Indiana (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society, 2020) , 204.

Jill Weiss Simins, “A ‘Record of Protest Against Prejudice’: Black Hoosier Women Vote in the 1920 Election,” Indiana Historical Bureau (2020).

“The Election,” Culver Citizen, November 3, 1920, 1.

“Women Ballot Early and Fast,” Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette, November 3, 1920, 1.

“Women Filled All Requirements in Election Day Duties,” Call-Leader (Elwood, IN), November 3, 1920, 1.

“Women Had Good Time at Election,” Noblesville Ledger, November 3, 1920, 1.

“Women Hurry to Polls to Cast Ballots,” Gary Evening Post, November 2, 1920, 7, Indiana State Library microfilm.