This post is dedicated to Tom Flynn—freethinker, friend, and keeper of the Ingersoll flame.

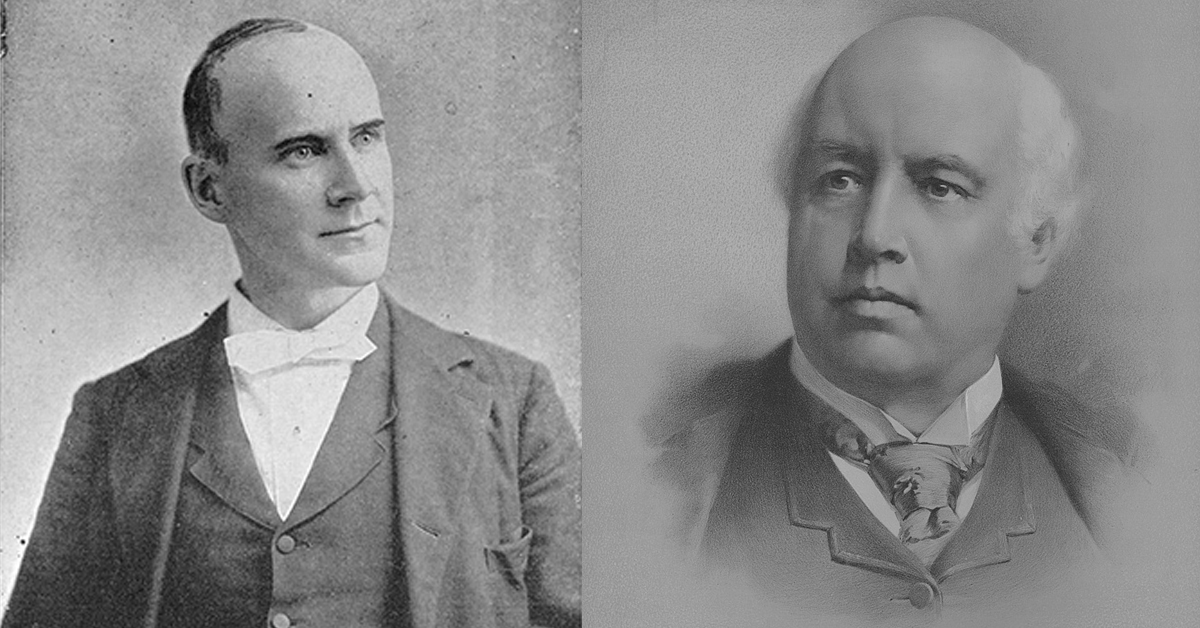

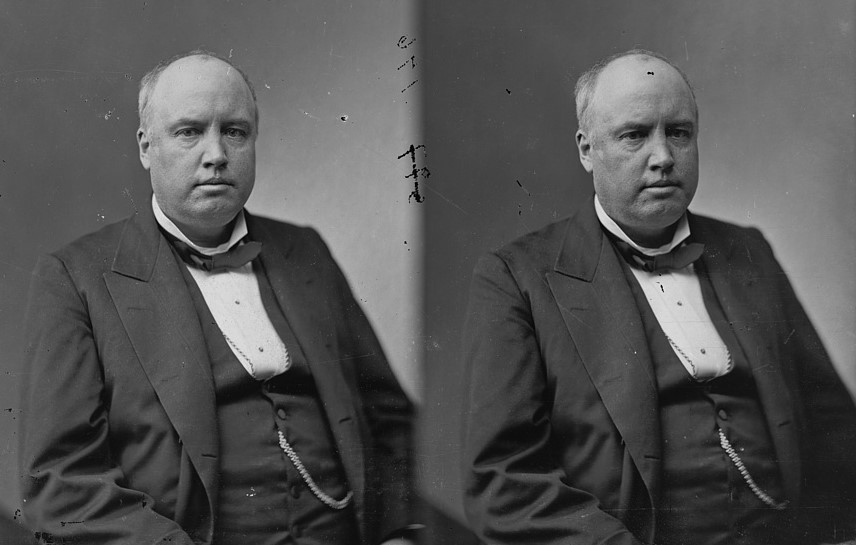

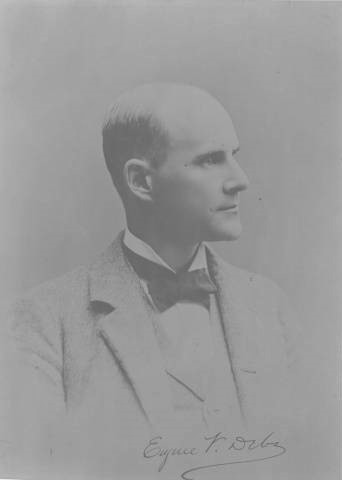

On July 22, 1899, Hoosier Eugene Victor Debs, a radical labor organizer and the future socialist party candidate for president, published a tribute to one of his biggest influences and close friends—the orator and freethinker Robert Green Ingersoll. Known as the “Great Agnostic” for his decades-long public critique of organized religion, Ingersoll became the leader of the “Golden Age of Freethought” in the United States, a movement dedicated to secularism that began after the Civil War and ended around World War I. His death on July 21, 1899, at the age of 65, left an irreplaceable void in the hearts of many who saw Ingersoll as the leader of a new rationalist awakening in America.

In his tribute to Ingersoll, printed in the Terre Haute Gazette and later in the Social Democratic Herald, Debs reflected on their decades-long friendship and the lasting impact the freethinker had on his life. He wrote:

For 23 years it has been my privilege to know Colonel Ingersoll, and the announcement of his sudden death is so touching and shocking to me that I can hardly bring myself to realize the awful calamity. Like thousands of others who personally knew Colonel Ingersoll, I loved him as if he had been my elder brother. He was, without doubt, the most lovable character, the tenderest and greatest soul I have ever known.

He also noted the amount of charity work Ingersoll did, both for organizations and for individuals, such as a woman he aided after the financial collapse of her father and abandonment by her church. “Such incidents of kindness to the distressed and help to the needy,” Debs observed, “might be multiplied indefinitely, for Colonel Ingersoll’s whole life was replete with them and they constitute a religion compared with which all creeds and dogmas become meaningless and empty phrases.”

Later, on January 17, 1900, Debs wrote to Ingersoll’s publisher C.P. Farrell that “I have never loved another mortal as I have loved Robert Ingersoll, and I never shall another.” While this language may seem a bit saccharine for us today, Debs meant every word of it. From his initial meetings with Ingersoll as a young man in Terre Haute, Indiana to the Great Agnostic’s defense of him during the Pullman railroad workers strike of 1894, Eugene Debs always felt a deep kinship with the heretical orator. While they took different spiritual tracks—with Ingersoll a dedicated agnostic and Debs a social-gospel Christian—both saw the importance of caring for others in this life, despite what might come after, and believed in the power of human reason as a vehicle for transcending outmoded superstitions. Debs learned the power of effective oratory from Ingersoll, routinely citing him as one of his biggest rhetorical influences. Ingersoll also had views on labor and capital that went far beyond the traditional liberalism of his day, something that likely played a role in the radicalization of Debs. As such, their unique friendship left a lasting imprint on American life during the turn of the twentieth century.

They first met in the spring of 1878, after Debs invited Ingersoll to give a lecture to the Occidental Literary Club in Terre Haute, an organization that the former helped organize. The Terre Haute Weekly Gazette reported on May 2, 1878 that Ingersoll’s oration the previous evening was on the “religion of the past, present, and future” and noted that “Mr. Ingersoll was introduced by Mr. E. V. Debs, in well chosen and well delivered words.” Years later, in his “Recollections on Ingersoll” (1917), Debs reflected on his first encounter with the legendary orator. In fact, the lecture that Ingersoll gave that evening, according to Debs, was one of his most important, “The Liberty of Man, Woman, and Child.” In it, Ingersoll excoriates those who held humanity in the bondage of superstition and called for freedom of intellectual development. As he declared, “This is my doctrine: Give every other human being every right you claim for yourself. Keep your mind open to the influences of nature. Receive new thoughts with hospitality. Let us advance.” Debs was amazed by this speech. Writing decades later, “Never until that night had I heard real oratory; never before had I listened enthralled to such a flow of genuine eloquence.” Ingersoll’s words, which “pleaded for every right and protested against every wrong,” galvanized the budding orator and political activist.

Also in 1878, Ingersoll used his considerable speaking talents towards another issue of grave importance: the condition of labor. While it would be too much to say that Ingersoll was a socialist like Debs, he was nevertheless a socially-conscious liberal Republican who understood the inequities between workers and owners in a capitalist society. In a speech entitled “Hard Times and the Way Out,” delivered in Boston, Massachusetts on October 20, 1878, Ingersoll laid out his views on the subject. While he reiterated his belief that “there is no conflict, and can be no conflict, in the United States between capital and labor,” he nevertheless chastised the capitalists who would impugn the dignity and quality of life of their laborers. “The man who wants others to work to such an extent that their lives are burdens, is utterly heartless,” he bellowed to the crowd in Boston. He also called for the use of improved technology to lower the overall workday. Additionally, in a passage that could’ve been composed by Eugene V. Debs decades later, Ingersoll declared:

I sympathize with every honest effort made by the children of labor to improve their condition. That is a poorly governed country in which those who do the most have the least. There is something wrong when men are obliged to beg for leave to toil. We are not yet a civilized people; when we are, pauperism and crime will vanish from our land.

This speech left a lasting impression on Debs, so much so that he quoted it at length in an 1886 article in the Locomotive Firemen’s Magazine calling for the eight-hour workday. It is safe to say that Ingersoll’s own progressive views on labor influenced Debs’s own labor advocacy, especially during his time leading the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and co-founding the Industrial Workers of the World (I.W.W).

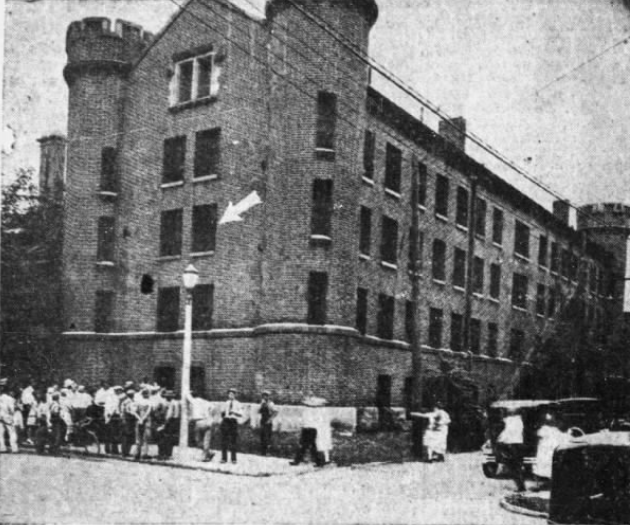

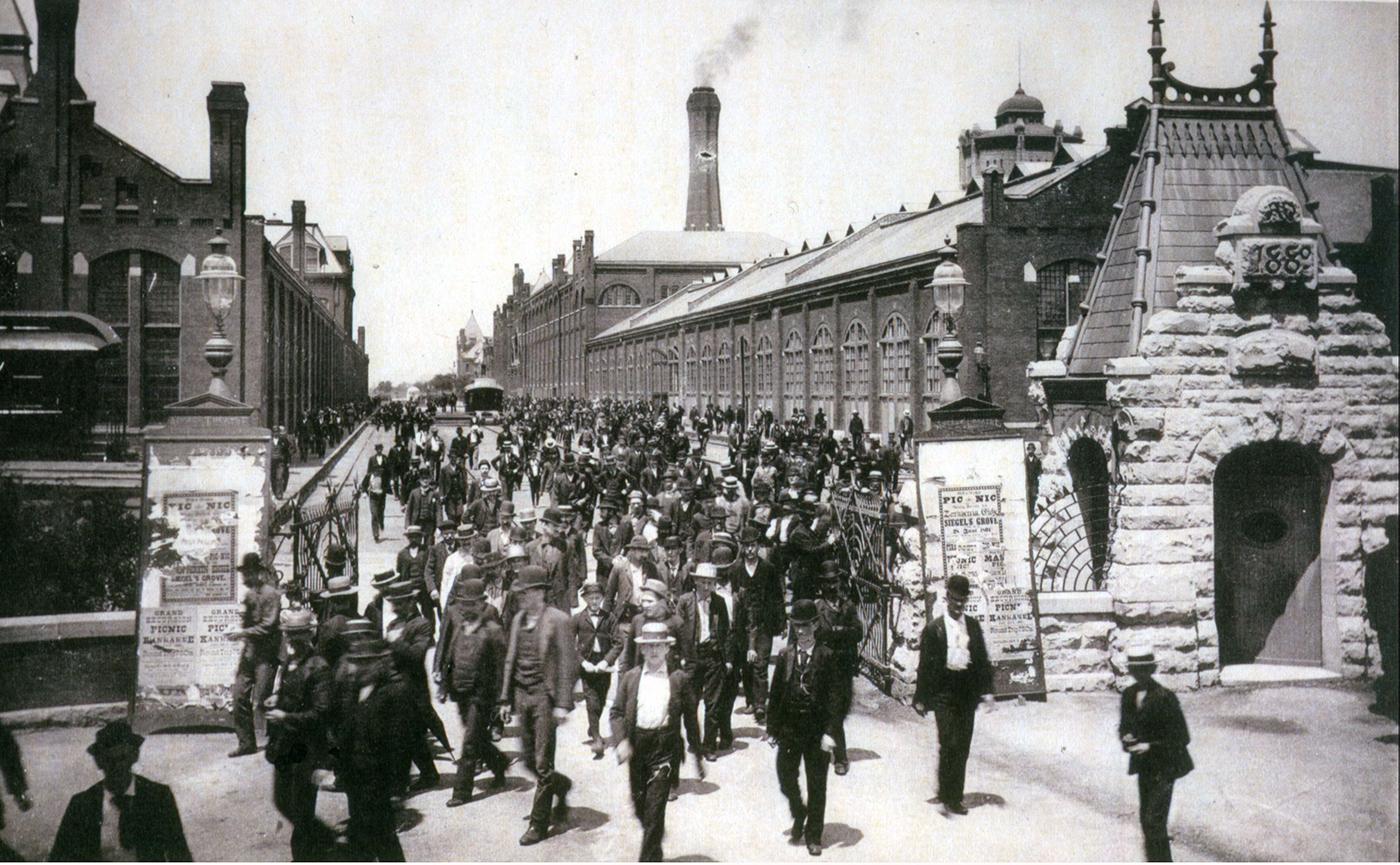

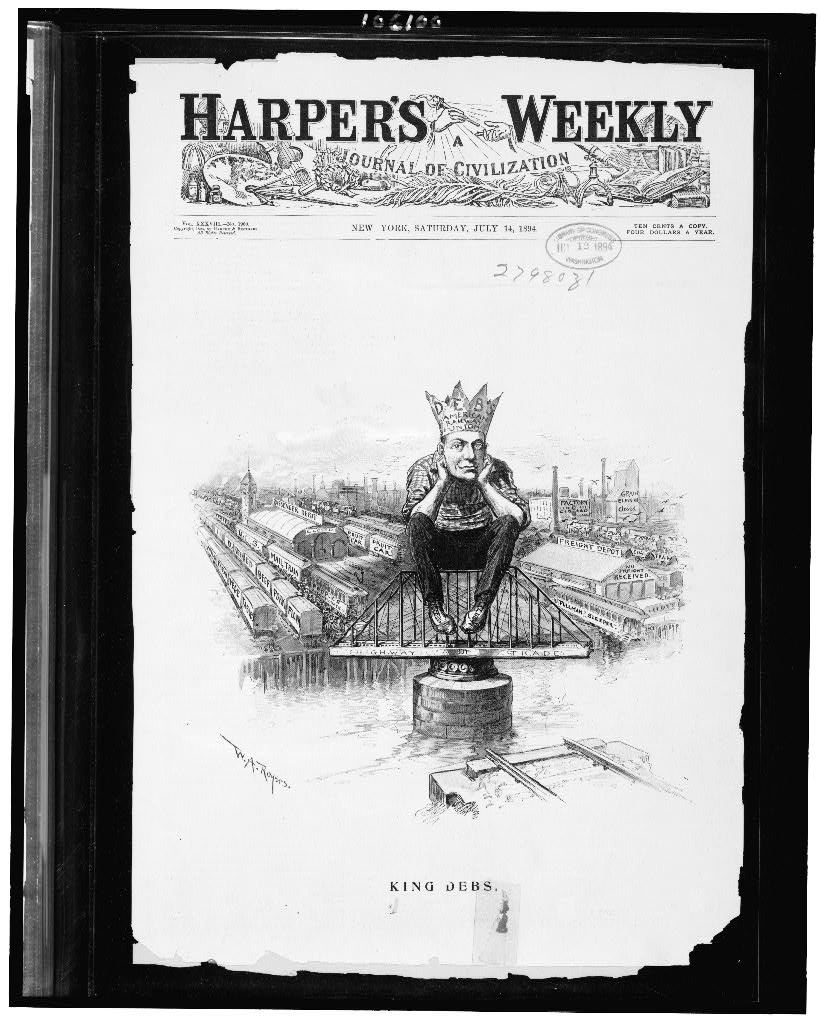

Years later, in 1894, Eugene V. Debs and the American Railway Union (ARU) led a massive labor strike against the Pullman Palace Car Company in the outskirts of Chicago. Approximately 2,000 employees walked off the job in May, demanding an end to the 33 1/3% pay cut they took the year prior. When the strikes escalated into violence, largely due to the aggressive tactics of the Chicago police, the United States Court in Chicago filed an injunction against Debs and the ARU. The injunction claimed that Debs, as head of the ARU, violated federal law by “block[ing] the progress of the United States mails,” the Indianapolis Journal reported. Debs was later arrested for his actions, using legendary civil rights attorney Clarence Darrow for his defense. Some speculated at the time that Robert Ingersoll, himself a lawyer, would defend Debs in court, but that never came to pass. Instead, Ingersoll defended Debs in the court of public opinion, when the press reported his previous treatment for alcoholism in an effort to discredit his cause.

An article in the July 9, 1894 issue of the Jersey City News reported that Dr. Thomas S. Robertson treated Debs in 1892 for “neurasthenia” and “dipsomania,” terms used in the era to describe anxiety due to spinal cord injury and alcoholism, respectively. To help his friend, Ingersoll had written a letter of introduction for Debs to Dr. Robertson, as he had used the physician’s services before. The article quotes Dr. Robertson at length, who claimed that Debs suffered from exhaustion, which had been exacerbated by drinking, but he had improved in the two years since. When asked if Debs was of sound mind, Dr. Robertson said, “in ordinary times, yes, but he is likely to be carried away by excitement and enthusiasm.” In essence, Debs suffered from what today we might call stress-induced anxiety, which became more pronounced by substance abuse. However, it is important to note that charges of alcoholism were common in this era, and Debs might have exhibited symptoms of it without ever being intoxicated.

Sensing the intention of the press with this story, Ingersoll released a statement to the Philadelphia Observer, later reprinted in the Unionville, Nevada Silver State on August 27, 1894. In it, he stood up for his friend and the causes he fought for. “I have known Mr. Debs for about twelve years,” Ingersoll said, and “I believe, [he] is a perfectly sincere man—very enthusiastic in the cause of labor—and his sympathies are all with the workingman.” When asked about Debs’s drinking, Ingersoll pushed back on the claims, saying “I never met him when he appeared to be under the influence of stimulants. He was always in good health and in full possession of his faculties.” He also commented on the attempts at scandal in the newspapers, adding that his “testimony is important in view of gossip and denunciation that everywhere attend the public mention of the strike leader.” In one of Debs’ darkest hours, when his character and cause came under fire, Ingersoll publicly defended his friend and challenged the claims made against him. Such was the nature of their bond.

While Robert Ingersoll certainly influenced Debs on the importance of oratory and the cause of labor, he also left a profound intellectual influence on the future socialist. Early in his life, Debs developed an iconoclastic view of religion, which primed him for a rewarding relationship with Ingersoll. In conversations with Larry Karsner, published in book form in 1922, Debs reflected on the event that made him weary of organized religion. At the age of 15, Debs attended a sermon at St. Joseph’s Catholic Church in Terre Haute. The priest’s vivid descriptions of hell, with a “thousand demons and devils with horns and bristling tails, clutching pitchforks, steeped in brimstone,” completely soured him on institutionalized Christianity. “I left that church with rich and royal hatred of the priest as a person, and a loathing for the church as an institution,” Debs said, “and I vowed that I would never go inside a church again.” Furthermore, when asked by Karsner if he was a disbeliever at that time, Debs replied, “Oh yes, a strong one.”

He furthered his views on hell in a February 19, 1880 article in the Terre Haute Weekly Gazette. “I do not believe in hell as a place of torment or punishment after death,” he wrote, “. . . the hell of popular conception exists solely in the imagination.” He further argues that while the idea of hell may have served a beneficial function in the past, “as soon, however, as people become good enough to be just and honorable for the simple satisfaction it affords them, and avoid evil for the same reason, then there is no further necessity of hell.” With these words, Debs actually echoed much of what Ingersoll said on the subject in an 1878 lecture. “The idea of a hell,” Ingersoll noted, “was born of revenge and brutality on the one side, and cowardice on the other. In my judgment the American people are too brave, too charitable, too generous, too magnanimous, to believe in the infamous dogma of an eternal hell.”

While the doctrine of hell and the strictures of the church left Debs cold, he nevertheless adopted a liberal, nondenominational form of Christianity later in his life, one molded by his exposure to Ingersoll and freethought. In a 1917 article entitled “Jesus the Supreme Leader,” published in the Call Magazine and later reprinted in pamphlet form, Debs shared his thoughts on the prophet from Nazareth. Debs saw Christ not as a distant, ethereal presence, but rather as a revolutionary figure whose own humanity made him divine. “Jesus was not divine because he was less human than his fellow-men,” he wrote, “but for the opposite reason, that he was supremely human, and it is this of which his divinity consists, the fullness and perfection of him as an intellectual, moral and spiritual human being.” He placed Jesus in the same pantheon of transformative figures as abolitionist John Brown, President Abraham Lincoln, and philosopher Karl Marx.

For Debs, Christ’s appeal to “love one another; as I have loved you, that ye also love one another” was the same in spirit as Marx’s famous dictum in the Communist Manifesto: “Workers of all countries unite! You have nothing to lose but your chains. You have a world to win.” Both statements are about solidarity—of people coming together, helping one another, and fighting for a better world. In this sense, Debs interpreted Christ like many humanists and non-sectarian Christians do today—as a deeply human figure that preached love, peace, and harmony with others.

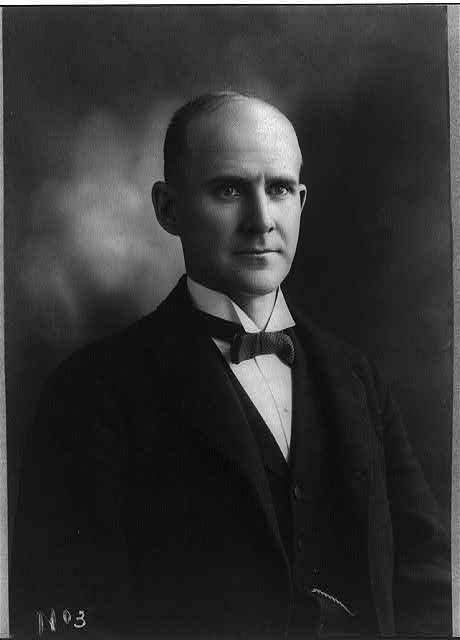

While Debs and Ingersoll did not share the exact same views on Christianity, they did share a commitment to secularism, tolerance, freethought, and social justice. Debs would parlay his knowledge from Ingersoll and others into a successful political career, running five times on the socialist party ticket and earning nearly a million votes in 1920 while imprisoned for speaking out against America’s involvement in WWI. As Ingersoll was the leader of the “Golden Age of Freethought,” Debs was the leader of the “Golden Age of American Socialism,” with thousands attending his speeches and joining socialist organizations. Despite their friendship being tragically cut short by Robert Ingersoll’s death in 1899, Debs honored the legacy of the Great Agnostic for the rest of his life. Writing in his “Recollections of Ingersoll” in 1917, Debs said:

He was absolutely true to the highest principles of his exalted character and to the loftiest aspirations of his own unfettered soul. He bore the crudest misrepresentation, the foulest abuse, the vilest calumny, and the most heartless persecution without resentment or complaint. He measured up to his true stature in every hour of trial, he served with fidelity and without compromise to the last hour of his noble life, he paid in full the price of his unswerving integrity to his own soul, and each passing century to come will add fresh luster to his immortal fame.

In studying their lives and their friendship, one might say these words for Robert Green Ingersoll could equally apply to Eugene Victor Debs.