This is Part Two of a three-part series, but also stands alone as a story of the incredible strength of the 1924 Notre Dame football team and the university’s struggle to combat prejudice in the age of the Klan. See Part One for the 1923 Notre Dame football season, context on the political strength of the Klan in Indiana, the May 1924 clashes between Klan members and an alliance of Notre Dame students and South Bend’s Catholic residents of immigrant origin, as well as the ensuing damage to the university’s reputation.

Notre Dame students returned to campus in the fall of 1924 under the looming threat that the Klan would return before the November elections. Just months earlier, in May, the Klan had been able to bait Notre Dame students into a violent confrontation. While initially embarrassing to the Klan, as they were all but driven out of town by students, the Klan’s propaganda machine was able to revise history. Using widely circulated brochures and newspaper articles, the hate group painted the students as an unruly mob of Catholic immigrant hooligans who attacked good Protestant American businessmen assembled peacefully. By fall, local Klansmen still wanted revenge for the previous spring’s humiliation, while state Klan leaders sought to show voters that they needed protection from the “Catholic menace.” Notre Dame University staff and leadership prepared for further violence and worked to rehabilitate the school’s image in the wake of the spring clash between students and Klansmen. The school needed a public relations miracle to combat the Klan’s far reaching propaganda.

University President Father John O’Hara devised a strategy for countering the negative press coverage inflicted on Notre Dame by highlighting one university program that was beyond reproach, not to mention already popular and exciting enough to draw press coverage. Father O’Hara’s inspired strategy was to put the full weight of the university behind championing its successful football team and the respectable, upright, and modest team members. The Fighting Irish football team had finished the 1923 season with only the one loss to Nebraska and a decent amount of newspaper coverage.* Much more was riding on the 1924 football team’s success. The school administration, the student body, alumni, as well as Catholics and immigrants in Indiana and beyond, looked to the Notre Dame players to show the world that they, and people who shared their religion and heritage, were proud, hardworking, dignified, and patriotic. The model team could prove the Klan’s stereotypes about Catholics and immigrants had no resemblance to reality. [1]

Father O’Hara recognized that linking the players’ Catholicism with their success on the gridiron created a strong positive identity for the university. Since at least 1921, he had arranged for press to cover the players, Catholic and non-Catholic together, attending mass before away games. He provided medals of saints for the team to wear during games and distributed his Religious Bulletin, in which he wrote about “the religious component in Notre Dame’s football success,” to alumni, colleagues, and the press. [2] According to Notre Dame football historian Murray Sperber, Father O’Hara conceived of an ambitious outreach plan for the 1924 season as a direct response to the Klan’s propaganda. In fact, O’Hara may have gotten the idea from a 1923 New York Times editorial that sarcastically reported on the reason for the Klan’s rise and extreme anti-Catholicism in Indiana:

There is in Indiana a militant Catholic organization, composed of men specially chosen for strength, courage and resourcefulness. These devoted warriors lead a life of almost monastic asceticism, under stern military discipline. They are constantly engaged in secret drills. They make long cross-country raiding expeditions. They have shown their prowess on many battlefields. Worst of all, they lately fought, and decisively defeated, a detachment of the United States Army. Yet we have not heard of the Indiana Klansmen rising up to exterminate the Notre Dame football team. [3]

This editorial and other similar articles implied that making the football team the symbol of Catholicism at Notre Dame could serve to combat the Klan in the press. In 1924, Father O’Hara created a series of press events to align with the game schedule, hoping to link the school’s proud Catholicism with the excitement of the winning team. [4] Of course, for this strategy to work, the team had to keep winning games.

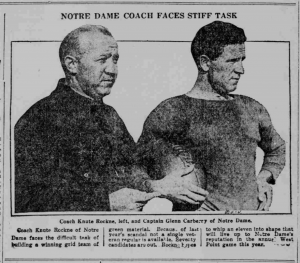

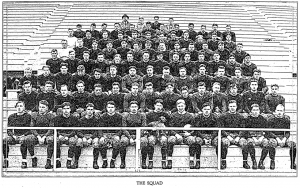

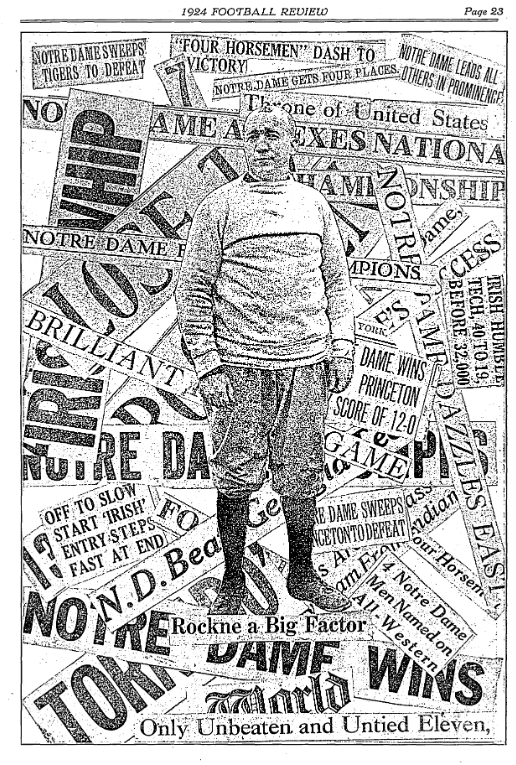

Coach Knute Rockne, who had led the Fighting Irish since 1918, had built an almost unstoppable football team by the close of the 1923 season. In six seasons, the team only lost four games. Two of these were tough losses to Nebraska where the players faced anti-Catholic hostilities. [5] In 1924, with the eyes of the nation on them, the Notre Dame team needed a perfect season. Luckily “the 1924 Notre Dame Machine was bigger and better than ever,” according to the editors of the Official 1924 Football Review. [6]

The season opened October 4, 1924 with a home game against Lombard College in Galesburg, Illinois. Coach Rockne employed a brilliant opening strategy. He started his secondary unit, called the “shock troops” who would “take the brunt of the fight” during the opening game and “wear down the opposition.” [7] Rockne then put in his main players, who most coaches would have started. This strategy meant that their opponents, in this case Lombard, would think they were holding their own against the Fighting Irish. Then the eleven regulars would show them the full force of the team. While the Chicago Sunday Tribune reported that Lombard “outplayed the second team Rockne started,” aka the “shock troops,” Notre Dame decisively beat the Illinois team 40-0. [8]

On October 11, the Irish defeated Wabash College just as handily, winning 34-0. The South Bend Tribune reported, “Notre Dame took the game easily and without much apparent effort . . . The Irish were never forced for a touchdown by that old spirit known as a fight.” [9] While Notre Dame was clearly the better team, the Tribune criticized them for being “crude and lumbering” and the play “slow and listless.” In fact, the local paper was fairly pessimistic about the upcoming games, noting that the Irish “may crumple” in the following week’s game against Army or “give way” to Northwestern. The game against Army would decide if Rockne’s 1924 team was as good as the previous season’s hype foretold. [10]

While the Fighting Irish prepared for the battle against Army, Notre Dame officials readied for another kind of clash. The Klan had declared their intention to return to South Bend 200,000 strong on October 18 – the same date as the upcoming game. They also claimed to have the support of local officials. The Fiery Cross reported:

Chief of Police Lane and Mayor Siebert have promised their support to the demonstration and the procession will be escorted by a squadron of police on motorcycles, lest their be a repetition of last May’s attack on Klansmen by Roman Catholic Notre Dame students. [11]

Notre Dame officials had no way to know if the Klan gathering was to be believed or if it was just Klan propaganda. What President Walsh did know was that he couldn’t trust city officials to protect his students. If the Klan descended on South Bend, Notre Dame would stand alone. As October 18 neared, Walsh noticed that the city was not making preparations to host a large gathering. Walsh also heard from Republican insiders that the state party was trying to quiet these kind of Klan demonstrations and distance itself (in public but not behind closed doors) from the Klan in order to not lose voters before the November election.

Drawing on this information, Walsh predicted that the rally would not happen. In fact, Indiana Republican Party Chairman Clyde Walb had forced the Klan to cancel the meeting by threatening to close the party headquarters. This would have left Republican state candidates, including those supported by the Klan, to fend for themselves for promotion and organization right before the election. [12] But the Fiery Cross continued to promote the rally, using the event to repeat their version of the clash earlier that spring. The Fiery Cross reminded its sympathetic readers:

Last May, when the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan attempted to hold a peaceful demonstration in this city, they were set upon — along with other Protestants — by Roman Catholic students from Notre Dame. They were beaten, kicked, and cursed, the women were called vile names and the American flag was trampled under foot. [13]

This was of course not what had happened (see Part One), but through continued repetition, the Klan convinced many people of their biased version of the story. Despite the Fiery Cross‘s claim that 200,000 Klansmen would take over South Bend “from morning to midnight,” they ceded to the political pressure and called off the rally. [14] Notre Dame officials and supporters must have breathed a sigh of relief. They could now return their focus to the upcoming game and all the hopes that rested on this win.

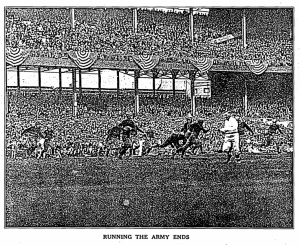

The sports media’s hype was intense leading up to the October 18th Notre Dame – Army game that would take place in New York. This press coverage was owed in part to the East Coast alumni. Several graduates were in the city drumming up support for their alma mater by feeding Notre Dame-produced press statements to New York newspapers and proselytizing at Catholic social organizations like the Marquette Club. Another factor, likely more influential, was Rockne’s decision to hire a New York Times writer for an exorbitant sum. This all but guaranteed a round of good press for the Irish. [15] All they had to do was win.

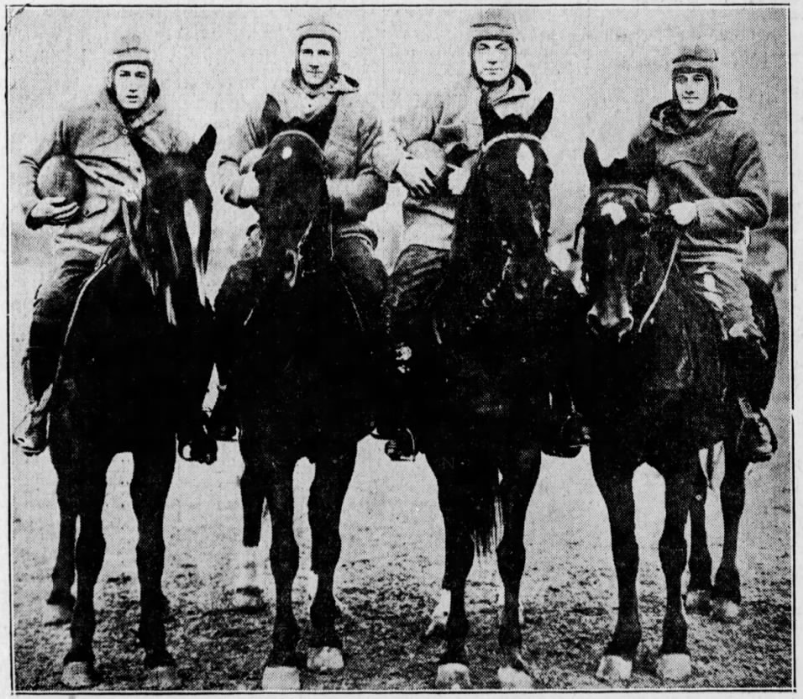

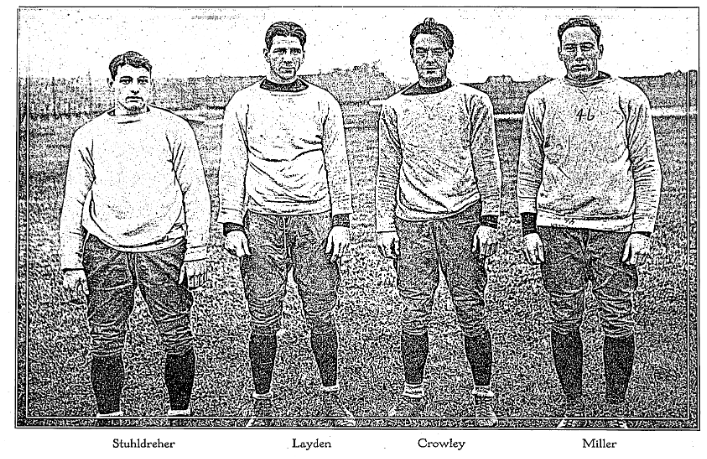

The New York Times reported that the 60,000 person crowd that gathered at the New York City Polo Grounds was the largest ever in that city. The reporter raved about “Knute Rockne’s Notre Dame football machine, 1924 model” and their “speed, power, and precision.” [16] He gave special notice to the backfield, referring to their “poetry of motion.” Writing for the New York Herald Tribune, reporter Grantland Rice went further in praising the backfield of Harry Stuhldreher, Don Miller, Jim Crowley, and Elmer Layden. In a passage described by Sperber as perhaps the most famous in sports history, Grantland wrote:

Outlined against a blue, gray October sky, the Four Horsemen rode again. In dramatic lore, they are known as Famine, Pestilence, Destruction and Death. These are only aliases. Their real names are Stuhldreher, Miller, Crowley, and Layden. [17]

In fact, this famous line came from Notre Dame’s own publicity machine. George Strickler, a press assistant employed by the university had just seen Rex Ingram’s new movie, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. Strickler mused that the Notre Dame backfield recalled “those ethereal figures charging through the clouds.” [18] Rice took the idea and made it his lead. The article quickly found a life of its own. The catchy lead was picked up by other newspapers and the nickname stuck. Strickler was delighted with the press coverage and determined to make the most of it. He called the university and arranged to have a photographer shoot a picture of the “horsemen” upon their return — on horseback, of course.

With more attention on them than ever before, the Fighting Irish still had most of their season ahead of them. When they faced the Princeton Tigers on October 25, 1924, it seemed like they might not survive the increased scrutiny. Despite the previous year’s upset, Princeton was favored to win as the Tigers defensive line was much improved. When the game kicked off before 45,000 spectators, Coach Rockne again started his substitutes. At one point in the first quarter, Princeton nearly scored, with the second-string Irish stopping the Tigers at the three-yard line. The game quickly shifted in Notre Dame’s favor when the starters entered the fray. The Four Horseman again stole the show. The New York Times reported that “the darting thrusts of Notre Dame’s lightning backfield were more than Princeton could handle today.” Left half-back James Crowley scored two touchdowns for a 12-0 Notre Dame win. [19] But all was not smooth sailing for the Irish, as quarterback Harry Stuhldreher, who was responsible for the most yards gained that game, was injured. Notre Dame was down one horseman as they returned to South Bend.

On November 1 Notre Dame faced Georgia Tech for their homecoming game at Cartier Field. By now, Coach Rockne’s method of tiring out the opposing team while holding back his best players had been published in newspapers across the country. Perhaps recognizing that their best chance at scoring was against the second string starters in the first quarter, the Georgia Tech Golden Tornado team came out strong. The Chicago Tribune reported:

Georgia Tech took advantage of the Notre Dame seconds early in the first period, and [full back Douglas] Wycoff promptly ran through the bewildered Rockmen for 40 yards, placing the ball on Notre Dame’s 35 yard line. [20]

Georgia Tech “place-kicked” for three points and the second-string Irish struggled through the first quarter. While Rockne’s strategy was no longer a surprise, it was still effective. When the varsity Irish started the second quarter they were unstoppable, even without the injured Stuhldreher. The other three horsemen led the team to a 34-3 victory with several substitutes also making important contributions. [21] Next, the Irish were ready to take on their first Big Ten team.

Notre Dame faced the Wisconsin University Badgers on November 8th before a crowd of 40,000. While it was an away game for the Irish, it didn’t feel like it to the players. The game was the main attraction for an annual student trip, and so the blue and gold section in the stands was full. The Notre Dame marching band came as well and marched out onto the field playing fight songs. The first quarter saw Rockne’s second-string starters equally matched with the starting Badgers and the quarter ended 3-3, but the tide quickly turned in favor of Notre Dame. The Notre Dame Official 1924 Football Review reported on the start of the second quarter:

Then came the call, and the entire first team burst onto the field while the Notre Dame stands went into an uproar. Then the fun began. [22]

With all four horsemen in the game, the Badgers didn’t stand a chance. “They simply galloped over the foe,” the Chicago Tribune reported. [23] The score was 17-3 at the half and 31-3 within the first ten minutes of the third quarter. Rockne called in his varsity players and gave some third stringers and rookies the chance to play. The Tribune joked that “no one in the press stand could call them by name” and that Coach Rockne probably could not either. [24] In the final quarter, Rockne put back in his starting “shock troops” who brought the final score to 38-3 for a sweeping Notre Dame win. The students in the stands threw their hats and rushed onto the field to follow their marching band, snaking across the gridiron while singing and dancing. The Chicago Tribune spotted some “well-known Chicago men of Celtic origin out there romping with the students.” [25] Notre Dame was becoming the beloved team of people with Irish heritage across the country. Thus, it was even more important that they beat Nebraska.

The Klan had not forgotten about South Bend. On November 8, while the Fighting Irish celebrated their win over Wisconsin, 1,800 Klansmen and women “from Chicago and from a number of Indiana cities,” gathered just outside the city limits. [26] Between six and seven o’clock they paraded through the streets of South Bend, a quick clip compared to other Klan parades and events. There was little reaction to their presence and the South Bend Tribune reported that “few people were on the streets.” [27] It’s not clear why there was no response from students. Perhaps they simply didn’t have advance notice of the parade, and when the event happened quickly, they didn’t have time to form a response. Maybe they simply refused to be baited into further confrontations. Either way, the Klan had surely succeeded in reminding the Irish Catholic students that the threat of violence still loomed.

The Fiery Cross claimed that the Klan held yet another South Bend parade on November 11, just days after the quiet, uneventful rally of a few days earlier. The newspaper claimed that thirty-five thousand members from across the Midwest gathered and paraded through the city, purportedly “one of the biggest Ku Klux Klan demonstrations ever held in this section of the country.” [28] The Fiery Cross again claimed that the Klan had the cooperation of the mayor and the police chief. No other newspaper reported on the event. The Klan newspaper’s claims are dubious. A crowd this large would surely have drawn at least passing comment from the South Bend Tribune. It seems more likely that this was hype generated by their propaganda machine after the turnout for the rally on the 8th was reported by the South Bend Tribune to have been small. Whether the Klan gathered that day or whether this was just more propaganda, Notre Dame students and officials certainly felt the continued threat. For now, however, the Notre Dame players and their supporters had their eye on a different kind of opponent, albeit one with anti-Catholic prejudices of their own.

The last time they faced the Cornhuskers, the 1923 Fighting Irish team encountered prejudice and xenophobic epithets from Nebraska fans. The university was also still facing public backlash and disapproval from the violent confrontation with the Klan the previous May, as well as the Klan’s ongoing propaganda campaign. In an attempt to remedy their school’s reputation, the 1924 Notre Dame football players had handled themselves with dignity throughout the season, serving as examples of upstanding Catholic American citizens and scholars. But they still needed to beat Nebraska for two reasons. One, the symbolic victory of the hardworking and stoic Irish Catholic school over a team with anti-Catholic fans would be significant to their Irish Catholic supporters in an era dominated by the Klan. Two, to revenge their only loss of the previous season and make 1924 an undefeated perfect season would give them the public platform they needed to further improve the reputation of Notre Dame.

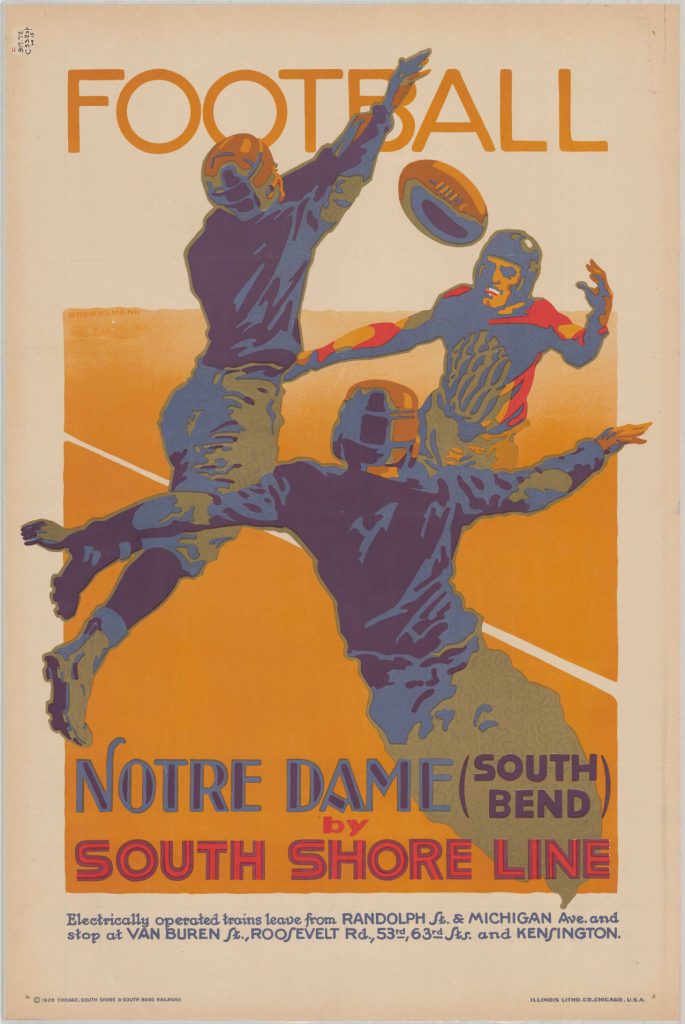

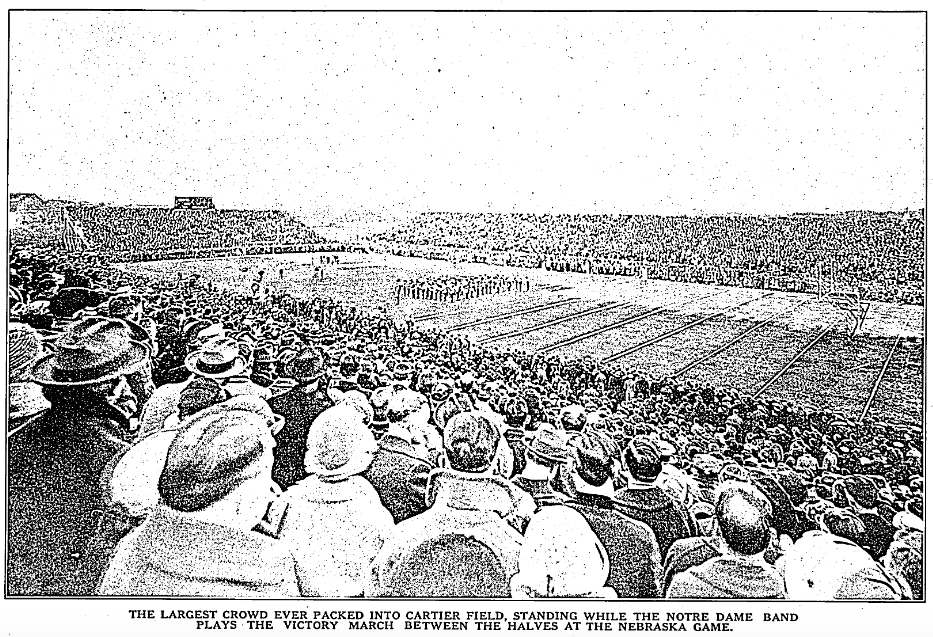

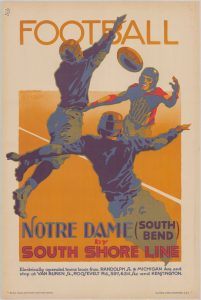

The Notre Dame Fighting Irish faced the Nebraska Cornhuskers November 15, 1924 at home in South Bend. Notre Dame supporters packed the stands at the recently enlarged Cartier Field while overflow fans stood on the sidelines or even sat on the fences. The local newspaper estimated the crowd at 26,000 people, the largest to date. [29] Recognizing the increasing popularity of the Notre Dame team to those in the wider area, the WGN radio station in Chicago delivered a live broadcast of the game. [30] Likewise, the South Shore interurban line, which ran between South Bend and Chicago, created large color posters of Notre Dame football players in action to advertise their service. [31]

Football fans had a beautiful day for the game, which was “easily the headliner” of Midwestern match ups that week, according to the Lincoln Star. [32] The newspaper reported: “A glorious November sun was shining through golden haze and the tang of frost was in the air.” [33] Photographs from game day show supporters well-bundled in hats and coats.

This game had been the focus of the entire season for Notre Dame. The players’ had written slogans on their dressing room lockers such as: “Get the Cornhuskers” and “Remember the last two defeats” (losses in 1922 and 1923). [34] A Lincoln newspaper complained that “Rockne has pointed his team for Nebraska and doesn’t mind telling the world about it.” One reporter stated simply: “They hope to taste revenge.” [35]

The players took the field at 2:00 and it was clear almost immediately that Rockne’s shock troops would not be able to handle the Cornhuskers. The second stringers fumbled early, got penalized for being offsides, and Nebraska pushed through to the four-yard line. Not taking any chances, Coach Rockne swapped the troops for his first-stringers. But it was Nebraska’s ball and they were able to drive through the remaining yards for a touchdown. [36] That touchdown would be Nebraska’s last of the game.

The Irish thoroughly outplayed the Cornhuskers with much of the credit going to the Four Horsemen. The South Bend Tribune reported:

First it was Miller circling around the ends for notable gains, then it was Crowley, and then there was Layden splitting the line with the speed and momentum of a cannon ball. Then to top it off there was Stuhldreher to carry the ball or to toss the pigskin with deadly accuracy into the hands of his waiting backs. They were all there, they were all stars and together they make Notre Dame the greatest eleven in football history. [37]

In the end, Notre Dame beat Nebraska 34-6, but even that score did not reflect how well the Irish played. The Tribune reported, “Twenty-three first downs for Notre Dame gave the fans some idea of the complete swamping the western players received.” [38] The most significant aspect of the win for the Fighting Irish though was symbolic. They had finally overcome a rival who had not only ruined their otherwise perfect 1923 season, but had insulted them with anti-Catholic, anti-Irish slurs as well. The Tribune summarized the feeling that day for the victors:

There may be games with more sensational playing, with more artistic foot-ball handling, but none, past or future, will ever appeal to the heart of Notre Dame men as this game which witnessed Rockne erasing the memory of two years defeat, but trouncing the huge Cornhusker squad soundly, without apology. [39]

Rockne reveled in both the football win and the symbolic victory of besting a team whose fans had personally humiliated his players. Rockne said, “Nebraska, as usual, was the dirtiest team we played, and after the game, a few of their players even called me a few choice epithets.” [40] The next game would have symbolic undertones as well. Catholic Notre Dame would face Methodist Northwestern.

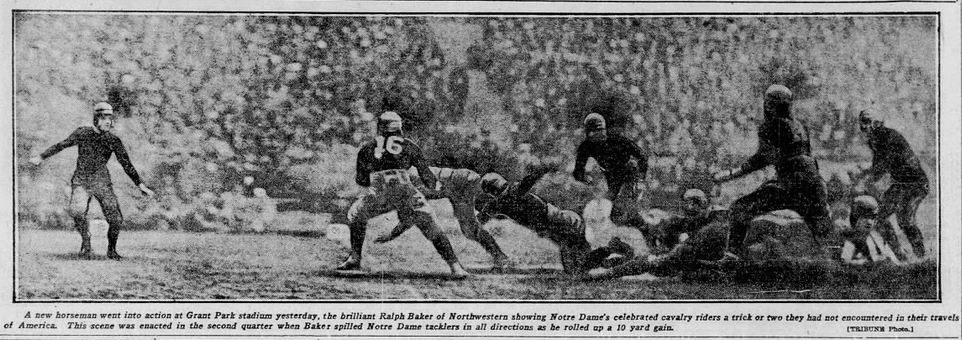

For the November 22 Notre Dame – Northwestern match up, Rockne manged to move the game from Northwestern’s hometown of Evanston, Illinois, to Chicago. As the Irish middle class grew in Chicago, so did support for Notre Dame football in the city. Over 45,000 people bought tickets, the majority of them Notre Dame fans. [41] The game played that day at Grant Park (soon to be called Soldier Field) was the most difficult of the season. Northwestern held the lines against the Horsemen for much of the game and their halfback, All-American Ralph “Moon” Baker “threatened for a time to act as presiding host at an Irish wake,” according to one Chicago reporter. [42] After Northwestern almost immediately scored three points, fans began chanting for the Horsemen, and Rockne put in his first stringers. But Northwestern scored another three, giving them six points and leaving Notre Dame scoreless. The Irish rallied soon after and began to arduously shift the game in their favor. Stuhldreher ran for a touchdown in the second with Crowley’s field goal giving the Irish a one point advantage by the half. After a scoreless third quarter, Layden ran 45 yards for a touchdown in the fourth. Notre Dame won 13-6 against a tough Northwestern team. [43]

Notre Dame played their last game of the regular season against Carnegie Tech on November 29, 1924. Tech played well, scoring three touchdowns – two against the shock troops but one against the regulars, minus one Horseman (Bernard Livergood and William Cerney filled in for Elmer Layden who was injured). Even so, Notre Dame dominated the contest with their passing game drawing note in the press. The Fighting Irish beat Carnegie Tech 40-19, and closed the season undefeated in nine games. [44] This perfect record was everything the university administration had hoped for in order to engage their publicity machine and improve the school’s marred reputation. A trip to the Rose Bowl gave them the opportunity to set their plan into action. On New Year’s Day 1925, Notre Dame would play the Stanford University Indians, a game that’s long remembered in the history of this classic Fighting Irish Team. More significantly, the several week tour by rail of the Midwest and West masterminded by Father O’Hara forever repaired the university’s reputation. According to Notre Dame historian Robert E. Burns:

O’Hara saw the Rose Bowl invitation as an almost providential opportunity to counter the extremely negative Klan-inspired image of Notre Dame . . . [and] might well turn out to be the most successful advertising campaign for the spiritual ideals and practices of American Catholicism yet undertaken in this century. [45]

The Klan continued their propaganda campaign into December, through the weeks leading up to the Rose Bowl. As they prepared for the big game, the Fighting Irish faced anti-Catholic vitriol and hatred that the Klan had helped to make socially acceptable. Nonetheless, the Notre Dame football team would establish themselves not only as the greatest players in the country, but also as patriotic Americans, many the sons of Irish immigrants, and as proud Catholics.

See the conclusion of this series, Integrity on the Gridiron Part Three, to learn about the Notre Dame publicity campaign that crushed the Klan in South Bend.

Notes

*The University of Notre Dame did not officially accept the name “Fighting Irish” for their athletic teams until 1925, but newspapers had been using it for quite a while beforehand.

[1] Robert E. Burns, Being Catholic, Being American: The Notre Dame Story, 1842-1934 (University of Notre Dame Press, 1999) 347-48.

[2] Murray Sperber, Shake Down the Thunder: The Creation of Notre Dame Football (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1993, reprint, 2003), 157-158.

[3] “Where the Klan Fails,” New York Times, November 1, 1923, accessed timesmachine.nytimes.com.

[4] Sperber, 157-58.

[5] Burns, 348.

[6] Harry McGuire and Jack Scallan, eds., Official 1924 Football Review, University of Notre Dame, 24, accessed Notre Dame Archives.

[7] Ibid., 17.

[8] “Notre Dame Too Husky; Lombard Loses by 40 to 0,” Chicago Sunday Tribune, October 4, 1924, reprinted in Official 1924 Football Review, accessed Notre Dame Archives.

[9] Notre Dame Defeats Wabash, 34-0,” South Bend Tribune, October 12, 1924, 1, accessed Newspapers.com.

[10] Ibid.

[11] “Expect 200,000 at Gathering: South Bend To Be Host to Klansmen,” Fiery Cross, October 10, 1924, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[12] Burns, 342-44.

[13] “Prepare for Large Gathering: South Bend Ready for Many Visitors from Four States,” Fiery Cross, October 17, 1924, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Sperber, 164.

[16] “Notre Dame Eleven Defeats Army, 13-7; 60,000 Attend Game,” New York Times, October 19, 1924, 118, accessed TimesMachine.

[17] Sperber, 178-79.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Notre Dame Sweeps Princeton to Defeat,” New York Times, October 26, 1924, 116, accessed TimesMachine.

[20] “Notre Dame Is 34-3 Victor Over Golden Tornado,” Chicago Tribune, November 1, 1924 reprinted in Official 1924 Football Review, accessed Notre Dame Archives.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Official 1924 Football Review, 36, accessed Notre Dame Archives.

[23] James Crusinberry, Chicago Tribune, November 8, 1924, reprinted in Official 1924 Football Review, accessed Notre Dame Archives.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] “Klansmen in Parade,” South Bend Tribune, November 9, 1924, 3, accessed Newspapers.com.

[27] Ibid.

[28] “No Violence of Any Sort Mars Parade,” Fiery Cross, November 14, 1924, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[29] Kenneth S. Conn, “Notre Dame Soars Over Corn-Fed Nebraska,” South Bend Tribune, reprinted in Official 1924 Football Review, 39, accessed Notre Dame Archives.

[30] “N. Dame Stakes National Title on Tilt Today,” Chicago Tribune, November 15, 1924, 17, Newspapers.com.

[31] “Football: Notre Dame (South Bend) by South Shore Line,” 1926, broadside, Indiana State Library Broadside Collection, accessed ISL Digital Collections.

[32] Edward C. Derr, “Nebraska – Notre Dame Classic Dominates Interest,” Lincoln Journal Star, November 14, 1924, 16, Newspapers.com.

[33] Cy Sherman, “Nebraska Battles Notre Dame: Cornhuskers Clash with Irish Eleven,” Lincoln Star, November 15, 1924, 1, Newspapers.com.

[34] Jim Lefebvre, Loyal Sons: The Story of The Four Horsemen and Notre Dame Football’s 1924 Champions, excerpt reprinted in “This Day in History: Irish Topple A Nemesis,” Department of Athletics, University of Notre Dame, https://125.nd.edu/moments/this-day-in-history-irish-topple-a-nemesis/.

[35] Edward C. Derr, “Nebraska – Notre Dame Classic Dominates Interest,” Lincoln Journal Star, November 14, 1924, 16, Newspapers.com.

[36] Cy Sherman, “Nebraska Battles Notre Dame: Cornhuskers Clash with Irish Eleven,” Lincoln Star, November 15, 1924, 1, Newspapers.com.

[37] Kenneth S. Conn, “Notre Dame Soars Over Corn-Fed Nebraska,” South Bend Tribune, reprinted in Official 1924 Football Review, 39, accessed Notre Dame Archives.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Sperber, 167.

[41] Ibid., 167-68.

[42] Jimmy Corcoran, “Notre Dame is Forced to the Limit,” newspaper not cited, November 22, 1924, reprinted in Official 1924 Football Review, 41, accessed Notre Dame Archives.

[43] Ibid.; “Game By Quarters,” South Bend Tribune, November 23, 1924, 14, Newspapers.com.

[44] Warren W. Brown, “Notre Dame Gallops Over Carnegie Tech,” Chicago Herald Examiner, reprinted in Official 1924 Football Review, 43, accessed Notre Dame Archives.

[45] Burns, 369.