Part one, covering Bilby’s early life and years working for the US Coast and Geodetic Survey, can be read here.

———————————————————-

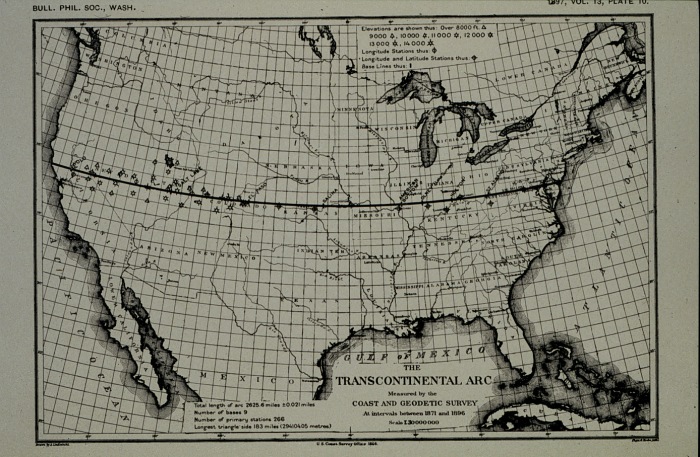

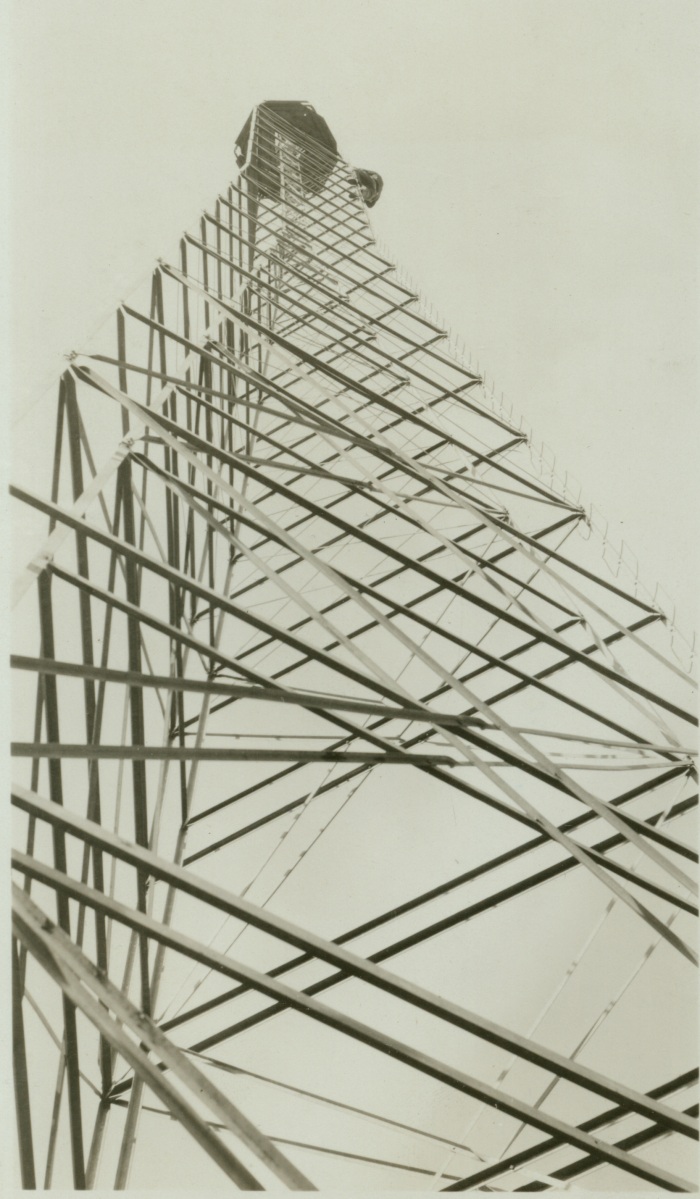

Jasper Sherman Bilby’s time in the US Coast and Geodetic Survey (US C&GS) is best remembered for his invention, the Bilby Steel Tower. The tower revolutionized the Survey’s procedures, costs, and efficiency. As described by historian John Noble Wilford, the Bilby Tower was used for horizontal-control surveys (measuring latitude and longitude) and allowed surveyors to see over hills, trees, and other impediments to make their measurements more accurate.

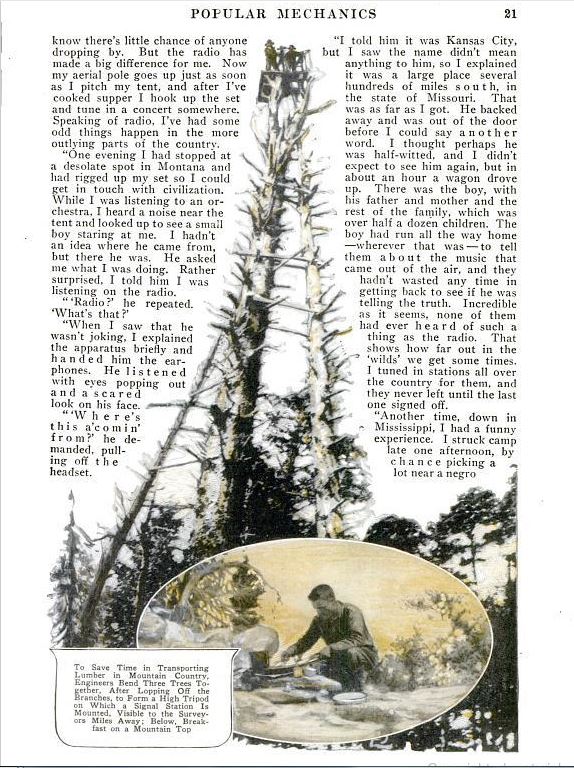

In his manual, Bilby Steel Tower for Triangulation, Bilby detailed this problem of visibility:

In many regions it is not possible to select stations for a scheme of triangulation and have the stations intervisible from the ground, as trees, buildings, and other objects obstruct the line of vision between adjacent points. On geodetic surveys, covering wide expanses of territory, the curvature of the earth must also be taken into account. Towers are, therefore, necessary to elevate above intervening obstructions the observer and his instrument at one station and the signal lamp or object on which he makes his observations at the distant station.

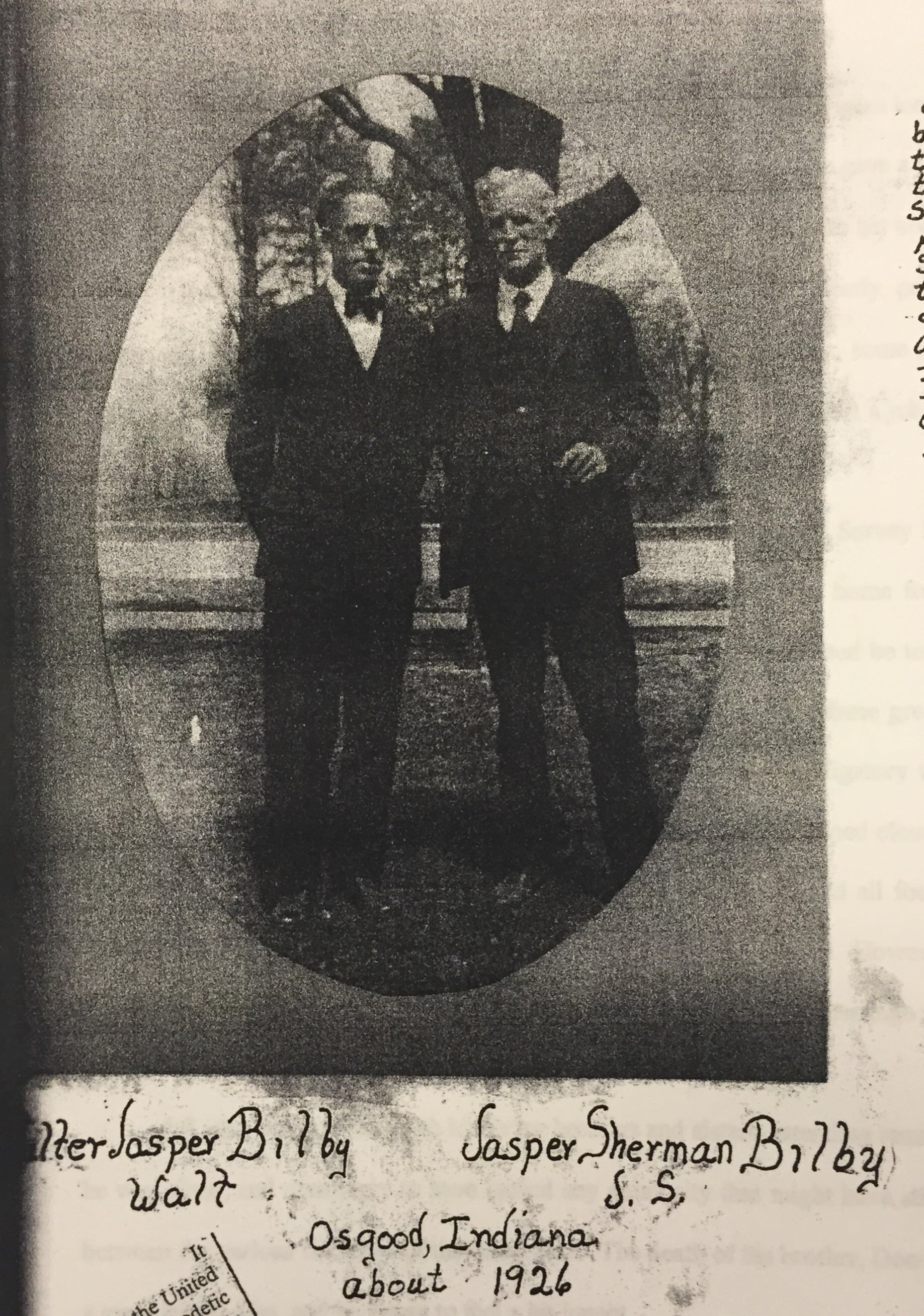

According to US C&GS documents on his field assignments, Bilby began his designs on the tower as early as December 1926. He then took his early design plans to the Aeromotor Factory in Chicago to make a prototype. Once the prototype proved successful, twelve complete towers were manufactured by the same company and were first tested on assignment in Albert Lee, Minnesota with positive results.

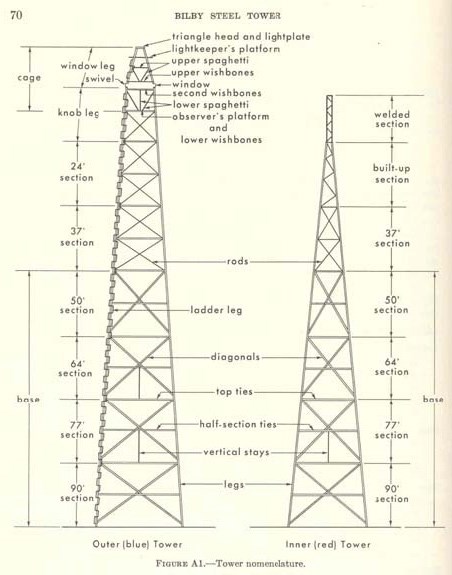

In terms of design, the Bilby Tower was actually comprised of two independent towers. An inner tower carried the intricate instruments for survey calculations and the outer tower supported the surveyors who made the measurements. These towers never connected, so that the vibrations of either one did not disturb the survey calculations. In 1927, it was named the “Bilby Steel Tower” by Colonel Lester E. Jones, then director of the US C&GS.

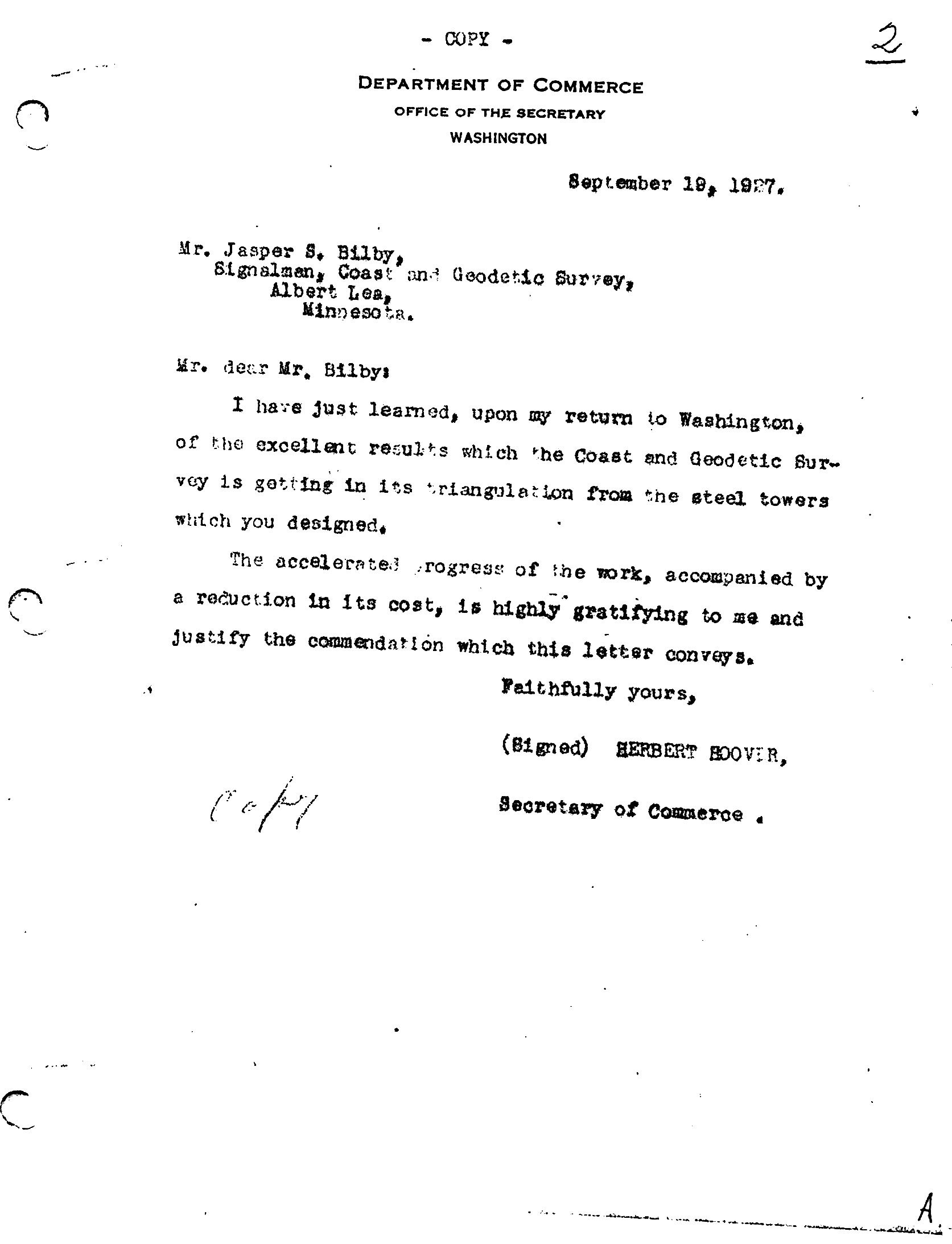

In a 1927 commendation letter, Secretary of Commerce (and future President) Herbert Hoover commended Bilby’s invention for its cost and time efficiency and cited the surveyor’s service as essential to the United States government.

I have just learned, upon my return to Washington, of the excellent results which the Coast and Geodetic Survey is getting in its triangulation from the steel towers which you designed.

The accelerated progress of the work, accompanied by a reduction in its cost, is highly gratifying to me and justify the commendation which this letter conveys.

However, Hoover’s letter was not the only special commendations he received while in the US C&GS. He earned financial promotions through 1915- 1916 and in 1930, the position of “Chief Signalman” was created for him. Understanding Bilby’s work as essential to the US C&GS, President Hoover used an executive order in 1932 to waive the mandatory federal retirement age.

Within the first ten years of use, the Bilby Steel Tower saved the federal government $3,072,000, according to the itemized cost listing of both wooden and steel towers from 1927-1937 by the US C&GS field assignment reports. The 1928 US C&GS annual report explained how the implementation of Bilby Towers cut unit costs down by nearly half, much more than the projected 25-35% savings. It also increased their surveying progress to over “150 miles per month.”

Within a few years of its invention, the Bilby Steel Tower was used in nations such as France, Australia, Belgium, and Denmark. In particular, Major M. Hotine, Royal Engineer of the Ordinance Survey Office in Southampton, England, wrote of his satisfaction with the Bilby Steel Tower in the December 1938 issue of the US C&GS Field Engineers Bulletin:

We have just completed among other work this season, the primary observation for our new triangulation in the Eastern Counties of England. The country here is so flat and enclosed that we had to use Bilby Steel Towers at 34 of the main Stations [sic], to say nothing of several secondary stations surrounding such Steel Tower States, we thought it would be advisable to observe at the same time as the primary work. You may be interested to know that these admirable Steel Towers were entirely satisfactory; and that we were very deeply impressed with the conception, design, and construction of these Towers.

Along his invention, he wrote several government manuals on the theory and practice of geodetic surveying. His most famous and influential work was the manual on his invention, the Bilby Steel Tower. Bilby Steel Tower for Triangulation (1929) covered every aspect of his invention, from concept and construction to its usage and transport. It stayed in publication through two editions. Other manuals include Precise Traverse and Triangulation in Indiana (1922), Reconnaissance and Signal Building (1923), and Signal Building (1943).

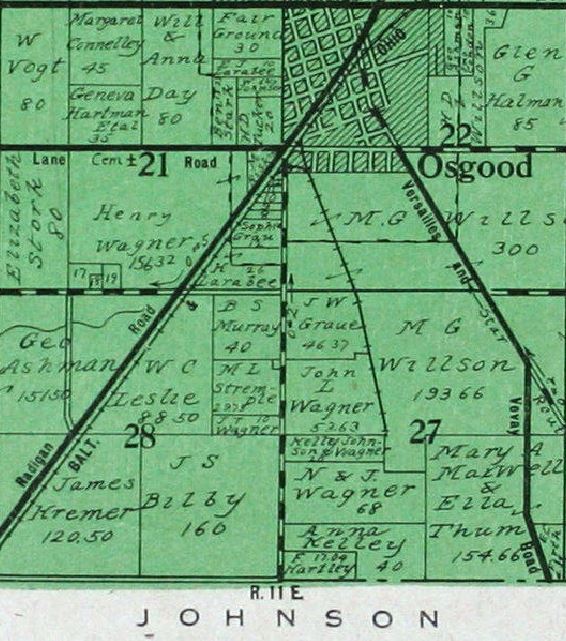

Bilby retired from the US C&GS in 1937. His final assignment was at a triangulation station in Hunt City, Jasper County, Illinois, completing his 53 year career exactly where it began on the 39th parallel. His 1927 manual for the Bilby Tower was revised for surveyors in 1940 and his work continued to influence the trade well into the 1980s. The last Bilby Tower was erected in 1984, in Connecticut. A complete survey tower, originally constructed on an island south of New Orleans, Louisiana called Couba in 1972, was restored and moved to the town park in Bilby’s hometown of Osgood, Ripley County, Indiana in 2014.

Bilby died on July 18, 1949 in Batesville, Indiana. He was buried in Washington Park Cemetery in Indianapolis. His long career and advancements in geodetic surveying technology, particularly on the 39th parallel, ensured the completion and accuracy of the National Spatial Reference System (NSRP), a first-order triangulation network of the United States.

The NSRP, according to the National Geodetic Survey, is a “consistent coordinate system that defines latitude, longitude, height, scale, gravity, and orientation throughout the United States.” This system’s continued use ensures accurate information for the United State’s Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS), known domestically as the Global Positioning System (GPS).

Jasper Sherman Bilby’s innovation and inventiveness left an indelible mark on surveying in the United States and the world. His Bilby Steel Tower, and the knowledge it advanced, revolutionized mapmaking for generations.

In short, Bilby helped us map the earth.