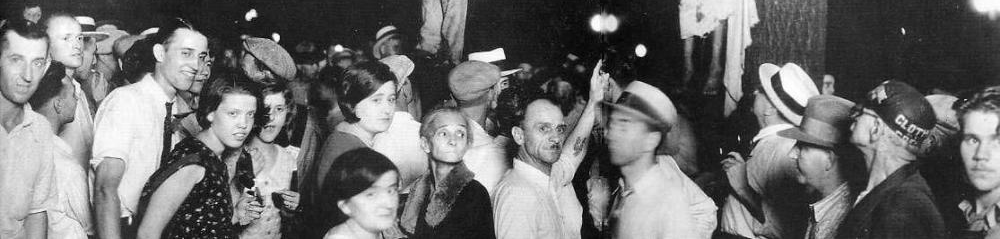

Lawrence Beitler’s photograph of young Black men swinging from a tree as a white crowd looks on in satisfaction lingers in our collective memory. In fact, the local photographer’s snapshot inspired Abel Meeropol’s poem “Strange Fruit,” which continues to resonate with activists, as well as artists like Nina Simone and John Legend. But what happened after the bodies of Tom Shipp and Abe Smith were removed from the tree hours later—when tensions remained so high? And can anything be learned by examining the immediate aftermath of the 1930 Marion lynching?

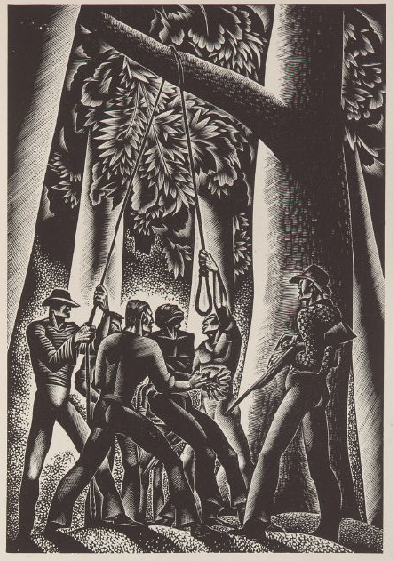

On August 7, African American teenagers Shipp, Smith, and James Cameron were held in the Marion jail for the murder of Claude Deeter and rape of Mary Ball. Before the young men could stand trial, a mob comprised of white residents tore the young men from their cells, brutally beat and mutilated them before hanging Shipp and Smith from a tree on the courthouse lawn. Cameron narrowly escaped the fate of his friends. The mob intended to send a message to the African American community that they were at the mercy of white residents, despite the courageous efforts of Marion NAACP leader Katherine “Flossie” Bailey to prevent the tragedy. Read more about her efforts here.

After the lynching, the crowd lingered to prevent the coroner from removing the bodies, insistent that the message be received. This was the same crowd that had left the jail “ravaged,” with “gaping holes in the walls” and the “twisted remains of broken locks.” The Indianapolis Recorder, an African American newspaper, reported that after Shipp and Smith had been robbed of their lives, the perpetrators drove past the victims’ houses, shouting at their parents, “‘we have lynched your sons, now cry your eyes out.'”[1]

Reportedly by midnight, an “indignation meeting” formed in Johnstown, the Marion neighborhood where African Americans lived. Hundreds of shaken Black residents listened to speeches condemning the sheriff’s unwillingness to order officers to shoot at the mob. Munster newspaper The Times reported on the August 9 gathering, noting that although police dispersed the gatherers, “Negro leaders told officials trouble was brewing and might flare up at any moment.” Out of fear of escalating violence, about 200 Black residents fled Marion for Weaver, a historic Black community in Grant County.

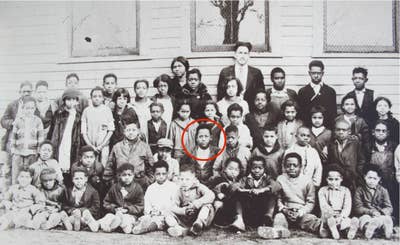

Amid the maelstrom of fury and fear, Shipp’s and Smith’s bodies were taken to Shaffer Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Muncie because Marion lacked a black mortician. Before the Black community could grieve, reports spread that a white mob was traveling to Muncie to light the victims’ bodies on fire. According to historian Hurley C. Goodall’s A Time of Terror: The Lynching of Two Young Black Men in Marion, Indiana on August 7, 1930, Muncie’s African American community was determined to protect the victims’ bodies from further violence, and “for the first time they armed and organized themselves using Shaffer Chapel A.M.E. Church as their headquarters and command post to ward off any mob.” In an oral history interview for the Black Muncie History Project, Thomas Wesley Hall, an African American resident of Muncie at the time of the lynching, confirmed that Muncie citizens gathered to protect the young men’s bodies from further desecration.

After the mortician embalmed Shipp and Smith, National Guardsmen escorted the bodies back to Marion, where “two grief-stricken mothers . . . bemoaned the unjust fate of their boys.”[2] Friends gathered at the victims’ homes to hear final rites and tried to console their mothers, able only to mumble “‘it’s too bad, it’s too bad.'”[3] A Black resident later described Shipp, an employee at the Malleable foundry, as a “good boy who ‘helped his mother.'”* The Guardsmen “paced back and forth in front of these humble homes to defy with gunfire, if necessary the sworn threat of mob leaders, to burn their bodies.”[4] A “dead line” had been set, around which no white person was to pass. Although they did not attempt to set fire, white people drove past the line to “satisfy their morbid fancies” and revel that a “‘job had been done well.'”[5]

Smith was buried in Weaver, the settlement where African Americans had fled following the lynching. The Recorder marveled poetically, “Strangely enough, Weaver was a station on the ‘underground railroad’ by which slaves, who escaped the South, found a new freedom in the North.”[6] Shipp was buried in a small cemetery in Marion. A combination of the National Guard and Muncie’s Black community allowed Thomas Shipp and Abe Smith to be peacefully laid to rest. In fact, the Recorder reported “Citizens here, both white and Colored are loud in their praise of the splendid conduct of the members of the National Guard which made it unnecessary for anyone to turn his back upon his home.”[7]

Once the young men were laid to rest, the Black community was left to cope with unfathomable grief. How did the victims’ friends and family process their trauma and sorrow? For James Cameron, survivor of the lynching, it meant confronting local racism through threat of lawsuits and, later, by educating the nation about racial injustice by founding America’s Black Holocaust Museum in Milwaukee.

According to Syreeta McFadden’s “What Do You Do After Surviving Your Own Lynching?,” when the white crowd stormed the jail Black prisoners tried to defend Cameron, the youngest of the three accused. Cameron recalled that the prisoners “had become too angry to remember their own fear — if they had any. But they were helpless and powerless to offer any kind of resistance to the mob. They stood with me.”[8] But they couldn’t stop Cameron from being dragged outside, where a noose was thrown around his neck. An anonymous bystander shouted that Cameron had not been involved in the crime, causing the throng to fall silent.

Cameron described the surreal moment saying, “I looked at the mob round me I thought I was in a room, a large room where a photographer had strips of film negatives hanging from the walls to dry. . . . they were simply mobsters captured on film surrounding me everywhere I looked.” He recalled:

‘Brutally faced with death, I understood, fully, what it meant to be a black person in the United States of America.’[9]

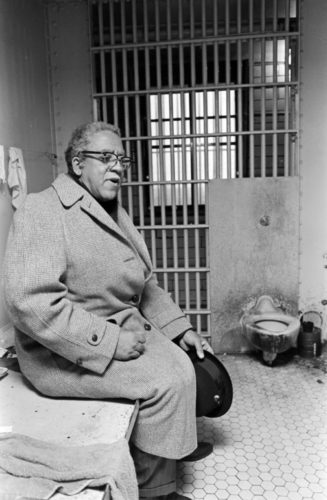

His life improbably spared, Cameron was taken to Anderson and in 1931 sentenced to twenty-one years for accessory before the fact of voluntary manslaughter. Again in a prison cell and surely reliving his trauma, Cameron began penning a book about his experiences entitled A Time of Terror: A Survivor’s Story, which he later took out a second mortgage to self-publish. Upon his 1935 release from prison, he vowed to “‘to pick up the loose threads of [his] life, weave them into something beautiful, worthwhile and God-like.’”[10]

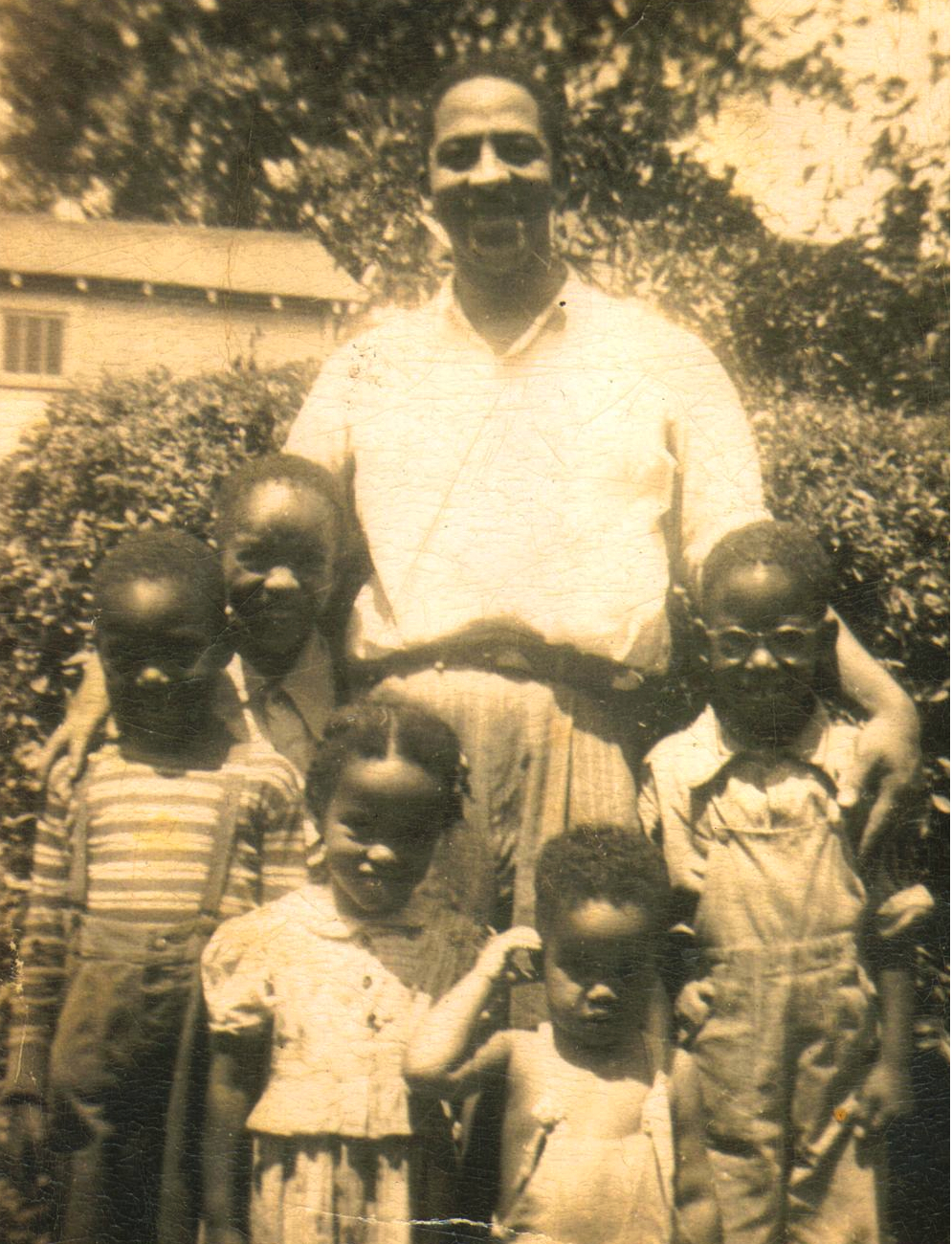

Cameron had to navigate a new life in the midst of the Great Depression. He decided to move to Detroit, where he married a nurse and had children. In order to be closer to relatives, the young family moved to Anderson in the 1940s, where Cameron worked for Delco Remy and opened small businesses. Ironically, while Anderson was segregated, the trauma he endured shielded his family from discrimination. According to McFadden, the family went to a local theater, where a white manager intervened when a colleague tried to force the family into balcony seating, stating “‘Those are the Camerons . . . Leave them alone.'” Despite a degree of deference shown to him, Cameron was determined to stamp out Jim Crowism and challenged the theater’s policies, which integrated rather than face litigation.

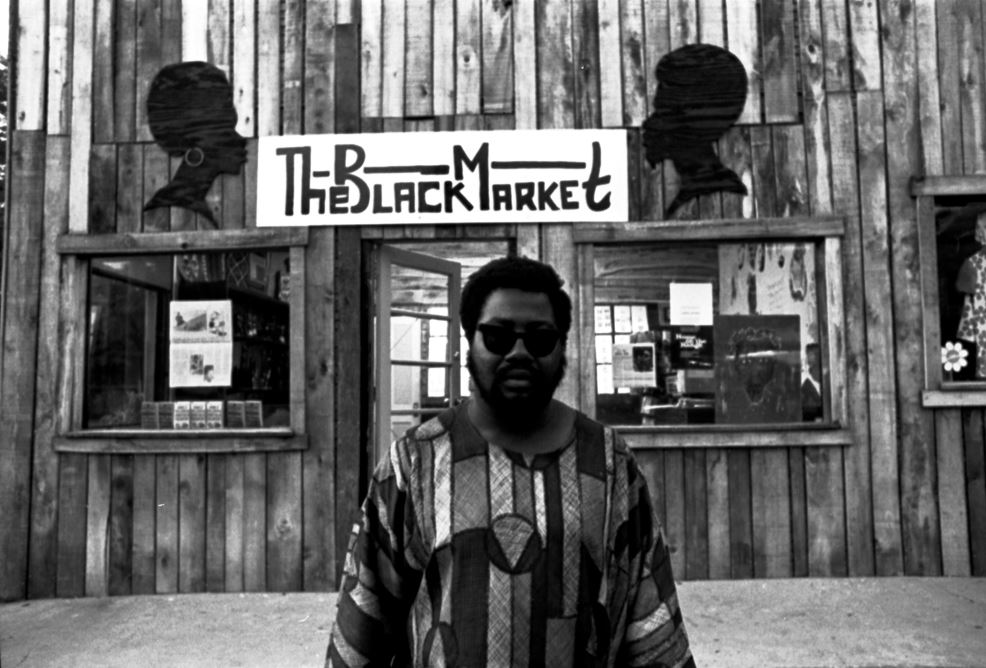

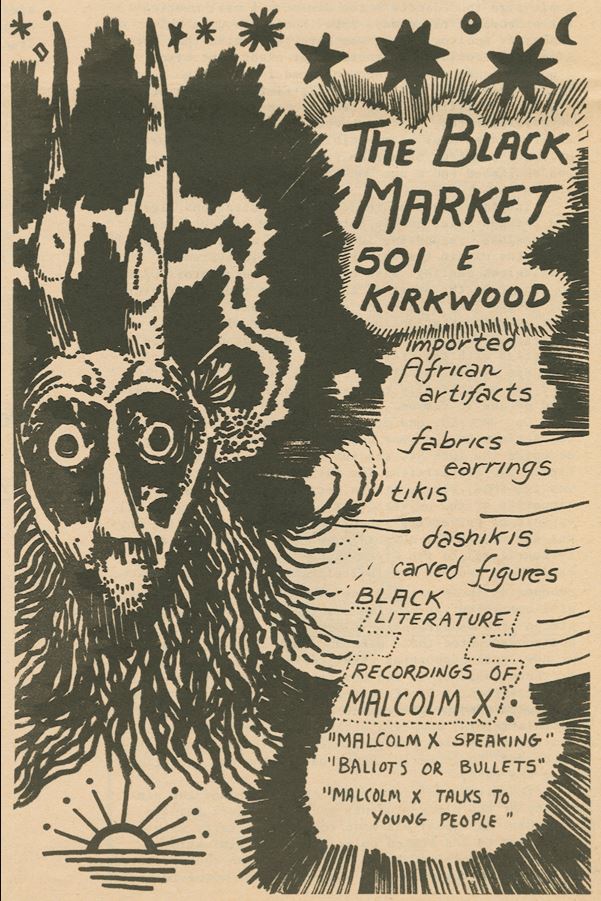

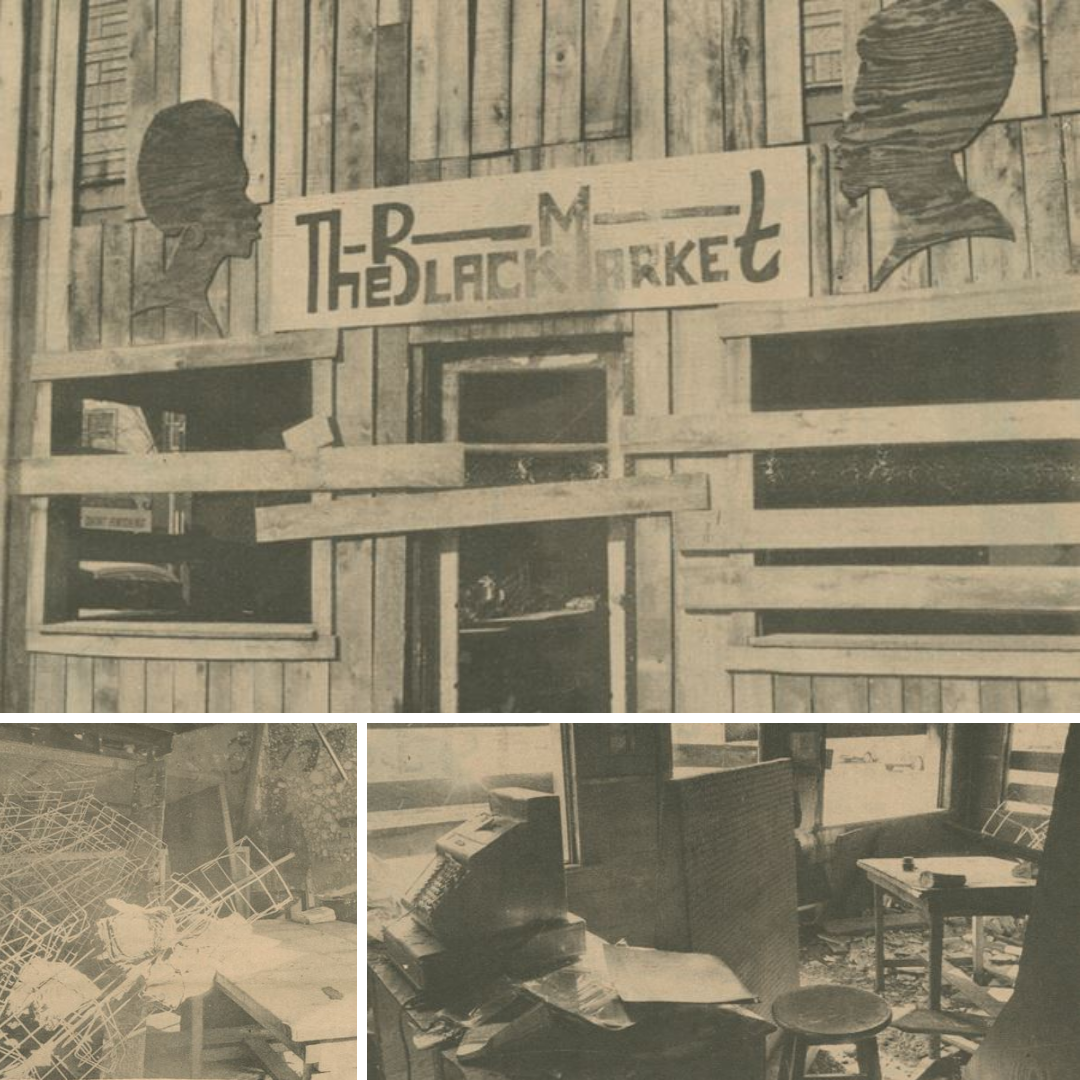

In gratitude for his life being spared, Cameron worked to eliminate prejudice against Black Hoosiers. He founded four Indiana NAACP branches and investigated civil rights violations as the state director of civil liberties.[11] This work led to threats from white residents, which he endured before moving to Milwaukee in 1950. A student of history, Cameron poured himself into learning about African Americans’ past, undertaking research trips to the Library of Congress. After a trip to Yad Vashem, a Holocaust remembrance center in Jerusalem, he connected the atrocities of the Holocaust with those perpetrated against African slaves and their ancestors in America. The revelation inspired him to establish a museum that would “‘show what happened to us black folks and the freedom-loving white people who’ve been trying to help us.’”[12]

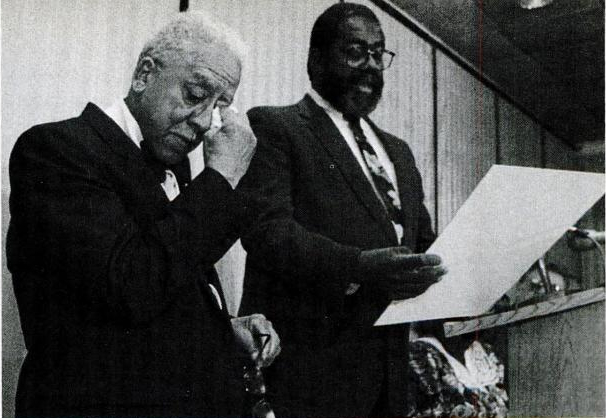

Cameron opened America’s Black Holocaust Museum (ABHM) in 1988 to “commemorate and reconcile America’s dark history.” As visitors took in an enlarged copy of the photograph of Shipp and Smith, Cameron informed them that a third man was nearly lynched that night. That man would then describe his experience, channeling his trauma into education.

In 1993, Indiana Governor Evan Bayh formally pardoned Cameron for his conviction. In fact, according to the Indianapolis Recorder, Mary Ball’s relatives stated that Shipp and Smith were not the perpetrators of either crime. Claude Deeter is said to have confirmed this at hospital before he died. Cameron passed away in 2006, leaving behind a trove of published works, several of which McFadden noted “protested many of the same issues being challenged today by the Black Lives Matter movement.” This included his “Police Community Relations Among Blacks in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.”[13] Cameron wrote that law enforcement officials “have been enemies of us black people since in [sic] their organization in the early 19th Century.”

That being said, he added:

They can do nothing to alarm or silence me beyond murdering me. Even at that, they may rest assured that I protest it — even in the grave. I have been initiated since my time of terror at the age of 16. I am 72 years old now and destined, like all other nonwhites, to experience a time of terror to the grave.[14]

Like many modern Black victims of police brutality, McFadden notes, the lives of lynching victims are often overshadowed by their deaths. ABHM strives to restore victims’ agency and give visitors a sense of who they were before their lives were taken from them. The Great Recession forced the museum to shutter its doors in 2008, and it became a virtual museum, which focused on remembrance, resistance, redemption, and reconciliation. An anonymous donation in 2017 allowed the museum to break ground at a new location, which will re-open once the Coronavirus pandemic subsides.

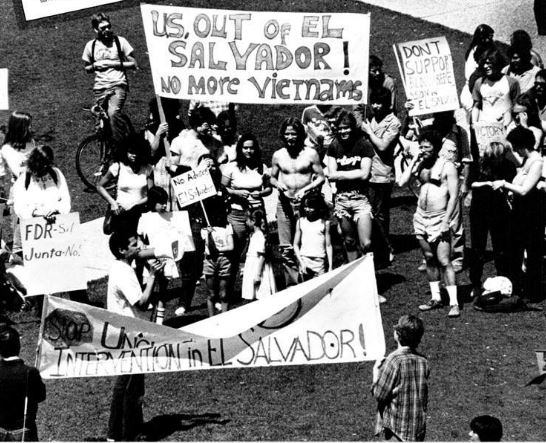

NAACP leader Flossie Bailey, who had tried desperately to stop the lynching and bring the perpetrators to justice despite threats on her life, resolved to turn her lamentation into legislative change. In 1931, Bailey organized statewide meetings, and convinced African Americans to contact their legislators to support an anti-lynching bill introduced by House Democrats. Her legwork paid off. Governor Leslie signed the bill into law in March, which allowed for the dismissal of sheriffs whose prisoners were lynched. The law also permitted the families of lynching victims to sue for damages.

Of its enactment, the Indianapolis Recorder wrote “Indiana has automatically retrieved its high status as a safe place to live.” It added that without the law, Indiana “would be a hellish state of insecurity to our group, which is on record as the most susceptible victims of mob violence.” Although the newspaper praised Governor Leslie, it credited a “small group which stood by until the bill became a law.” In addition to legislation, the NAACP tried to effect change by placing postcards with the image of the lynching in local drugstores “as a visible example of what the colored people confront.”[20] The postcards disappeared from Terre Haute drugstores after a member of the local Republican committee member bought them up.

Using the state’s legislative victory, Bailey and her NAACP colleagues worked to pass a similar bill on a federal level. According to historian James Madison, she tried to change national lynching laws by publishing editorials, wiring President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and distributing educational materials to Kiwanis clubs. Ultimately these efforts were unsuccessful and, as of 2020, a federal anti-lynching bill has yet to be enacted. Despite this legislative defeat, Bailey fought for the rights and safety of African American citizens until her death in 1952, challenging discrimination at IU’s Robert W. Long Hospital, speaking against school segregation, and suing a Marion theater for denying Bailey and her husband admittance based on their race.

It is important to note that trauma manifests differently for everyone and not all victims are capable of transforming grief into activism. In fact, the Violence Policy Center’s “The Relationship Between Community Violence and Trauma,” report concluded:

Individuals who suffer from PTSD may manifest a dangerous combination of hyper-vigilance with an impaired ability to regulate their behavior, resulting in explosive behavior and overreactions to perceived threats. In this way, the cycle of violence becomes clear – acts of violence create behavior in individuals who then beget violent acts.

This was likely the case for James Cameron’s stepfather, Hezekiah Burden. The Indianapolis Recorder noted that in the weeks after the lynching Burden was “said to have been morose and in a threatening mood.”[15] In October 1930, under the influence of alcohol, he opened fire at his wife, Vera, and stepdaughter, Marie. He then shot two police officers, likely because they belonged to law enforcement, which had failed to protect his stepson. The Indianapolis Times reported that the “Efforts of Mrs. Burden, wife of the gunman, to aid her son [James] . . . is said to have cause[d] an argument with her husband,” before he started shooting.[16] A group of armed locals exchanged fire with Burden, ultimately injuring him, which allowed police to take him into custody. The Times noted that he was moved to Pendleton State reformatory to “avoid a possible repetition of the trouble which resulted in the lynching of two Negro youth here.”[17]

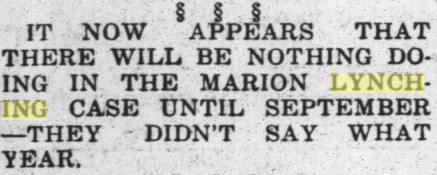

Reportedly Burden had stated his intention “to avenge ‘himself on a couple of cops,'” the judicial system having made clear there would be no justice for his stepson’s friends.[18] In December, Burden plead guilty and was sentenced to one to ten years in a state prison on three indictments related to intent to murder.[19] Neither Marion’s Sheriff Campbell nor any members of the lynching mob were sentenced for the murder of Shipp and Smith.

From the Marion lynching, we are reminded that reform stemming from tragedy often emerges slowly and in piecemeal fashion. And, like the newly-proposed police reform bills introduced in the wake of Black Lives Matter protests, it emerges because of passionate individuals who will not let up the pressure for legislative change, despite threats to their own lives. We learn that the judicial system’s refusal to hold certain perpetrators accountable begets further brutality, as in the case of Hezekiah Burden. Conversely, when groups imbued with authority like the National Guard follow through on the promise to protect and serve, tensions often de-escalate. While acts of violence and systemic suppression imprint trauma upon generations, they also awaken the revolutionary spirit. This spirit often furthers the “arc of the moral universe,” which Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. reminded listeners in a 1968 speech, is long, but “bends towards justice.”

* Journalist Cynthia Carr interviewed a Black man, who was a neighbor of Shipp’s at the time of the lynching. According to America’s Black Holocaust Museum, he told Carr “that Tommy had once told him about holding up white people, that this was justified because whites in the South had killed his uncle. The neighbor tried to dissuade Thomas from this course, pointing out that, after all, he had a good job and even a car.”

Sources:

Syreeta McFadden’s “What Do You Do After Surviving Your Own Lyching?”

Dani Pfaff’s and Jill Weiss-Simins’ historical marker review

Nicole Poletika’s “Strange Fruit: The 1930 Marion Lynching and the Woman Who Tried to Prevent It”

Notes:

[1] “State Militia Stands Guard as Funeral Rites for Lynched Marion Youths are Held,” Indianapolis Recorder, August 16, 1930, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Syreeta McFadden, “What Do You Do After Surviving Your Own Lyching?,” BuzzFeed News, June 23, 2016.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] “Marion Now Calm After Gun Battle,” Indianapolis Recorder, October 11, 1930, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[16] “Fire of Posse Member Brings Down Gunman,” The Indianapolis Times, October 6, 1930, 9, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[17] Ibid.

[18] “Marion Now Calm After Gun Battle,” Indianapolis Recorder, October 11, 1930, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

[19] “Hears Sentence as He Lays Upon Stretcher,” Logansport Pharos-Tribune, December 13, 1930, 8, accessed Newspapers.com.

[20] “Lynching Pictures Taken Off Market,” Indianapolis Recorder, September 27, 1930, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.