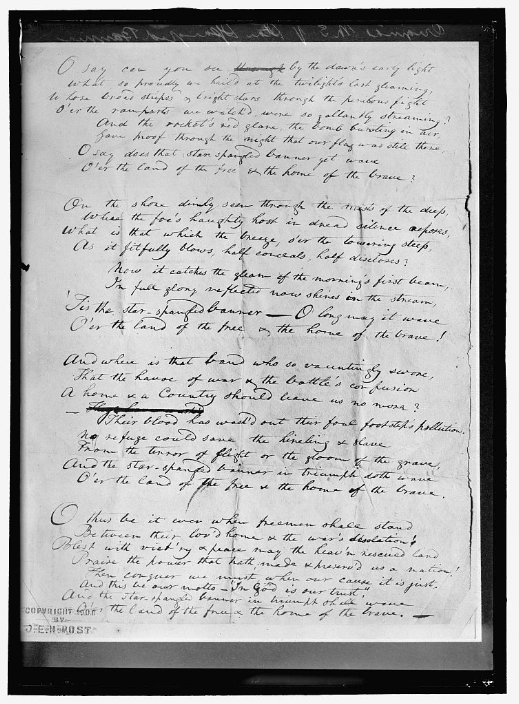

Music has long played a vital role in not only American history but also American activism. Slave spirituals were key to enduring the brutality of slave life and provided not only relief but also coded communication. Frederick Douglass wrote in his autobiography Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, “The songs of the slave represent the sorrows of his heart; and he is relieved by them, only as an aching heart is relieved by its tears.” Similarly, music has been instrumental in a variety of modern 20th century movements such as the freedom songs of the Civil Rights Movement and feminist anthems of the Women’s Movement. All movements have their anthems. But what about when it comes to our actual national anthem, “The Star Spangled Banner”?

It seems unlikely that during the War of 1812, when Francis Scott Key penned the poem that would later become our national anthem, he could have foreseen the controversy over the song that would occur centuries later. Certainly, he could not have predicted black football players taking a knee during his now musical poem prior to a professional football game, for one, because Key could not envision an America where black people lived free. While he viewed slavery as sinful (despite owning slaves himself at various points in his life), he was an anti-abolitionist who also at times upheld slaveholder rights. He personally supported the idea of black people “returning to Africa” if they were freed from slavery.

His poem, set to the tune of an English drinking song, has been rife with controversy from the beginning. Many critics thought it too militaristic, too long, or even too hard to sing or to remember the complicated lyrics. It did not become the official anthem until 1931 during President Herbert Hoover’s tenure and there were many outspoken critics of the choice at the time and since (“America the Beautiful” has always been a fan favorite). But enough about Key.

In recent years, and regardless of how one feels about it, it is clear that our national anthem has been at the center of controversy in terms of its meaning and our reactions to it. The anthem is, for some, a sacrosanct representation of America and to question it, to kneel during it, has become an act of such disrespect as to dominate national dialogue for years. But clearly questions remain regarding the idea of ownership and interpretation of the anthem. If indeed the anthem belongs to Americans and represents us as a unit, how do we come to a common consensus in regards to it? Do we even need to? If so, which Americans get to determine our anthem’s meaning and how we should respond to it? Who gets to embody Americanism and Americanness, and who gets to make the decision about how we display our patriotism or call our country to be its best self?

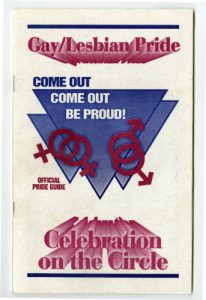

These questions lead to a much less publicized yet incredibly important event that occurred in Indianapolis during the Gay Pride celebration called “Celebration on the Circle,” held at Monument Circle on Saturday June 29, 1991. The gay community had been steadily growing and becoming more open in Indianapolis during the 1980s and early 1990s. Yet, it was still dangerous in many ways to live openly as a gay man or lesbian in the Midwest at the time. The vibrant gay bar scene and activism of the city were working on changing that by the early 1990s, but it was a long row to hoe, one that has not fully been completed across the state of Indiana.

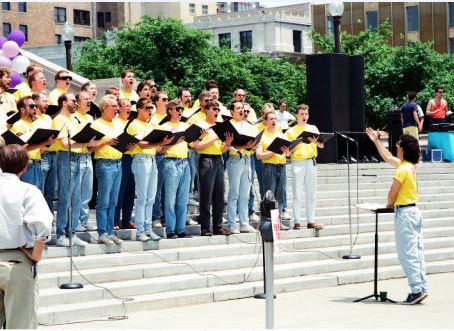

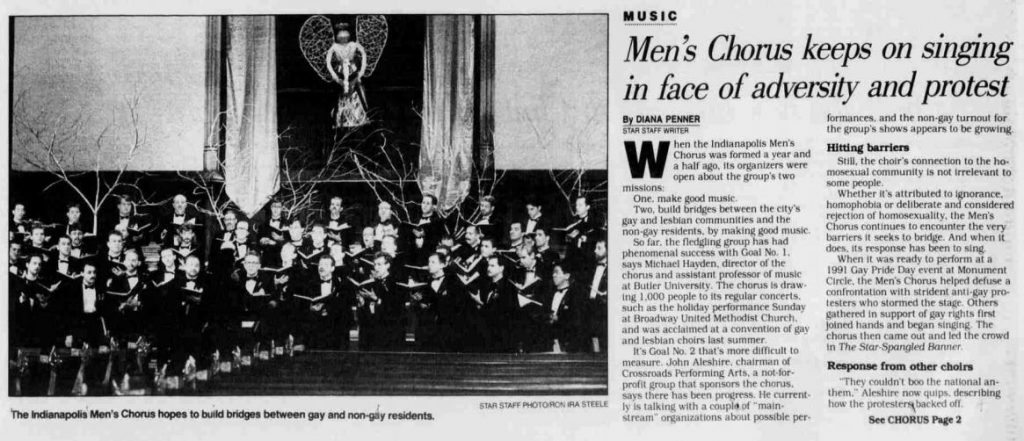

One important development, among many, of Indianapolis becoming a more welcoming community to LGBTQ folks was the founding and then performances of the Indianapolis Men’s Chorus. The Men’s Chorus was a gay men’s chorus founded by the non-profit Crossroads Performing Arts, Inc. Crossroads, whose steering committee was originally under the direction of Jim Luce, had been working since January 1990 to lay the groundwork for the Men’s Chorus with future goals to establish a Women’s Chorus and an instrumental group. Recruitment for the Men’s Chorus began in earnest by the end of March 1990, and the founding choral director, Michael Hayden, who was a music professor at Butler University, was hired in August 1990. Vocal auditions were held in late September and early October, and the Men’s Chorus began practicing in earnest on October 14. The group planned to formally debut in spring 1991, which they did at the historic Madame Walker Theater on Saturday June 8.

Crossroads’ mission was to “strengthen the spirit of pride within the gay/lesbian community, to build bridges of understanding with all people of Indiana, and to enable its audiences and the general public to perceive the gay/lesbian community and its members in a positive way.” It is not surprising then, that the newly formed Men’s Chorus was slated to perform at the Gay Pride celebration in Indianapolis in late June 1991, as part of their debut season. This was only the second Gay Pride event held at Monument Circle. Gay Pride events, hosted by various organizations such as Justice, Inc., had been held in the city in the past, but throughout the 1980s they were semi-closeted, meaning they were held in a hotel, bar or rented space that was not actually out in the public—it was deemed too dangerous to be that open. In 1988, however, the Pride celebration expanded with a festival held at the more public Indianapolis Sports Center. Approximately 175 people attended, and by the very next year, when the event moved to Westlake Park, the number had dramatically risen to 1,000.

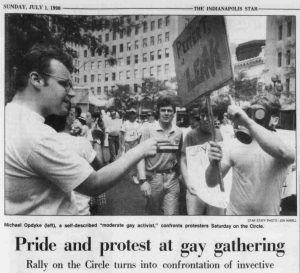

Yet, the gay community still had real cause for concern, particularly as they began celebrating more openly and in highly visible spaces. In 1990, the Pride festivities continued to expand and moved to Monument Circle for an event dubbed “Celebration on the Circle.” Virulent anti-gay protesters from a variety of Indianapolis churches wanted to intimidate them off the streets and back into the closets. According to the Indianapolis Star, approximately 100 protesters were on the scene, “many of whom wore gas masks and shouted insults as they walked around Monument Circle.” One anti-gay demonstrator explained why they were at the Circle: “We are all Christians who are here because we don’t approve of what these people are doing, trying to turn Indianapolis into another gay capital like San Francisco…I find it objectionable that they want to take their unholy, unacceptable lifestyle to the center of the city.” Indeed, the Indianapolis Star described the rally as “a confrontation with fundamentalist anger.”

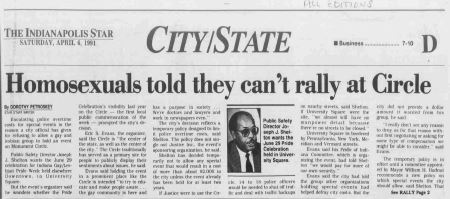

The climate was just as hostile or perhaps even more so for the second Pride event at the Circle. First off, in April 1991, city officials denied Justice, Inc. permission to hold the Pride rally at Monument Circle, and cited a temporary policy limiting “traffic disruption and police overtime as the reasons.” The Indiana Civil Liberties Union quickly planned to challenge the decision in court. Within weeks, Safety Director Joseph J. Shelton relented, stating, “The thing that really changed my mind about it is the fact that regardless of what we say or what we do, the outright appearance was that we were only imposing this restriction on this group… just because of the gay and lesbian organization.” After organizers were given the green light to host their event at the Circle, Pride attendees, including the Men’s Chorus singers, were still not exactly sure how they would be received by their own city and its citizens.

Hayden recalled having conversations with the singers about whether they wanted to perform at the Pride event and how the chorus wanted to be sensitive to its members’ differing levels of comfort. They were right to have concerns. Religious protesters, even angrier than at last year’s events, were in the mood for blood. And they arrived with baseball bats. Jim Luce wryly observed, “Because Jesus would have a baseball bat, right?”

Hayden and the Men’s Chorus, including Luce, walked into a hostile scene. As the 1991 Gay Pride event was getting ready to kick-off, approximately 40 protesters stormed the stage. Lt. Tom Bruno, of the Indianapolis Police Department’s traffic unit, described the protesters as being armed with “an attitude of confrontation.” As tensions mounted, John Aleshire, a spectator at Pride who later went on to chair the board of Crossroads Performing Arts, was unsettled by what was taking place before his eyes. He was both fearful of what was to come and felt helpless to stop it.

Right as the fundamentalist protesters and rally attendees including the Men’s Chorus, who had by then made their way onstage, seemed ready to clash, Michael Hayden, the chorus director, made a split-second decision. He somehow had the knowledge and foresight to choose the only song that could defuse the tension and make the bat-wielding Christians stop in their tracks. He looked at his men and said, “Sing the national anthem. Right now.” Pride attendees encircled the unwelcome protesters on the stage and assailed them with music. According to the Indianapolis Star, “it was a tense moment,” but as Aleshire recalled, “something magical happened.”

As the Men’s Chorus armed themselves with their voices, the protesters were taken aback. Luce described the scene: “It was fascinating to watch that group of people actively hating us while we were singing the National Anthem. I mean they actively hated us.” One onlooker later wrote, “Those who had wrapped their religion in Old Glory were hearing those ‘sissies’, ‘faggots’, and ‘moral degenerates’ demonstrating that the ugly protesters held no monopoly when it came to expressing their love of country.” And as Hayden queried, “What could they say? How could they protest America’s national anthem? There’s no way.”

Hayden in that moment understood what was at stake here: not only their right to be out in public as gay men and women, but their very Americanism. Hayden recalled thinking, “We’re Americans too. Shut up. We’re going to own this just like you. That flag represents us as well.” And the fundamentalists faced a choice as the notes of the “Star Spangled Banner” descended upon them: put their hands over their hearts as they had been taught that all loyal Americans should do when they hear our national anthem or charge full-force ahead at another group of patriotic Americans, nee Hoosiers, utilizing their right to celebrate in a public space. The protesters ultimately stopped and paid their respects to the anthem, and it was just enough pause to dull the escalating tension. In Hayden’s words, “We had sung them off the monument steps.”

After the protesters exited the stage, events were able to carry on without further disruption. No arrests were made and no violence occurred. Attendees were proud of how the Pride event transpired, but fear of being so openly exposed continued to permeate throughout the day.

Activists, particularly those with ties to the Men’s Chorus, remember with pride how they sang down the hatred using their own patriotism. Hayden described the Men’s Chorus singers as being these relatively young “homegrown” men, Hoosiers in their 20s and 30s who were “from these great families from Indiana.” And after the situation was defused, they started cheering and hugging each other, and processing what they had just done. The following month, Hayden wrote to his chorus to reflect on their experiences: “Seeing a man carry a ball bat or standing on the steps with them shouting in our faces just trying to enlist us to violence … and then this mighty male instrument opening its mouth and singing these ‘Christians’ right off the steps! Goliath has never seen a stronger David. I have never felt so proud to be gay, a musician, and what we know to be a true Christian in my entire life.”

Decades later, Hayden could still recall the emotions, power, and importance of what transpired that summer day. He reminisced, “We all felt it, and we knew we had done that with our voices and our national anthem.” Aleshire confirmed these feelings, “It proved to me, once again, that music is one of the most powerful forces to bring down walls and build bridges in their stead.”

Sources Used:

Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: An American Slave, Written by Himself, Edited with an Introduction by David W. Blight, (Bedford St. Martin’s, 2002).

Norman Gelb, “Francis Scott Key, the Reluctant Patriot,” Smithsonian Magazine, September 2004, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/francis-scott-key-the-reluctant-patriot-180937178/, Accessed 3 January 2019.

Michael Hayden, Interviews by author, September 10, 11, 19, 2018, October 1, 2018, November 12, 2018, In possession of author.

Ruth Holladay, “A gay chorus? In Indy? Planners say it’s about time,” Indianapolis Star. Wednesday June 20, 1990.

Tim Lucas, “Career Changes are his specialty,” Indianapolis Star, Sunday June 21, 1992.

Mary Carole McCauley, “’Star-Spangled Banner’ writer had complex record on race,” The Baltimore Sun, September 13, 2017, https://www.baltimoresun.com/entertainment/arts/bs-ae-key-legacy-20140726-story.html.

Kevin Morgan, “Pride and protest at gay gathering,” Indianapolis Star, Sunday July 1, 1990.

“Indianapolis’ LGBT History,” No Limits podcast, June 7, 2018, https://www.wfyi.org/programs/no-limits/radio/Indianapolis-LGBT-History.

Indianapolis Men’s Chorus/Crossroads Performing Arts, Inc. Records, ca. 1989-1995, 2005. William Henry Smith Memorial Library, Indiana Historical Society, Indianapolis, Indiana.

“3,000 gays expected for event,” Indianapolis Star, Friday June 29, 1990.

Kyle Niederpruem, “Gay bar patrons often crime targets,” Indianapolis Star, Sunday September 30, 1990.

Diana Penner, “Men’s Chorus keeps on singing in face of adversity and protest,” Indianapolis Star, Tuesday December 29, 1992.

Dorothy Petroskey, “Homosexuals told they can’t rally at Circle,” Indianapolis Star, Saturday April 6, 1991.

Jacqui Podzius, “Homosexuals show their pride at rally,” Indianapolis Star, Sunday June 30, 1991.

Don Sherfick, “A Salute to the Indychoruses Bridge-Builders,” https://indianaequality.typepad.com/indiana_equality_blog/2008/09/a-salute-to-the.html, Accessed 2 August 2018.

AJ Willingham, “The unexpected connection between slavery, NFL protests, and the national anthem,” August 22, 2017, https://www.cnn.com/2016/08/29/sport/colin-kaepernick-flag-protest-has-history-trnd/index.html.

Christopher Wilson, “Where’s the Debate on Francis Scott Key’s Slave-Holding Legacy?” Smithsonian.com, July 1, 2016, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/wheres-debate-francis-scott-keys-slave-holding-legacy-180959550/.

Indy Pride, “History of Pride,” https://indypride.org/about/history/, Accessed 15 January 2019.