For many former Indiana lawmakers, the legislative and technological world feels quite different from the one in which they began their political careers. Recently, The Wall Street Journal reported that statistically the U.S. is the only democratic nation in the world where social trust has seen a major decline, suggesting political polarization is the major driving force.[1] Luckily, history provides us with perspective in these contentious times, reminding us of an age when things were once different and that there is always hope for change.

According to former legislators of the Indiana General Assembly (IGA), politicians have generally collaborated well and operated in an atmosphere where, despite political disagreements, most worked congenially across party lines. This is not to say that political polarization is as tense as it appears at the federal level, but Indiana Legislative Oral History Initiative (ILOHI) interviews indicate that bipartisanship is harder in Indiana than it once was. As ILOHI’s oral historian, I found myself hearing over and over again from legislators who began their careers in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s that state politics have changed, that the current political climate is less collegial. This belief was echoed by former legislators of both major political parties.

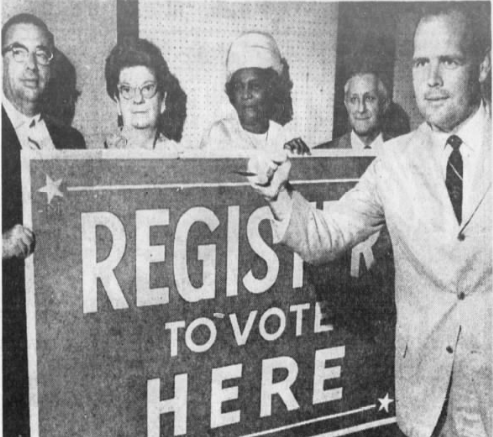

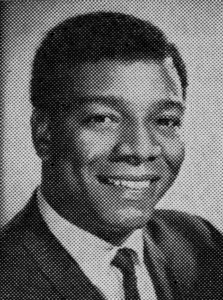

When asking former Republican legislators about their impressions of bipartisan cooperation during their service compared to today, I was given the following responses. Former Republican Rep. Ned Lamkin, who served in the House of Representatives from 1967 to 1982 and was crucial in creating Unigov legislation (which merged Marion County and the City of Indianapolis), stated: “ bipartisan groups would go to lunch together every day . . . so we had really good . . . collegial relationships with one another unlike it is today . . . we really did say ‘only 10% of this is political.’” Lamkin’s African American colleague, Representative Choice Edwards, served during the 1969 session and helped pass Unigov into law. In an ILOHI interview, Edwards recounted his experience in the IGA, saying “So it went from very serious kinds of things to jovial . . . you know I believe to quote the philosopher Mencius if you ain’t laughing you ain’t living. So, I believe in . . . trying to ease tensions with laughter.”

Edwards’ predecessor, Republican Van Smith, who served in the Indiana House of Representatives in 1961 and was chairman of former Vice President Mike Pence’s successful 2012 gubernatorial campaign, echoed these same thoughts. He reflected:

There’s not deep bipartisan political respect that there once was. I don’t know I would have as much enjoyment in the legislature as I had before. I don’t know if I would have as much fun running for public office as I had before. There is this tendency to really build extreme vitriol positions against personalities, rather than have a good discussion of issues. It saddens me, because it’s a magnification in both parties, it’s a magnification of the bitterness, the attractiveness of being bitter. . . I am a staunch Christian and it just ain’t good.

Former Democratic legislators, like Rep. Charlie Brown, who served from 1982 to 2018, too observed increasing political polarization. Brown contended:

It’s just over the last six years, that what you see at the federal level was at the local level here. It used to be that we’d fuss and fight on the floor or in committee, but then go out and have a drink or have dinner together. That changed drastically over the last six or eight years. It was a total separation and isolation of the parties as it is at the federal level. I don’t know what brought that on. We just do not have that camaraderie any longer.

Democrat Lindel Hume, who served in the House of Representatives from 1974 to 1982 and the Senate from 1982 to 2014, echoed this, stating

It’s a tale of two legislatures . . . Whether you were Democrat or Republican you had friends on both sides of the aisle and you would kid around together . . . A much better relationship across party lines and one of the reasons I decided to retire from the legislature was that it just wasn’t the same.

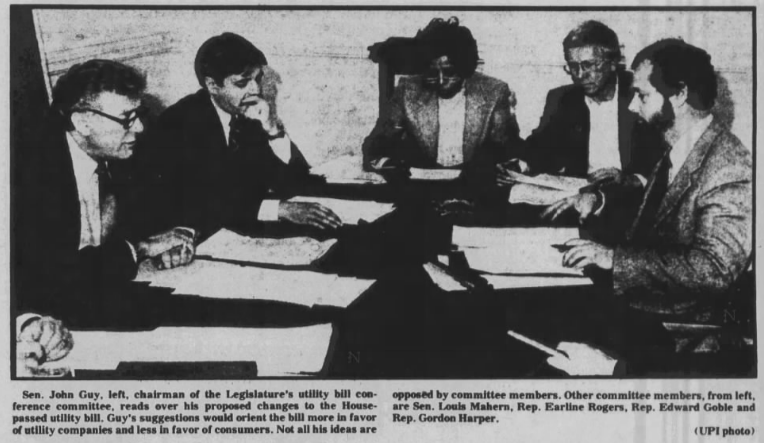

African American teacher and Democratic legislator Earline Rogers served in the House from 1983 to 1990 and Senate from 1990 to 2016. She noted that despite differing races or parties, her statehouse colleagues respected and related to one another, adding that the public probably wouldn’t “recognize the camaraderie that’s there.” She also recalled that while caring for loved ones diagnosed with cancer, she and Republican colleague Tom Wyss, “went through something together. . . there’s a bond that political parties just can’t break up.”

While the legislators agreed that polarization had intensified, most did not attribute it to a specific source. One major factor exists today that did not in the early careers of former legislators: the internet. The Pew Research Center reported in early 2020 the results of a survey regarding how trustworthy Democrats and Republicans found 30 different news sources. The results found that Democrats trusted 22 of the sources and Republicans distrusted 20 of the sources, showing a deep divide.[2] The Wall Street Journal noted a few months back that mathematicians studying the role of social media in political polarization are seeing a disturbing trend, where social media sites appear designed to highlight the most contentious and extreme political posts.[3]

According to Facing History & Ourselves, online platforms “use algorithms to expose viewers to increasingly extreme content, which can lead them to fringe political views without their realizing it. . . . Spending time in a political echo-chamber can make it easier for negative feelings toward members of the other political party to develop.”[4] Information has become inherently political and it is harder than ever to discuss it, because so many have come to only trust information that fulfills their political biases. As a result, it is like throwing gasoline on a fire by reinforcing the idea that the other “side” is too extreme or untrustworthy to even interact with. In addition to “media bubbles,” Facing History cites “in-group bias,” or tribalism, and changing election policies like campaign finance reform and gerrymandering for increasing political polarization.

The 2021 session indicated that the party divide among Indiana legislators isn’t likely to narrow any time soon, given the recent tension in the Assembly over a proposed bill regarding a South Bend school district. When Democrats belonging to the Black Legislative Caucus expressed concerns that the bill would lead to racial segregation in South Bend, it was reported that a group of white Republican legislators booed and heckled them.[5] The conflict moved from the House floor to outside the chambers, and there, according to WFYI, a white male lawmaker had a confrontation with a black female legislator.[6] Democrats called for implicit bias training after the incident. While some legislators pushed back against this proposal, lawmakers on both sides of the aisle agreed that the conflict exposed serious issues in the IGA.

Perhaps, if there is one thing we can learn from former legislators, it is that things don’t have to be this way, that political echo chambers can be dismantled. The Association of Retired Members of the Indiana General Assembly, a bipartisan group founded in 2016, is hoping to restore civility and bipartisanship among legislators. An Indy Star op-ed noted the group is “joined in fellowship of our common legislative and political experiences as well as our respect for the legislative process.”[7] Every two years, it awards legislators who demonstrate courtesy and respect for other members, are willing to find common ground, demonstrate self-discipline, and appreciate the rights of others. The op-ed’s author stated, and ILOHI interviewees confirmed, “Legislators are human and can be passionate. They can also be civil and work together for the good of our state.”

Sources:

[1] Kevin Vallier, “Why Are Americans So Distrustful of Each Other?,” The Wall Street Journal, accessed WSJ.com.

[2] Mark Jurkowitz, Amy Mitchell, Elisa Shearer and Mason Walker, “U.S. Media Polarization and the 2020 Election: A Nation Divided,” accessed Pew Research Center.

[3] Christopher Mims, “Why Social Media Is So Good At Polarizing Us,” The Wall Street Journal, accessed Wall Street Journal.

[4] “Explainer: Political Polarization in the United States,” accessed Facing History & Ourselves.

[5] Brandon Smith, “Tensions Flare as Some Republicans Boo, Heckle Black Democrats on House Floor,” WBAA, February 19, 2021, accessed wbaa.org.

[6] Brandon Smith, “‘Nothing Was Normal’ About 2021 Legislative Session Amid COVID-19 Pandemic,” WFYI, April 26, 2021, accessed wfyi.org.

[7] Op-Ed, “Bipartisanship Group of Retired Indiana Lawmakers Encourages Civility,” Indianapolis Star, May 2, 2021, accessed IndyStar.com.