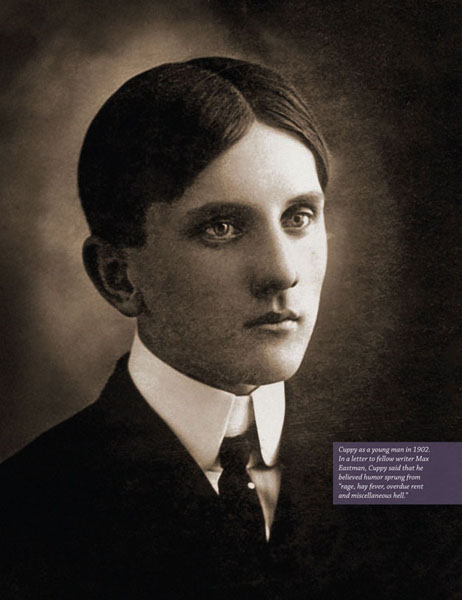

Humorist Will Cuppy’s witticisms tended toward, as his biographer Wes Gehring put it, “dark comedy that flirts with nihilism.” Cuppy’s The Decline and Fall of Practically Everybody, published posthumously in 1950, spent four months on the New York Times best-seller list and enjoyed eighteen reprints in hardback. Decline and Fall typified Cuppy’s life’s work, which satirized human nature and utilized footnotes to great comedic effect. He spent sixteen years researching the historic figures featured in Decline and Fall, but, after years of battling depression, passed away before its publication.

The Auburn, Indiana native spent a lot of time on his grandmother’s South Whitley farm. There, he developed a love of animals and a curiosity about life. According to an oft-cited anecdote, Cuppy found himself wondering if fish think—and no one he knew was curious enough to similarly wonder or care if indeed fish do think. In search of more inquisitive conversationalists, Cuppy moved out of Indiana as soon as he could. Upon graduation from Auburn High School, Cuppy departed for the University of Chicago where he would spend the next twelve years taking a wide array of courses. He completed his B.A. in philosophy and planned to get his Ph.D. in Elizabethan literature.

While at university, Cuppy worked for the school paper. As a result, the University of Chicago Press hired Cuppy to “create some old fraternity traditions for what was then a relatively new college” to give the school more of an old east coast university feel. This assignment evolved into Cuppy’s first book, Maroon Tales, published in 1910. Eventually, Cuppy’s college friend Burton Rascoe invited him out to New York City, where Rascoe was an editor and literary critic for the New York Tribune. After agreeing to move to New York City, Cuppy decided to get his M.A. in literature and leave the University of Chicago rather than complete his Ph.D. He was ready to move on.

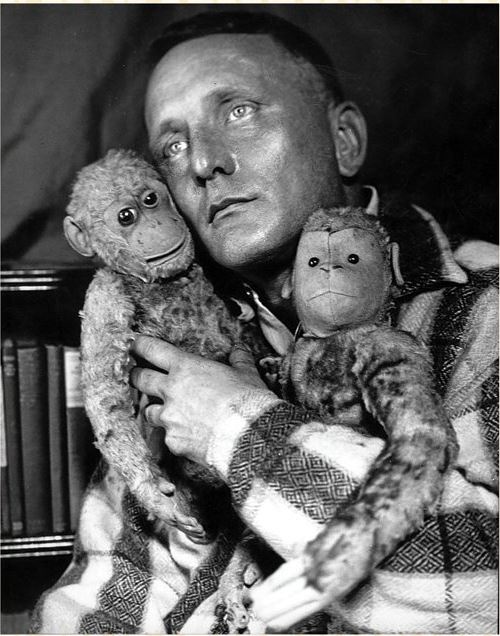

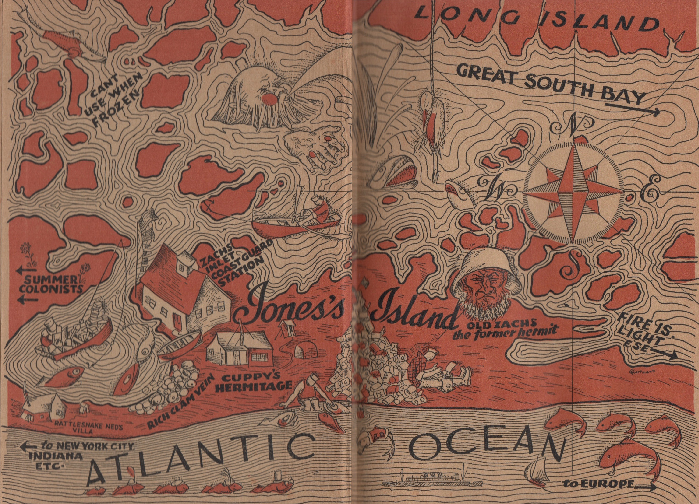

In 1921, Cuppy moved into a tarpaper and tin shack on Jones’ Island in New York. Suffering from hypersensitivity to sound, Cuppy wished to escape the noise of the city. He lived on the island year-round for eight years, with occasional visits to the city for supplies. The men of the Coast Guard station a few hundred feet down the beach befriended him and shared food, as well as fixed his typewriter. Cuppy called his beach home Tottering-on-the-Brink, giving insight into his mental health. But despite his seclusion, Cuppy’s career progressed. By 1922, he was writing occasionally for the New York Tribune, and in 1926 he joined the staff there as a book reviewer (by which time the Tribune had become the New York Herald Tribune).

Then, in 1929, Cuppy had to leave his shack because New York designated the area to become a state park, although he received permission to visit his hermitage for irregular vacations. Cuppy moved to an apartment in Greenwich Village, but even after he left his residence at Jones’ Island he would sometimes be referred to—and refer to himself—as a hermit because he continued to maintain an isolated lifestyle. Predictably, Cuppy found it difficult to stand the noise of the humming city. He tended to sleep during the day and work during the night to minimize his exposure to the cacophonous sounds. When it all got to be too much, Cuppy would blow on noisemaker as hard as he could out an open window.

Cuppy published a book about his experience living on Jones’ Island in 1929, How to Be a Hermit (Or A Bachelor Keeps House). The book was a best-seller—reprinted six times in six months—and put Cuppy on the map as a humorist and author. In traditional Cuppy fashion, he quipped “I hear there’s a movement among them [architects] to use my bungalow as a textbook example of what’s wrong with their business. The sooner the better—that will give the dome of St. Paul’s a rest.” And then there was this telling jest:

Coffee! With the first nip of the godlike brew I decide not to jump off the roof until things get worse—I’ll give them another week or so.

Cuppy followed up Hermit with How to Tell Your Friends from the Apes in 1931.

The 1930s were a busy time for Cuppy. In 1930, he tried to establish himself as a comic lecturer; however, after a brief stint of talks, it appeared the venture did not work out. A few years later Cuppy hosted a short-lived radio program on NBC called “Just Relax.” It proved too difficult to sustain a radio program with Cuppy’s singular brand of comedy and socially anxious tendencies—radio executives simply told him he wasn’t funny. Though his program didn’t last, Cuppy continued to appear in radio broadcasts sporadically through the years. He went on the radio to promote his next book, How to Become Extinct (1941).

Numerous reviews of mystery and crime novels had garnered Cuppy the distinction of being “America’s mystery story expert” as early as 1935. It was earned—in the course of his career Cuppy published around 4,000 book reviews. He secretly admitted that his heart wasn’t in it and he’d never particularly enjoyed the mystery and detective genre, but reviewing these books in his New York Herald Tribune column “Mystery and Adventure” was Cuppy’s steadiest income stream over the years. Nevertheless, in the 1940s Cuppy used his genre expertise to edit three anthologies of mystery and crime fiction. His freelance writing also picked up in this decade. National publications like McCall’s Magazine, The New Yorker, College Humor, For Men, and The Saturday Evening Post printed Cuppy’s essays that would later be compiled in his books, like How to Attract the Wombat (1949).

In a reflection that brings to mind Hoosier novelist Kurt Vonnegut Jr., Cuppy was fond of saying:

I’m billed as a humorist, but of course I’m a tragedian at heart.

One gets the sense from reading Cuppy’s material that he used humor as a coping mechanism. Quoting Cuppy, Gehring wrote that the dark humorist “believed humor sprang from ‘rage, hay fever, overdue rent, and miscellaneous hell.’” You could say that, like his humor, Cuppy’s life was tragic. Though he had long suffered from depression, multiple sources noted Cuppy’s declining health in mid-1949. Then, threatened with eviction from his Greenwich Village apartment and reeling from the end of a decades-long friendship, Cuppy followed through on decades of casual talk about self-harm. He died on September 19, 1949, due to suicide. He was buried in Auburn, Indiana’s Evergreen Cemetery.

After Cuppy died, his editor, Fred Feldkamp, took on the task of assembling Cuppy’s numerous notes into The Decline and Fall of Practically Everybody. Cuppy took his research seriously, and this is where Cuppy’s extensive education shined through. He would spend months researching a single short essay, reading everything he could find on the topic and amassing sometimes hundreds of notecards on each subject. Having worked on Decline and Fall for a whopping sixteen years before his death, Cuppy had collected many boxes of notecards filled with research. Decline and Fall was an immediate success when it was published in 1950. Locally, the Indianapolis News named it one of the best humor books of the year, and listed it as the top best-seller in Indianapolis in non-fiction for the year. In 1951, Feldkamp used more of Cuppy’s notes to edit and publish How to Get from January to December; it was the final publication in Cuppy’s name.

Cuppy’s style was characterized by a satirical take on nature and historical figures. Footnotes were his comedic specialty—they were such a successful trademark that he was sometimes hired to add his touch of footnote flair to the works of fellow humorists. In Decline and Fall there is one footnote in particular which is emblematic of Cuppy’s unique dark humor: “It’s easy to see the faults in people, I know; and it’s harder to see the good. Especially when the good isn’t there.” Before the publication of Decline and Fall, Cuppy was frequently asked why he always wrote about animals—when would he write about people? But, of course, he had been lampooning humanity all along.

Perhaps it makes sense, then, that in the last decade of his life, Cuppy befriended William Stieg, the man who would go on to create the character Shrek in his 1990 children’s book by the same name. A young cartoonist, Stieg was hired to illustrate How to Become Extinct and Decline and Fall. Cuppy and Stieg struck up an extensive correspondence, and Cuppy influenced Stieg’s style. The notion of a humorous curmudgeon living in isolation and drawn out into the world by both necessity and outgoing friends strikes a familiar chord that echoes in Shrek.

Cuppy was a famous humorist in his time, and the acclaim of his better-known comedy contemporaries, like P. G. Wodehouse and James Thurber, certainly helped to heighten his renown. When Decline and Fall came out, a reviewer for the New York Times insisted that “certain people, at least, thought [Cuppy] among the funniest men writing in English.” Beyond his work as a humorist, Cuppy’s career as a literary critic had been impactful; the managing editor of the Detroit Free Press wrote that he had “given up reading whodunits” after Cuppy’s death because he didn’t trust any other critic to guide his mystery selections. The sadly serious humorist is less widely known today, but his quips seem more relevant than ever.

Be sure to see Will Cuppy’s state historical marker at the site of his childhood home in Auburn after it is unveiled in August.

Further reading:

Wes D. Gehring, Will Cuppy, American Satirist: A Biography (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2013).

Norris W. Yates, “Will Cuppy: The Wise Fool as Pedant,” in The American Humorist: Conscience of the Twentieth Century (Ames: Iowa State University Press, 1964).

Al Castle, “Naturalist Humor in Will Cuppy’s How to Tell Your Friends from the Apes,” Studies in American Humor, 2, 3 (1984): 330-336.